Chapter I. the Steam Engine As a Simple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MACHINES OR ENGINES, in GENERAL OR of POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, Eg STEAM ENGINES

F01B MACHINES OR ENGINES, IN GENERAL OR OF POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, e.g. STEAM ENGINES (of rotary-piston or oscillating-piston type F01C; of non-positive-displacement type F01D; internal-combustion aspects of reciprocating-piston engines F02B57/00, F02B59/00; crankshafts, crossheads, connecting-rods F16C; flywheels F16F; gearings for interconverting rotary motion and reciprocating motion in general F16H; pistons, piston rods, cylinders, for engines in general F16J) Definition statement This subclass/group covers: Machines or engines, in general or of positive-displacement type References relevant to classification in this subclass This subclass/group does not cover: Rotary-piston or oscillating-piston F01C type Non-positive-displacement type F01D Informative references Attention is drawn to the following places, which may be of interest for search: Internal combustion engines F02B Internal combustion aspects of F02B 57/00; F02B 59/00 reciprocating piston engines Crankshafts, crossheads, F16C connecting-rods Flywheels F16F Gearings for interconverting rotary F16H motion and reciprocating motion in general Pistons, piston rods, cylinders for F16J engines in general 1 Cyclically operating valves for F01L machines or engines Lubrication of machines or engines in F01M general Steam engine plants F01K Glossary of terms In this subclass/group, the following terms (or expressions) are used with the meaning indicated: In patent documents the following abbreviations are often used: Engine a device for continuously converting fluid energy into mechanical power, Thus, this term includes, for example, steam piston engines or steam turbines, per se, or internal-combustion piston engines, but it excludes single-stroke devices. Machine a device which could equally be an engine and a pump, and not a device which is restricted to an engine or one which is restricted to a pump. -

FUSION ENERGY FOUNDATION December 197^ $2.00/ .25

MAGAZINE OF THE FUSION ENERGY FOUNDATION December 197^ $2.00/ .25 Steam Power How It Was Delayed 100 Years FUSION Features 26 Leibniz, Papin, and the Steam Engine: MAGAZINE Of THE FUSION ENERGY FOUNDATION A Case Study of British Sabotage Vol. 3, No. 3 Philip Valenti December 1979 ISSN 0148-0537 Impact Fusion: A New Look at an Old Idea Dr. John Schoonover 53 The North American Water and Power Alliance Proposal: Creating Water Resources for the Year 2000 Calvin Larson EDITORIAL STAFF News Editor-in-Chief Dr. Morris Levitt SPECIAL REPORT Associate Editor 8 Cambodia: The Destruction of a Civilization Dr. Steven Bardwell INTERNATIONAL Managing Editor 12 Mexican President Urges 'Power of Reason' to Resolve Marjorie Mazel Hecht Energy Crisis Fusion News Editor 13 Neporozhniy Dedicates First MHD Facility Charles B. Stevens 13 Saudi Oil Minister Endorses Fusion 13 New Soviet Plan Puts Science First Energy News Editors William Engdahl 14 Brazil's Energy—Nuclear or Biogas Marsha Freeman 14 FEF Designs Nuclear Plan for India NATIONAL Editorial Assistant Christina Nelson Huth 15 Shutdown of Hanford Facility Threatens Cancer Research 16 TVA Head Says 'No' to Nuclear Art Director Christopher Sloan 16 Meat Processors Urge U.S. to Co Nuclear WASHINGTON Assistant Art Director 17 FEF Postcard Campaign: Put Fusion On Line by 1995 Deborah Asch 17 McCormack Submits Add-On to Fusion Budget Graphics Assistants 18 Rep. Wydler Defuses Nuclear Safety Hysteria Gillian Cowdery 18 Presidential Commission May Call for Nuclear Moratorium Gary Genazzio 19 GAO Pans Fusion as 'Unknown' Advertising Manager FUSION NEWS Norman Pearl 21 Soviets Report Promising Results with Field-Reversed Fusion Subscription and 22 Sandia Shows Progress with Light Ion Beams Circulation Manager 22 Livermore Proposes New Fusion Approach Cynthia Parsons 22 PLT Scientists Report Observation of Thermonuclear Neutrons FUSION is published monthly, 10 times a year except CONFERENCES September and April, by the Fusion Energy Foundation 24 The Beginning of a Determinist Theory of Turbulence (FEF), 888 7th Ave., 24th Floor. -

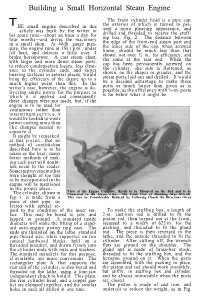

Building a Small Horizontal Steam Engine

Building a Small Horizontal Steam Engine The front cylinder head is a pipe cap, THE small engine described in this the exterior of which is turned to pre- article was built by the writer in sent a more pleasing appearance, and his spare time—about an hour a day for drilled and threaded to receive the stuff- four months—and drives the machinery ing box, Fig. 2. The distance between in a small shop. At 40-lb. gauge pres- the edge of the front-end steam port and sure, the engine runs at 150 r.p.m., under the inner side of the cap, when screwed full load, and delivers a little over .4 home, should be much less than that brake horsepower. A cast steam chest, shown, not over ¼ in., for efficiency, and with larger and more direct steam ports, the same at the rear end. When the to reduce condensation losses; less clear- cap has been permanently screwed on ance in the cylinder ends, and larger the cylinder, one side is flattened, as bearing surfaces in several places, would shown, on the shaper or grinder, and the bring the efficiency of the engine up to a steam ports laid out and drilled. It would much higher point than this. In the be a decided advantage to make these writer's case, however, the engine is de- ports as much larger than given as is livering ample power for the purpose to possible, as the efficiency with ½-in. ports which it is applied, and consequently is far below what it might be. -

Steam and You! How Steam Engines Helped the United States to Expand Reading

Name____________________________________ Date ____________ Steam and You! How Steam Engines Helped The United States To Expand Reading How Is Steam Used To Help People? (Please fill in any blank spaces as you read) Have you ever observed steam, also known as water vapor? For centuries, people have observed steam and how it moves. Describe steam on the line below. Does it rise or fall?____________________________________________________________ Steam is _______ and it ___________. When lots of steam moves into a pipe, it creates pressure that can be used to move things. Inventors discovered about 300 years ago that they could use steam to power machines. These machines have transformed human life. Steam is used today to help power ships and to spin large turbines that generate electricity for millions of people throughout the world. The steam engine was one of the most important inventions of the Industrial Revolution that occurred about from about 1760 to 1840. The Industrial Revolution was a time when machine technology rapidly changed society. Steam engines were used to power train locomotives, steamboats, machines in factories, equipment in mines, and even automobiles before other kinds of engines were invented. Boiling water in a tea kettle produces A steamboat uses a steam engine to steam. Steam can power a steam engine. turn a paddlewheel to move the boat. A steam locomotive was powered when A steam turbine is a large metal cylinder coal or wood was burned inside it to boil with large fan blades that can spin when water to make steam. The steam steam flows through its blades. -

Hydro Internal Combustion Engine

International Journal of Mechanical And Production Engineering, ISSN: 2320-2092, Volume- 2, Issue- 7, July-2014 HYDRO INTERNAL COMBUSTION ENGINE SAMEET KESHARI PATI Student, Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, 2nd year, Gandhi Engineering College, Bhubaneswar, Odisha E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- Focus of this study is to give and describe the details of research and workings on hydro IC engine. Hydro IC engine is an engine which would work with water as its fuel. The objective of this work is to decrease the use of non-renewable resources. The world’s population is expected to expand from about 6 billion people to 10 billion people by the year 2050, all striving for a better quality of life. As the Earth’s population grows, so will the demand for energy and the benefits that it brings improved standards of living, better health and longer life expectancy, improved literacy and opportunity, and many others. For the Earth to support its population, we must increase the use of energy supplies that are clean, safe, and cost-effective. This concept of Hydro IC engine works on temperature exchange between two chemical substances which continuously react among themselves and helps us to derive mechanical energy out of it. This concept of engine is based upon a modified version of a normal two stroke engine. This engine consists of piston and cylinder arrangement. The most important thing in this complete work is that this method doesn’t produce any kind of exhaust gases or chemical compounds out of it in the complete cycle. This engine works continuously by using this chemical substance which do not get depleted and could be used again and again. -

The Newcomen Memorial Engine

THE NEWCOMEN MEMORIAL ENGINE INTERNATIONAL HISTORIC THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING MECHANICAL ENGINEERS LANDMARK THE NEWCOMEN SOCIETY DARTMOUTH, DEVON, ENGLAND THE INSTITUTION OF 17/9/1981 MECHANICAL ENGINEERS owards the end of the 17th century the need experimented with in attempts to produce useful for better and cheaper means of removing power, no practical pumping engine was devised until T water from coal and other mines in various partial success was achieved by Thomas Savery’s ‘The areas of Great Britain became pressing. These mines, Miner's Friend’ (patented in 1698). working earlier from the outcrops, had over the years been taken ever deeper and the principal coalmining This machine had no heavy moving parts, using areas of Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Tyneside first a vacuum to ‘suck’ water into a container, and were particularly troubled. Many of the mines had then steam pressure to force the water to a height, been drowned out and abandoned; existing pumps needing only simple valves to control the action. simply could not cope with the water. Suited to but modest lifts, the device was a most impractical arrangement for raising water from Although steam and its effects had been much depths, and so failed its stated purpose. Trunnions. Beam. Arch Head. Little Arch. Chain. Water supply to top of piston. Cylinder. Pump Rod. Piston. Water Jet. Pump Rod. Eduction Injection Pipe. Water Valve. Steam Pipe. Steam Valve. Snifting Boiler. Valve. Injection Water Pump. The principal features of the Newcomen engine in section. Steam is generated at atmospheric pressure in the boiler and fills the cylinder during the upward stroke of the piston. -

The L3 Exhibitions Catalogue 2010-2014

The L3 Exhibitions Catalogue 2010-2014 Leonardo da Vinci overview Leonardo da Vinci is a universal genius. He What the public knows about Leonardo is bare- was, of course, an Italian, but he belongs to a ly the tip of the iceberg. His manuscripts con- past that is part of the cultural heritage of every tinue to hide secrets and are worthy of inquiry person and every nation. He is a singular exam- and presentation in new, innovative ways. L3 ple throughout history of a man who possessed explores, discovers and reveals the “unknown an enormous talent and excelled not only as a Leonardo” in order to spark the hidden genius scientist, but also as an artist. Most of the inven- that lies within us all. tions and machines that he designed can in fact be considered works of art. On the same note, Leonardo3 (L3) is the world leader in exclu- his artistic works are both the creations of a sive exhibitions and publications on da Vinci’s master artist and the products of a formidable genius. Each of our exhibitions is the result of scientific brain. work carried out by our own team of researchers who investigate and develop never-seen-before Just as his paintings deserve the kind of investi- machines for each event. gation to which only today’s technology can do justice, so the full extent of his scientific work Our exhibitions are “dynamic” rather than “stat- has yet to be revealed to the public. ic”. We make extensive use of 3D animations, physical models and interactive software to of- fer the public a unique level of interaction and a hands-on “edu-tainment” experience. -

WSA Engineering Branch Training 3

59 RECIPROCATING STEAM ENGINES Reciprocating type main engines have been used to propel This is accomplished by the guide and slipper shown in the ships, since Robert Fulton first installed one in the Clermont in drawing. 1810. The Clermont's engine was a small single cylinder affair which turned paddle wheels on the side of the ship. The boiler was only able to supply steam to the engine at a few pounds pressure. Since that time the reciprocating engine has been gradually developed into a much larger and more powerful engine of several cylinders, some having been built as large as 12,000 horsepower. Turbine type main engines being much smaller and more powerful were rapidly replacing reciprocating engines, when the present emergency made it necessary to return to the installation of reciprocating engines in a large portion of the new ships due to the great demand for turbines. It is one of the most durable and reliable type engines, providing it has proper care and lubrication. Its principle of operation consists essentially of a cylinder in which a close fitting piston is pushed back and forth or up and down according to the position of the cylinder. If steam is admitted to the top of the cylinder, it will expand and push the piston ahead of it to the bottom. Then if steam is admitted to the bottom of the cylinder it will push the piston back up. This continual back and forth movement of the piston is called reciprocating motion, hence the name, reciprocating engine. To turn the propeller the motion must be changed to a rotary one. -

Steam Consumption of Pumping Machinery

Steam Consumption of Pumping Machinery HENRY EZRA KEENEY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING IN THE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESENTED JUNE, 19Q0 THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ____________ ______ Henry.Ezra.Keeney........_... entitled..s.ta.ara.C.an8mp.i.io.n.....Q.£ ...Bumping.. Machinery. IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE o f ....Bachelor.of.Science.in.Mechanical...Engineering.* h e a d o f d e p a r t m e n t o f ........Mechanical.Engineering, ' INTRODUCTION. Those who have not considered the subject of water distribu tion* may not believe that pumping machinery stands at the head of the various branches of Engineering. As to the truth of this state ment, we 'nave only to consider that coal could not be obtained with out the pumping engine; our water supply for boilers and our city water supply would be difficult of management if it were not for the pump. ”’ater is found in every mine, to a greater or less extent, and the first applications of steam were for pumping the water out of these mines. HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT. Many forms of puraps were used for obtaining water, but not until the 17th century was steara used for pumping water. So man ifest was the economy of steam pumps over those driven by horses, (which were previously used to a great extent) even at the begin ning, that they were introduced as rapidly as they could be fur nished with the limited supply of tools at the command of the en gine and boiler builders of that day. -

141210 the Rise of Steam Power

The rise of steam power The following notes have been written at the request of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Transport Division, Glasgow by Philip M Hosken for the use of its members. The content is copyright and no part should be copied in any media or incorporated into any publication without the written permission of the author. The contents are based on research contained in The Oblivion of Trevithick by the author. Section A is a very brief summary of the rise of steam power, something that would be a mighty tome if the full story of the ideas, disappointments, successes and myths were to be recounted. Section B is a brief summary of Trevithick’s contribution to the development of steam power, how he demonstrated it and how a replica of his 1801 road locomotive was built. Those who study early steam should bear in mind that much of the ‘history’ that has come down to us is based upon the dreams of people seen as sorcerers in their time and bears little reality to what was actually achieved. Very few of the engines depicted in drawings actually existed and only one or two made any significant contribution to the harnessing of steam power. It should also be appreciated that many drawings are retro-respective and close examination shows that they would not work. Many of those who sought to utilise the elusive power liberated when water became steam had little idea of the laws of thermodynamics or what they were doing. It was known that steam could be very dangerous but as it was invisible, only existed above the boiling point of water and was not described in the Holy Bible its existence and the activities of those who sought to contain and use it were seen as the work of the Devil. -

Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy

A Dissertation entitled “Keep Your Dirty Lights On:” Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy Exceptionalism in American Society by Daniel A. French Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History _________________________________________ Dr. Diane F. Britton, Committee Chairperson _________________________________________ Dr. Peter Linebaugh, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Daryl Moorhead, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Kim E. Nielsen, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Patricia Komuniecki Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2014 Copyright 2014, Daniel A. French This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the express permission of the author. An Abstract of “Keep Your Dirty Lights On:” Electrification and the Ideological Origins of Energy Exceptionalism in American Society by Daniel A. French Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in History The University of Toledo December 2014 Electricity has been defined by American society as a modern and clean form of energy since it came into practical use at the end of the nineteenth century, yet no comprehensive study exists which examines the roots of these definitions. This dissertation considers the social meanings of electricity as an energy technology that became adopted between the mid- nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth centuries. Arguing that both technical and cultural factors played a role, this study shows how electricity became an abstracted form of energy in the minds of Americans. As technological advancements allowed for an increasing physical distance between power generation and power consumption, the commodity of electricity became consciously detached from the steam and coal that produced it. -

Aqueous Alteration on Main Belt Primitive Asteroids: Results from Visible Spectroscopy1

Aqueous alteration on main belt primitive asteroids: results from visible spectroscopy1 S. Fornasier1,2, C. Lantz1,2, M.A. Barucci1, M. Lazzarin3 1 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC Univ Paris 06, Univ. Paris Diderot, 5 Place J. Janssen, 92195 Meudon Pricipal Cedex, France 2 Univ. Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cit´e, 4 rue Elsa Morante, 75205 Paris Cedex 13 3 Department of Physics and Astronomy of the University of Padova, Via Marzolo 8 35131 Padova, Italy Submitted to Icarus: November 2013, accepted on 28 January 2014 e-mail: [email protected]; fax: +33145077144; phone: +33145077746 Manuscript pages: 38; Figures: 13 ; Tables: 5 Running head: Aqueous alteration on primitive asteroids Send correspondence to: Sonia Fornasier LESIA-Observatoire de Paris arXiv:1402.0175v1 [astro-ph.EP] 2 Feb 2014 Batiment 17 5, Place Jules Janssen 92195 Meudon Cedex France e-mail: [email protected] 1Based on observations carried out at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), La Silla, Chile, ESO proposals 062.S-0173 and 064.S-0205 (PI M. Lazzarin) Preprint submitted to Elsevier September 27, 2018 fax: +33145077144 phone: +33145077746 2 Aqueous alteration on main belt primitive asteroids: results from visible spectroscopy1 S. Fornasier1,2, C. Lantz1,2, M.A. Barucci1, M. Lazzarin3 Abstract This work focuses on the study of the aqueous alteration process which acted in the main belt and produced hydrated minerals on the altered asteroids. Hydrated minerals have been found mainly on Mars surface, on main belt primitive asteroids and possibly also on few TNOs. These materials have been produced by hydration of pristine anhydrous silicates during the aqueous alteration process, that, to be active, needed the presence of liquid water under low temperature conditions (below 320 K) to chemically alter the minerals.