Annual Report and Investigators' Summaries 1959 60

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 11, 1958

CONTENTS Vol. XI, 1958 NO.1 Meetings of the Arctic Circle 1 Officers and Committee members for 19i8 1 Operation Hazen 1957 Z By Piper Cub to the extreme north of Canada 7 The National Film Board Expedition to Eureka, 1956 10 Ornithological research at Pelly Bay in the summer of 1956 11 An electric storm over the north pole 13 Subscriptions for 1958 13 Change of Address 14 Editorial Note 14 NO. Z The Eskimos 15 National Museum expedition to Adelaide Peninsula, 1957 Z4 Geographical Branch survey on Melville Peninsula, 1957 Z7 Inuvik Z9 Arviligjuarmiut names for birds and mammals 30 Change of Address 34 Editorial Note 34 NO.3 Eighty-fifth Meeting 35 Eighty-sixth Meeting 35 The Trail of '98 by the Gravel River Route 35 Road Programme in northern Canada 5Z Department of Transport icebreakers 55 Appointment to the Northwest Territories Council 57 Gazetteer of the Northwest Territories and Yukon 57 "New Aklavik" postmark 57 Subscriptions for 1959 58 - Change of Address 58 • Editorial Note 58 -z NO.4 Activities of the Geological Survey of Canada in the Canadian Arctic, 1958 59 Archaeological work in Ungava and Mansel Island 66 Anthropological field work at Great Whale River and Povung nituk 68 Geographical Branch survey on Melville Peninsula, 1958 71 "Eskimo Yo-Yo" 74 Change of Address 75 Editorial Note 75 - • THE ARCTIC CIRCLE THE COMMITTEE 1958 Officers President: Dr. D.C. Rose Vice-President: Mr. L.A.C.O. Hunt Secretary: Mr. D. Snowden Publications Secretary: Mr. C.J. Marshall (Mr. J.E. Clelan Treasurer: Miss Mary Murphy Editor: Mrs. -

Polar Bears from Space: Assessing Satellite Imagery As a Tool to Track Arctic Wildlife

Polar Bears from Space: Assessing Satellite Imagery as a Tool to Track Arctic Wildlife Seth Stapleton1*¤a, Michelle LaRue3, Nicolas Lecomte4¤b, Stephen Atkinson4, David Garshelis2,5, Claire Porter3, Todd Atwood1 1 United States Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska, United States of America, 2 Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota, United States of America, 3 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America, 4 Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada, 5 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Grand Rapids, Minnesota, United States of America Abstract Development of efficient techniques for monitoring wildlife is a priority in the Arctic, where the impacts of climate change are acute and remoteness and logistical constraints hinder access. We evaluated high resolution satellite imagery as a tool to track the distribution and abundance of polar bears. We examined satellite images of a small island in Foxe Basin, Canada, occupied by a high density of bears during the summer ice-free season. Bears were distinguished from other light-colored spots by comparing images collected on different dates. A sample of ground-truthed points demonstrated that we accurately classified bears. Independent observers reviewed images and a population estimate was obtained using mark– recapture models. This estimate (N^ : 94; 95% Confidence Interval: 92–105) was remarkably similar to an abundance estimate derived from a line transect aerial survey conducted a few days earlier (N^ : 102; 95% CI: 69–152). Our findings suggest that satellite imagery is a promising tool for monitoring polar bears on land, with implications for use with other Arctic wildlife. -

Atlantic Walrus Odobenus Rosmarus Rosmarus

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 65 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 23 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Richard, P. 1987. COSEWIC status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-23 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the status report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Andrew Trites, Co-chair, COSEWIC Marine Mammals Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation du morse de l'Atlantique (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Military Monitoring

Page 1 http://www.carmachicago.com MilAir CARMA Chicago Area Radio Monitoring Association CARMA Military Monitoring An F-16C from the Illinois Air National Guard’s 183rd Tactical Fighter Wing lands at its home base - Abraham Lincoln Memorial airport in Springfield during an Air Rendezvous air show. The state capital building is on the horizon. Command post for the unit was on 138.200 (AM) VHF and 272.175 (AM) UHF. V1.1 Send updates to: [email protected] November 2008 Page 2 http://www.carmachicago.com MilAir CARMA Chicago Area Radio Monitoring Association CARMA V1.1 Send updates to: [email protected] November 2008 Page 3 http://www.carmachicago.com MilAir CARMA Chicago Area Radio Monitoring Association CARMA Mid-air refuelling tracks and anchor areas: Track Primary Secondary Entry / Exit control via ARTCC AR16 343.500 319.700 353.500 343.700 AR17 276.500 320.900 353.700 338.200 AR19 295.400 320.900 360.650 322.500 AR24 295.400 320.900 338.200 353.700 AR105 238.900 320.900 269.000 AR106H 295.800 320.900 269.400 306.200 AR106L 305.500 320.900 269.400 306.200 AR107 324.600 282.700 353.600 AR109H 343.500 320.900 327.100 AR109L 327.600 320.900 327.100 AR110 327.600 319.700 277.400 346.400 319.000 AR111 348.900 319.700 122.200 124.200 132.375 124.275 257.600 288.350 354.150 AR116 366.300 260.200 269.400 343.700 363.200 AR206H 348.900 282.700 323.000 354.100 AR206L 235.100 282.700 323.000 307.800 AR217 283.900 282.700 298.950 294.650 AR218 352.600 282.700 299.200 379.200 AR219 366.300 282.700 363.100 288.300 AR220 352.600 282.700 -

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line: a Bibliography and Documentary Resource List

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line: A Bibliography and Documentary Resource List Prepared for the Arctic Institute of North America By: P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. Matthew J. Farish, Ph.D. Jennifer Arthur-Lackenbauer, M.Sc. October 2005 © 2005 The Arctic Institute of North America ISBN 1-894788-01-X The DEW Line: Bibliography and Documentary Resource List 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PREFACE 2 2.0 BACKGROUND DOCUMENTS 3 2.1 Exchange of Notes (May 5, 1955) Between Canada and the United States Of America Governing the Establishment of a Distant Early Warning System in Canadian Territory.......................................................................................................... 3 2.2 The DEW Line Story in Brief (Western Electric Corporation, c.1960) ……………… 9 2.3 List of DEW Line Sites ……………………………………….…………………….... 16 3.0 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS 23 3.1 Rt. Hon. John George Diefenbaker Centre ……………………………………….…... 23 3.2 Library and Archives Canada …………………………………….…………………... 26 3.3 Department of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage ………………. 46 3.4 NWT Archives Council, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre ……………….... 63 3.5 Yukon Territorial Archives, Whitehorse, YT ………………………………………… 79 3.6 Hudson Bay Company Archives ……………………………………………………... 88 3.7 Archives in the United States ……………………………………………………….… 89 4.0 PUBLISHED SOURCES 90 4.1 The Globe and Mail …………………………………………………………………………… 90 4.2 The Financial Post ………………………………………………………………………….…. 99 4.3 Other Print Media …………………………………………………………………..… 99 4.4 Contemporary Journal Articles ……………………………………………………..… 100 4.5 Government Publications …………………………………………………………….. 101 4.6 Corporate Histories ………………………………………………………………...... 103 4.7 Professional Journal Articles ………………………………………………………..… 104 4.8 Books ………………………………………………………………………………..… 106 4.9 Scholarly and Popular Articles ………………………………………………….……. 113 4.10 Environmental Issues and Cleanup: Technical Reports and Articles …………….…. 117 5.0 OTHER SOURCES 120 5.1 Theses and Dissertations ……………………………………………………………... -

Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic

Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic Dan Brookes DRDC Ottawa Derek F. Scott VP Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) Pip Rudkin UAV Operations Manager PAL Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd Defence R&D Canada – Ottawa Technical Report DRDC Ottawa TR 2013-142 November 2013 Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic Dan Brookes DRDC Ottawa Derek F. Scott VP Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) Pip Rudkin UAV Operations Manager PAL Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd Defence R&D Canada – Ottawa Technical Report DRDC Ottawa TR 2013-142 November 2013 Principal Author Original signed by Dan Brookes Dan Brookes Defence Scienist Approved by Original signed by Caroline Wilcox Caroline Wilcox Head, Space and ISR Applications Section Approved for release by Original signed by Chris McMillan Chris McMillan Chair, Document Review Panel This work was originally sponsored by ARP project 11HI01-Options for Northern Surveillance, and completed under the Northern Watch TDP project 15EJ01 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2013 © Sa Majesté la Reine (en droit du Canada), telle que représentée par le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2013 Preface This report grew out of a study that was originally commissioned by DRDC with Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) in early 2007. With the assistance of PAL’s experience and expertise, the aim was to explore the feasibility, logistics and costs of providing surveillance and reconnaissance (SR) capabilities in the Arctic using private commercial sources. -

Polar Continental Shelf Program Science Report 2019: Logistical Support for Leading-Edge Scientific Research in Canada and Its Arctic

Polar Continental Shelf Program SCIENCE REPORT 2019 LOGISTICAL SUPPORT FOR LEADING-EDGE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN CANADA AND ITS ARCTIC Polar Continental Shelf Program SCIENCE REPORT 2019 Logistical support for leading-edge scientific research in Canada and its Arctic Polar Continental Shelf Program Science Report 2019: Logistical support for leading-edge scientific research in Canada and its Arctic Contact information Polar Continental Shelf Program Natural Resources Canada 2464 Sheffield Road Ottawa ON K1B 4E5 Canada Tel.: 613-998-8145 Email: [email protected] Website: pcsp.nrcan.gc.ca Cover photographs: (Top) Ready to start fieldwork on Ward Hunt Island in Quttinirpaaq National Park, Nunavut (Bottom) Heading back to camp after a day of sampling in the Qarlikturvik Valley on Bylot Island, Nunavut Photograph contributors (alphabetically) Dan Anthon, Royal Roads University: page 8 (bottom) Lisa Hodgetts, University of Western Ontario: pages 34 (bottom) and 62 Justine E. Benjamin: pages 28 and 29 Scott Lamoureux, Queen’s University: page 17 Joël Bêty, Université du Québec à Rimouski: page 18 (top and bottom) Janice Lang, DRDC/DND: pages 40 and 41 (top and bottom) Maya Bhatia, University of Alberta: pages 14, 49 and 60 Jason Lau, University of Western Ontario: page 34 (top) Canadian Forces Combat Camera, Department of National Defence: page 13 Cyrielle Laurent, Yukon Research Centre: page 48 Hsin Cynthia Chiang, McGill University: pages 2, 8 (background), 9 (top Tanya Lemieux, Natural Resources Canada: page 9 (bottom -

Cultural Heritage Resources Report

NTI IIBA for Phase I Draft: Conservation Cultural Heritage Areas Resources Report Cultural Heritage Area: Akpait and and Interpretative Qaqulluit National Wildlife Materials Study Areas Prepared for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 1 May 2011 This report is part of a set of studies and a database produced for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. as part of the project: NTI IIBA for Conservation Areas, Cultural Resources Inventory and Interpretative Materials Study Inquiries concerning this project and the report should be addressed to: David Kunuk Director of Implementation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. 3rd Floor, Igluvut Bldg. P.O. Box 638 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 E: [email protected] T: (867) 975‐4900 Project Manager, Consulting Team: Julie Harris Contentworks Inc. 137 Second Avenue, Suite 1 Ottawa, ON K1S 2H4 Tel: (613) 730‐4059 Email: [email protected] Report Authors: Philip Goldring, Consultant: Historian and Heritage/Place Names Specialist Julie Harris, Contentworks Inc.: Heritage Specialist and Historian Nicole Brandon, Consultant: Archaeologist Note on Place Names: The current official names of places are used here except in direct quotations from historical documents. Throughout the document “Qikiqtarjuaq” refers to the settlement established in the 1950s and previously known as Broughton Island. Except when used in a direct quotation, the term “Broughton Island” in the report refers to the geographic feature (the island) on which the community of Qikiqtarjuaq is located. Names of places that do not have official names will appear as they are found in -

Tab 6 Estimating the Abundance Of

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: X Decision: Issue: South Baffin Island Caribou Abundance Survey, 2012 and Proposed Management Recommendations Background: Caribou are a critical component of the boreal and arctic ecosystems. They are culturally significant to local communities and provide an important source of food. In some areas, there is still uncertainty on population trends because of the lack of scientific information due to difficult logistics and remoteness. This is particularly true for Baffin Island, where three sub-populations of Barrenground caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) are hypothesized, though little is known about their abundance and trends over time (Ferguson and Gauthier 1992). In the past 60 years, only discrete portions of their range have been surveyed and no robust quantitative estimates at the sub-population level were ever derived. For over a decade Inuit from communities on northern Baffin Island, and more recently from across the entire island, have reported declines in caribou numbers, although no quantitative estimates are available. In total 10 communities, representing half of all Nunavummiut, traditionally or currently harvest Baffin Island caribou. At the same time, climate change, including increased arctic temperatures and precipitation, and anthropogenic activities connected to mineral exploration and mining are potentially negatively impacting caribou and their range. Due to the risk of these cumulative negative effects, and the importance of these caribou to communities, the Department of Environment undertook, in 2012, a quantitative caribou abundance aerial survey of South Baffin Island with the support of the NWMB and co- management partners. This area represents the most abundant area of caribou on Baffin Island. -

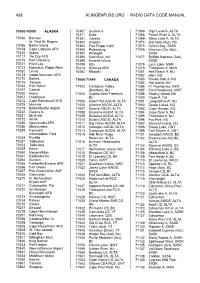

Klingenfuss.Org · Radio Data Code Manual

438 KLINGENFUSS.ORG · RADIO DATA CODE MANUAL 70000-70999 ALASKA 70367 Gustavus 71066 High Level A, ALTA 70371 Sitka 71068 Peace River A, ALTA 70026 Barrow/ 70381 Juneau 71069 Slave Lake A, ALTA W. Post W. Rogers 70383 Angoon 71074 Isachsen (Aut), NU 70086 Barter Island 70385 Five Finger Light 71075 Collins Bay, SASK 70104 Cape Lisburne AFS 70386 Petersburg 71076 Uranium City (Aut), 70116 Wales 70387 Wrangell SASK 70117 Tin City AFS 70395 Ketchikan, Intl. 71077 Buffalo Narrows (Aut), 70119 Port Clarence 70398 Annette Island SASK 70121 Point Lay 70409 Attu 71078 Lynn Lake, MAN 70133 Kotzebue, Ralph Wien 70414 Shemya AFB 71079 Thompson A, MAN 70162 Umiat 70482 Nikolski 71081 Hall Beach A, NU 70173 Indian Mountain AFS 71082 Alert, NU 70174 Bettles 71000-71999 CANADA 71083 Rankin Inlet A, NU 70178 Tanana 71084 Hat Island, NU 70194 Fort Yukon 71003 Callaghan Valley 71086 Ft. Providence, NWT 70197 Central (Biathlon), BC 71087 Fort Providence, NWT 70200 Nome 71004 Cypres Bowl Freestyle, 71088 Rowley Island, NU 70207 Unalakleet BC 71090 Clyde A, NU 70212 Cape Romanzoff AFS 71005 Albert Hall AGCM, ALTA 71091 Longstaff Bluff, NU 70218 Nunivak 71006 Alliance AGCM, ALTA 71092 Dewar Lakes, NU 70219 Bethel/Bethel Airport 71007 Barons AGCM, ALTA 71093 Cape Hooper, NU 70222 Galena A. 71008 Bassano AGCM, ALTA 71094 Cape Dyer A, NU 70231 McGrath 71009 Beiseker AGCM, ALTA 71095 Pond Inlet A, NU 70232 Aniak 71010 Belshill AGCM, ALTA 71096 Fox Five, NU 70235 Sparrevohn AFS 71011 Big Valley AGCM, ALTA 71097 Brevoort Island, NU 70246 Minchumina 71012 Cadogan AGCM, ALTA 71098 Sandy Lake, ONT 70248 Farewell/ 71013 Craigmyle AGCM, ALTA 71099 Fort Severn A, ONT Intermediate Field 71015 Milk River Ridge 71101 Sandspit AWOS, BC 70249 Puntilla Reservoir, ALTA 71102 Rivercourse AGCM, 70251 Talkeetna 71016 Bullhorn Headwaters, ALTA 70252 Talkeetna ALTA 71103 Quesnel AWOS, BC 70259 Kenai 71017 Stefansson Island, NU 71104 Williams Lake A, BC 70260 Nenana/Mun. -

Nunavut Contaminated Sites 0 7

160°W 150°W 140°W 130°W 120°W 110°W 100°W 90°W 80°W 70°W 60°W 50°W 40°W 30°W N ° Nunavut Contaminated Sites 0 7 6 Inset 1 Legend DALE PAYNE ROMULUS LAKE Not Remediated Site Stabilization Remediated Risk Management 5 Remediation in Progress Communities For more information on Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada’s Contaminated Sites Program in Nunavut contact us at [email protected] or 867-975-4500 or visit us at: www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/nunavut. 1 See Inset 1 4 QS-Y384-001-ES-A1 Catalogue: R74-30/2017-1ES ISBN: 978-0-660-08212-7 Printed in 2017 7 3 8 Qausuittuq Qausuittuq National Park Ellesmere Island N National Park ° 0 X 7 GRISE FIORD Melville Island Bathurst Island 2 9 Melville Island Bathurst Island Devon Island 10 Cornwallis Island Cornwallis Island X RESOLUTE d er Soun Risk Management Lancast 7 STOKESX RANGE Parry Channel Sirmilik National Park ay n B f N DRAKE POINT BENT HORN Bylot Island Ba ° 1 4 8 YOUNG INLET 5 6 X REA POINT LOUGHEED ISLAND (L1) POND INLET 2 5 J-34 Somerset Island X CAPE CHRISTIAN 9 ARCTIC BAY e M cl ir ’ C C ILE VANIER tic THOR ISLAND N-12 l c 3 6 i r 10 n A t o c k Prince of Wales X C Island CLYDE RIVER h Amundsen Gulf Victoria Island a n n Gulf of Boothia e l t i a EKALUGAD FIORD KIVITOO r t S a i r CLIFTON POINT o PADLOPING ISLAND t READ ISLAND MERKELYic LAKE DURBAN ISLAND V Larsen Sound FOX-C FOX-D CHAR LAKE BRAY ISLAND Boothia Peninsula ROWLEY ISLAND NADLUARJUK LAKE N PIN-B X ° CAPE PEEL 5 FOX-E 6 FOX-A ROSS POINT FOX-1 QIKIQTARJUAQ X FOX-B PIN-E IGLOOLIK Auyuittuq National Park -

In Northern Foxe Basin, Nunavut

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Central and Arctic Region Science Advisory Report 2014/024 ECOLOGICALLY AND BIOLOGICALLY SIGNIFICANT AREAS (EBSA) IN NORTHERN FOXE BASIN, NUNAVUT Figure 1. Northern Foxe Basin study area (red diagonal lines) with southern boundary line set at 68˚N. Context: During an arctic marine workshop held in 1994, Foxe Basin was identified as one of nine biological hotspots in the Canadian Arctic. In fall 2008 and winter 2009, the Oceans Program in Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Central and Arctic Region conducted meetings in Nunavut with the Regional Inuit Associations, Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., Nunavut Wildlife Management Board and Government of Nunavut to consider areas in Nunavut that might be considered for Marine Protected Area designation. The northern Foxe Basin study area, which includes Fury and Hecla Strait, was selected as one possible area (Figure 1). Based on a request for advice from Oceans Program, a science advisory meeting was held in June 2009 to assess the available scientific knowledge, and consider published local/traditional knowledge, to determine whether one or more locations or areas within the northern Foxe Basin study area would qualify as an Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (EBSA). Two community meetings were subsequently held to incorporate local/traditional knowledge. This Science Advisory Report is from the June 29, 2009 (Winnipeg, MB), September 10, 2009 (Igloolik, NU) and November 19, 2009 (Hall Beach, NU) meetings for the Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas selection process for northern Foxe Basin. Additional publications from this meeting will be posted on the DFO Science Advisory Schedule as they become available.