Lebanon's Media Sectarianism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television

UC Santa Barbara Global Societies Journal Title The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13s698mx Journal Global Societies Journal, 1(1) Author Elouardaoui, Ouidyane Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television | 100 The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? By: Ouidyane Elouardaoui ABSTRACT Arab media has experienced a radical shift starting in the 1990s with the emergence of a wide range of private satellite TV channels. These new TV channels, such as MBC (Middle East Broadcasting Center) and Aljazeera have rapidly become the leading Arab channels in the realms of entertainment and news broadcasting. These transnational channels are believed by many scholars to have challenged the traditional approach of their government–owned counterparts. Alternatively, other scholars argue that despite the easy flow of capital and images in present Arab television, having access to trustworthy information still poses a challenge due to the governments’ grip on the production and distribution of visual media. This paper brings together these contrasting perspectives, arguing that despite the unifying role of satellite Arab TV channels, in which national challenges are cast as common regional worries, democratization and social development have suffered. One primary factor is the presence of relationships forged between television broadcasters with influential government figures nationally and regionally within the Arab world. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

Al-Jazeera Through Today

“The opinion, and the other opinion” Sustaining a Free Press in the Middle East Kahlil Byrd and Theresse Kawarabayashi MIT’s Media in Transition 3 May 2-4, 2003 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 2 BACKGROUND AND HISTORY .............................................................................. 3 The Emir and Qatar, ................................................................................................... 3 Al-Jazeera Through Today ......................................................................................... 5 Critics of Al-Jazeera ................................................................................................... 6 BUSINESS MODEL ..................................................................................................... 7 Value Proposition....................................................................................................... 7 Market Segment.......................................................................................................... 8 Cost Structure and Profit Potential............................................................................ 9 Competitive Strategy ................................................................................................ 11 THE GLOBALIZATION OF AL-JAZEERA.......................................................... 13 CHALLENGES AL-JAZEERA FACES IN SUSTAINING ITS SUCCESS ........ 15 AL-JAZEERA’S NEXT MOVES............................................................................. -

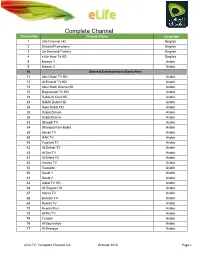

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Project of Statistical Data Collection on Film and Audiovisual Markets in 9 Mediterranean Countries

Film and audiovisual data collection project EU funded Programme FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL DATA COLLECTION PROJECT PROJECT TO COLLECT DATA ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL PROJECT OF STATISTICAL DATA COLLECTION ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL MARKETS IN 9 MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES Country profile: 3. LEBANON EUROMED AUDIOVISUAL III / CDSU in collaboration with the EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY Dr. Sahar Ali, Media Expert, CDSU Euromed Audiovisual III Under the supervision of Dr. André Lange, Head of the Department for Information on Markets and Financing, European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe) Tunis, 27th February 2013 Film and audiovisual data collection project Disclaimer “The present publication was produced with the assistance of the European Union. The capacity development support unit of Euromed Audiovisual III programme is alone responsible for the content of this publication which can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, or of the European Audiovisual Observatory or of the Council of Europe of which it is part.” The report is available on the website of the programme: www.euromedaudiovisual.net Film and audiovisual data collection project NATIONAL AUDIOVISUAL LANDSCAPE IN NINE PARTNER COUNTRIES LEBANON 1. BASIC DATA ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Institutions................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Landmarks ............................................................................................................................... -

1-U3753-WHS-Prog-Channel-FIBE

CHANNEL LISTING FIBE TV CURRENT AS OF JANUARY 15, 2015. $ 95/MO.1 CTV NEWS CHANNEL.............................501 NBC HD ........................................................ 1220 TSN1 ................................................................ 400 IN A BUNDLE CTV NEWS CHANNEL HD ..................1501 NTV - ST. JOHN’S ......................................212 TSN1 HD .......................................................1400 GOOD FROM 41 CTV TWO ......................................................202 O TSN RADIO 1050 .......................................977 A CTV TWO HD ............................................ 1202 OMNI.1 - TORONTO ................................206 TSN RADIO 1290 WINNIPEG ..............979 ABC - EAST ................................................... 221 E OMNI.1 HD - TORONTO ......................1206 TSN RADIO 990 MONTREAL ............ 980 ABC HD - EAST ..........................................1221 E! .........................................................................621 OMNI.2 - TORONTO ............................... 207 TSN3 ........................................................ VARIES ABORIGINAL VOICES RADIO ............946 E! HD ................................................................1621 OMNI.2 HD - TORONTO ......................1207 TSN3 HD ................................................ VARIES AMI-AUDIO ....................................................49 ÉSPACE MUSIQUE ................................... 975 ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE TSN4 ....................................................... -

Liste Des Canaux HD +

Liste des Canaux HD + - Enregistrement & programmation des enregistrements de chaînes (non-fonctionnel sur boîte Android / Smart Tv) - Le seul iptv offrant la fonction marche arrière sur vos canaux préférés - Vidéo sur demande – Films – Séries – Spectacle – Documentaire (Français, Anglais et Espagnole) Liste des canaux FRANÇAIS QUEBEC • TVA • TVA WEST • V TELE • TELE QUEBEC • LCN • MOI & CIE • CANAL D • RADIO CANADA • RADIO CANADA FREE • RDI • RDI FREE • CANAL SAVOIR • AMI TELE • UNIS TV • CANAL VIE • CASA • MUSIQUE PLUS • ZESTE • CANAL INVESTIGATION • CANAL D • ADDICK TV • SERIE + • Z TELE • VRAK • RDS • TVA SPORT • TVA SPORT 2 • RDS 2 • MAX • HISTORIA • PRISE 2 • SUPER ECRAN 1 • SUPER ECRAN 2 • SUPER ECRAN 3 • SUPER ECRAN 4 • ARTV • ICI EXPLORA • CINE-POP • EVASION • YOOPA • TELETOON *** AJOUT DE CANAUX A CHAQUE MOIS *** HORS QUÉBEC • France • TF1 • TFI LOCAL TIME -6 • M6 • M6 LOCAL TIME -6 • FRANCE 2 • FRANCE 3 • FRANCE 3 LOCAL TIME -6 • FRANCE 4 • FRANCE O • FRANCE 5 • ARTE • LCI • TV5 • TV5 MONDE • EURONEWS • BFM • BFM BUSINESS • FRANCE INFO • FRANCE 24 • CNEWS • HD1 • 6TER • W9 • W9 LOCAL TIME -6 • C8 • C8 LOCAL TIME -6 • 13 EIME RUE • PARIS PREMIERE • TEVA • COMEDIE • E! • NUMERO 23 • AB1 • TV BREIZH • NON STOP PEOPLE • NT1 • TCM CINEMA • TMC • CANAL + • CANAL + LOCAL TIME -6 • CANEL + CINEMA • CANAL + SERIES • CANAL + FAMILY • CANAL + DECALE • CINE + PREMIER • CINE + FRISSON • CINE + EMOTION • CINE + CLUB • CINE + CLASSIC • CINE FAMIZ • CINE FX • C STAR • CINE POLAR • OCS CITY • OCS MAX • OCS CHOC • OCS GEANT • GAME ONE • ACTION -

Voodoo Channel List

voodoo channel list ############################################################################## # English: 450-581 ############################################################################## # CBC HD Bravo USA CBS HF USA Space HD Global TV HD ABC HD USA AMC HD WPIX HD1 A/E USA LMN HD Fox HD USA Spike HD CNBC USA KTLA HD HIFI HD FX HD USA NBC HD CTV HD TNT HD E! HD SYFY HD USA Slice HD CP24 HD HBO HD Showcase HD Encore HD Showtime HD Start Movies HD Super CH 1 HD Super CH 2 HD TLC HD USA History HD USA History HD 2 National Geographic HD1 National Geographic USA Oasis HD Animal Planet HD USA Food Network HD USA HG TV USA Discovery HD USA Oasis Bloomberg HD USA CNN HD USA CNN Aljazeera English HLN Russia Today BBC News BBC 2 Bloomberg TV France 24 English Animal Planet Discovery Channel Discovery History Discovery Science Discovery History CBS Action CBS Drama CBS Reality Comedy Central Fashion TV Film4 Food Network FOX Investigation Discovery Lotus Movies MTV Music NASA TV Nat Geo Wild National Geographic Sky 2 Sky Living HYD Sky Movies Action Sky Movies Comedy Sky Movies Crime & Thriller Sky Movies Drama & Romance Sky Movies Family Sky Movies Premiere Sky Movies Sci-Fi & Horror Sky News Sky One SyFy Travel Channel True Movies 1, 2 UK Gold VH1 ############################################################################## # Sports: 600-643 ############################################################################## # TSN- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ESPN 2 USA NFL Network1 NBA TV Sportnet Ontario1 Sportnet World Sportnet 360 Tennis HD Sportsnet -

Satellite Television and Political Conflict in the Arab World

Satellite Television, the War on Terror and Political Conflict in the Arab World Lina Khatib In Alan Ingram and Klaus Dodds, (Eds.), Spaces of Security and Insecurity: Geographies of the War on Terror (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2009), pp. 205-220. The Arab world today is at a political crossroads. Continuing conflict in Iraq, tension in Lebanon, and intra-Palestinian rivalry threaten to destabilize the region. At the same time, foreign intervention in those conflicts shows no sign of decreasing, which is not surprising considering the international nature of politics in the Arab world. From the days of European mandates in the region, to the establishment of the state of Israel and subsequent Arab-Israeli wars, and on to Lebanese Civil War, the Palestinian intifada and the Gulf War, the Arab world has been host to a series of foreign interventions, both political and military. The so-called “war on terror” has only consolidated and intensified this intervention, so that the notion of geopolitics in the Middle East has come to take on a global, rather than a regional, dimension. Over the last decade, satellite television has affirmed its place as the primary news medium in the region. The Gulf War was marked by the dominance of CNN, its images of smart weapons and precise bombs colonizing television screens worldwide. The establishment of al-Jazeera in 1996 was the Middle East’s first attempt at entering the world of 24-hour news channels. However, although al-Jazeera was a well-respected and relatively well-known channel in the Arab world at the time, it did not enjoy a primary position in people’s homes. -

Lebanon's Media Battle by Paul Cochrane

Lebanon’s media battle By Paul Cochrane September, 2008. On May 7, what was supposed to be a day of strikes to demand higher wages metamorphosed into eight days of fighting between the Hizbullah-led opposition, “March 8,” and the pro-government, “March 14” forces.i At the forefront of Lebanon’s bloodiest infighting since the civil war were the media, relaying the heated words of politicians that stoked the conflict while beaming out propaganda thick and fast. During the conflict Lebanon’s media became further entrenched in their sectarian and political camps, pan-Arab media did the same, and domestic media outlets came under direct attack.ii The Lebanese public, meanwhile, holed themselves up inside and watched events play out on television. After Ghassan Ghosn, the head of the General Confederation of Lebanese Workers, announced that the strike was cancelled, Hizbullah and its supporters shut down Beirut by blocking roads with piles of rubble, burning tires and overturned rubbish bins. The following day, Hizbullah military units moved into the west of the city and started taking over, engaging in street battles with members of Sunni politician Saad Hariri’s Future movement and affiliated parties. What changed a day of socio-economic concerns into political violence were demands Prime Minister Fouad Siniora’s government made in the days prior to the clashes. Walid Jumblatt, the pro-government Druze leader and head of the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP), had called for Hizbullah’s private phone network to be shut down, the removal of surveillance cameras Hizbullah had installed by runways at the airport, and for the head of airport security, a Shia by the name of Wafik Shoukair, to be replaced as he was alleged to be working for Hizbullah. -

Liste Des Chaînes TV Chaînes En Option Haute Définition Inclus Dans Et Service Replay

Chaînes incluses 4K Ultra Haute Définition Inclus dans Liste des chaînes TV Chaînes en option Haute définition Inclus dans et Service Replay TNT 80 Comédie+ 204 Ushuaïa TV 314 France 3 Haute Normandie 0 Mosaique 81 Clique TV 205 Histoire 315 France 3 Languedoc 1 TF1 82 Toonami 206 Toute l'Histoire 316 France 3 Limousin 2 France 2 84 MTV 207 Science & Vie TV 317 France 3 Lorraine 3 France 3 86 Non Stop People 208 Animaux 318 France 3 Midi Pyrénées 4 Canal+ 87 MCM 209 Trek 319 France 3 Nord Pas de Calais 5 France 5 88 J-One 211 Souvenirs From Earth 320 France 3 Île de France 6 M6 89 Game One +1 212 Ikono TV 321 France 3 Pays de Loire 7 Arte 90 Mangas 213 Museum 322 France 3 Picardie 8 C8 91 ES1 214 MyZen Nature 323 France 3 Poitou Charente 9 W9 92 Adult Swim 215 Travel Channel 324 France 3 Provence Alpes 10 TMC 94 Gong 216 Chasse et pêche 325 France 3 Rhône-Alpes 11 TFX 95 Gong Max 217 Seasons 326 NoA 12 NRJ 12 96 Ginx 218 Télésud 13 LCP AN / Public Sénat 97 Comedy Central 219 Tahiti Nui INFOS & NEWS 14 France 4 98 Vice TV 221 Connaissances du Monde 340 France 24 (français) 15 BFM TV 99 BET 341 France 24 (anglais) 16 CNews 100 Stingray Festival 4K STYLE DE VIE / PRATIQUE 342 France 24 (arabe) 17 CStar 102 ARTE HDR (selon offre souscrite) 230 La Chaîne Météo 343 LCP Assemblée Nationale 18 Gulli 231 01 Net 344 Public Sénat 20 TF1 Séries Films CINÉMA 232 Autoplus 345 Euronews 21 L’Équipe 106 Canal + Séries 234 Gourmand TV 346 Euronews International 22 6ter 107 Abctek 235 Astro Center TV 347 BFM Business 23 RMC Story 108 Disneytek 236 Demain.TV