Is Fibular Sesamoidectomy a Viable Option for Sesamoiditis? a Retrospective Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pediatric MSK Protocols

UT Southwestern Department of Radiology Ankle and Foot Protocols - Last Update 5-18-2015 Protocol Indications Notes Axial Coronal Sagittal Ankle / Midfoot - Routine Ankle Pain Axial = In Relation to Leg "Footprint" (Long Axis to Foot) T1 FSE PD SPAIR T1 FSE Injury, Internal Derangement Coronal = In Relation to Leg (Short Axis Foot) PD SPAIR STIR Talar OCD, Coalition Protocol Indications Notes Axial Coronal Sagittal Ankle / Midfoot - Arthritis Arthritis Axial = In Relation to Leg "Footprint" (Long Axis to Foot) PD SPAIR PD SPAIR T1 FSE Coronal = In Relation to Leg (Short Axis Foot) STIR T1 SPIR POST T1 SPIR POST Protocol Indications Notes Axial Coronal Sagittal Foot - Routine Pain, AVN Axial = In Relation to Leg "Footprint" (Long Axis to Foot) T1 FSE PD FSE T1 FSE Coronal = In Relation to Leg (Short Axis Foot) PD SPAIR PD SPAIR STIR Protocol Indications Notes Axial Coronal Sagittal Foot - Arthritis Arthritis Axial = In Relation to Leg "Footprint" (Long Axis to Foot) T1 FSE PD SPAIR STIR Coronal = In Relation to Leg (Short Axis Foot) PD SPAIR T1 SPIR POST 3D WATS T1 SPIR POST Protocol Indications Notes Axial Coronal Sagittal Great Toe / MTP Joints Turf Toe Smallest Coil Possible (Microcoil if Available) PD FSE T1 FSE PD FSE Sesamoiditis FoV = Mid Metatarsal Through Distal Phalanges PD SPAIR PD SPAIR PD SPAIR Slice thickness = 2-3 mm, 10% gap Axial = In relation to the great toe (short axis foot) Coronal = In relation to the great toe (long axis foot / footprint) Appropriate Coronal Plane for Both Ankle and Foot Imaging UT Southwestern Department -

Desarrollo De La Podología En España

Desarrollo de la podología en España Virginia Novel Martí ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intelꞏlectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB. -

Overuse Injuries in Elite Athletes

ATHLETES: OVERUSE MRI of Overuse INJURIES VERY COMMON Injury in the Elite Athlete • Muscle William B. Morrison, M.D. Associate Professor of • Joints Radiology Thomas Jefferson • Tendon University Hospital Philadelphia, PA USA • Ligament • Bone [email protected] How is this Relevant to My Practice? • High performance athletes get similar injuries as ‘regular’ people… but: – More of them, & at a younger age MUSCLE / SOFT TISSUE – More commonly imaged – Secondary gain involved INJURY • All the cases here are high performance athletes – but most injuries are conventional • Exceptions – Some weird sport-specific patterns of stress and other injuries – Acute injuries as opposed to overuse •Overuse –DOMS Muscle Injury Delayed Onset Muscle • Acute injury Soreness (DOMS) – Tendon – Myotendinous junction • All athletes are susceptible if they – Muscle belly change training regimen • Athletes tend to work out intensely – leads to muscle injury • Rarely imaged (“no pain no gain”) – Weightlifting / aerobic exercise – 24hr later – soreness – Can be severe, even look like a tear 1 Acute Muscle Injury • Direct → muscle belly, esp quadriceps T2 – esp rugby, football • Indirect → myotendinous junction – eccentric contraction – sudden acceleration / DOMS: Lateral gastrocnemius deceleration Finding can be subtle, even with T2 and fat sat Professional football player Acute Injury – T1 Quadriceps hematoma Muscle belly injury Myotendinous Unit Hit with helmet • Myotendinous Junction – ‘weak link’ of normal myotendinous complex T2 – Common place for injury – Most common mechanism: eccentric contraction (muscle lengthens and contracts at the same High time) T1 = blood Gastrocnemius tear: Grade 1 Muscle Strain “V” sign • Ill-defined edema T2 T1 STIR Weishaupt D, JCAT 2001; 25:677 2 Gd Gd can help identify Grade 2 Muscle Strain subtle muscle injury AKA “Partial Tear” STIR Professional baseball player Grade 1 strain Sartorius m. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, i ^ e others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 PHYSIOLOGIC RESPONSES TO INFLAMMATION IN ISOLATED EQUINE JOINTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University B y Joanne Hardy, D.V.M., M.S. -

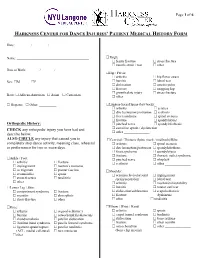

Harkness Center for Dance Injuries' Patient Medical History Form

Page 1 of 6 HARKNESS CENTER FOR DANCE INJURIES’ PATIENT MEDICAL HISTORY FORM Date: ________ / ________ / ________ Name: __________________________________________ Thigh: femur fracture stress fracture muscle strain / tear other_______________ Date of Birth: _______ / _______ / _______ Hip / Pelvis: arthritis hip flexor strain Sex: M F bursitis labral tear dislocation osteitis pubis fracture snapping hip growth plate injury stress fracture Race: African-American Asian Caucasian other _______________ Hispanic Other: __________ Lumbar-Sacral Spine (low back): arthritis sciatica disc herniation/protrusion scoliosis facet syndrome spinal stenosis fracture spondylolysis Orthopedic History: pinched nerve spondylolisthesis CHECK any orthopedic injury you have had and sacroiliac sprain / dysfunction other _______________ describe below. ALSO CIRCLE any injury that caused you to Cervical / Thoracic Spine (neck / mid back)/Ribs: completely stop dance activity, meaning class, rehearsal arthritis spinal stenosis or performance for two or more days. disc herniation/protrusion spondylolisthesis facet syndrome spondylolysis fracture thoracic outlet syndrome Ankle / Foot: pinched nerve whiplash arthritis fracture scoliosis other _______________ impingement morton’s neuroma os trigonum plantar fasciitis Shoulder: sesamoiditis sprain acromioclavicular joint impingement stress fracture tendinitis sprain/separation labral tear other________________ arthritis mechanical instability Lower Leg / Shin: -

Patient Medical History Form

Date of Visit: ________ / ________ / ________ ID # (R=Research) +MR# Patient Medical History Form Name: __________________________________________ Knee: arthritis osgood-schlatter’s Date of Birth: _______ / _______ / _______ Sex: M F bursitis osteochondritis dissecans Social Security ______-_____-________ chondromalacia patellar dislocation iliotibial band syndrome patella femoral syndrome Race: African-American Asian Caucasian ligament sprain/rupture patellar tendinitis Hispanic Other: __________ (ACL, medial collateral) torn meniscus other________________ Address:___________________________________________ ______________________________________________ Thigh: femur fracture stress fracture City: _________________ State: _______ ZIP: ________ muscle strain / tear other_______________ Primary Phone: _______ - ________ - __________ Hip / Pelvis: Email: ___________________________________________ arthritis hip flexor strain bursitis labral tear Emergency Contact Information: dislocation osteitis pubis Name: ___________________________________________ fracture snapping hip growth plate injury stress fracture Relation: ______________ Phone:_____________________ other _______________ Health Insurance Information: Lumbar-Sacral Spine (low back): Name of Insurance Co: _____________________________ arthritis sciatica Name of Policy Holder: _____________________________ disc herniation/protrusion scoliosis facet syndrome spinal stenosis Policy #: _________________ Group#: ________________ fracture spondylolsysis -

Rotator Cuff Tendinitis Shoulder Joint Replacement Mallet Finger Low

We would like to thank you for choosing Campbell Clinic to care for you or your family member during this time. We believe that one of the best ways to ensure quality care and minimize reoccurrences is through educating our patients on their injuries or diseases. Based on the information obtained from today's visit and the course of treatment your physician has discussed with you, the following educational materials are recommended for additional information: Shoulder, Arm, & Elbow Hand & Wrist Spine & Neck Fractures Tears & Injuries Fractures Diseases & Syndromes Fractures & Other Injuries Diseases & Syndromes Adult Forearm Biceps Tear Distal Radius Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Cervical Fracture Chordoma Children Forearm Rotator Cuff Tear Finger Compartment Syndrome Thoracic & Lumbar Spine Lumbar Spine Stenosis Clavicle Shoulder Joint Tear Hand Arthritis of Hand Osteoporosis & Spinal Fx Congenital Scoliosis Distal Humerus Burners & Stingers Scaphoid Fx of Wrist Dupuytren's Comtracture Spondylolysis Congenital Torticollis Shoulder Blade Elbow Dislocation Thumb Arthritis of Wrist Spondylolisthesis Kyphosis of the Spine Adult Elbow Erb's Palsy Sprains, Strains & Other Injuries Kienböck's Disease Lumbar Disk Herniation Scoliosis Children Elbow Shoulder Dislocation Sprained Thumb Ganglion Cyst of the Wrist Neck Sprain Scoliosis in Children Diseases & Syndromes Surgical Treatments Wrist Sprains Arthritis of Thumb Herniated Disk Pack Pain in Children Compartment Syndrome Total Shoulder Replacement Fingertip Injuries Boutonnière Deformity Treatment -

9 10 Ii 12 13 14 15 AGE(YEARS) About 80% of the Patients Came from the City of Oulu Or from the Close Neighbourhood

Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.12.1.4 on 1 March 1978. Downloaded from Brit. J. Sports Med. - Vol. 12, No. 1, March 1978, pp. 4-10 EXERTION INJURIES IN ADOLESCENT ATHLETES S. ORAVA, M.D. and J. PURANEN, M.D. Sports Clinic of Deaconess Institute, Oulu, and Dept. of Surgery, University Central Hospital, Oulu, Finland ABSTRACT A series of 147 cases of exertion injuries in < 15 years old athletes is presented. All injuries occurred during training or athletic performances without trauma and caused symptoms that prevented athletic exercises. There were 67 girls (46%) and 80 boys (54%) in the material. About 90% of them had been training for more than one year before the onset of the symptoms; 65% were interested in track and field athletics, 13% in ball games, 11% in skiing, 4% in swimming, and 3% in orienteering. The rest were interested in other sports. About 33% of the injuries were growth disturbances or osteochondroses seen also in other children. About 15% were anomalies, deformities or earlier osteochondritic changes, which caused first symptoms during the physical exercise; 50% were typical overuse injuries that may bother adult athletes, too; 43% of the injuries were localized in ankle, foot and heel, 31% in knee, 8% in back and trunk, 7% in pelvic and hip region, and the rest in other parts of the body. The injuries were generally slight, no permanent disability was noticed. Rest and conservative therapy cured most cases; operative treatment was used in only eight cases. Adolescent athletes' non-traumatic exertion injuries often differ from the usual overuse syndromes seen in adult athletes (Quinby, Truman et al 1964, Adams 1965, Torg, Pollack et al 1972, Cahill 1973, Schwerdtner & Schobert 1973, Shaffer 1973, Williams & Sperryn 1976). -

Non-Inflammatory Arthritis Non-Inflammatory Arthritis

The webinar will start promptly at the scheduled time All attendees are muted throughout the webinar The moderator will review your questions and present them to the Welcome to lecturer at the end of the presentation At the bottom of your screen are three options for the ViP Adult comments/questions: Chat is to used to make general comments that everyone can see Webinar Raise Your Hand is to be used to notify the Host that you need attention. The Host will send you a private chat in response. Q&A is used to post questions relevant to the lecture. These questions can only be seen by the lecturer and moderator. Approach to the Patient with “Arthritis” Jason Kolfenbach, MD University of Colorado Disclosures I have no disclosures related to the content of this talk. FOCUS ON: Non-inflammatory arthritis Non-inflammatory Arthritis • History • no “believable” red/hot joints • slow steady progression • mechanical pain: use, rest/night • no profound/prolonged morning stiffness • no systemic findings • Physical exam • swelling: • effusion/osteophytes/ligaments • crepitus/grating • local joint line tenderness Acute Non-inflammatory Monoarthritis Trauma Internal derangement (meniscal tear) Osteoarthritis Hemophilia Avascular necrosis Sickle cell disease Transient osteoporosis of the hip Chronic Non-inflammatory Monoarthritis Osteoarthritis Internal derangement Tumors: PVNS (chocolate SF), synovial sarcoma Charcot: Diabetes, syphilis, syringomyelia Others: Avascular necrosis, hemarthrosis (bleeding disorder; coumadin use), synovial chondromatosis -

It's Snow Time!

It’s Snow Time! The Ergonomics of Skiing and Snowboarding By Tamara Mitchell There are several different types of skiing which produce somewhat different strains and possibilities for injury, and snowboarding presents still different strains on the body. By far, the most prevalent recreational type of skiing is Alpine or downhill skiing. Cross-country skiing has gained a lot in popularity, too, and provides the opportunity for a superb aerobic workout outside the usual ski resorts. Telemarking and ski mountaineering are fairly uncommon forms of skiing and since little data exists for these types of skiing injuries, we will not cover them in this article. Snowboarders, though they are on the slopes with the downhill skiers, do not share the same type of techniques nor injuries as skiers. In general, reporting of overuse injuries in professional sports is under reported. Injury data reported can be misleading, since most studies include data from medical facilities at ski resorts that treat primarily traumatic injuries and some research has found significant underreporting of injuries relating to tendons, ligaments, muscles, and joints by medical and technical personnel at World Cup competitions in comparison to problems reported during interviews with the athletes.1 Overuse injuries are likely treated by a medical practitioner at some later time, even months or years after suffering mild discomforts of overuse. Using lost time from sports (training or tournaments) has also not been a good measure of overuse injury incidence since athletes often participate with nagging low-level, persistent pain and frequently do not report it.2 Surveying or questioning athletes about their pain and pain level appears to be a much more relevant way of detecting overuse injuries, though it is rarely used.2 Proper conditioning prior to the snow season is important for all of these sports. -

Body Systems Syllabus

Body Systems Syllabus This syllabus defines the learning competencies, the clinical conditions and normal variants for each body system that trainees are expected to know and demonstrate proficiency in by the end of their training. The clinical conditions and normal variants are categorised into levels of knowledge as defined below. Contents • Definitions 161 ¡ Learning Competencies 162 ¡ Normal Variants 162 ¡ Condition Categories 162 • Abdominal Imaging 162 ¡ Normal Variants 165 ¡ Adult Clinical Conditions 166 • Cardiothoracic Imaging 171 ¡ Learning Competencies 171 ¡ Normal Variants 174 SYSTEMS BODY ¡ Adult Clinical Conditions 174 • Extracranial Head & Neck Imaging 178 ¡ Learning Competencies 178 ¡ Neuro/ENT imaging Normal Variants 180 ¡ Extracranial Head & Neck Imaging Clinical Conditions 181 • Neuroradiology 188 ¡ Learning Competencies 188 ¡ Adult Clinical Conditions 190 • Musculoskeletal Imaging 193 ¡ Learning Competencies 193 ¡ Normal Variants 195 ¡ Adult Clinical Conditions 196 • Paediatric Imaging 211 ¡ Learning Competencies 211 ¡ Paediatric Clinical Conditions 214 • Breast Imaging 222 ¡ Learning Competencies 222 ¡ Breast Normal Variants 225 ¡ Breast Clinical Conditions 225 • Obstetric & Gynaecological Imaging 227 ¡ Learning Competencies 227 ¡ O&G Normal Variants 229 ¡ Clinical Conditions 229 • Vascular Imaging & Interventional Radiology 236 ¡ Learning Competencies 236 ¡ VIR Normal Variants 238 ¡ Adult Clinical Conditions 239 © 2014 RANZCR. Radiodiagnosis Training Program – Curriculum Version 2.2 Page 161 Learning Competencies -

Axial Sesamoiditis in the Horse: a Review

Journal of the South African Veterinary Association ISSN: (Online) 2224-9435, (Print) 1019-9128 Page 1 of 8 Review Article Axial sesamoiditis in the horse: A review Authors: Axial sesamoiditis or osteitis of the proximal sesamoid bones (PSBs) in the horse is described 1 Christelle le Roux as a rare condition. The cause remains unknown and speculative, with vascular, infectious Ann Carstens2 and traumatic aetiologies implicated. It is specifically associated with injury of the palmar or Affiliations: plantar ligament (PL), also known as the intersesamoidean ligament. Imaging findings are 1Department of Companion generally rewarding, and radiological changes are typical, if not pathognomonic, for the Animal Clinical Studies, condition. Lesions consist of bone lysis at the apical to mid-body axial margins of the PSBs, University of Pretoria, South Africa with variable degrees of joint effusion. Radiographic technique warrants careful attention to make a diagnosis, and exposure factors may need to be adjusted. Perineural, intra-articular 2Department of Small Animal and intra-thecal anaesthesia does not seem to provide consistent improvement of lameness Clinical Studies, University of in these cases, with literature reporting inconsistent findings. Ultrasonographic findings Pretoria, South Africa include digital flexor sheath effusion, loss of the normal fibre structure of the PL at its Corresponding author: attachment to the PSBs, abnormal echogenicity or change in thickness of the PL, and irregular Christelle le Roux, hyperechoic cortical margins of the axial margins of the PSBs. Scintigraphy, computed [email protected] tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, although not necessary to make a diagnosis, may add valuable information regarding the location and extent of lesions.