UGANDA MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY ASSESSMENT August 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TSBF Institute

TSBF Institute Annual Report 2002 VOLUME 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Project Description ………………………………………………………………………… 1 2. Logframe……………………………………………………………………………………. 2 3. Executive Summary Text………………….……………………………………………… 4 3.1 List of Staff….. ……………………………..………………………………………….. 4 3.2 List of Partners ……………………………..………….…………………..………….... 6 3.3 Financial Resources ……………………………………………………………………. 10 3.4 Main highlights of research progress in 2002..……………………………………. 13 3.5 Progress towards achieving output milestones of the project logframe 2002……. …… 19 4. Indicators Appendix A: List of Publications………………………………………………………….. 28 Appendix B: List of Students……………………………………………………………… 36 5. Output 1: Biophysical and socioeconomic constraints to integrated soil fertility management (ISFM) identified and knowledge on soil processes improved (1477 kb) Papers • BNF: A key input to integrated soil fertility management in the tropics. CIAT-TSBF Working Group on BNF-CP…………………………………………………………... 42 • Implications of local soil knowledge for integrated soil fertility management in Latin America. E.Barrios and M.T. Trejo. Geoderma, Special Issue on Ethnopedology (in press) ……………………………………………………… …………………………. 67 • Decomposition and nutrient release by green manures in a tropical hillside agroecosystem. J. G. Cobo, E. Barrios, D. C. L. Kass and R.J. Thomas . Plant and Soil 240: 331-342, 2002. ……………………………………………………………… 81 • Nitrogen mineralization and crop uptake from surface-applied leaves of green manure species on a tropical volcanic-ash soil. J.G. Cobo, E. Barrios, D.C.L. Kass and R.J. Thomas. Biol. Fert. Soils (2002) 36(2): 87-92………………………………. 96 • Plant growth, mycorrhizal association, nutrient uptake and phosphorus dynamics in a volcanic-ash soil in Colombia as affected by the establishment of Tithonia diversifolia. S. Phiri, I.M. Rao, E. Barrios, and B.R. Singh. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture (in press)……………………………………………………………………. -

Public Notice

PUBLIC NOTICE PROVISIONAL LIST OF TAXPAYERS EXEMPTED FROM 6% WITHHOLDING TAX FOR JANUARY – JUNE 2016 Section 119 (5) (f) (ii) of the Income Tax Act, Cap. 340 Uganda Revenue Authority hereby notifies the public that the list of taxpayers below, having satisfactorily fulfilled the requirements for this facility; will be exempted from 6% withholding tax for the period 1st January 2016 to 30th June 2016 PROVISIONAL WITHHOLDING TAX LIST FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY - JUNE 2016 SN TIN TAXPAYER NAME 1 1000380928 3R AGRO INDUSTRIES LIMITED 2 1000049868 3-Z FOUNDATION (U) LTD 3 1000024265 ABC CAPITAL BANK LIMITED 4 1000033223 AFRICA POLYSACK INDUSTRIES LIMITED 5 1000482081 AFRICAN FIELD EPIDEMIOLOGY NETWORK LTD 6 1000134272 AFRICAN FINE COFFEES ASSOCIATION 7 1000034607 AFRICAN QUEEN LIMITED 8 1000025846 APPLIANCE WORLD LIMITED 9 1000317043 BALYA STINT HARDWARE LIMITED 10 1000025663 BANK OF AFRICA - UGANDA LTD 11 1000025701 BANK OF BARODA (U) LIMITED 12 1000028435 BANK OF UGANDA 13 1000027755 BARCLAYS BANK (U) LTD. BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE CHILDRENS FOUNDATION 14 1000098610 UGANDA 15 1000026105 BIDCO UGANDA LIMITED 16 1000026050 BOLLORE AFRICA LOGISTICS UGANDA LIMITED 17 1000038228 BRITISH AIRWAYS 18 1000124037 BYANSI FISHERIES LTD 19 1000024548 CENTENARY RURAL DEVELOPMENT BANK LIMITED 20 1000024303 CENTURY BOTTLING CO. LTD. 21 1001017514 CHILDREN AT RISK ACTION NETWORK 22 1000691587 CHIMPANZEE SANCTUARY & WILDLIFE 23 1000028566 CITIBANK UGANDA LIMITED 24 1000026312 CITY OIL (U) LIMITED 25 1000024410 CIVICON LIMITED 26 1000023516 CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY -

Professor Christine DRANZOA Muni University P.O

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Christine DRANZOA Muni University P.O. Box 725 Arua, Uganda. Tel: +256(0)476420313. Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Profession: Wildlife Ecologist, Conservationist, Educationalist, Facilitator and Administrator. 1.0 Educational Background BSc, Makerere University. Upper Second (Hon’s) 1987 Master of Science, Makerere University 1991 Diploma on Modern Management and Administration, Cambridge Tutorial Coll 1994 Ph.D. (Zoology), Makerere University-Uganda 1997 Certificate in Conservation Genetics (Uganda) 1996 Certificate in Conservation Biology, University of Illinois, USA 1997 Certificate in Financial Management & Accounting for non-Accountants 2001 Certificate in Project Planning and Management, Uganda Management Institute 2002 Certificate in Social Skills (Rock Fellow Foundation - Makerere University) 2003-4 Certificate in International Women’s Leadership Forum 2004-5 Certificate in PhD supervision (PREPARE PhD Programme) 2009 Certificate in Corporate Governance 2014 2.0 Current Position Professor, Acting Vice Chancellor, Muni University, P.O. Box Arua, Uganda. In June 2014, she was appointed in the position of Acting Vice Chancellor Muni University She provides overall Administrative, Academic, Research and Financial oversight for the Institution. Others • President, Forum for African Women Educationalist (FAWE) Nairobi • Fellow, Uganda National Academy of Science and Member on the Climate Change Committee • Uganda Government Appointee on Senate of Busitema University • Chairperson, Management Board, -

Stanbic Branches

UGANDA REVENUE AUTHORITY BANK ACCOUNTS FOR TAX COLLECTIONS BANK/ BRANCH STATION ACCOUNT NUMBER STANBIC BRANCHES STANBIC KABALE Kabale DT 014 0069420401 STANBIC KIHIHI Kihihi Ishasha 014 0072016701 STANBIC KISORO Kisoro DT 014 0067695501 STANBIC KITGUM Kitgum E&C 014 0013897701 STANBIC MOYO Moyo DT 014 0094774501 STANBIC NEBBI Nebbi Main 014 0093252701 STANBIC CUSTOMS Ntungamo Mirama 014 0059793301 STANBIC PAKWACH Pakwach CUE 014 0096061101 STANBIC GULU Gulu 014 00 87598001 STANBIC APAC Apac 014 0089064501 STANBIC LIRA Lira 014 0090947601 STANBIC KIBOGA Kiboga 014 0032789101 STANBIC MUBENDE Mubende 014 0029903401 STANBIC MITYANA Mityana 014 0028053701 STANBIC KYOTERA Kyotera 014 0064697901 STANBIC MUKONO Mukono 014 0023966401 STANBIC ARUA Arua DT 014 0091518701 STANBIC JINJA Jinja LTO 014 0034474801 STANBIC TORORO Tororo DT 014 0039797301 STANBIC NAKAWA 014 0014526801 STANBIC KAMPALA City ‐Corporate 014 00 62799201 Corporate‐Corporate 014 00 62799201 Lugogo‐Corporate 01400 62799201 STANBIC SOROTI Soroti 014 0050353901 STANBIC KASESE Kasese DT, Kasese CUE 014 00788089 01 STANBIC LUWERO Luwero(Kampala North) 014 00253024 01 STANBIC MOROTO Moroto 014 00486049 01 STANBIC WANDEGEYA Kampala North DT 014 00051699 01 STANBIC BUSIA Busia DT 014 00409365 01 STANBIC F/PORTAL F/Portal 014 00770127 01 STANBIC IGANGA Iganga 014 00 363457 01 STANBIC MALABA Malaba 014 00 420444 01 STANBIC MASAKA Masaka 014 00 824562 01 STANBIC MBALE Mbale DT 014 00 444509 01 STANBIC MBARARA Mbarara 014 00 537253 01 1 BANK/ BRANCH STATION ACCOUNT NUMBER STANBIC BUSHENYI -

RUFORUM Biennial Conference 2018

The Sixth African Higher Education Week RUFORUM Biennial Conference 2018 22 - 26 October, 2018 | KICC - Kenya Theme: Aligning African Universities to Accelerate Attainment of Africa’s Agenda 2063 Our Motivation “Transforming agriculture in Africa requires innovative scientific research, educational and training approaches. The education sector Our Motivation, further reinforced by the Science needs to be more connected to the new Agenda for Agriculture in Africa challenges facing rural communities and needs to build capacity of young people to be part of the transformation of the agricultural sector” RUFORUM VISION 2030 AT A GLANCE RUFORUM Vibrant, transformative universities catalysing sustainable, inclusive VISION 2030 agricultural development to feed and create prosperity for Africa TAGDev RANCH CREATE K-Hub RUFORUM Transforming African Regional Anchor Cultivating Knowledge Hub Agricultural Universities Universities Research for University Flagship to meaningfully for Agricultural and Teaching Networking, Programmes contribute to Higher Excellence Partnerships and Africa’s Growth and Education Advocacy Development • Student learning: Providing opportunities for transformative student learning. • Research excellence: Creating and advancing knowledge to improve the quality of life. • Community engagement: Serving and engaging society to enhance economic, social and cultural well-being. • Enhancing innovation: Creating opportunities that promote cooperative action among the public, private and civil sectors to leverage resources to RUFORUM stimulate innovation. Commitments • Knowledge generation and sharing: Enhancing knowledge exchange to drive positive change in Africa’s food and agriculture and higher agricultural education systems. • Support to policy dialogue and reform: Connecting and challenging leaders to champion policy innovation, elevate policies as national priorities and catalyse action for transformation. • Fulfilling the potential of women in agricultural science, technology and innovation. -

Press Review January 2016, Edition 7

PRESS REVIEW John Paul II Justice and Peace Centre “Faith Doing Justice” EDITION 7 JANUARY 2016 THEMATIC AREAS Plot 2468 Nsereko Road-Nsambya Education P.O. Box 31853, Kampala-Uganda Environment Tel: +256414267372 Health Mobile: 0783673588 Economy Email: [email protected] Religion and Society [email protected] Youth Website: www.jp2jpc.org EDUCATION Students failed to Graduate over wrong course unit. Among hundreds who missed this year’s graduation at Makerere University are students from the department of Performing Arts and Film, who were affected because they were enrolled on a wrong course unit. The University Vice Chancellor, Prof. John Ddumba-Ssentamu, said that, is to blame for the mistake and is planning a programme to ensure that the affected students study the right course. Global Junior School, Nkokonjeru, tops PLE in 2015. In Kampala, with all its 143 pupils passing in first Division, Global Junior School in Mukono district, led a group of other 34 schools with 100 per cent first grade in the 2015 Primary Leaving Examinations (PLE) results released. Bukenya bows out, Odongo takes over UNEB. The Uganda National Examinations Board announced the departure of long serving Executive Secretary Mathew Bukenya who will be replaced by his deputy, Mr Daniel Nokrach Odongo. UNEB chairman prof. Mary Okwakol said that Mr Odongo, who joined the Examinations body 11 years ago will assume his duties on April 1. Examination results of 900 pupils withheld over malpractice. Results for at least 909 pupils who sat their Primary Leaving Examinations (PLE) last year were withheld by Uganda National Examination Board (UNEB) over malpractices. -

HERS-EA SECOND ACADEMY JULY 2ND- 6TH 2018 REPORT Pathways

HERS-EA SECOND ACADEMY JULY 2ND- 6TH 2018 REPORT Pathways to Leadership in Higher Education: New Approaches to Turning Dreams into Career Plans. Prepared for HERS-EA by Racheal Hope Namubiru Auma 1 | P a g e Group portrait of some 2018 HERS-EA facilitators after the keynote address. 2 | P a g e Table of Content List of acronyms ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 List of tables………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………9 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 2. Section 1- Day 1 2.1. Welcome remark ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………12 2.2. Vice Chancellor remark…………………………………………………………………………………………………..13 2.3. Keynote address……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..15 2.4. Gender mainstreaming…………………………………………………………………………………………………..17 2.5 Assessing barriers to female advancement in HE: Eagles or chicken?...............................19 2.5.1 Group discussion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….19 2.5.2 Wrap-up: Personal reflection…………………………………………………………………………………………19 3. Section 2- Day 2 3.1. Introduction to grant writing…………………………………………………………………………………………22 3.2. Looking at active grants…………………………………………………………………………………………………23 3.3 Budgeting for grants………………………………………………………………………………………………………24 3.3. Gender stereotypes, sexism, and discrimination in HE………………………………………………….25 3.3.1 Group discussion outputs……………………………………………………………………………………………..26 4. Section 3- Day 3 3 | P a g e 4.1 Budgeting for intuitions in HE: Case study…………………………………………………………………….28 -

UGANDA CLEARING HOUSE RULES and PROCEDURES March 2018

UGANDA CLEARING HOUSE RULES AND PROCEDURES March 2018 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ UGANDA CLEARING HOUSE RULES AND PROCEDURES March 2018 BANK OF UGANDA UGANDA BANKERS’ASSOCIATION P.O.BOX 7120 P.O.BOX 8002 KAMPALA KAMPALA 1 | P a g e UGANDA CLEARING HOUSE RULES AND PROCEDURES March 2018 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Amendment History Version Author Date Summary of Key Changes 0.1 Clearing House 2009 Initial clearing house rules Committee 0.2 Clearing House 2011 Amendments included: Committee Inclusion of the 2nd clearing session. Inclusion of the pigeon hole’s clearing Inclusion of fine of Ugx.10,000 for each EFT unapplied after stipulated period. 0.3 Clearing House 2014 Amendments include: Committee Revision of the Direct Debit rules and regulations to make them more robust. Revision of the fine for late unapplied EFTs from Ugx.10,000 to Ugx.20,000 per week per transaction. Included the new file encryption tool GPG that replaced File Authentication System (FAS). Included a schedule for the upcountry clearing process. Discontinued the use of floppy disks as acceptable medium for transmitting back-up electronic files. The acceptable media is Flash disks and Compact Disks only. Revised the cut-off time for 2nd session files submission from 2.00p.m to 3.00p.m Updated the circumstances under which membership can be terminated. Revised committee quorum. 0.4 Clearing House 2018 Updated the rules to reflect the Committee requirements for the new automated clearing house with cheque truncation capability. Provided an inward EFT credits exceptions management process. REVIEW MECHANISM This procedure manual should be updated every two years or as and when new processes or systems are introduced or when there are major changes to the current process. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.B / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

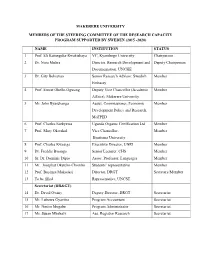

(2015 -2020) Name In

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY MEMBERS OF THE STEERING COMMITTEE OF THE RESEARCH CAPACITY PROGRAM SUPPORTED BY SWEDEN (2015 -2020) NAME INSTITUTION STATUS 1 Prof. Eli Katunguka-Rwakishaya VC, Kyambogo University Chairperson 2 Dr. Nora Mulira Director, Research Development and Deputy Chairperson Documentation, UNCHE 3 Dr. Gity Behravan Senior Research Advisor, Swedish Member Embassy 4 Prof. Ernest Okello-Ogwang Deputy Vice Chancellor (Academic Member Affairs), Makerere University 5 Mr. John Byaruhanga Assist. Commissioner, Economic Member Development Policy and Research, MoFPED 6 Prof. Charles Ssekyewa Uganda Organic Certification Ltd Member 7 Prof. Mary Okwakol Vice Chancellor, Member Busitema University 8 Prof. Charles Kwesiga Executive Director, UNRI Member 9 Dr. Freddie Bwanga Senior Lecturer, CHS Member 10 Sr. Dr. Dominic Dipio Assoc. Professor, Languages Member 11 Mr. Josephat Oketcho-Chombo Students’ representative Member 12 Prof. Buyinza Mukadasi Director, DRGT Secretary/Member 13 To be filled Representative, UNCST Secretariat (DR>) 14 Dr. David Owiny Deputy Director, DRGT Secretariat 15 Mr. Lubowa Gyaviira Program Accountant Secretariat 16 Mr. Nestor Mugabe Program Administrator Secretariat 17 Ms. Susan Mbabazi Ass. Registrar Research Secretariat MAKERERE UNIVERSITY MEMBERS OF THE IMPLEMENTATION COMMITTEE OF THE RESEARCH CAPACITY PROGRAM SUPPORTED BY SWEDEN (2015 -2020) NAME COLLEGE/SCHOOL STATUS 1 Prof. Buyinza Mukadasi DRGT Chairperson 2 Dr. David Owiny DRGT Deputy Chairperson 3 Prof. James Tumwine CHS Member 4 Prof. Celestine Obua CHS Member 5 Dr. Gilbert Maiga COCIS Member 6 Dr. Andrew Ellias State CHUSS Member 7 Dr. Lydia Mazzi Kayondo CEDAT Member 8 Dr. Engineer Bainomugisha COCIS Member 9 Dr. Herbert Talwana CAES Member 10 Dr. David Guwatudde CHS Member 11 Dr. -

Housing Finance in Kampala, Uganda: to Borrow Or Not to Borrow

Housing Finance in Kampala, Uganda: To Borrow or Not to Borrow ANNIKA NILSSON Doctoral Thesis Stockholm, Sweden 2017 KTH Centre for Banking and Finance Dept. of Real Estate and Construction Management TRITA FOB-DT-2017:2 SE-100 44 Stockholm ISBN 978-91-85783-75-5 SWEDEN Akademisk avhandling som med tillstånd av Kungl Tekniska högskolan framlägges till offentlig granskning för avläggande av teknologie doktorsexamen i Fastigheter och byggande tisdagen den 28:e mars 2017 kl 13:00 i rum F3, Lindstedtsvägen 26, Kungliga Tekniska högskolan, Stockholm. © Annika Nilsson, februari 2017 Tryck: Universitetsservice US AB Abstract Housing is an important part of development processes and typically re- quires long-term finance. Without long-term financial instruments, it is difficult for households to smooth income over time by investing in housing. However, in developing countries the use of long-term loans is limited, particularly among the middle-class and lower income individuals. Most people in developing coun- tries build their houses incrementally over time without long-term loans. The limited use of long-term loans is generally seen as a symptom of market failures and policy distortions. This thesis empirically explores constraints to increase housing loans and factors that determinate the demand for different types of loans for investment in land and residential housing. The study is conducted in Kampala, the capital of Uganda. The thesis looks at supply and demand of loans. Most of the data on the supply side is collected through interviews and literature studies. The demand side is investigated through questionnaires to household where data is collected in four surveys targeting different household groups. -

Uganda Housing Market Mapping and Value Chain Analysis

UGANDA HOUSING MARKET MAPPING AND VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS 2013 1 2 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................................. 5 ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................. 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 8 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 13 2. MARKET MAPPING METHODOLOGY ................................................................................... 15 2.1 Methodological Approach .............................................................................................. 15 2.2 The Target Population .................................................................................................... 18 3. COUNTRY CONTEXT .............................................................................................................. 20 3.1 Access to Housing ........................................................................................................... 20 3.2 The Policy Environment .................................................................................................. 21 3.3 Overview of the Land Market in Uganda ........................................................................ 23 4. HOUSING VALUE CHAIN MARKET MAPS .............................................................................