African Markets Revealed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pricing Guide 2021.Pdf

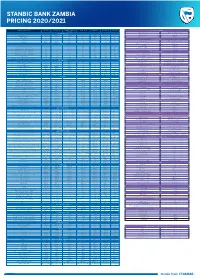

STANBIC BANK ZAMBIA PRICING 2020/2021 TYPE OF TRANSACTION PRIVATE EXECUTIVE ACHIEVER (EVERYDAY CORPORATE COMMERCIAL ENTERPRISE TAMANGA INVOICE DISCOUNTING BANKING) Arrangement Fee 2.5% Secured 5% unsecured ADMINISTRATION Interest rate LCY Customised Montly Management Fees ZMW 330 ZMW 110 ZMW 55 ZMW 200 ZMW 165 ZMW 150 ZMW 100 Interest rate FCY Customised Debit Activity Fees Free Free Free Free Free Free Free DISTRIBUTOR FINANCE Credit Activity Fees Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Arrangement fee 2.5% Secured 5% unsecured Bundle Pricing ZMW 385 ZMW 165 ZMW 87 N/A N/A N/A N/A DEPOSIT Management fee per quarter Customised Local cheque deposit at branch Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Rollover fee Customised Own Bank cheque within clearing area Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Interest rate (ZMW) Customised Own Bank cheque outside clearing area Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Interest rate (USD) Customised Agent Bank cheque within clearing area Free Free Free Free Free Free Free FOREIGN CURRENCY SERVICES Agent Bank cheque outside clearing area Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Purchase of Foreign Exchange Cash Deposit at Branch Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Foreign notes No charge Bulk Cash Deposit Foreign Currency ( Above $50,000) 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% Telegraphic Transfer/SWIFT (inward) US$20 flat WITHDRAWALS Drafts/Bills/Cheques 1.1% min US$40 plus VAT + Foreign charges At branch within K25,000 ATM limit Free Free ZMW 120 N/A N/A N/A N/A Drafts/Bills/Cheques 1.1% min US$40 plus VAT + Foreign charges Own ATM ZMW 9 ZMW 9 ZMW -

Stanbic Bank Zambia PMI™ Output Returns to Growth in May

News Release Embargoed until 1030 CAT (0830 UTC) 3 June 2021 Stanbic Bank Zambia PMI™ Output returns to growth in May Key findings PMI sa, >50 = improvement since previous month 60 First rise in activity for 27 months 55 Near-stabilisation of employment 50 45 Sharpest rise in purchase costs since December 40 2016 35 30 '15 '16 '17 '18 '19 '20 '21 Data were collected 12-24 May 2021 Sources: Stanbic Bank, IHS Markit. Output returned to growth in the Zambian private sector meant that firms were able to work through backlogs during May, one month after the same had been the case during May. A modest reduction in outstanding business for new orders. New business ticked back down slightly was recorded, ending a two-month sequence of in the latest survey period, but there were further signs accumulation. that overall business conditions are more conducive to Employment was broadly stable, falling only fractionally growth than has been the case for some time. As a result, and at the joint-slowest pace in the current 16-month firms continued to expand their purchasing activity and sequence of decline. kept their staffing levels broadly unchanged. Firms meanwhile increased their purchasing activity The headline figure derived from the survey is the for the second month running, leading to a further Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™). Readings above accumulation of inventories as suppliers' delivery times 50.0 signal an improvement in business conditions on improved for the first time in 16 months. Firms reported the previous month, while readings below 50.0 show a that competition among suppliers had been behind deterioration. -

LETSHEGO HOLDINGS LTD 2019 GROUP INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents

LETSHEGO HOLDINGS LTD 2019 GROUP INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents About this Report 4 Evolving the Integration of our Annual Reports 4 Scope 4 Materiality 4 A Note on Disclosures 4 Our Values 5 Our Business 6 Commentary from our Group Chairman 8 Group Chief Executive Review 12 2019 Milestones 17 Our Journey 18 Our Group Structure 20 Our Solutions 22 Our Footprint 23 How We Create Value 24 Financial Highlights 25 Non-Financial Highlights 28 Portfolio Review 32 Our Leadership 36 Group Board of Directors 38 Group Executive Committee 46 Country CEOs 48 The Board 50 Composition and Structure 52 Board Process and Outcomes 54 Composition of the Board Committees 58 Executive Management Committees 62 Attendance at Meetings 66 Remuneration Policy 67 Governance Enablers 70 Compliance with King IV 74 Stakeholder Engagement and Material Matter 78 Stakeholder Mapping Process 80 Our Key Stakeholders 81 Our Material Matter Identification and Management Process 83 Material Stakeholder Matters 84 2 INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Our People 88 Employee Value Proposition 90 Promoting Diversity 91 Employee Training and Development 92 Realising Financial Inclusion while Enhancing Financial Performance 94 Addressing the Needs of our Customers 96 Returning to Growth 98 Returning to Growth 100 Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Care 104 Measuring our Social Impact 106 Consolidated Annual Financial Statements 112 Group Corporate Information 114 Directors’ Report 115 Directors’ Responsibility Statement 117 Independent Auditor’s Report 118 Consolidated Annual -

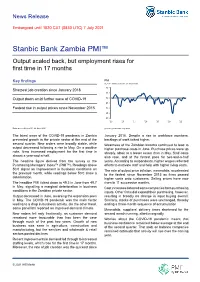

Stanbic Bank Zambia PMI™ Output Scaled Back, but Employment Rises for First Time in 17 Months

News Release Embargoed until 1030 CAT (0830 UTC) 7 July 2021 Stanbic Bank Zambia PMI™ Output scaled back, but employment rises for first time in 17 months Key findings PMI sa, >50 = improvement since previous month 60 Sharpest job creation since January 2018 55 Output down amid further wave of COVID-19 50 45 Fastest rise in output prices since November 2015 40 35 30 '15 '16 '17 '18 '19 '20 '21 Data were collected 11-24 June 2021 Sources: Stanbic Bank, IHS Markit. The latest wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Zambia January 2018. Despite a rise in workforce numbers, prevented growth in the private sector at the end of the backlogs of work ticked higher. second quarter. New orders were broadly stable, while Weakness of the Zambian kwacha continued to lead to output decreased following a rise in May. On a positive higher purchase costs in June. Purchase prices were up note, firms increased employment for the first time in sharply, albeit to a lesser extent than in May. Staff costs almost a year-and-a-half. also rose, and at the fastest pace for two-and-a-half The headline figure derived from the survey is the years. According to respondents, higher wages reflected Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™). Readings above efforts to motivate staff and help with higher living costs. 50.0 signal an improvement in business conditions on The rate of output price inflation, meanwhile, accelerated the previous month, while readings below 50.0 show a to the fastest since November 2015 as firms passed deterioration. -

Exim Bank EXIM JOURNEY – Key Milestones

Exim Bank EXIM JOURNEY – Key Milestones Second Strategic “Number One Bank in IFC- “Women overseas subsidiary in Customer Care” by the KPMG Entrepreneur DJIBOUTI Finance Africa Banking Survey, 2013 Programme” “Best Workplace Best Practice Environmental Practices for Training Award 2013 Introduced First and Development” in the 5.8% Stake in Visa Credit Card East Africa CSR Awards Crossed TZS 1 Trillion asset NMB mark Best Presented New Core Banking Introduced Financial System ‘Intellect’ 2013 First Master Statements NBAA Card Credit - 2008 and 2009 2011 Card in Times / IFC CB – CFC Tanzania Bank, Deutsche 2009 2014-15 Bank Loan From NORFUND 2012 Loan From – 2010 5th Largest bank in Tanzania IFC & 2004-07 PROPARCO Total Branches – 34 Stake in State of Art Tanzania Exim 2008 Total Asset – USD 640 Mn Mortgage Academy for Incorporated 2002 Refinance Training First Overseas Total Equity– USD 104 Mn First Branch in Company 2003 Subsidiary - Tanzania USD 15 Mn COMOROS Customers – 500,000 Introduced loan from First Debit - PROPARCO CB– PTA Bank “Sustainable Total Staff Strength - 750 Master , VISA 2001Introduced & HSBC Bank of the Platinum & Banking Started Year 2008 Partner with DEG -USD 20 Mn Credit Card in Software “MONEYGRAM” Award” by Loan 1997 TZ “FLEXICUBE” Money Transfer Financial “CB “– Correspondent Bank Services Times / IFC Presence Tanzania Comoros Djibouti Branches ATMs Extension Counters Tanzania 27 54 2 Comoros 5 7 0 Djibouti 2 1 0 34 62 2 • 10 Branches across • Established in • Established in 2010 Dar es Salaam 2007 • 2 Branches across Horn • 17 branches • Has 5 branches of Africa’s country. strategically located in connecting the • Strategically positioned upcountry business in the country with Indian Ocean opportunities such as; Islands good FDIs flows, entry / • Economy is mostly exit point for Ethiopia, import oriented logistics (ports) and transit (to and from Ethiopia) • Link between Africa and Asia / Europe The Vision and Strategy Retail Banking . -

ANNUAL INTEGRATED REPORT and FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2017 Stanbic Holdings Plc

ANNUAL INTEGRATED REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2017 STATEMENTS AND FINANCIAL REPORT INTEGRATED ANNUAL Stanbic Holdings Plc Holdings Stanbic Stanbic Holdings Plc Annual Integrated Report and Financial Statements 2017 Our report Our 2017 Annual Integrated Report is a demonstration of our commitment to, and strategies for, creating value for our customers, people, shareholders and community. This report aims to inform stakeholders about our financial and non-financial performance in 2017. This includes a look at how we create value over time and how our new strategy is structured to address the challenges, risks and opportunities Stanbic faces in a fast-changing world. We are committed to the principles of integrated reporting as they align with long-term value creation and the role we play as a bank in society, in moving Kenya forward. Our scope and content Unless otherwise stated, all information included in this report refers to the year ended 31st December 2017. It covers the operations of Stanbic Holdings Plc and the ways we are creating value for our stakeholders – in the context of our operating environment. All financial information presented, including the comparative periods, is in accordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) applicable to our operations and businesses. The non-financial sections of this report are guided by the International Integrated Reporting Council’s (IIRC) International Integrated Reporting Framework. We have determined the content of this report after extensive engagement with our customers, people, shareholders and community. Our materiality review We consider a material theme to be any matter that has the capacity to affect our shared value creation from the standpoint of the “Group” and its main stakeholders. -

Letshego Holdings Limited Annual Financial Statements for the Year

Letshego Holdings Limited Annual Financial Statements For the year ended 31 December 2018 CONTENTS ____________________________________________________________ Details Corporate information 3 Directors 4 Directors 6 7 Financial statements Statement of financial position 11 Statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 12 Statement of changes in equity 13 Statement of cash flows 14 Significant accounting policies 15 Notes to the financial statements 24 2 CORPORATE INFORMATION Letshego Holdings Limited is incorporated in the Republic of Botswana Registration number: Co. 98/442 Date of incorporation: 4 March 1998 A publicly listed commercial entity whose liability is limited by shares Company Secretary and Registered Office Lawrence Khupe (appointed 1 January 2018 and resigned 26 February 2019) Dumisani Ndebele (26 February 2019 and resigned 27 March 2019) Matshidiso Kimwaga (appointed 27 March 2019) Second Floor Letshego Place Plot 22 Khama Crescent Gaborone, Botswana Independent External Auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers Plot 50371 Fairground Office Park Gaborone, Botswana Transfer Secretaries PricewaterhouseCoopers (Pty) Limited Plot 50371 Fairground Office Park Gaborone, Botswana Attorneys and Legal Advisors Armstrongs Acacia House Plot 53438 Cnr Khama Crescent Extension and PG Matante Road Gaborone, Botswana Bankers Standard Chartered Bank Botswana Limited Barclays Bank Botswana Limited First National Bank Botswana Limited First National Bank of South Africa Limited Stanbic Bank Botswana Limited 3 DIRECTORS The Directors have pleasure in submitting to the Shareholders their report and the audited financial statements of Letshego Holdings Limited (the Company) for the year ended 31 December 2018. Nature of business The Company is engaged in investment in foreign and local operations involved in financial services. Stated capital Stated Capital of the Group at 31 December 2018 amounted to P862, 621,720 (31 December 2017: P849, 845,234). -

Southern African Development Community Payment System Integration Project

Southern African Development Community Payment System Integration Project SADC Integrated Regional Electronic Settlement System List of Participants as at April 2020 Number of Participants April 2020 Central Banks 7 Commercial 77 Total 84 Participants per country Country Participants Angola 1. Banco Angolano de Investimentos S.A. 2. Credisul-Banco de Credito do Sul S.A. 3. Banco de Negỏcios Internacional S.A. 4. Banco Prestígio SA Botswana 1. First National Bank of Botswana Pty Ltd 2. Stanbic Bank Botswana Limited 1 Country Participants Democratic Republic of Congo 1. Rawbank CD 1. Central Bank of Eswatini Eswatini 2. First National Bank of Eswatini 3. Nedbank Eswatini Limited 4. Standard Bank Eswatini Limited 5. Eswatini Development and Savings Bank Lesotho 1. Central Bank of Lesotho 2. First National Bank of Lesotho Limited 3. Lesotho Post Bank 4. Nedbank Lesotho Limited 5. Standard Lesotho Bank Madagascar No Participants yet 2 Country Participants 1. CDH Investment Bank Limited Malawi 2. Ecobank Malawi Limited 3. FDH Financial Holdings 4. First Merchant Bank Limited 5. National Bank of Malawi 6. NBS Bank Limited 7. New Finance Bank Malawi Limited 8. Reserve Bank of Malawi 9. Standard Bank Limited – Malawi 10. Opportunity Bank of Malawi Mauritius 1. Absa Bank Mauritius Limited 2. The Mauritius Commercial Bank Limited 3. Standard Bank Mauritius Limited 4. Standard Chartered Bank Mauritius Limited Mozambique 1. Barclays Bank Mocambique SA 2. FNB Mocambique SA 3. Banco Mais-Banco Mocambicano de Apoio aos Investimentos SA 4. Mozabanco SA 5. Standard Bank Mozambique SA 6. Banco Unico SA 3 Country Participants Namibia 1. Bank Windhoek Limited 2. -

African Markets Revealed

AFRICAN MARKETS REVEALED SEPTEMBER 2020 • Steven Barrow • Ferishka Bharuth • Mulalo Madula • Angeline Moseki • Fausio Mussa • Jibran Qureishi • Dmitry Shishkin • Gbolahan Taiwo www.standardbank.com/research 1 Standard Bank African Markets Revealed September 2020 Recovering, but not out of the woods • The worst of the pandemic will arguably be reflected in Q2:20 GDP growth outcomes. Of the countries in our coverage, we see only a handful of economies escaping recession in 2020. • Economic growth in Q2:20 contracted by 6.1% y/y, 3.3% y/y, and 3.2% y/y in Nigeria, Mozambique and Uganda respectively. The Ghanaian economy too contracted by 3.2% y/y in Q2:20, even worse than the 0.4% y/y contraction that we forecast for our bear scenario in the May edition of this publication. • The more diversified economies and those with large subsistence agriculture sectors could post mild, yet positive, growth in 2020. Most East African countries fall into this bracket. Egypt too might also avoid a technical recession this year. • However, Nigeria, Angola, Zambia and even Botswana, being overly reliant on just a few sectors to drive growth, will most likely contract this year. The only question is by how much? • Tourism-dependent economies will take a hit. We still don’t see any meaningful recovery in tourism until a global vaccine is at hand. The weakness in the tourism sector is mostly a BOP problem rather than a growth problem for many African countries. However, the service value chain that relies on a robust tourism sector too, will most likely weigh down growth in these economies. -

Stanbic Bank Kenya PMI™ Kenyan Economy Rebounds in May As Restrictions Ease

News Release Embargoed until 1030 EAT (0730 UTC) 4 June 2021 Stanbic Bank Kenya PMI™ Kenyan economy rebounds in May as restrictions ease Key findings PMI sa, >50 = improvement since previous month 65 Output and new business expand after severe 60 declines in April 55 50 Job numbers increase at quickest rate since 45 January 40 35 Margins squeezed despite slower rise in input 30 costs '14 '15 '16 '17 '18 '19 '20 '21 Sources: Stanbic Bank, IHS Markit. Data were collected 12-26 May 2021. Business conditions in the Kenyan private sector travel restrictions between counties. This loosening of recovered partially in May, after tightened measures measures also supported a sharp rise in new orders that on travel and curfew led to a steep contraction in April. was the quickest since October 2020. There was notable New business grew at the fastest rate in seven months, strength on the exports side, as orders from foreign while output and employment both rose to the strongest clients increased markedly. degrees since January. Price margins were squeezed Job creation returned in the latest survey period as a for the third month running as output charges rose at a result of a strong increase in workloads. This contributed slower rate than input prices, despite the latter increasing to a third consecutive fall in backlogs of work, albeit one at the softest pace since February. that was only fractional. The headline figure derived from the survey is the Input purchasing also moved into growth territory in May, Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI). Readings above although spare capacity gained from the previous month 50.0 signal an improvement in business conditions on helped suppliers to deliver inputs more quickly. -

Export-Import Bank of the United States

EXPORT-IMPORT BANK OF THE UNITED STATES ____________________________________ REPORT TO THE U.S. CONGRESS ON SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA FISCAL YEAR 2006 ________________________________________________________________________ FOR THE PERIOD OCTOBER 2005 THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2006 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary Page 2 II. Export-Import Bank Activities in Support of Sub-Saharan Africa Page 4 III. SAAC Recommendations to the Export-Import Bank Page 10 IV. Sub-Saharan Africa Activity Page 12 V. Appendices A. Export-Import Bank Success Stories: Sub-Saharan Africa Page 13 B. Biographies of 2004 Sub-Saharan Africa Advisory Committee Members Page 17 1 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY When reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 1997, the Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im Bank or the Bank) was mandated to increase financing of U.S. manufactured goods and services to sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) in a manner consistent with the reasonable assurance of repayment standard. Congress re-affirmed this mandate in the June 2002 reauthorization. As required by Section 7 of the current Export-Import Bank Reauthorization Act of 2001, this report outlines the Bank’s continuing efforts in Fiscal Year 2006 to satisfy the mandate. In FY 2006, Ex-Im Bank authorized 140 transactions totaling approximately $532 million in 23 sub-Saharan African countries. This includes for the first time the estimated amount of Bank’s working capital guarantee transactions that were made available to support U.S. exports to sub-Saharan Africa, which in FY 2006 totaled an estimated 31 transactions and approximately $90 million in authorizations. In the prior fiscal year, Ex-Im Bank authorized 115 transactions totaling $462 million in 20 countries, not including working capital activity. -

Stanbic Bank Zambia PMI™ Business Activity Decreases at End of Q1

News Release Embargoed until 1030 CAT (0830 UTC) 3 April 2019 Stanbic Bank Zambia PMI™ Business activity decreases at end of Q1 Key findings PMI sa, >50 = improvement since previous month 60 Output and new orders fall, following rises in February 55 Employment increases for first time in three months 50 Output price inflation at six-month low 45 40 '15 '16 '17 '18 '19 Sources: Stanbic Bank, IHS Markit. After showing signs of a pick-up in February, the Zambian output, with a lack of money preventing potential clients private sector suffered a renewed downturn in March. from committing to purchases. Business activity was scaled back in response to a drop With new orders down for the seventh time in eight in new orders, but firms did increase their staffing levels months, companies were able to work through outstanding during the month and were confident that output would business. Backlogs of work decreased sharply, and to the expand over the coming year. greatest extent since last October. The end of the first quarter of the year saw a lack of Despite falling workloads, employment at Zambian firms inflationary pressure in the private sector. Purchase ticked up in March. The marginal increase in staffing prices ticked down, while staff costs were unchanged. levels was the first in three months. Firms did raise their output prices, but at a modest pace that was slower than in February. There was little sign of any inflationary pressure in the private sector at the end of the first quarter. Purchase The headline figure derived from the survey is the prices decreased as falling demand for inputs led Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™).