The Distress of Jews in the Soviet Union in the Wake of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JBC Book Clubs Discussion Guide Created in Partnership with Picador Jewishbookcouncil.Org

JBC Book Clubs Discussion Guide Created in partnership with Picador Jewishbookcouncil.org Jewish Book Council Contents: 20th Century Russia: In Brief 3 A Glossary of Cultural References 7 JBC Book Clubs Discussion Questions 16 Recipes Inspired by The Yid 20 Articles of Interest and Related Media 25 Paul Goldberg’s JBC Visiting Scribe Blog Posts 26 20th Century Russia: In Brief After the Russian Revolution of 1917 ended the Czar- Stalin and the Jews ist autocracy, Russia’s future was uncertain, with At the start of the Russian Revolution, though reli- many political groups vying for power and ideolog- gion and religiosity was considered outdated and su- ical dominance. This led to the Russian Civil War perstitious, anti-Semitism was officially renounced (1917-1922), which was primarily a war between the by Lenin’s soviet (council) and the Bolsheviks. Bolsheviks (the Red Army) and those who opposed During this time, the State sanctioned institutions of them. The opposing White Army was a loose collec- Yiddish culture, like GOSET, as a way of connecting tion of Russian political groups and foreign nations. with the people and bringing them into the Commu- Lenin’s Bolsheviks eventually defeated the Whites nist ideology. and established Soviet rule through all of Russia un- der the Russian Communist Party. Following Lenin’s Though Stalin was personally an anti-Semite who death in 1924, Joseph Stalin, the Secretary General of hated “yids” and considered the enemy Menshevik the RCP, assumed leadership of the Soviet Union. Party an organization of Jews (as opposed to the Bolsheviks which he considered to be Russian), as Under Stalin, the country underwent a period of late as 1931, he continued to condemn anti-Semitism. -

The Suppression of Jewish Culture by the Soviet Union's Emigration

\\server05\productn\B\BIN\23-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-JUL-05 11:26 A STRUGGLE TO PRESERVE ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE SUPPRESSION OF JEWISH CULTURE BY THE SOVIET UNION’S EMIGRATION POLICY BETWEEN 1945-1985 I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR .................. 159 R II. BEFORE THE BORDERS WERE CLOSED: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER STALIN (1945-1947) ......... 163 R III. CLOSING OF THE BORDER: CESSATION OF JEWISH EMIGRATION UNDER STALIN’S REGIME .................... 166 R IV. THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER KHRUSHCHEV AND BREZHNEV .................... 168 R V. CONCLUSION .............................................. 174 R I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR Despite undergoing numerous revisions, neither the Soviet Constitu- tion nor the Soviet Criminal Code ever adopted any laws or regulations that openly or implicitly permitted persecution of or discrimination against members of any minority group.1 On the surface, the laws were always structured to promote and protect equality of rights and status for more than one hundred different ethnic groups. Since November 15, 1917, a resolution issued by the Second All-Russia Congress of the Sovi- ets called for the “revoking of all and every national and national-relig- ious privilege and restriction.”2 The Congress also expressly recognized “the right of the peoples of Russia to free self-determination up to seces- sion and the formation of an independent state.” Identical resolutions were later adopted by each of the 15 Soviet Republics. Furthermore, Article 124 of the 1936 (Stalin-revised) Constitution stated that “[f]reedom of religious worship and freedom of anti-religious propaganda is recognized for all citizens.” 3 1 See generally W.E. -

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

ALEXIS PERI Department of History Boston University 226 Bay State Rd

ALEXIS PERI Department of History Boston University 226 Bay State Rd. Boston, MA 02215 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2019-current Associate Professor of History, Boston University Spring 2020 Visiting Associate Professor of History, University of California, Berkeley 2014-19 Assistant Professor of History, Boston University 2011-14 Assistant Professor of History, Middlebury College 2011 Lecturer, Saint Mary’s College of California ADDITIONAL EMPLOYMENT 2002-04 Administrative Assistant & Interview Auditor, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley EDUCATION 2011 Ph.D., History, University of California, Berkeley Awarded Distinction 2006 M.A., History, University of California, Berkeley 2002 B.A., History, Psychology, University of California, Berkeley Awarded Highest Achievement in General Scholarship PUBLICATIONS Books: The War Within: Diaries from the Siege of Leningrad. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017. Polish-Language Edition: Leningrad: Dzienniki z obezonego miasta. Siwek Grzegorz, trans. Krakow: Spoleczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak, 2019. Awards: Peri 1 of 14 Winner, Pushkin House Russian Book Prize, 2018 (“supports the best non-fiction writing in English on the Russian-speaking world”) http://www.pushkinhouse.org/2018-winner/ Winner, University of Southern California Book Prize in Literary and Cultural Studies, 2018 (“for an outstanding monograph published on Russia, Eastern Europe or Eurasia in the fields of literary and cultural studies”) https://www.aseees.org/programs/aseees-prizes/usc-book-prize-literary-and- -

Henryk Berlewi

HENRYK BERLEWI HENRYK © 2019 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2019 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F T HENRYK © O H C E M N 2019 A E R M R R I E L L B . C BERLEWI (1894-1967) HENRYK BERLEWI (1894-1967) Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait,1922. Gouache on paper. Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait, 1946. Pencil on paper. Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Design and production by Jolie Simpson Edited by Dr. Karen Kettering, Independent Scholar, Seattle, USA Copy edited by Lisa Berman Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2019 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2019 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Élément de la Mécano- Facture, 1923. Gouache on paper, 21 1/2 x 17 3/4” (55 x 45 cm) Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the staf of the Frick Collection Library and of the New York Public Library (Art and Architecture Division) for assisting with research for this publication. We would like to thank Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz and Julia Gutsch for assisting in editing the titles in Polish, French, and German languages, as well as Gershom Tzipris for transliteration of titles in Yiddish. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Marek Bartelik, author of Early Polish Modern Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) and Adrian Sudhalter, Research Curator of the Merrill C. -

Bul NKVD AJ.Indd

The NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 Anthology of the international conference Bratislava 14. – 16. 11. 2007 Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Nation´s Memory Institute BRATISLAVA 2008 Anthology was published with kind support of The International Visegrad Fund. Visegrad Fund NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Cen- tral and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 14 – 16 November, 2007, Bratislava, Slovakia Anthology of the international conference Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Published by Nation´s Memory Institute Nám. SNP 28 810 00 Bratislava Slovakia www.upn.gov.sk 1st edition English language correction Anitra N. Van Prooyen Slovak/Czech language correction Alexandra Grúňová, Katarína Szabová Translation Jana Krajňáková et al. Cover design Peter Rendek Lay-out, typeseting, printing by Vydavateľstvo Michala Vaška © Nation´s Memory Institute 2008 ISBN 978-80-89335-01-5 Nation´s Memory Institute 5 Contents DECLARATION on a conference NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 ..................................................................9 Conference opening František Mikloško ......................................................................................13 Jiří Liška ....................................................................................................... 15 Ivan A. Petranský ........................................................................................ -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

Polish Refugees in Iran During World War Ii

POLISH REFUGEES IN IRAN DURING WORLD WAR II On September 1, 1939, German forces invaded Poland and Forming the new Polish Army was not easy, however. Many defeated the Polish Army within weeks. Most of the westernmost Polish prisoners of war had died in the labor camps in the Soviet Polish territory was annexed directly to the Reich; the remainder Union. Many of those who survived were very weak from the of the areas conceded to Germany by the Molotov-Ribbentrop conditions in the camps and from malnourishment. Because Pact between the Soviet Union and Germany became the so- the Soviets were at war with Germany, there was little food called General Government (Generalgouvernement), administered or provisions available for the Polish Army. Thus, following by the German occupiers. In accordance with the pact’s secret the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941, the Soviets agreed protocols, the Soviet Union annexed most of eastern Poland after to evacuate part of the Polish formation to Iran. Non-military Poland’s defeat. As a result, millions of Poles fell under Soviet refugees, mostly women and children, were also transferred authority, either because they lived in areas the Soviets now across the Caspian Sea to Iran. occupied or because they had fled east to these areas as refugees from Nazi-occupied Poland. During this time, Iran was su∏ering economically. Following the invasion, the Soviets forbade the transfer of rice to the During their almost two-year-long occupation, Soviet authorities central and southern parts of the country, causing food scarcity, deported approximately 1.25 million Poles to many parts of the famine, and rising inflation. -

Caietele CNSAS, Nr. 2 (20) / 2017

Caietele CNSAS Revistă semestrială editată de Consiliul Naţional pentru Studierea Arhivelor Securităţii Minoritatea evreiască din România (I) Anul X, nr. 2 (20)/2017 Editura CNSAS Bucureşti 2018 Consiliul Naţional pentru Studierea Arhivelor Securităţii Bucureşti, str. Matei Basarab, nr. 55-57, sector 3 www.cnsas.ro Caietele CNSAS, anul X, nr. 2 (20)/2017 ISSN: 1844-6590 Consiliu ştiinţific: Dennis Deletant (University College London) Łukasz Kamiński (University of Wroclaw) Gail Kligman (University of California, Los Angeles) Dragoş Petrescu (University of Bucharest & CNSAS) Vladimir Tismăneanu (University of Maryland, College Park) Virgiliu-Leon Ţârău (Babeş-Bolyai University & CNSAS) Katherine Verdery (The City University of New York) Pavel Žáček (Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, Prague) Colegiul de redacţie: Elis Pleșa (coordonator număr tematic) Liviu Bejenaru Silviu B. Moldovan Liviu Ţăranu (editor) Coperta: Cătălin Mândrilă Machetare computerizată: Liviu Ţăranu Rezumate și corectură text în limba engleză: Gabriela Toma Responsabilitatea pentru conţinutul materialelor aparţine autorilor. Editura Consiliului Naţional pentru Studierea Arhivelor Securităţii e-mail: [email protected] CUPRINS I. Studii Natalia LAZĂR, Evreitate, antisemitism și aliya. Interviu cu Liviu Rotman, prof. univ. S.N.S.P.A. (1 decembrie 2017)………………………………7 Lya BENJAMIN, Ordinul B’nei Brith în România (I.O.B.B.). O scurtă istorie …………………………………………………………………............................25 Florin C. STAN, Aspecte privind emigrarea evreilor din U.R.S.S. -

Soviet Diplomacy and the Spanish Civil War *

SLIGHTLY REVISED 27.VII.2009 CHAPTER NINE CAUGHT IN A CLEFT STICK : SOVIET DIPLOMACY AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR * MICHAEL JABARA CARLEY The late British historian John Erickson wrote that the Spanish Civil War put the Soviet government into a cleft stick; caught between helping the Spanish Republic against a military, fascist uprising and alienating a new found, but milquetoast French ally. 1 The mutiny in Spain was directed against the recently elected centre-left coalition, the Popular Front, which included Spanish communists. It should have been normal for the Soviet Union to want to help workers and communists fighting against a right- wing, fascist mutiny. France too had just elected a Popular Front government, but the French coalition was fragile. Its most conservative element, the Radical party, was unwilling to get involved in Spain for fear of inflaming domestic political tensions or risking civil war. The British Conservative government also took a dim view of active involvement in the civil war and of Soviet intervention to support the Spanish Republicans, even if they were the legitimately elected, legal government. Most British Conservatives had a special aversion for the Soviet Union, and saw its involvement in Spain as a threat to spread communism into Western Europe. The Soviet government did not have the leisure to consider the Spanish problem outside the larger issue of its security in Europe. In January 1933 Adolf Hitler had taken power in Germany. The Soviet government immediately saw the danger even if the Soviet Union had maintained good or tolerable relations with the Weimar Republic during the 1920s. -

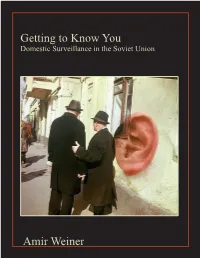

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime -

In the Underground Struggle Against Hitler

I , " Thursday, julY 15, 1943 . or liE J E WISH P O'B'T mHEA' JEWISH ~~~Aposm ________________________~~ ____________Thursday,~~~~~ July 15,1'943 1 Page Two --~~~~---------------------------- " in the role of a murderer in "M". It is told that during the early days EWSY OUT Film Folk of Adolf's advent, Lorre could have signed a U.F.A. contract, naming his N By HELEN ZIGMOND « OTES» own salary. He refused it, saying, The Oldest Anglo-Jewish Weekly in Western Canada In The Underground (Copyright, 1943, J.T,A.) al"lnlnlllllllll'tll"I'II"II'I"IUllllnl"llfl nl.IIIII.lllIlnl.III.I"II.1 Jews "There isn't room for two such (Issued weekly in the interests of Jewish Community Ilctivities in Winnipeg and Western Canada) ~urderers as Lorre and Hitler in By BORIS SMOLAR Hollywood-A, fighting ship named auxiliary screen, Germany!" Then he lit out of the Published every Thursday after Ensign D~niel Sied, U.S.N.} I * '" • country like a. bolt of "blitzen", , I was launched this week from Bos- One good turn deserves an- , ' by , " , , Against Hitler :I: * * , EMPIRE PRESS LTD. Struggle ton. Sied, son of a Columbia studio other: When Yehudi Menuhin, When the buzz or planes over- CEMENTING FRIENDSIDP - Unity between the Jews of Russia Printer and Publishers By S. ALMAZOV technician, was lost in his plane scheduled to go on the air for head stopped the shooting of an and the Jews in America is being successfully promoted by the Jewish , , BEN M. COHEN, BuSiness' Manager (Author of "The Underground War in Europe") during the first attack made by the the "Stage Door Canteen", dis- outdoor set, a sound-mixer grum delegation from Russia which is now in the United States ...