Int Evand) Court 5, Case 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hostage Case: Indictment

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Nuremberg Transcripts Collections 5-10-1947 Hostage Case: Indictment University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation University of North Dakota, "Hostage Case: Indictment" (1947). Nuremberg Transcripts. 4. https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts/4 This Court Document is brought to you for free and open access by the Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nuremberg Transcripts by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I. INDICTMENT, INCLUDING APPENDIX LISTING POSITIONS OF THE DEFENDANTS The United States of America, by the undersigned Telford Taylor,Chief of Counsel for War Crimes, duly appointed to represent saidGovernment in the prosecution of war criminals, charges the defendantsherein with the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity,as defined in Control Council Law No. 10, duly enacted by the AlliedControl Council on 20 December 1945. These crimes included murder,ill-treatment, and deportation to slave labor of prisoners of war andother members of the armed forces of nations at war with Germany, andof civilian populations of territories occupied by the German armedforces, plunder of public and private property, wanton destruction ofcities, towns, and villages, and other atrocities and offenses againstcivilian populations. The persons accused as guilty of these crimes and accordingly named as defendants in this case are: WILHELM LIST-Generalfeldmarschall (General of the Army) ; Commanderin Chief 12th Army, April-October 1941; Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Sϋdost(Armed Forces Commander Southeast), June-October 1941; Commander inChief Army Group A, July-September 1942. -

Indictment Transcript.Pdf

I. INDICTMENT, INCLUDING APPENDIX LISTING POSITIONS OF THE DEFENDANTS The United States of America, by the undersigned Telford Taylor, Chief of Counsel for War Crimes, duly appointed to represent said Government in the prosecution of war criminals, charges the defendants herein with the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity, as defined in Control Council Law No. 10, duly enacted by the Allied Control Council on 20 December 1945. These crimes included murder, ill-treatment, and deportation to slave labor of prisoners of war and other members of the armed forces of nations at war with Germany, and of civilian populations of territories occupied by the German armed forces, plunder of public and private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns, and villages, and other atrocities and offenses against civilian populations. The persons accused as guilty of these crimes and accordingly named as defendants in this case are: WILHELM LIST-Generalfeldmarschall (General of the Army) ; Commander in Chief 12th Army, April-October 1941; Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Sϋdost (Armed Forces Commander Southeast), June-October 1941; Commander in Chief Army Group A, July-September 1942. MAXIMILIAN VON WEICHs-Generalfeldmarschall (General of the Army) ; Commander in Chief 2d Army, April 1941-July 1942; Commander in Chief Army Group B, July 1942- February 1943; Commander in Chief Army Group F and Supreme Commander Southeast, August 1943-March 1945. LOTHAR RENDULIC-Generaloberst (General); Commander in Chief 2d Panzer Army, August 1943-June 1944; Commander in Chief 20th Mountain Army, July 1944-January 1945; Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Nord (Armed Forces Commander North), December 1944-January 1945; Commander in Chief Army Group North, January-March 1945; Commander in Chief Army Group Courland, March-April 1945; Commander in Chief Army Group South, April-May 1945. -

Miscellanea ,. .. by ROD Kollgaard Athena

Vo/3, No. 10 Numismatic Art of Antiquity OCTOBER 1989 $2.00 Symbols important Pegasos was Corinth's logo Miscellanea ,. .. by ROD Kollgaard Athena. The helmet which Athena The peoples of the ancient world wears is of ~ style that was developed • Outfoxed by the FAX were as proud of their heritage as we are at the city for a new type of heavy infantry, the hoplites, 'which evolved at In this world of high tech communications we sometimes marvel at the of OUTS. This is often reflected in their coinage, in particular on that of the Corinth, Argos, and Chalis c. 700 B.C., sophistication and capacity of the machines around us - the FAX machine Greeks. Before the Hellenistic Age. and soon after became popular being the latest wondennent. What we tend to forget is that people still when it became common for the coinage throughout Greece. control the machines. This fact recently became painfuUy clear to Mehrdad to portray living rulers, Greek cities The region of Carinthia lies at the Sadigh of Sadigh Gallery in ManhaUan. Mehrdad had a FAX machine carefully chose the symbols which they northeast comer of the Peloponnese near installed and widely publicized the new FAX telephone number, but the placed on their principle coinage. The the base of the Isthmus of Corinth machine had problems from the start. After a fru strating series of delays it city of Corinth. which was one of lhe which also connects with Attica. The was determined that the number ass igned was actually for an area some 30 wealthiest and most powerful of the main portion of the ancient city was miles away. -

Die Europastraße E40 Als Erinnerungspfad in Europa

Die Europastraße E40 als Erinnerungspfad in Europa Europejska trasa E40 - europejską drogą pamięci Європейська дорога Е40 - шлях пам'яті в Європі The highway E40 as path of remembrance in Europe 1 Flaggen auf der Titelseite: (die Jahreszahlen beschreiben den Zeitraum, in dem die abgebildeten Fahnen offiziell verwendet wurden.) Königreich Galizien und Lodomerien als österreichisches Kronland (1849 – 1918) Russisches Reich (1914 – 1917, nur für den privaten Gebrauch) Österreich-Ungarische Kriegsflagge (1915, nie offiziell eingeführt) Deutsches Reich (1871 - 1918) Ukrainische Volksrepublik (1917 - 1918) Ukrainischer Staat (1918) und Westukrainische Volksrepublik (1918 - 1919) Republik Polen (1919 - 1939) Ukrainische Sowjetrepublik (1937 - 1949) Deutsches Reich (1935 - 1945) Sowjetunion (Union der Sozialistischen Sowjetrepubliken) (bis 1991) Flagge der UPA - Ukrajinska Powstanska Armija (Ukrainische Aufstandsarmee) (40ger Jahre des 20.Jahrhunderts) Flagge der Polnischen Heimatarmee (während des Zweiten Weltkrieges) 2 Inhalt Seite Impressum 4 Quellenverzeichnis 5 „In Westgalizien erinnert man sich...“ 6 Unser Projekt 7 Nasz projekt 8 Наш проект 9 Our project 10 Der Projektraum 11 Vorgeschichte 12 polnische Adelsherrschaft in Galizien und Wolhynien 16 Kriegsvorbereitungen und Festungsbau 24 Der Erste Weltkrieg 27 Vom Ende des Ersten Weltkrieges, der Gründung neuer Nationalstaaten 58 bis zum Ende des polnisch-bolschewistischen Krieges Die „Zwischenkriegszeit“ vom Frieden von Riga (1921) 92 bis zum Beginn des Zweiten Weltkrieges (1939) Der Zweite -

Hubert Lanz Memoirs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8779r9w9 No online items Overview of the Hubert Lanz memoirs Processed by Hoover Institution Archives Staff. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2008 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Overview of the Hubert Lanz 89028 1 memoirs Overview of the Hubert Lanz memoirs Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Hoover Institution Archives Staff Date Completed: 2008 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from MARC record by David Sun. © 2008 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Hubert Lanz memoirs Dates: 1976 Collection Number: 89028 Creator: Lanz, Hubert, 1896-1982. Collection Size: 1 item (1 manuscript box) (0.4 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Relates to German mountain warfare operations in the Soviet Caucasus and in Yugoslavia and Greece during World War II. Photocopy. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: In German Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Hubert Lanz memoirs, [Box number], Hoover Institution Archives. -

Analecta VI Tomo 2.Pdf

FACULTAD DE MEDICINA Enrique Graue Wiechers Director Rosalinda Guevara Guzmán Secretaria General Francisco Cruz Ugarte Secretario Administrativo Jorge Avendaño Inestrillas Coordinador del Consejo Asesor de Publicaciones Carlos Viesca T. Jefe del Departamento de Historia y Filosofía de la Medicina SOCIETAS INTERNATIONALIS HISTORIAE MEDICINAE Athanasios Diamandopoulos Presidente Alain Touwaide Secretario General Gary Ferngren Secretario Adjunto Josef Honti, Giorgio Zanchin, Shifra Shuarts, Ricardo Cruz-Coke Vicepresidentes Alfredo Musajo-Somma, Cinthya Pitcock Tesoreros ANALECTA HISTORICO MEDICA VI (2) Guest Editors Massimo Pandolfi y Paolo Vanni Año VI, No. 2 2008 ER INT NAT S IO TA N IE A C L I O S S H E IS A T N O CI RIAE MEDI ANALECTA HISTORICO MEDICA Revista del Departamento de Historia y Filosofía de la Medicina de la Facultad de Medicina de la UNAM y la Sociedad Internacional de Historia de la Medicina Comité Editorial EDITORES Carlos Viesca T. y Jean-Pierre Tricot Patricia Aceves Xóchitl Martínez Barbosa COEDITORES Rolando Neri Vela Andrés Aranda y Diana Gasparon Mariblanca Ramos de Viesca Ana Cecilia Rodríguez de Romo CUIDADO DE LA EDICIÓN Martha Eugenia Rodríguez Pérez Carlos Viesca T. NTERN I Gabino SánchezAT Rosales DISEÑO, FORMACIÓN EDITORIAL S José SanfilippoI E IMPRESIÓN A O Gráfica, Creatividad y DiseñoT S.A. de C.V. Comité Editorial InternacionalN [email protected] A I Philippe Albou (Francia) L © Derechos reservadosC conforme a la ley Klaus Bergdolt (Alemania) DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y FILOSOFÍA German Berrios (UK) I DE LA MEDICINA DE LA FACULTA D DE O J. S. G. Blair (UK) S MEDICINA DE LA UNivERSIDAD NACIONAL Antonio Carreras Panchón (España) AUTÓNOMA DE MSÉXICO. -

UN Guerrilla Warfare Greece 1941-1945.PDF

/ 4 6 ^7-^- " C^-- £-kA F G$CFLEAVE&W/O.xTH ' NC 1& GUERRILLA AND COUNTERGUERRILLA ACCESSION NO--------- PO REGISTR.. - - WARFARE IN GREECE, 1941 - 1945 by Hugh H. Gardner OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF MILITARY HISTORY Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 1962 GUERRILLA AND COUNTERGUERRILLA WARFARE IN GREECE, 1941 - 1945 by Hugh H. Gardner OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF MILITARY HISTORY Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 1962 This manuscript has been prepared in the Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, for use by the Special Warfare School, Special Warfare Center, Fort Bragg, N.C. Guerrilla and Counterguerrilla Warfare in Greece, 19141 - 19h5 constitutes the first part of a projected volume to con- tain histories of a number of guerrilla movements. In order that material contained in this portion may be made available to the Special Warfare School without delay, the author's first draft is being released prior to being fully reviewed and edited. The manuscript cannot, therefore, be considered or accepted as an official publication of the Office of the Chief of Military History, iii GUERRILA AND COUNTERGUERRILLA WARFARE PART I - GREECE TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I INVASION AND RESISTANCE (1940 - 1942) . .. 1 Introduction . 1 The Geography . 2 The Economy . Ethnic and Political Background . $ Italy and Germany Attack . 6 Greece in Defeat . 9 Development of the Resistance Movement . 12 Appearance of Overt Resistance . l The Guerrilla Organizations . 17 ELAS . 18 EDES . 20 EKKA . ...... • . .. 22 Other Andarte Organizations . 22 Outside Influences on the Development of the Guerrilla Movement . 25 Guerrilla Leadership . -

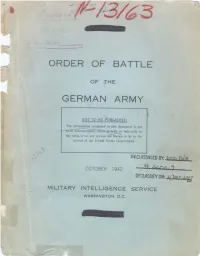

Usarmy Order of Battle GER Army Oct. 1942.Pdf

OF rTHE . , ' "... .. wti : :::. ' ;; : r ,; ,.:.. .. _ . - : , s "' ;:-:. :: :: .. , . >.. , . .,.. :K. .. ,. .. +. TABECLFCONENS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD iii - vi PART A - THE GERMAN HIGH COMMAND I INTRODUCTION....................... 2 II THE DEFENSE MINISTRY.................. 3 III ARMY GHQ........ 4 IV THE WAR DEPARTMENT....... 5 PART B - THE BASIC STRUCTURE I INTRODUCTION....................... 8 II THE MILITARY DISTRICT ORGANIZATION,- 8 III WAR DEPARTMENT CONTROL ............ 9 IV CONTROL OF MANPOWER . ........ 10 V CONTROL OF TRAINING.. .. ........ 11 VI SUMMARY.............. 11 VII DRAFT OF PERSON.NEL .... ..... ......... 12 VIII REPLACEMENT TRAINING UNITS: THE ORI- GINAL ALLOTMENENT.T. ...... .. 13 SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENTS... ........ 14 THE PRESENT ALLOTMENT..... 14 REPLACEMENT TRAINING UNITS IN OCCUPIED TERRITORY ..................... 15 XII MILITARY DISTRICTS (WEHRKREISE) . 17 XIII OCCUPIED COUNTRIES ........ 28 XIV THE THEATER OF WAR ........ "... 35 PART C - ORGANIZATIONS AND COMMANDERS I INTRODUCTION. ... ."....... 38 II ARMY GROUPS....... ....... .......... ....... 38 III ARMIES........... ................. 39 IV PANZER ARMIES .... 42 V INFANTRY CORPS.... ............. 43 VI PANZER CORPS...... "" .... .. :. .. 49 VII MOUNTAIN CORPS ... 51 VIII CORPS COMMANDS ... .......... :.. '52 IX PANZER DIVISIONS .. " . " " 55 X MOTORIZED DIVISIONS .. " 63 XI LIGHT DIVISIONS .... .............. : .. 68 XII MOUNTAIN DIVISIONS. " """ ," " """ 70 XII CAVALRY DIVISIONS.. .. ... ". ..... "s " .. 72 XIV INFANTRY DIVISIONS.. 73 XV "SICHERUNGS" -

M1035 Publication Title: Guide to Foreign Military Studies

Publication Number: M1035 Publication Title: Guide to Foreign Military Studies, 1945-54 Date Published: 1954 GUIDE TO FOREIGN MILITARY STUDIES, 1945-54 Preface This catalog and index is a guide to the manuscripts produced under the Foreign Military Studies Program of the Historical Division, United States Army, Europe, and of predecessor commands since 1945. Most of these manuscripts were prepared by former high-ranking officers of the German Armed Forces, writing under the sponsorship of their former adversaries. The program therefore represents an unusual degree of collaboration between officers of nations recently at war. The Foreign Military Studies Program actually began shortly after V-E Day, when Allied interrogators first questioned certain prominent German prisoners of war. Results were so encouraging that the program was expanded; written questions replaced oral interrogation, and later certain highly-placed German officers were asked to prepare a series of monographs. Originally the mission of the program was only to obtain information on enemy operations in the European Theater for use in the preparation of an official history of the U.S. Army in World War II. In 1946 the program was broadened to include the Mediterranean and Russian war theaters. Beginning in 1947 emphasis was placed on the preparation of operational studies for use by U.S. Army planning and training agencies and service schools. The result has been the collection of a large amount of useful information about the German Armed Forces, prepared by German military experts. While the primary aim of the program has remained unchanged, many of the more recent studies have analyzed the German experience with a view toward deriving useful lessons. -

United States Army European Command, Historical Division Typescript Studies, 1945-1954

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf696nb1jc No online items Register of the United States Army European Command, Historical Division Typescript Studies, 1945-1954 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1999, 2012 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. 66026 1 Register of the United States Army European Command, Historical Division Typescript Studies, 1945-1954 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1999, 2012 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: United States Army European Command, Historical Division Typescript Studies, Date (inclusive): 1945-1954 Collection number: 66026 Creator: United States. Army. European Command. Historical Division Collection Size: 60 manuscript boxes(25.2 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Relates to German military operations in Europe, on the Eastern Front, and in the Mediterranean Theater, during World War II. Studies prepared by former high-ranking German Army officers for the Foreign Military Studies Program of the Historical Division, U.S. Army, Europe. Language: English. Access Collection open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. -

Hostage Case: Arraignment

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Nuremberg Transcripts Collections 7-8-1947 Hostage Case: Arraignment University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation University of North Dakota, "Hostage Case: Arraignment" (1947). Nuremberg Transcripts. 3. https://commons.und.edu/nuremburg-transcripts/3 This Court Document is brought to you for free and open access by the Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nuremberg Transcripts by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 8 July-M-MJ-1-1-Love (Schaeffer) Court V, Case VII Official transcript of the American Military Tribunal in the United States of America against Wilhelm List, et al, defendants, sitting at Nurnberg[sic], Germany, on July 8, 1947, 0930, Justice Wennerstrum presiding. THE MARSHAL: The Honorable, the Judges of Military Tribunal 5. Military Tribunal 5 is now in session. God save the United States of America and this Honorable Tribunal. THE PRESIDENT: Military Tribunal 5 will come to order. The Tribunal will now proceed with the arraignment[sic] of the defendants in case number 7 pending before this Tribunal. The Secretary-General will call the roll of the defendants. The defendants will stand and answer their names when they are called. (The Secretary-General then clled[sic] the roll of the defendants. WILHEIM LIST, MAXIMILLIAN VON WEICHS, LOTHAR RENDULIC, WALTER KUNTZE, HERMANN FOERTSCH, FRANZ BOEHME, HELMUTH FEINY, HUBERT LANZ, ERNST DEHNER, ERNST VON LEYSER, WILHEIM SPEIDEL, KURT VON GEITNER. -

Battle for the Caucasus and «Edelweiss» Operation

Kesaonova Veronika Department of Economics, year 3 Battle for the Caucasus and «Edelweiss» Operation In August 1942, elite troops of the Wehrmacht mountain shooters advanced along the snowy slopes of Elbrus. Soldiers were dragging tools and building materials behind them in order to gain a foothold on the Caucasian ridge. The plan for the «Edelweiss» Operation was developed by Hitler in June 1942, when it became obvious to the Wehrmacht commander that the Blitzkrieg on the eastern front was dragging out, and they wouldn’t be able to win the war with the Soviet Union at a flash speed. The Führer decides: to bleed the Red Army, all the oil necessary for the work of Soviet armored vehicles and aircraft must be taken away from it. To do this, according to Hitler’s plan, Army Group "A" under the command of General Wilhelm List should have bypassed the Caucasian ridge from the west and, having captured Novorossiysk, moved to Tuapse - one of the oil regions of the Caucasus.At the same time, another army group " B" under the leadership of Fedor von Bock went to the eastern part of the Caucasus Range to take control of Grozny and Baku. In total, to capture the Soviet oil fields, 167 thousand soldiers, 15 thousand oil specialists and more than a thousand tanks were involved. The most unexpected blow of the Red Army was to be delivered by the mountain shooters of the Edelweiss division.This unit was to cross mountain passes unprotected by Soviet troops in the Elbrus region in order to hit the rear of the Red Army, trying to stop Army Group "A" in the west of the Caucasian ridge.