Cache Pilfering in a Granivore Guild: Implications for Reintroduction Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

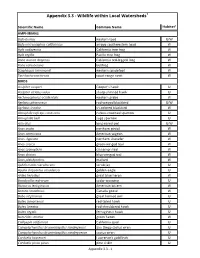

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife Within Local Watersheds1

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife within Local Watersheds1 2 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat AMPHIBIANS Bufo boreas western toad U/W Bufo microscaphus californicus arroyo southwestern toad W Hyla cadaverina California tree frog W Hyla regilla Pacific tree frog W Rana aurora draytonii California red-legged frog W Rana catesbeiana bullfrog W Scaphiopus hammondi western spadefoot W Taricha torosa torosa coast range newt W BIRDS Accipiter cooperi Cooper's hawk U Accipiter striatus velox sharp-shinned hawk U Aechmorphorus occidentalis western grebe W Agelaius phoeniceus red-winged blackbird U/W Agelaius tricolor tri-colored blackbird W Aimophila ruficeps canescens rufous-crowned sparrow U Aimophilia belli sage sparrow U Aiso otus long-eared owl U/W Anas acuta northern pintail W Anas americana American wigeon W Anas clypeata northern shoveler W Anas crecca green-winged teal W Anas cyanoptera cinnamon teal W Anas discors blue-winged teal W Anas platrhynchos mallard W Aphelocoma coerulescens scrub jay U Aquila chrysaetos canadensis golden eagle U Ardea herodius great blue heron W Bombycilla cedrorum cedar waxwing U Botaurus lentiginosus American bittern W Branta canadensis Canada goose W Bubo virginianus great horned owl U Buteo jamaicensis red-tailed hawk U Buteo lineatus red-shouldered hawk U Buteo regalis ferruginous hawk U Butorides striatus green heron W Callipepla californica California quail U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegensis San Diego cactus wren U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegoense cactus wren U Carduelis lawrencei Lawrence's -

Body Size, Not Phylogenetic Relationship Or Residency, Drives Interspecific Dominance in a Little Pocket Mouse Community

Animal Behaviour 137 (2018) 197e204 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Body size, not phylogenetic relationship or residency, drives interspecific dominance in a little pocket mouse community * Rachel Y. Chock a, , Debra M. Shier a, b, Gregory F. Grether a a Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, U.S.A. b Recovery Ecology, San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Escondido, CA, U.S.A. article info The role of interspecific aggression in structuring ecological communities can be important to consider Article history: when reintroducing endangered species to areas of their historic range that are occupied by competitors. Received 6 September 2017 We sought to determine which species is the most serious interference competitor of the endangered Initial acceptance 6 November 2017 Pacific pocket mouse, Perognathus longimembris pacificus, and more generally, whether interspecific Final acceptance 1 December 2017 aggression in rodents is predicted by body size, residency status or phylogenetic relatedness. We carried out simulated territory intrusion experiments between P. longimembris and four sympatric species of MS. number: A17-00719 rodents (Chaetodipus fallax, Dipodomys simulans, Peromyscus maniculatus, Reithrodontomys megalotis)ina field enclosure in southern California sage scrub habitat. We found that body size asymmetries strongly Keywords: predicted dominance, regardless of phylogenetic relatedness or the residency status of the individuals. aggression The largest species, D. simulans, was the most dominant while the smallest species, R. megalotis, was the dominance least dominant to P. longimembris. Furthermore, P. longimembris actively avoided encounters with all interference competition Perognathus longimembris species, except R. -

Draft Environmental Assessment of Marine Geophysical Surveys by the R/V Marcus G. Langseth for the Southern California Collaborative Offshore Geophysical Survey

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF MARINE GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS BY THE R/V MARCUS G. LANGSETH FOR THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA COLLABORATIVE OFFSHORE GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY Submitted to: National Science Foundation Division of Ocean Sciences 4201 Wilson Blvd., Suite 725 Arlington, VA 22230 Submitted by: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD 8675 Discovery Way La Jolla, CA 92023 Contact: Professor Neal Driscoll 858.822.5026; [email protected] Prepared by: Padre Associates, Inc. 5290 Overpass Road, Suite 217 Goleta, CA 93113 June 2012 Southern California Collaborative Offshore Geophysical Survey (SCCOGS) Environmental Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PURPOSE AND NEED ................................................................................................... 1 2.0 ALTERNATIVES INCLUDING PROPOSED ACTION ...................................................... 6 2.1 PROPOSED ACTION ......................................................................................... 6 2.2 PROJECT LOCATION ........................................................................................ 6 2.3 PROJECT ACTIVITIES ....................................................................................... 6 2.3.1 Mobilization and Demobilization .............................................................. 9 2.3.2 Offshore Survey Operations .................................................................... 9 2.3.2.1 Survey Vessel Specifications ..................................................... 10 2.3.2.2 Air Gun Description ................................................................... -

Recovery Research for the Endangered Pacific Pocket Mouse: an Overview of Collaborative Studies1

Recovery Research for the Endangered Pacific Pocket Mouse: An Overview of Collaborative Studies1 Wayne D. Spencer2 Abstract The critically endangered Pacific pocket mouse (Perognathus longimembris pacificus), feared extinct for over 20 years, was “rediscovered” in 1993 and is now documented at four sites in Orange and San Diego Counties, California. Only one of these sites is considered large enough to be potentially self-sustaining without active intervention. In 1998, I gathered a team of biologists to initiate several research tasks in support of recovery planning for the species. The PPM Studies Team quickly determined that species recovery would require active trans- locations or reintroductions to establish new populations, but that we knew too little about the biology of P. l. pacificus and the availability of translocation receiver sites to design such a program. Recovery research from 1998 to 2000 therefore focused on (1) a systematic search for potential translocation receiver sites; (2) laboratory and field studies on non-listed, surro- gate subspecies (P. l. longimembris and P. l. bangsi) to gain biological insights and perfect study methods; (3) studies on the historic and extant genetic diversity of P. l. pacificus; and (4) experimental habitat manipulations to increase P. l. pacificus populations. Using existing geographic information system (GIS) data, we identified sites throughout the historic range that might have appropriate soils and vegetation to support translocated P. l. pacificus. Re- connaissance surveys of habitat value were completed in all large areas of potential habitat identified by the model. Those sites having the highest habitat potential are being studied with more detailed and quantitative field analyses. -

PACIFIC POCKET MOUSE Perognathus Longimembris Pacificus

Terrestrial Mammal Species of Special Concern in California, Bolster, B.C., Ed., 1998 113 Pacific pocket mouse, Perognathus longimembris pacificus Philip V. Brylski Description: This is a small heteromyid rodent, averaging about 113 mm TL, and weighing from 8 to 10 g. Silky pocket mice, including the Pacific pocket mouse, are distinguished from species of Chaetodipus by the absence of spiny hairs in the dorsal pelage and the absence of a distinct crest on the tail. There is usually a small white spot at the anterior base of the ear, and an indistinct larger buff spot behind the ear. The pelage is buff above and white below. Many of the dorsal hairs are black-tipped, giving the pelage a "salt and pepper" appearance typical of the species. The Pacific pocket mouse is the darkest of the Perognathus longimembris subspecies. Pelage color shows substantial age-related and seasonal variation; the pelage is darkest in juveniles, and relatively dark in newly-molted adults. The pelage in all age groups lightens gradually between molts. Like all heteromyids, there is a buff-colored lateral line. The plantar surface of the hindfeet is naked or lightly haired, and the lateral hairs of the hind toes project anteriorly and laterally, resulting in a "fringed-toed" effect, which may enhance locomotor efficiency on sandy substrates (Brylski 1993). Taxonomic Remarks: The Pacific pocket mouse is one of eight recognized subspecies of the little pocket mouse (P. longimembris) in California (Hall 1981; Williams et al. 1993). As a species, the little pocket mouse shows considerable geographic and non-geographic variation in pelage color. -

Captive Breeding, Anti-Predator Behavior and Reintroduction of the Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognathus Longimembris Pacificus)

State of California Natural Resources Agency Department of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Branch Captive Breeding, Anti-Predator Behavior and Reintroduction of the Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognathus longimembris pacificus) 2012-2014 By Dr. Debra Shier _______________________________________________________ Nongame Wildlife Program, 2014-03 Final Report To State of California Department of Fish and Wildlife South Coast Region 3883 Ruffin Road San Diego, CA 92123 Captive Breeding, Anti-Predator Behavior and Reintroduction of the Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognathus longimembris pacificus) For the period June 15, 2012 – June 14, 2014 Dr. Debra M. Shier San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research Division of Applied Animal Ecology Escondido, CA 92027 Prepared June 11, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 7 Objectives .................................................................................................................................... 8 PERSONNEL ................................................................................................................................. 8 CAPTURING FOUNDERS ............................................................................................................ 9 Methods ....................................................................................................................................... 9 General trapping protocol ....................................................................................................... -

SERDP Project ER18-1653

FINAL REPORT Approach for Assessing PFAS Risk to Threatened and Endangered Species SERDP Project ER18-1653 MARCH 2020 Craig Divine, Ph.D. Jean Zodrow, Ph.D. Meredith Frenchmeyer Katie Dally Erin Osborn, Ph.D. Paul Anderson, Ph.D. Arcadis US Inc. Distribution Statement A Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. -

The Journal of Wildlife Management, 83(7)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship - University of California UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Cache pilfering in a granivore guild: Implications for reintroduction management Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1244z0r9 Journal The Journal of Wildlife Management, 83(7) ISSN 0022-541X Authors Chock, Rachel Y Grether, Gregory F Shier, Debra M Publication Date 2019-09-01 DOI 10.1002/jwmg.21736 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Journal of Wildlife Management 83(7):1607–1616; 2019; DOI: 10.1002/jwmg.21736 Note Cache Pilfering in a Granivore Guild: Implications for Reintroduction Management RACHEL Y. CHOCK ,1,2 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of California Los Angeles, 612 Charles E. Young Drive E, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA GREGORY F. GRETHER, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of California Los Angeles, 612 Charles E. Young Drive E, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA DEBRA M. SHIER,3 Recovery Ecology, San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, 15600 San Pasqual Valley Road, Escondido, CA 92027, USA ABSTRACT Reintroduction programs that release endangered species back into areas from which they have been extirpated rarely take competitive interactions between species into account. The endangered Pacific pocket mouse (Perognathus longimembris pacificus) is being reintroduced to parts of its former range where multiple species of native rodents have overlapping diets. The granivorous species in this foraging guild compete for seeds exploitatively and through direct interference interactions, and pocket mice are the smallest and least dominant species in the guild. -

~ Ilk; Family Heteromyidae, Which Consists of Pacificus and P

49752 Federal Register / Vol. 59, No. 188 I Thursday, September29, 1994 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR one of 19 recognized subspecies of the pocket mouse as a distinct species, he little pocket mouse (Perognathus subsequently concluded that P. Fish and Wildlife Service longimembris) (Hall 1981). This species pacificus represented two subspecies of is one of the smallestmembers of the the little pocket mouse, P. Iongirnembris 5OCFRPart17 ~ iLk; family Heteromyidae, which consists of pacificus and P. 1. cantwelli, after RIN 1018—AC39 spiny pocketmice (Heteroniys and examining additional specimens (von Liomys), pocket mice (Perognathus and Bloeker 1932). Subsequent toa Endangered and Threatened Wildlife Chaetodipus), kangaroo rats biometric analysis of 331 specimens of and Plants; Determination of (Dipodomys), and kangaroo mice the little pocketmouse, Huey (1939) Endangered Status for the Pacific (Microdipodops). Virtually all (if not all) recognized P. 1. pacificus tobe inclusive Pocket Mouse members of this family are nocturnal, of the two subspecies described by von granivorous and have external, deep, Bloeker (1932). Subsequent taxonomic AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, fur-lined cheek pouches (Ingles 1965; treatments (e.g., Hall 1981; Williams et Interior. Dr. P. Brylski, consulting mammalogist, al. 1993) haveretained the Pacific ACTION: Final rule. pers. comm., 1993). pocket mouse as a distinct subspecies. Perognathus longiniembris ranges in Although a taxonomic review of P. SUMMARY: The Fish and Wildlife Service size from about 110 to 151 millimeters longiniembris may be appropriate, the (Service) determines the Pacific pocket (mm) (4.3 to 5.9 inches) from nose to tip Pacific pocket mouse has been mouse (Perognath us Iongimembris of tail (Hall 1981) and weighs 7 to 9 pacificus) to be an endangered species described as distinct from related forms grams (1/4 to ½oz.) (Burt and (Dr. -

Recovery Plan for the Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognathus Longimembris Pacificus)* Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognath Us Iongimembris Pacificus)

Recovery Plan for the Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognathus longimembris pacificus)* Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognath us iongimembris pacificus) Recovery Plan Published by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Region 1 Portland, Oregon Prepared by Phillip Bryiski, Ph.D. Loren Hays Jon Avery Approved: Region 1, U.S. ish and Wildlife Service Date: I & DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate actions required to recover and/or protect listed species. We (the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) publish plans. Sometimes the plans are prepared with the assistance ofrecovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and other affected and interested parties. Recovery teams serve as independent advisors to us. Plans are reviewed by the public and submitted to additional peer review before they are adopted by us. Objectives of the plan will be attained and any necessary funds made available, subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not obligate other parties to undertake specific tasks and may not represent the views nor the official positions or approval ofany individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than us. They represent our official position only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. LITERATURE CITATION: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1998. Pacific Pocket Mouse (Perognathus longimembris pac~ficus) Recovery Plan. Portland, OR. ll2pp. Additional copies may be purchased from: Fish and Wildlife Reference Service 5430 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 110 Bethesda, Maryland 208 14-2142 301/492-6403 or 1-800-582-3421 FAX: 301/564-4059 The fee for the Plan varies depending on the number ofpages ofthe Plan. -

Species-Specific Conservation Analyses and Conditions for Coverage

Section 4 Tricolored Blackbird Tricolored Blackbird Agelaius tricolor USFWS: Federal Species of Concern (former Category 2 Candidate) CDFG: Species of Special Concern MHCP: Obligate Wetlands Species Conservation Goals Ensure persistence of the tricolored blackbird in the plan area. Enhance habitat quality and increase the number of breeding colonies and total population size in the plan area. Contribute to regional population viability and species recovery. Conservation Strategy Conserve existing tricolored blackbird wetlands breeding habitat and grasslands foraging habitat, and tricolored blackbird point localities in the MHCP. Include within the open space preserve system existing populations of tricolored blackbird and other potential habitat. Provide appropriate upland buffers (minimum of 50 feet and up to 100 feet wide where possible) for all known populations. Protect potential grasslands foraging habitat in vicinity of breeding habitat. Facilitate coordination of local, state, and federal conservation and management actions for this species. Summary of Findings and Conditions for Coverage Findings. [TBD by wildlife agencies in the Biological Opinion after MHCP public review.] Achievement of Conservation Goals. Current levels of conservation expected under the current MHCP FPA and guidelines do not meet the conservation goals for this species. Few large grassland areas or agricultural areas will be conserved near potential nesting habitats. Only about 31% of the extant grasslands in the study area are expected to be conserved, and the plan does not protect agricultural lands from development. Critical grassland areas near marsh habitats are partially conserved and will become further fragmented. Conditions. Not applicable. Background Distribution, Abundance, and Trends. The tricolored blackbird distribution is centered in the Sacramento/San Joaquin valleys of California. -

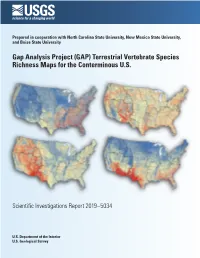

Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S

Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Mosaic of amphibian, bird, mammal, and reptile species richness maps derived from species’ habitat distribution models of the conterminous United States. Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. By Kevin J. Gergely, Kenneth G. Boykin, Alexa J. McKerrow, Matthew J. Rubino, Nathan M. Tarr, and Steven G. Williams Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text.