Financial Service Provider Inventory Scan the FINANCING POTENTIAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issn 0856 – 8537 Directorate of Banking

ISSN 0856 – 8537 DIRECTORATE OF BANKING SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2017 21ST EDITION For any enquiries contact: Directorate of Banking Supervision Bank of Tanzania 2 Mirambo Street 11884 Dar Es Salaam TANZANIA Tel: +255 22 223 5482/3 Fax: +255 22 223 4194 Website: www.bot.go.tz TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................... Page LIST OF CHARTS ........................................................................................................................... iv ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................................................ v MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR ........................................................................................... vi FOREWORD BY THE DIRECTOR OF BANKING SUPERVISION .............................................. vii CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................................................. 1 OVERVIEW OF THE BANKING SECTOR .................................................................................... 1 1.1 Banking Institutions ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Branch Network ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Agent Banking ........................................................................................................................ -

Former DFCU Bank Bosses Charged Over Global Fund Scam

4 NEW VISION, Thursday, April 3, 2014 NATIONAL NEWS Former DFCU Bank bosses charged over Global Fund scam By Edward Anyoli Lule, while employed by Lule through manipulation of 300 sub-recipients and DFCU – a company in which Former Global Global Fund foreign exchange, individuals be audited further Two former managers of DFCU the Government had shares – falsely claiming that it was and that former health minister, Bank have been charged with directed the bank to convert Fund boss Dr. commission fees for soliciting Maj. Gen. Jim Muhwezi and abuse of office, costing the $2m Global Fund money into Global Fund business. his deputies; Mike Mukula Government sh479m. the local currency at an inflated Muhebwa was last Kantuntu, Lule and Kituuma and Alex Kamugisha, be Robert Katuntu, the former foreign exchange rate of Magala (a city lawyer, who is prosecuted. managing director of DFCU sh1,839 per dollar, which was week charged with summoned to appear in court This resulted into the and Godffrey Lule, the bank’s higher than the rate of sh1,815, on April 11) are jointly facing establishment of the anti- former head of treasury, were raising a difference of sh48m. causing financial the charges with Dr. Tiberius corruption division of the yesterday charged before the On another charge, Lule Muhebwa, the former Global High Court in December Anti-Corruption Court chief is accused of fraudulently loss of sh108m Fund project co-ordinator. 2008, which has convicted magistrate. They denied the directing the bank staff to Muhebwa has been charged two suspects; Teddy Cheeye charges and were granted cash convert $1m Global Fund with causing financial loss of the presidential adviser on bail of sh3m each. -

African Markets Revealed

AFRICAN MARKETS REVEALED SEPTEMBER 2020 • Steven Barrow • Ferishka Bharuth • Mulalo Madula • Angeline Moseki • Fausio Mussa • Jibran Qureishi • Dmitry Shishkin • Gbolahan Taiwo www.standardbank.com/research 1 Standard Bank African Markets Revealed September 2020 Recovering, but not out of the woods • The worst of the pandemic will arguably be reflected in Q2:20 GDP growth outcomes. Of the countries in our coverage, we see only a handful of economies escaping recession in 2020. • Economic growth in Q2:20 contracted by 6.1% y/y, 3.3% y/y, and 3.2% y/y in Nigeria, Mozambique and Uganda respectively. The Ghanaian economy too contracted by 3.2% y/y in Q2:20, even worse than the 0.4% y/y contraction that we forecast for our bear scenario in the May edition of this publication. • The more diversified economies and those with large subsistence agriculture sectors could post mild, yet positive, growth in 2020. Most East African countries fall into this bracket. Egypt too might also avoid a technical recession this year. • However, Nigeria, Angola, Zambia and even Botswana, being overly reliant on just a few sectors to drive growth, will most likely contract this year. The only question is by how much? • Tourism-dependent economies will take a hit. We still don’t see any meaningful recovery in tourism until a global vaccine is at hand. The weakness in the tourism sector is mostly a BOP problem rather than a growth problem for many African countries. However, the service value chain that relies on a robust tourism sector too, will most likely weigh down growth in these economies. -

Public Notice

PUBLIC NOTICE PROVISIONAL LIST OF TAXPAYERS EXEMPTED FROM 6% WITHHOLDING TAX FOR JANUARY – JUNE 2016 Section 119 (5) (f) (ii) of the Income Tax Act, Cap. 340 Uganda Revenue Authority hereby notifies the public that the list of taxpayers below, having satisfactorily fulfilled the requirements for this facility; will be exempted from 6% withholding tax for the period 1st January 2016 to 30th June 2016 PROVISIONAL WITHHOLDING TAX LIST FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY - JUNE 2016 SN TIN TAXPAYER NAME 1 1000380928 3R AGRO INDUSTRIES LIMITED 2 1000049868 3-Z FOUNDATION (U) LTD 3 1000024265 ABC CAPITAL BANK LIMITED 4 1000033223 AFRICA POLYSACK INDUSTRIES LIMITED 5 1000482081 AFRICAN FIELD EPIDEMIOLOGY NETWORK LTD 6 1000134272 AFRICAN FINE COFFEES ASSOCIATION 7 1000034607 AFRICAN QUEEN LIMITED 8 1000025846 APPLIANCE WORLD LIMITED 9 1000317043 BALYA STINT HARDWARE LIMITED 10 1000025663 BANK OF AFRICA - UGANDA LTD 11 1000025701 BANK OF BARODA (U) LIMITED 12 1000028435 BANK OF UGANDA 13 1000027755 BARCLAYS BANK (U) LTD. BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE CHILDRENS FOUNDATION 14 1000098610 UGANDA 15 1000026105 BIDCO UGANDA LIMITED 16 1000026050 BOLLORE AFRICA LOGISTICS UGANDA LIMITED 17 1000038228 BRITISH AIRWAYS 18 1000124037 BYANSI FISHERIES LTD 19 1000024548 CENTENARY RURAL DEVELOPMENT BANK LIMITED 20 1000024303 CENTURY BOTTLING CO. LTD. 21 1001017514 CHILDREN AT RISK ACTION NETWORK 22 1000691587 CHIMPANZEE SANCTUARY & WILDLIFE 23 1000028566 CITIBANK UGANDA LIMITED 24 1000026312 CITY OIL (U) LIMITED 25 1000024410 CIVICON LIMITED 26 1000023516 CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY -

List of Participants As of 30 April 2013

World Economic Forum on Africa List of Participants As of 30 April 2013 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 9-11 May 2012 Messumbe Stanly Paralegal The ABENG Law Firm Cameroon Abane Yilkal Abate Secretary-General ICT Association of Ethiopia Ethiopia Zein Abdalla Chief Executive Officer PepsiCo Europe Switzerland Amin Abdulkader Minister of Culture and Tourism of Ethiopia Rakeb Abebe Chief Executive Officer and Founder GAWT International Business Ethiopia Plc Olufemi Adeyemo Group Chief Financial Officer Oando Plc Nigeria Tedros Adhanom Minister of Health of Ethiopia Ghebreyesus Tedros Adhanom Minister of Health of Ethiopia Ghebreyesus Olusegun Aganga Minister of Industry, Trade and Investment of Nigeria Alfredo Agapiti President Tecnoservice Srl Italy Pranay Agarwal Principal Adviser, Corporate Finance MSP Steel & Power Ltd India and Strategy Vishal Agarwal Head, sub-Saharan Africa Deals and PwC Kenya Project Finance Pascal K. Agboyibor Managing Partner Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe France Manish Agrawal Director MSP Steel & Power Ltd India Deborah Ahenkorah Co-Founder and Executive Director The Golden Baobab Prize Ghana Halima Ahmed Political Activist and Candidate for The Youth Rehabilitation Somalia Member of Parliament Center Sofian Ahmed Minister of Finance and Economic Development of Ethiopia Dotun Ajayi Special Representative to the United African Business Roundtable Nigeria Nations and Regional Manager, West Africa Abi Ajayi Vice-President, Sub-Saharan Africa Bank of America Merrill Lynch United Kingdom Coverage and Origination Clare Akamanzi Chief Operating Officer Rwanda Development Board Rwanda (RDB) Satohiro Akimoto General Manager, Global Intelligence, Mitsubishi Corporation Japan Global Strategy and Business Development Adetokunbo Ayodele Head, Investor Relations Oando Plc Nigeria Akindele Kemi Lala Akindoju Facilitator Lufodo Academy of Nigeria Performing Arts (LAPA) World Economic Forum on Africa 1/23 Olanrewaju Akinola Editor This is Africa, Financial Times United Kingdom Vikram K. -

Bernard Bahemuka

Resume: Bernard Bahemuka Personal Information Application Title CHIEF CREDIT OFFICE First Name Bernard Middle Name N/A Last Name Bahemuka Email Address [email protected] Cell Nationality Uganda Gender Male Category Banking/ Finance Sub Category Private Banking Job Type Full-Time Highest Education University Total Experience 16 Year Date of Birth 27-03-1977 Work Phone +2560782366689 Home Phone N/A Date you can start 01-10-2020 Driving License Yes License No. 10143096/2/1 Searchable Yes I am Available Yes Address Address Address Hoima District City Hoima State N/A Country Uganda Institutes Institute Kampala International University City Kampala State N/A Country Uganda Address Kampala,Uganda Certificate Name Bachelors Degree in Business Administration Study Area Accounting & Management Institute Institute Of Teachers Education Kyambogo City Kampala State N/A Country Uganda Address Kampala, Uganda Certificate Name Diploma in Business Education Study Area Business Education Employers Employer Employer Encot Microfinance Limited Position Credit Manager Responsibilities Maintain and preserve Credit Operations policies , manage Credit Operations activities,Manage Credit Risk and grow the portfolio and clientele qualitatively Pay Upon Leaving 5,000,000 uganda Shillings Supervisor Chief Operating Officer From Date 01-10-2017 To Date N/A Leave Reason Carrier Growth City Kampala State N/A Country Uganda Phone N/A Address P.O.Box 389 Masindi Employer Employer Finance Trust Bank Position Branch Manager Responsibilities Over seeing general Branch -

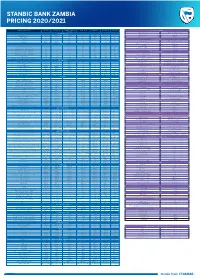

Pricing Guide 2021.Pdf

STANBIC BANK ZAMBIA PRICING 2020/2021 TYPE OF TRANSACTION PRIVATE EXECUTIVE ACHIEVER (EVERYDAY CORPORATE COMMERCIAL ENTERPRISE TAMANGA INVOICE DISCOUNTING BANKING) Arrangement Fee 2.5% Secured 5% unsecured ADMINISTRATION Interest rate LCY Customised Montly Management Fees ZMW 330 ZMW 110 ZMW 55 ZMW 200 ZMW 165 ZMW 150 ZMW 100 Interest rate FCY Customised Debit Activity Fees Free Free Free Free Free Free Free DISTRIBUTOR FINANCE Credit Activity Fees Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Arrangement fee 2.5% Secured 5% unsecured Bundle Pricing ZMW 385 ZMW 165 ZMW 87 N/A N/A N/A N/A DEPOSIT Management fee per quarter Customised Local cheque deposit at branch Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Rollover fee Customised Own Bank cheque within clearing area Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Interest rate (ZMW) Customised Own Bank cheque outside clearing area Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Interest rate (USD) Customised Agent Bank cheque within clearing area Free Free Free Free Free Free Free FOREIGN CURRENCY SERVICES Agent Bank cheque outside clearing area Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Purchase of Foreign Exchange Cash Deposit at Branch Free Free Free Free Free Free Free Foreign notes No charge Bulk Cash Deposit Foreign Currency ( Above $50,000) 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% Telegraphic Transfer/SWIFT (inward) US$20 flat WITHDRAWALS Drafts/Bills/Cheques 1.1% min US$40 plus VAT + Foreign charges At branch within K25,000 ATM limit Free Free ZMW 120 N/A N/A N/A N/A Drafts/Bills/Cheques 1.1% min US$40 plus VAT + Foreign charges Own ATM ZMW 9 ZMW 9 ZMW -

The World Bank for OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 59793-MW PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 18.1 MILLION Public Disclosure Authorized (US$28.2 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE THE REPUBLIC OF MALAWI FOR THE FINANCIAL SECTOR TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT (FSTAP) Public Disclosure Authorized February 28, 2011 Finance and Private Sector Development East and Southern Africa Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective January 31, 2011) Currency Unit = Malawi Kawacha (MK) US$1 = MK 150.77 US$1 = SDR 0.640229 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACH Automated Clearing House AfDB African Development Bank AFRITAC African Technical Assistance Center ATS Automated Transfer System BAM Bankers’ Association of Malawi BESTAP Business Environment Strengthening Technical Assistance Project BSD Banking Supervision Department CAS Country Assistance Strategy CEM Country Economic Memorandum CSC Credit and Savings Co-operatives CSD Central Securities Depository DEMAT Development of Malawi Trader’s Trust DFID UK Department of International Development EFT Electronic Funds Transfer FIMA The Financial Inclusion in Malawi FIRST Financial Sector Reform and Strengthening Initiative FMP Financial Management Plan FSAP Financial Sector -

UGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY ASSESSMENT August 2008

UGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY ASSESSMENT UGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY August 2008 August 2008 AMFIU House Plot 679, Wamala Rd, Najjanankumbi, Off Entebbe Rd AMFIU P. O. Box 26056 Kampala - Uganda Tel: +256 (0) 414 259176, Fax: +256 (0) 414 254420 ASSOCIATION OF MICROFINANCE JIREH GROUP Tel: +256 312 273126, INSTITUTIONS OF UGANDA Email: [email protected] : +256 712 965 315 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.amfiu.org.ug jirehgroupinvestmentsltd UGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY ASSESSMENTUGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY ASSESSMENT UGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY ASSESSMENT AUGUST 2008 1 UGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY ASSESSMENT UGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY ASSESSMENT FOREWARD Microfinance in Uganda has taken big strides since 1996 when stakeholders formally came together and since then it has been recognized internationally for its contribution to the economic and social development of the economically active poor in Uganda. However, due to the nascent level of the industry, there is limited and scattered information on what is taking place in the microfinance industry in Uganda. This Microfinance Industry Assessment study tries to compile information on various issues on the microfinance industry and gives an over-view of the general financial sector in Uganda, development and trends in the microfinance industry and issues on regulation of the sector. It provides a wealth of information and knowledge on what microfinance in Uganda is all about, how it fits into the overall financial sector and the role of various stakeholders in the industry. As a national Network for Ugandan microfinance practitioners and stakeholders, the Association of Microfinance Institutions of Uganda (AMFIU), has been involved in all the different stages of development of the MF industry. -

Stanbic Branches

UGANDA REVENUE AUTHORITY BANK ACCOUNTS FOR TAX COLLECTIONS BANK/ BRANCH STATION ACCOUNT NUMBER STANBIC BRANCHES STANBIC KABALE Kabale DT 014 0069420401 STANBIC KIHIHI Kihihi Ishasha 014 0072016701 STANBIC KISORO Kisoro DT 014 0067695501 STANBIC KITGUM Kitgum E&C 014 0013897701 STANBIC MOYO Moyo DT 014 0094774501 STANBIC NEBBI Nebbi Main 014 0093252701 STANBIC CUSTOMS Ntungamo Mirama 014 0059793301 STANBIC PAKWACH Pakwach CUE 014 0096061101 STANBIC GULU Gulu 014 00 87598001 STANBIC APAC Apac 014 0089064501 STANBIC LIRA Lira 014 0090947601 STANBIC KIBOGA Kiboga 014 0032789101 STANBIC MUBENDE Mubende 014 0029903401 STANBIC MITYANA Mityana 014 0028053701 STANBIC KYOTERA Kyotera 014 0064697901 STANBIC MUKONO Mukono 014 0023966401 STANBIC ARUA Arua DT 014 0091518701 STANBIC JINJA Jinja LTO 014 0034474801 STANBIC TORORO Tororo DT 014 0039797301 STANBIC NAKAWA 014 0014526801 STANBIC KAMPALA City ‐Corporate 014 00 62799201 Corporate‐Corporate 014 00 62799201 Lugogo‐Corporate 01400 62799201 STANBIC SOROTI Soroti 014 0050353901 STANBIC KASESE Kasese DT, Kasese CUE 014 00788089 01 STANBIC LUWERO Luwero(Kampala North) 014 00253024 01 STANBIC MOROTO Moroto 014 00486049 01 STANBIC WANDEGEYA Kampala North DT 014 00051699 01 STANBIC BUSIA Busia DT 014 00409365 01 STANBIC F/PORTAL F/Portal 014 00770127 01 STANBIC IGANGA Iganga 014 00 363457 01 STANBIC MALABA Malaba 014 00 420444 01 STANBIC MASAKA Masaka 014 00 824562 01 STANBIC MBALE Mbale DT 014 00 444509 01 STANBIC MBARARA Mbarara 014 00 537253 01 1 BANK/ BRANCH STATION ACCOUNT NUMBER STANBIC BUSHENYI -

NMB Bank – Bridging the Unbanked

Savings at the Frontier (SatF) A Mastercard Foundation partnership with Oxford Policy Management Project Briefing: NMB Bank – Bridging the Unbanked Introduction Tanzania’s NMB Bank Plc (NMB) is receiving support of up to $1,000,000 from SatF to bring formal financial services to some of Tanzania’s most excluDeD communities. NMB has partnered with CARE International anD will use the funDing to Digitise anD scale up the Bank’s current efforts to reach savings groups in peri-urban and rural parts of Tanzania. The project’s aim is that, By 2020, NMB will be clearly on track to making group anD group memBer outreach sustainaBle By aDDing 100,000 active rural anD peri-urban customers to its user base. These customers should Be clearly iDentifiaBle as memBers of savings groups, thereBy contriButing to the Bank’s longer term goal of signing up 28,000 savings groups with up to 600,000 memBers actively using NMB accounts. What difference will SatF’s support make? SatF’s support is helping NMB to link its existing group proDuct (Pamoja) with ChapChap, an entry- level inDividual moBile Banking proDuct. This is enabling NMB to keep transaction charges low anD tailor its offer to the neeDs of rural, unBankeD customers – particularly women. The Bank will also Be testing the efficiency gains from integrating Pamoja (the group proDuct) anD CARE’s Chomoka smartphone application for savings groups (SGs). Chomoka enables groups to Digitise their recorDs anD track the savings anD creDit histories of groups anD their memBers. The funDing will also enaBle NMB to Develop anD test a tailoreD creDit proDuct suiteD to the emerging neeDs, revealeD preferences of group members as well as their willingness anD ability to meet financial commitments. -

Invitation for Tenders

TANZANIA ELECTRIC SUPPLY COMPANY LTD Tender No. PA/001/2020-2021/HQ/G/185 For Supply of equipment and materials for construction of 400/220/132/132kV Chalinze substation Invitation for Tenders Date: 25/03/2021 1. The Government of the United Republic of Tanzania though Tanzania Electric Supply Company Limited (TANESCO) has funds for implementation of various strategic projects during the financial year 2020-2021. It is intended that part of the proceeds of the fund will be used to cover eligible payment under the contract for the Supply of equipment and materials for construction of 400/220/132/132kV Chalinze substation which is divided into the following scope: - - lot 1 for Supply of switchyard equipment - Lot 2 for Supply of Control, Protection and SCADA system equipment - Lot 3 for Supply of Steel Towers and Gantry structures 2. Each Lots has its own Tendering documents. Tenderer are allowed to quote for all Lots or Individual Lot. 3. The award will be made on Lot basis. 4. The Tanzania Electric Supply Company Limited (TANESCO) now invites tenders from eligible Manufacturers/Authorized dealers of Supply of equipment and materials for construction of 400/220/132/132kV Chalinze substation. 5. Tendering will be conducted through the International Competitive Tendering procedures specified in the Public Procurement Regulations, 2013 – Government Notice No. 446 as amended in 2016, and is open to all Tenderers as defined in the Regulations. 6. Interested eligible Tenderers may obtain further information from and inspect the Tendering document during office hours from 09:00 to 16:00 hours at the address given below; - The Secretary Tender Board, Tanzania Electric Supply Company Ltd, Street Address: Morogoro Road, Ubungo Area, Building/Plot No: Umeme Park Building, Floor/Room No: Ground Floor, Room No.