Anemia in the Andes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 7 Number 2 Pervuvian Trajectories of Sociocultural Article 13 Transformation December 2013 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Silva, Ernesto (2013) "Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol7/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emesto Silva Journal of Global Initiatives Volume 7, umber 2, 2012, pp. l83-197 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva 1 The aim of this essay is to provide a panoramic socio-historical overview of Peru by focusing on two periods: before and after independence from Spain. The approach emphasizes two cultural phenomena: how the indigenous peo ple related to the Conquistadors in forging a new society, as well as how im migration, particularly to Lima, has shaped contemporary Peru. This contribu tion also aims at providing a bibliographical resource to those who would like to conduct research on Peru. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

AP ART HISTORY--Unit 5 Study Guide (Non Western Art Or Art Beyond the European Tradition) Ms

AP ART HISTORY--Unit 5 Study Guide (Non Western Art or Art Beyond the European Tradition) Ms. Kraft BUDDHISM Important Chronology in the Study of Buddhism Gautama Sakyamuni born ca. 567 BCE Buddhism germinates in the Ganges Valley ca. 487-275 BCE Reign of King Ashoka ca. 272-232 BCE First Indian Buddha image ca. 1-200 CE First known Chinese Buddha sculpture 338 CE First known So. China Buddha image 437 CE The Four Noble Truthsi 1. Life means suffering. Life is full of suffering, full of sickness and unhappiness. Although there are passing pleasures, they vanish in time. 2. The origin of suffering is attachment. People suffer for one simple reason: they desire things. It is greed and self-centeredness that bring about suffering. Desire is never satisfied. 3. The cessation of suffering is attainable. It is possible to end suffering if one is aware of his or her own desires and puts and end to them. This awareness will open the door to lasting peace. 4. The path to the cessation of suffering. By changing one’s thinking and behavior, a new awakening can be reached by following the Eightfold Path. Holy Eightfold Pathii The principles are • Right Understanding • Right Intention • Right Speech • Right Action • Right Livelihood • Right Effort • Right Awareness • Right Concentration Following the Eightfold Path will lead to Nirvana or salvation from the cycle of rebirth. Iconography of the Buddhaiii The image of the Buddha is distinguished in various different ways. The Buddha is usually shown in a stylized pose or asana. Also important are the 32 lakshanas or special bodily features or birthmarks. -

Major Geographic Qualities of South Asia

South Asia Chapter 8, Part 1: pages 402 - 417 Teacher Notes DEFINING THE REALM I. Major geographic qualities of South Asia - Well defined physiography – bordered by mountains, deserts, oceans - Rivers – The Ganges supports most of population for over 10,000 years - World’s 2nd largest population cluster on 3% land mass - Current birth rate will make it 1st in population in a decade - Low income economies, inadequate nutrition and poor health - British imprint is strong – see borders and culture - Monsoons, this cycle sustains life, to alter it would = disaster - Strong cultural regionalism, invading armies and cultures diversified the realm - Hindu, Buddhists, Islam – strong roots in region - India is biggest power in realm, but have trouble with neighbors - Kashmir – dangerous source of friction between 2 nuclear powers II. Defining the Realm Divided along arbitrary lines drawn by England Division occurred in 1947 and many lives were lost This region includes: Pakistan (East & West), India, Bangladesh (1971), Sri Lanka, Maldives Islands Language – English is lingua franca III. Physiographic Regions of South Asia After Russia left Afghanistan Islamic revivalism entered the region Enormous range of ecologies and environment – Himalayas, desert and tropics 1) Monsoons – annual rains that are critical to life in that part of the world 1 2) Regions: A. Northern Highlands – Himalayas, Bhutan, Afghanistan B. River Lowlands – Indus Valley in Pakistan, Ganges Valley in India, Bangladesh C. Southern Plateaus – throughout much of India, a rich -

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

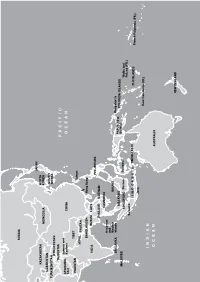

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

Albania's 'Sworn Virgins'

THE LINGUISTIC EXPRESSION OF GENDER IDENTITY: ALBANIA’S ‘SWORN VIRGINS’ CARLY DICKERSON A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN LINGUISTICS YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2015 © Carly Dickerson, 2015 Abstract This paper studies the linguistic tools employed in the construction of masculine identities by burrneshat (‘sworn virgins’) in northern Albania: biological females who have become ‘social men’. Unlike other documented ‘third genders’ (Kulick 1999), burrneshat are not motivated by considerations of personal identity or sexual desire, but rather by the need to fulfill patriarchal roles within a traditional social code that views women as property. Burrneshat are thus seen as honourable and self-sacrificing, are accepted as men in their community, and are treated accordingly, except that they do not marry or engage in sexual relationships. Given these unique circumstances, how do the burrneshat construct and express their identity linguistically, and how do others within the community engage with this identity? Analysis of the choices of grammatical gender in the speech of burrneshat and others in their communities indicates both inter- and intra-speaker variation that is linked to gendered ideologies. ii Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………….. ii Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………………………….. iii List of Tables …………………………………………………………………………..……… viii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………………ix Chapter One – Introduction ……………………………………………………………………... 1 Chapter Two – Albanian People and Language ………………………………………………… 6 2.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………6 2.1 History of Albania ………………………………………………………………………..6 2.1.1 Geographical Location ……………………………………………………………..6 2.1.2 Illyrian Roots ……………………………………………………………………….7 2.1.3 A History of Occupations …………………………………………………………. 8 2.1.4 Northern Albania …………………………………………………………………. -

Oficinas Bbva Horario De Atención : De Lunes a Viernes De 09:00 A.M

OFICINAS BBVA HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN : DE LUNES A VIERNES DE 09:00 A.M. a 6:00 P.M SABADO NO HAY ATENCIÓN OFICINA DIRECCION DISTRITO PROVINCIA YURIMAGUAS SARGENTO LORES 130-132 YURIMAGUAS ALTO AMAZONAS ANDAHUAYLAS AV. PERU 342 ANDAHUAYLAS ANDAHUAYLAS AREQUIPA SAN FRANCISCO 108 - AREQUIPA AREQUIPA AREQUIPA PARQUE INDUSTRIAL CALLE JACINTO IBAÑEZ 521 AREQUIPA AREQUIPA SAN CAMILO CALLE PERU 324 - AREQUIPA AREQUIPA AREQUIPA MALL AVENTURA PLAZA AQP AV. PORONGOCHE 500, LOCAL COMERCIAL LF-7 AREQUIPA AREQUIPA CERRO COLORADO AV. AVIACION 602, LC-118 CERRO COLORADO AREQUIPA MIRAFLORES - AREQUIPA AV. VENEZUELA S/N, C.C. LA NEGRITA TDA. 1 - MIRAFLORES MIRAFLORES AREQUIPA CAYMA AV. EJERCITO 710 - YANAHUARA YANAHUARA AREQUIPA YANAHUARA AV. JOSE ABELARDO QUIÑONES 700, URB. BARRIO MAGISTERIAL YANAHUARA AREQUIPA STRIP CENTER BARRANCA CA. CASTILLA 370, LOCAL 1 BARRANCA BARRANCA BARRANCA AV. JOSE GALVEZ 285 - BARRANCA BARRANCA BARRANCA BELLAVISTA SAN MARTIN ESQ AV SAN MARTIN C-5 Y AV. AUGUSTO B LEGUÍA C-7 BELLAVISTA BELLAVISTA C.C. EL QUINDE JR. SOR MANUELA GIL 151, LOCAL LC-323, 325, 327 CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA JR. TARAPACA 719 - 721 - CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAJAMARCA CAMANA - AREQUIPA JR. 28 DE JULIO 405, ESQ. CON JR. NAVARRETE CAMANA CAMANA MALA JR. REAL 305 MALA CAÑETE CAÑETE JR. DOS DE MAYO 434-438-442-444, SAN VICENTE DE PAUL DE CAÑETE SAN VICENTE DE CAÑETE CAÑETE MEGAPLAZA CAÑETE AV. MARISCAL BENAVIDES 1000-1100-1150 Y CA. MARGARITA 101, LC L-5 SAN VICENTE DE CAÑETE CAÑETE EL PEDREGAL HABILIT. URBANA CENTRO POBLADO DE SERV. BÁSICOS EL PEDREGAL MZ. G LT. 2 MAJES CAYLLOMA LA MERCED JR. TARMA 444 - LA MERCED CHANCHAMAYO CHANCHAMAYO CHICLAYO AV. -

Myzopodidae: Chiroptera) from Western Madagascar

ARTICLE IN PRESS www.elsevier.de/mambio Original investigation The description of a new species of Myzopoda (Myzopodidae: Chiroptera) from western Madagascar By S.M. Goodman, F. Rakotondraparany and A. Kofoky Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, USA and WWF, Antananarivo, De´partement de Biologie Animale, Universite´ d’Antananarivo, Antananarivo, Madagasikara Voakajy, Antananarivo, Madagascar Receipt of Ms. 6.2.2006 Acceptance of Ms. 2.8.2006 Abstract A new species of Myzopoda (Myzopodidae), an endemic family to Madagascar that was previously considered to be monospecific, is described. This new species, M. schliemanni, occurs in the dry western forests of the island and is notably different in pelage coloration, external measurements and cranial characters from M. aurita, the previously described species, from the humid eastern forests. Aspects of the biogeography of Myzopoda and its apparent close association with the plant Ravenala madagascariensis (Family Strelitziaceae) are discussed in light of possible speciation mechanisms that gave rise to eastern and western species. r 2006 Deutsche Gesellschaft fu¨r Sa¨ugetierkunde. Published by Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved. Key words: Myzopoda, Madagascar, new species, biogeography Introduction Recent research on the mammal fauna of speciation molecular studies have been very Madagascar has and continues to reveal informative to resolve questions of species remarkable discoveries. A considerable num- limits (e.g., Olson et al. 2004; Yoder et al. ber of new small mammal and primate 2005). The bat fauna of the island is no species have been described in recent years exception – until a decade ago these animals (Goodman et al. 2003), and numerous remained largely under studied and ongoing other mammals, known to taxonomists, surveys and taxonomic work have revealed await formal description. -

Resumen Cv De Docentes

RESUMEN CV DE DOCENTES NOMBRE DE LA UNIVERSIDAD UNIVERSIDAD CÉSAR VALLEJO S.A.C. MAYOR GRADO PAÍS PERIODO DOCENTE (APELLIDO DOCENTE (APELLIDO ACADÉMICO DEL MENCIÓN DEL MAYOR GRADO DOCENTE PAÍS / UNIVERSIDAD QUE OTORGÓ EL RÉGIMEN DE DEDICACIÓN N° DOCENTE (NOMBRES) (NACIONALID UNIVERSIDAD QUE OTORGÓ EL MAYOR GRADO DOCENTE ACADÉMICO OBSERVACIONES PATERNO) MATERNO) DOCENTE MAYOR GRADO DEL DOCENTE AD) 1 ABAD BAUTISTA LEONOR PERÚ MAESTRO M EN CIENCIAS PARA LA FAMILIA UNIVERSIDAD DE MÁLAGA ESPAÑA TIEMPO PARCIAL 2016-II 2 ABAD DE VITE BLANCA VICTORIA PERÚ DOCTOR D EN CIENCIAS DE LA SALUD UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE PIURA PERÚ TIEMPO PARCIAL 2016-II 3 ABAD ESCALANTE KAROL MOIRA PERÚ Bachiller B EN EDUCACION UNIVERSIDAD MARCELINO CHAMPAGN PER TIEMPO COMPLETO 201602 4 ABANTO AYASTA CARLOS ALBERTO PERÚ MAESTRO M EN SALUD PÚBLICA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE TRUJILLO PERÚ TIEMPO PARCIAL 2016-II ' 5 ABANTO BUITRÓN SHIRLEY JULIANE PERÚ MAESTRO M EN ADMINISTRACIÓN DE NEGOCIOS UNIVERSIDAD PRIVADA CÉSAR VALLEJO PERÚ TIEMPO COMPLETO 2016-II 6 ABANTO VELEZ WALTER IVAN PERÚ DOCTOR D EN ADMINISTRACIÓN DE LA EDUCACIÓN UNIVERSIDAD PRIVADA CÉSAR VALLEJO PERÚ TIEMPO COMPLETO 2016-II 7 ABARCA LALANGUI EDIN HELI PERÚ BACHILLER B EN ECONOMÍA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL PEDRO RUÍZ GALLO PERÚ TIEMPO PARCIAL 2016-II 8 ACETO LUCA PERÚ MAESTRO M EN DESARROLLO, AMBIENTE Y COOPERACIÓN UNIVERSIDAD DE ESTUDIOS DE TURÍN ITALIA TIEMPO COMPLETO 2016-II UNIVERSIDAD EXTRANJERA-NO CUENTAN CON 2DO APELLIDO 9 ACEVEDO ALEGRE YUNI PETRONILA PERÚ BACHILLER B EN ENFERMERÍA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL FEDERICO -

Descargar La Publicación

ENTRE EL ETNOCIDIO Y LA EXTINCION PUEBLOS INDIGENAS aislados, EN CONTACTO INICIAL E INTERMITENTE EN las TIERRAS BAJAS DE BOLIVIA Entre el etnocidio y la extinción: Pueblos indígenas aislados, en contacto inicial e intermitente en las tierras bajas de Bolivia, cuya autoría corresponde al antropólogo Carlos Camacho Nassar es un libro con doble mérito. Primero, es un aporte muy serio y metódico para mostrar la realidad vigente en Bolivia de la problemática que involucra a los grupos indígenas más vulnerables del país, aquellos que han sobrevivido al genocidio histórico que acarreó, sobre todo, la explotación masiva del caucho entre 1880 y 1914. Es también, y ésta tal vez sea la virtud mayor, un libro que aparece en el momento justo, donde la urgencia de denunciar la siempre crítica situación de los Pueblos Indígenas Aislados y la necesidad imperiosa de preservar sus derechos, como indígenas y como humanos, se tensionan de manera dramática, como en el pasado, con los afanes de penetración en las selvas de las empresas trasnacionales y las acciones que conllevan las políticas neo extractivistas. Frente a lo que está pasando, la lectura de este libro puede abrir corazones y conciencias. Y ya que el único camino para proteger a estos pueblos es el compromiso militante, activo y per- manente en defensa de sus derechos, su lectura no sólo se vuelve necesaria sino urgente, ya que hay que actuar ahora, antes de que sea demasiado tarde y los últimos pueblos libres desaparezcan irreparablemente de las profundidades de los bosques que han sido su hogar -

Past, Current and Future Contribution of Zooarchaeology to the Knowledge of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Cultures in South Caucasus Rémi Berthon

Past, Current and Future Contribution of Zooarchaeology to the Knowledge of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Cultures in South Caucasus Rémi Berthon To cite this version: Rémi Berthon. Past, Current and Future Contribution of Zooarchaeology to the Knowledge of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Cultures in South Caucasus. Studies in Caucasian Archaeology, Prof. Sergi Makalatia Gori Historical-Ethnographical Museum, 2014. hal-02136934 HAL Id: hal-02136934 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02136934 Submitted on 22 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PROF. SERGI MAKALATIA GORI HISTORICAL-ETHNOGRAPHICAL MUSEUM STUDIES IN CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY II TBILISI 2014 EDITORIAL BOARD: Dr. GIORGI MINDIASHVILI Dr. SANDRA HEINSCH (Editor in Chief) University of Innsbruck Georgian National Museum, Dr. GURAM KVIRKVELIA Otar Lordkipanidze Centre of Georgian National Museum, Archaeological Research Otar Lordkipanidze Centre of Dr. ARSEN BOBOKHYAN Archaeological Research (Editor of the Volume) BA. TAMAR MELADZE Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography Ilia State University Armenian Academy of Sciences MA. GIORGI KARELIDZE Yerevan State University Tbilisi State University Dr. WALTER KUNTNER MA. DIMITRI NARIMANISHVILI University of Innsbruck Kldekari Historical-Architechtural MA. THORSTEN RABSILBER Muzeum-Reserve Deutsches Bergbau Museum, Tbilisi State University Rühr-Universität Bochum MA. -

Unit V: Europe Physical: Europe Is Sometimes Described As A

Unit V: Europe Physical: Europe is sometimes described as a peninsula of peninsulas. A peninsula is a piece of land surrounded by water on three sides. Europe is a peninsula of the Eurasian supercontinent and is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and the Mediterranean, Black, and Caspian Seas to the south. Europes main peninsulas are the Iberian, Italian, and Balkan, located in southern Europe, and the Scandinavian and Jutland, located in northern Europe. The link between these peninsulas has made Europe a dominant economic, social, and cultural force throughout recorded history. Europe can be divided into four major physical regions, running from north to south: Western Uplands, North European Plain, Central Uplands, and Alpine Mountains. Western Uplands The Western Uplands, also known as the Northern Highlands, curve up the western edge of Europe and define the physical landscape of Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, and Denmark), Finland, Iceland, Scotland, Ireland, the Brittany region of France, Spain, and Portugal. The Western Uplands is defined by hard, ancient rock that was shaped by glaciation. Glaciation is the process of land being transformed by glaciers or ice sheets. As glaciers receded from the area, they left a number of distinct physical features, including abundant marshlands, lakes, and fjords. A fjord is a long and narrow inlet of the sea that is surrounded by high, rugged cliffs. Many of Europes fjords are located in Iceland and Scandinavia. North European Plain The North European Plain extends from the southern United Kingdom east to Russia. It includes parts of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Poland, the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), and Belarus.