A Reason to Hope…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Introduction Spices Constitute an Important Group of Agricultural Produce. They Are Used in Manufactures of Medicines, Cosmet

2 1. Introduction Spices constitute an important group of agricultural produce. They are used in manufactures of medicines, cosmetics, condiments, sweets, beverages and preservatives. Many value added products such as oils and oleoresins, curry powders, beverages, pickles etc. are also produced from them. Almost all countries in the world including those which do not produce consume spices or spice products. Thus they have an important place in international market. India is one of the largest producers and exporters of spices in the world. According to the Spices Board of India, there are fifty two varieties of spices cultivated in India. Pepper, cardamom, ginger, turmeric, nutmeg, clove, tamarind etc. are important among them. There is a total area of 2.3 million hectares of land under spices cultivation in India. Its annual production is estimated at 27 lakh tonnes valued at Rs. 1300 crores. More than 2.5 lakh farmers in rural areas of India are dependent on spices cultivation for livelihood and employment. The country has a share of about 44 per cent in quantity and 36 per cent in value in world spices trade. The state of Kerala, situated on the south western tip of India, is also noted for the cultivation of spices. A large variety of spices such as pepper, cardamom, turmeric, ginger, tamarind, clove, cinnamon, vanilla etc are grown in the state in most of its districts. Among the spices cultivated in Kerala, black pepper popularly known as ‘black gold’ and cardamom, the ‘queen of spices’ are the two major ones. Kerala accounted for 95 per cent of the total pepper production in India in the year 2009-10 and its share in the cardamom production of the country during this period was as high as 78 per cent. -

Sustainable Strategies of Small Scale Pepper Processing Industries – a Case Study in Wayanad, Kerala

International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET) Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2018, pp. 348–355, Article ID: IJMET_09_01_037 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJMET?Volume=9&Issue=1 ISSN Print: 0976-6340 and ISSN Online: 0976-6359 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed SUSTAINABLE STRATEGIES OF SMALL SCALE PEPPER PROCESSING INDUSTRIES – A CASE STUDY IN WAYANAD, KERALA Vijay K Rajan M.Com 4th Semester, Department of Management and Commerce, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Mysuru, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Karnataka, India Dr. S. RanjithKumar, Assistant Professor, Department of Management and Commerce, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Mysuru, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Karnataka, India ABSTRACT Agriculture plays a vital role in Indian economy, about 54.6% of the population is engaged in agriculture and allied pepper processing activities. Agriculture contributes 17% towards the nation’s Gross Value Added (GVA). Kerala has the 13th largest economy in India with the GDP of 7.48 lakh crore per annum. Although service industry is the predominant industry in Kerala, agriculture also having equal importance for the development of the state welfare as 12% of the GDP is derived from agriculture and allied activities. Natural rubber, coconut, tea, coffee, cashew and spices including cardamom, vanilla, cinnamon and nutmeg comprises a critical contribution to agricultural sector along with state produces 97% of pepper out of national output of India. District of Idukki and Wayanad are the two major pepper producers in Kerala. Idukki as the leading producer contributes 30,424 tons of pepper production from 43755 hectors. Wayanad contributes 3706 tons from8945 hectors. -

16 July 2020 To, Prof

WWW.LIVELAW.IN 16 July 2020 To, Prof. (Dr.) Ranbir Singh Chairperson & Vice-Chancellor Committee for Reforms in Criminal Laws Centre for Criminology and Victimology National Law University, Delhi Re: Concerns of Organisations and Individuals working on Child Rights regarding the Committee for Reforms in Criminal Laws Dear Prof (Dr.) Singh, As lawyers, activists, social workers, counsellors, academicians, psychologists, policy consultants and other professionals working on child rights across the country, we write this letter to you to put forth our strong objection to the constitution of the Committee for Reforms in Criminal Laws and the processes employed by it, including the rushed timeline proposed. We take issue on the following points:- 1. Lack of Diversity The constitution of the Committee lacks representation from various groups and sections of the society that are to be directly impacted by reforms in criminal laws of the country. There is a stark absence of women members, members from the LGBTQ community, members belonging to religious minorities, members belonging to the SC/ST groups, and persons with disabilities, to name a few. In your Public Notice dated 08.07.2020, you have made it clear that the structure of the Committee is the mandate of the MHA and is beyond your powers to intervene. However, we find that to be an easy way out on your part and we would like to see efforts on your part to engage with the MHA that constituted you, to make the structure of the Committee more inclusive. 2. Unconscionable Timing and Exclusionary Processes This process seems to have no justification in being rolled out in the manner in which it has in the midst of a global pandemic. -

Compendium of Best Practices on Anti Human Trafficking

Government of India COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS Acknowledgments ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ms. Ashita Mittal, Deputy Representative, UNODC, Regional Office for South Asia The Working Group of Project IND/ S16: Dr. Geeta Sekhon, Project Coordinator Ms. Swasti Rana, Project Associate Mr. Varghese John, Admin/ Finance Assistant UNODC is grateful to the team of HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi for compiling this document: Ms. Bharti Ali, Co-Director Ms. Geeta Menon, Consultant UNODC acknowledges the support of: Dr. P M Nair, IPS Mr. K Koshy, Director General, Bureau of Police Research and Development Ms. Manjula Krishnan, Economic Advisor, Ministry of Women and Child Development Mr. NS Kalsi, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs Ms. Sumita Mukherjee, Director, Ministry of Home Affairs All contributors whose names are mentioned in the list appended IX COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS © UNODC, 2008 Year of Publication: 2008 A publication of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Regional Office for South Asia EP 16/17, Chandragupta Marg Chanakyapuri New Delhi - 110 021 www.unodc.org/india Disclaimer This Compendium has been compiled by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights for Project IND/S16 of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for South Asia. The opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily represent the official policy of the Government of India or the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The designations used do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, frontiers or boundaries. -

Prerana Annual Report 2017-2018

PRERANA ANNUAL REPORT 2017-2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS SR. NO CONTENTS 1) About Prerana 2) The Governing Board 3) Prerana Programs 4) Communications at Prerana 5) Monitoring and Evaluation at Prerana 6) A Snapshot of the Year Gone by 7) Visitors to Prerana 8) Collaborations 9) Interns and Volunteers 10) Financials ABOUT PRERANA Prerana pioneered a path-breaking model to end intergenerational trafficking for prostitution. This model consists of 3 interventions – Night Care Centre (NCC), Education Support Program (ESP) and Institutional Placement Program (IPP). Prerana’s model is nationally and globally recognized as one that has a successful track record and one that is replicable in any red-light area setting. For over three decades, Prerana has been deploying the interventions in some of the largest red-light areas in Mumbai and Thane districts. Over the past few years Prerana has also taken into account the broader group of children-at-risk, whose vulnerabilities have a correlation with children from the red-light areas. In particular are our initiatives – Aarambh and Sanmaan that look at issues related to child sexual maltreatment and children in beggary. Our Mission: Prerana works to end intergenerational sex trafficking and to protect women and children from the threats of sexual and overall exploitation by defending their rights, restoring their dignity providing a safe environment, supporting their education and health and leading major advocacy efforts. Our Vision: We want to see a world where the innocence, weakness, and vulnerability of any human being is not exploited by others for commercial sexual exploitation and trafficking, the world is free of trade in human beings for sexual slavery, every child born leads a life full of options and enjoys a right to choose, a victim of commercial sexual exploitation and trafficking is not re-victimized but has a fair chance of social recognition and the society becomes more compassionate to the victims and intolerant of injustice. -

Life Skills Education Toolkit for Orphans and Vulnerable Children in India

Life Skills Education forforfor OrphansOrphansOrphans &&& VVVulnerableulnerableulnerable Toolkit ChildrenChildrenChildren in IndiaIndiain Family Health International (FHI) India Country Office In Collaboration with the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) With Funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) In July 2011, FHI became FHI 360. FHI 360 is a nonprofit human development organization dedicated to improving lives in lasting ways by advancing integrated, locally driven solutions. Our staff includes experts in health, education, nutrition, environment, economic development, civil society, gender, youth, research and technology – creating a unique mix of capabilities to address today’s interrelated development challenges. FHI 360 serves more than 60 countries, all 50 U.S. states and all U.S. territories. Visit us at www.fhi360.org. Acknowledgments Dr. Sonal Zaveri, FHI consultant led the process of putting together the Life Skills Education Toolkit. Anita Khemka took the photographs during visits to USAID/FHI projects. The National OVC Task Force including the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MoWCD), National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO), UNICEF and the India HIV/AIDS Alliance, reviewed the LSE Toolkit and gave valuable comments. The staff and children of 30 USAID/FHI projects contributed their ideas and time in the initial development and then pre-testing of the LSE toolkit. Suggested Citation Life Skills Education Toolkit for Orphans & Vulnerable Children in India, India – (October 2007) ISBN 1-933702-19-2 Any parts of this toolkit may be photocopied or adapted to meet local needs without permission from USAID/FHI or IMPACT, provided that the source is acknowledged, the parts copied are distributed free of cost and credit is given to USAID/FHI/IMPACT. -

CSR Report 2008

Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2008 Our Goals for 2009 Building Social Capital CSR Report 2008 To introduce the Sustainability Management System in the growth regions Deutsche Bank regards Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as an investment in Asia, South America, and the Middle East society and in its own future. Our goal as a responsible corporate citizen is to create social capital. We leverage our core competencies in five areas of activity. To continue pressing ahead with climate-friendly activities, with the aim of Our Identity. Sustainability: An integral part of all Deutsche Bank activities – in our core business making all business processes totally CO2-neutral from 2013 onwards We are a leading global investment bank with a and beyond – is being responsible to our shareholders, clients, employees, society, To expand the educational initiatives for intercultural understanding, with strong and profitable private clients franchise. Our and the environment. the aim of increasing equality of opportunity and promoting integration businesses are mutually reinforcing. A leader in Germany and Europe, we are powerful and growing Corporate Volunteering: A growing number of our employees are committed To step up our commitment to helping children and AIDS orphans in in North America, Asia and key emerging markets. to civic leadership and responsibility – with the support and encouragement of developing and emerging countries and to strengthen our collaboration Deutsche Bank. with SOS Children‘s Villages in our German home market Our Mission. We compete to be the leading global provider of Social Investments: We create opportunities for people and communities. We help financial solutions for demanding clients creating To increase the Corporate Volunteering rate still further and extend paid Building Social Capital them overcome unemployment and poverty, and shape their own futures. -

Who Trusts Local Human Rights Organizations? Evidence from Three World Regions

HUMAN RIGHTS QUARTERLY Who Trusts Local Human Rights Organizations? Evidence from Three World Regions James Ron* & David Crow** ABSTRACT Local human rights organizations (LHROs) are crucial allies in international efforts to promote human rights. Without support from organized civil society, efforts by transnational human rights reformers would have little effect. Despite their importance, we have little systematic information on the correlates of public trust in LHROs. To fill this gap, we conducted key informant interviews with 233 human rights workers from sixty countries, and then administered a new Human Rights Perceptions Poll to represen- tative public samples in Mexico (n = 2,400), Morocco (n = 1,100), India (n = 1,680), and Colombia (n = 1,699). Our data reveal that popular trust in local rights groups is consistently associated with greater respondent familiarity with the rights discourse, actors, and organizations, along with greater skepticism toward state institutions and agents. The evidence fails to provide consistent, strong support for other commonly held expectations, however, including those about the effects of foreign funding, socioeconomic status, and transnational connections. I. INTRODUCTION Domestic civil society is a crucial player in international efforts to promote human rights. Without organized pressure “from below,” governments will rarely translate international human rights laws and commitments into mean- * James Ron holds the Harold E. Stassen Chair for International Affairs at the Humphrey School of Public -

Spice-Report.Pdf

TITLE Business Case for Spices Production & Processing in Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Uttarakhand YEAR April, 2018 AUTHORS YES BANK and IDH No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by photo, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without COPYRIGHT the written permission of YES BANK Ltd. & IDH. This report is the publication of YES BANK Limited (“YES BANK”) and IDH so YES BANK and IDH have editorial control over the content, including opinions, advice, statements, services, offers etc. that is represented in this report. However, YES BANK, IDH will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the reader’s reliance on information obtained through this report. This report may contain third party contents and third-party resources. YES BANK and/ or IDH take no responsibility for third party content, advertisements or third party applications that are printed on or through this report, nor does it take any responsibility for the goods or services provided by its advertisers or for any error, omission, deletion, defect, theft or destruction or unauthorized access to, or alteration of, any user communication. The contents are provided for your reference and information purposes only, and are not intended to substitute professional advice in relation to the subject matter. The reader/buyer understands that except for the information, products and services clearly identified as being supplied by YES BANK and IDH, YES BANK and IDH do not operate, control or endorse any other information, products, or services appearing in the report in any way. All other information, products and services offered through the report are offered by third parties, which are not affiliated in any manner to YES BANK or IDH. -

Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health & HIV/AIDS Among Young

Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health & HIV/AIDS among Young People Compendium of Institutions in India For further information please contact: Adolescent Health and Development Unit Department of Family and Community Health or HIV/AIDS Unit Department of Communicable Diseases World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia World Health House, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002 Email: [email protected]; Weblink: http://searo.who.int 2006 Produced under WHO – UNFPA Global Strategic Partnership Programme (SPP) Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health & HIV/AIDS among Young People Compendium of Institutions in India 2006 © World Health Organization 2007 This health information product is intended for a restricted audience only. It may not be reviewed, abstracted, quoted, reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated or adapted, in part or in whole, in any form or by any means. The World Health Organization has no authority to grant any form of recognition or accreditation to institutions or organizations listed in this health information product. Such a procedure remains the exclusive prerogative of the national government concerned. Consequently, no institution listed in this health information product is recognized or accredited, or its training programme endorsed by the World Health Organization. The names and address have been compiled from data received from experts in the Member State concerned. The Organization cannot therefore accept responsibility for inclusion or omission of the name of any institution. The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this health information product is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. -

Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2006

Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2006 Provisional January 5, 2007 ASER2006 - Rural Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) Date of publication: January 5, 2007 Cover: ‘Mother and child in Kamrup’, a member of the ASER team took this picture in Assam. Back cover: ‘Logging into education’, a member of the ASER team took this picture in Himachal Pradesh. Other photos: All photos taken by volunteers as they visited villages. Also available on CD. For more information: [email protected] Price: Students: Rs. 100 Other individuals: Rs. 200 Institutions: Rs. 500 Outside India: USD 50.00/GBP 25.00 Layout by: Trimiti Services, Mumbai Printed by: Published by: Pratham Resource Center Mumbai office: Ground Floor, YB Chavan Center, Gen. J. Bhosale Marg, Nariman Point, Mumbai, 400 021. Phone: 91-22-22886975, 91-22-23851405 New Delhi office: A1/7, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi, 110 029. Phone: 91-11-26716083/84 Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2006 Provisional January 5, 2007 INDIA RURAL Districtwise distribution of % out-of-school children aged 6-14 % out of school children aged 6-14 Maps may not be accurate or to scale. These are mere representations. ii ASER 2006 INDIA RURAL Districtwise distribution of % Std I and II children who can read letters or more % Std I and II children who can read letters or more Maps may not be accurate or to scale. These are mere representations. ASER 2006 iii They reached the remotest villages of India Sr. No. Andaman & Nicobar Islands 72 Nav Nirman College, Dodamarg Jharkhand 1 Nehru Yuva Kendra Sangathan -

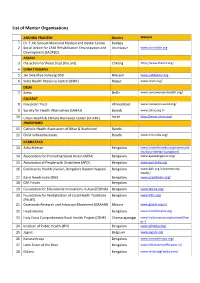

Mentors List

List of Mentor Organisations ANDHRA PRADESH District Website 1 Dr. T. M. Samuel Memorial Medical and Dental Centre Kadapa 2 Social Action for Child Rehabilitation Emancipation and Anantapur www.sacredcbr.org Development (SACRED) ASSAM 3 the action northeast trust (the ant) Chirang http://www.theant.org/ 4 CHHATTISGARH 5 Jan Swasthya Sahayog (JSS) Bilaspur www.jssbilaspur.org 6 State Health Resource Centre (SHRC) Raipur www.shsrc.org/ DELHI 7 Sama Delhi www.samawomenshealth.org/ GUJARAT 8 Navsarjan Trust Ahmedabad www.navsarjan-surat.org/ 9 Society for Health Alternatives (SAHAJ) Baroda www.sahaj.org.in 10 Urban Health & Climate Resilience Center (UHCRC) Surat http://www.uhcrc.org/ JHARKHAND 11 Catholic Health Association of Bihar & Jharkhand Ranchi 12 Child in Need Institute Ranchi www.cini-india.org/ KARNATAKA 13 Asha Niketan Bengaluru www.larchefmrindia.org/communit ies/asha-niketan-bangalore/ 14 Association for Promoting Social Action (APSA) Bengaluru www.apsabangalore.org/ 15 Association of People with Disabilities (APD) Bengaluru www.apd-india.org 16 Community Health Division, Bangalore Baptist Hospital Bengaluru www.bbh.org.in/community- health/ 17 Basic Needs India (BNI) Bengaluru www.prajadwani.org/ 18 CBR Forum Bengaluru 19 Foundation for Educational Innovations in Asia (FEDINA) Bengaluru www.fedina.org/ 20 Foundation for Revitalization of Local Health Traditions Bengaluru www.frlht.org/ (FRLHT) 21 Grassroots Research and Advocacy Movement (GRAAM) Mysore www.graam.org.in/ 22 Headstreams Bengaluru www.headstreams.org 23 Holy Cross Comprehensive Rural Health Project (CRHP) Chamarajanagar www.holycrosscip.org/content/han ur-1 24 Institute of Public Health (IPH) Bengaluru www.iphindia.org/ 25 Jagruti Belgaum www.jagruti.org 26 Karunashraya Bengaluru www.karunashraya.org/ 27 Little Sister of the Poor Bengaluru www.littlesistersofthepoor.in/ 28 Milana Bengaluru www.milanabgl.webs.com/ 29 Myrada Gulbarga www.myrada.org/myrada/ 30 Department of Community Medicine, M.S.