Open Society – Georgia Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Cyber Deterrence

STRATEGIC CYBER DETERRENCE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy By CHRISTOPHER FITZGERALD WRENN In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy JULY 2012 Dissertation Committee Professor Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr., Chair Professor Antonia H. Chayes Professor William C. Martel UMI Number: 3539954 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3539954 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 COLONEL CHRISTOPHER F. WRENN (CHRIS) 26 Pearl Street, Medford, MA, 02155 · 325-864-1515 · [email protected] Education Tufts University, the Fletcher School Medford, MA PhD Candidate, 2009–present Pursuing doctoral study in International Relations. Research topic: Deterrence, cyber deterrence Tufts University, the Fletcher School Medford, MA National Defense Fellow, 2006–2007 Pursued a course of study in areas central to United States national security: nuclear proliferation, counterproliferation, terrorism, crisis management, homeland security, and intelligence. Research topic: Global Salafi jihadist insurgency Air University, Air Command and Staff College Montgomery, AL Master of Military Operational Art and Science, June 2000 Completed a course of study with focus on national security and military studies. -

2018-2019 წლების ანგარიში/Annual Report

რელიგიის საკითხთა STATE AGENCY FOR სახელმწიფო სააგენტო RELIGIOUS ISSUES 2018-2019 წლების ანგარიში/ANNUAL REPORT 2020 თბილისი TBILISI წინამდებარე გამოცემაში წარმოდგენილია რელიგიის საკითხთა სახელმწიფო სააგე- ნტოს მიერ 2018-2019 წლებში გაწეული საქმიანობის ანგარიში, რომელიც მოიცავს ქვეყა- ნაში რელიგიის თავისუფლების კუთხით არსებული ვითარების ანალიზს და იმ ძირითად ღონისძიებებს, რასაც სააგენტო ქვეყანაში რელიგიის თავისუფლების, შემწყნარებლური გარემოს განმტკიცებისთვის ახორციელებს. ანგარიშში განსაკუთრებული ყურადღებაა გამახვილებული საქართველოს ოკუპირებულ ტერიტორიებზე, სადაც ნადგურდება ქართული ეკლესია-მონასტრები და უხეშად ირღვე- ვა მკვიდრი მოსახლეობის უფლებები რელიგიის, გამოხატვისა და გადაადგილების თავი- სუფლების კუთხით. ანგარიშში მოცემულია ინფორმაცია სააგენტოს საქმიანობაზე „ადამიანის უფლებების დაცვის სამთავრობო სამოქმედო გეგმის“ ფარგლებში, ასევე ასახულია სახელმწიფოს მხრი- დან რელიგიური ორგანიზაციებისათვის გაწეული ფინანსური თუ სხვა სახის დახმარება და განხორციელებული პროექტები. This edition presents a report on the activities carried out by the State Agency for Religious Is- sues in 2018-2019, including analysis of the situation in the country regarding freedom of religion and those main events that the Agency is conducting to promote freedom of religion and a tolerant environment. In the report, particular attention is payed to the occupied territories of Georgia, where Georgian churches and monasteries are destroyed and the rights of indigenous peoples are severely violated in terms of freedom of religion, expression and movement. The report provides information on the Agency's activities within the framework of the “Action Plan of the Government of Georgia on the Protection of Human Rights”, as well as financial or other assistance provided by the state to religious organizations and projects implemented. რელიგიის საკითხთა სახელმწიფო სააგენტო 2018-2019 წლების ანგარიში სარჩევი 1. რელიგიისა და რწმენის თავისუფლება ოკუპირებულ ტერიტორიებზე ........................ 6 1.1. -

PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL of KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES N O 27 — 2017 2

1 PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL OF KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES N o 27 — 2017 2 E DITOR- IN-CHIEF David KOLBAIA S ECRETARY Sophia J V A N I A EDITORIAL C OMMITTEE Jan M A L I C K I, Wojciech M A T E R S K I, Henryk P A P R O C K I I NTERNATIONAL A DVISORY B OARD Zaza A L E K S I D Z E, Professor, National Center of Manuscripts, Tbilisi Alejandro B A R R A L – I G L E S I A S, Professor Emeritus, Cathedral Museum Santiago de Compostela Jan B R A U N (†), Professor Emeritus, University of Warsaw Andrzej F U R I E R, Professor, Universitet of Szczecin Metropolitan A N D R E W (G V A Z A V A) of Gori and Ateni Eparchy Gocha J A P A R I D Z E, Professor, Tbilisi State University Stanis³aw L I S Z E W S K I, Professor, University of Lodz Mariam L O R T K I P A N I D Z E, Professor Emerita, Tbilisi State University Guram L O R T K I P A N I D Z E, Professor Emeritus, Tbilisi State University Marek M ¥ D Z I K (†), Professor, Maria Curie-Sk³odowska University, Lublin Tamila M G A L O B L I S H V I L I, Professor, National Centre of Manuscripts, Tbilisi Lech M R Ó Z, Professor, University of Warsaw Bernard OUTTIER, Professor, University of Geneve Andrzej P I S O W I C Z, Professor, Jagiellonian University, Cracow Annegret P L O N T K E - L U E N I N G, Professor, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena Tadeusz Ś W I Ę T O C H O W S K I (†), Professor, Columbia University, New York Sophia V A S H A L O M I D Z E, Professor, Martin-Luther-Univerity, Halle-Wittenberg Andrzej W O Ź N I A K, Professor, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 3 PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL OF KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES No 27 — 2017 (Published since 1991) CENTRE FOR EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES FACULTY OF ORIENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW WARSAW 2017 4 Cover: St. -

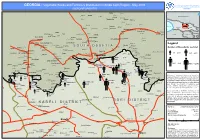

Map Sub-Title

Vegetable Seeds and FertilizersM Distributionap Sub-T init Shidale Kartli Region - May 2009 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GEORGIA - MAP TITLE - Emergency Rehabilitation Coordination Unit Da(OSRO/GEO/803/ITA)te (dd mmm yyyy) GEORGIA ! Tsia!ra ! !Klarsi Klarsi Andaisi Kintsia ! ! ! Zalda ! RUSSIAN FEDERATION Mipareti ! Maraleti ! Sveri ! ! ! Tskaltsminda Sheleuri !Saboloke !Gvria Marmazeti Eltura ! ! !Kemerti ! Didkhevi Black Sea ! Ortevi ! GEORGIA Tbilisi Kekhvi Tliakana ! ! \ ! Dzartsemi Guchmasta ! ! Marmazeti Khoshuri ! Satskheneti ! ! ! ! Beloti Jojiani Khaduriantkari ! Zemo Zoknari Rustavi ! ! Kurta Snekvi AZERBAIJAN ! Vaneti ! Chachinagi Dzari Zemo Monasteri ! TURKEY ! ! ! Kvemo Zoknari Mamita ! ARMENIA Brili ! ! Brili Zemo Kornisi ! Zemo Tsorbisi ! ! Mebrune ! !Zemo Achabeti ! ! Dmenisi Snekvi Kokhati ! ! Zemo Dodoti Dampaleti Zemo Sarabuk!i Tsorbisi ! ! ! ! Charebi Kvemo Achabeti ! Vakhtana ! Kheiti ! Kverneti ! Didi Tsitskhiata! Patara TsikhiataBekmeri Kvemo Dodoti ! ! ! ! Satakhari ! Legend Bekmari Zemo Ambreti Didi Tsikhiata ! ! !Dmenisi ! Kvasatal!i Naniauri ! ! Eredvi ! Lisa Zemo Ambreti SS OO UU TT HH OO SS SS EE TT II AA ! ! ! Ksuisi assisted Khodabula ! Number of Households !Mukhauri ! !Nagutni Zardiantkari ! Berula ! !Kusireti !Malda !Tibilaani !Argvitsi Teregvani !Galaunta ! !Khelchua Zem! o Prisi Zemo D!zagina Kvemo Nanadakevi ! Disevi ! ! Pichvigvina Zemo Dzagvina ! ! 01 - 250 ! ! Kroz! a Akhalsheni ! Tbeti Arbo ! 251 - 500 ! Arkneti ! Tamarasheni ! Mereti Kulbiti Sadjvare ! ! ! Koshka Beridjvari -

ICC-01/15 13 October 2015 Original

ICC-01/15-4 13-10-2015 1/160 EO PT Original: English No.: ICC-01/15 Date: 13 October 2015 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Joyce Aluoch, Presiding Judge Judge Cuno Tarfusser Judge Péter Kovács SITUATION IN GEORGIA Public Document with Confidential, EX PARTE, Annexes A,B, C, D.2, E.3, E.7, E.9, F H and Public Annexes 1, D.1, E.1, E.2, E.4, E.5, E.6, E.8,G ,I, J Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15 Source: Office of the Prosecutor ICC-01/15 1/160 13 October 2015 ICC-01/15-4 13-10-2015 2/160 EO PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Mrs Fatou Bensouda Mr James Stewart Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Defence Support Section Mr Herman von Hebel Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section No. ICC-01/15 2/160 13 October 2015 ICC-01/15-4 13-10-2015 3/160 EO PT Table of Contents with Confidential, EX PARTE, Annexes C, D,E.3, E.7,E.9 H and Public Annexes, A, B,D, E.1, E.2, E.4, E.5, E.6, E.8, F,G,I,J................................................................................................1 Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15 ....................................1 I. -

Pdf | 406.42 Kb

! GEORGIA: Newly installed cattle water troughs in Shida Kartli region ! ! Geri ! !Tsiara Klarsi ! Klarsi Andaisi Kintsia ! ! ! Zalda RUSSIAN FEDERATION ! !Mipareti Maraleti Sveri ! I ! Tskaltsminda ! Sheleuri ! Saboloke V ! H Gvria K ! A AG Marmazeti Eltura I M Didkhevi ! ! L Kemerti ! O ! A SA Didkhevi V ! Ortevi R L ! A E Kekhvi Tliakana T Black Sea T'bilisi ! Dzartsemi ! Guchmasta A T ! ! Marmazeti Khoshuri ! ! ! P ! Beloti F ! Tsilori Satskheneti Atsriskhevi ! !\ R Jojiani ! ! ! O Rustavi ! Zemo Zoknari ! N Kurta Snekvi Chachinagi Dzari Zemo Monasteri ! Vaneti ! ! ! ! ! Kvemo Zoknari E Brili Mamita ! ! ! Isroliskhevi AZERBAIJAN !Kvemo Monasteri ! !Brili Zemo Tsorbisi !Zemo Kornisi ! ARMENIA ! Mebrune Zemo Achabeti Kornisi ! ! ! ! Snekvi ! Zemo Dodoti Dampaleti Zemo SarabukiKokhat!i ! Tsorbisi ! ! ! ! TURKEY ! Charebi ! Akhalisa Vakhtana ! Kheiti Benderi ! ! Kverneti ! ! Zemo Vilda P! atara TsikhiataBekmeri Kvemo Dodoti ! NA ! ! ! ! Satakhari REB ULA ! Bekmari Zemo Ambreti Kverne!ti ! Sabatsminda Kvemo Vilda Didi Tsikhiata! ! ! Dmenisi ! ! Kvasatali!Grubela Grubela ! ! ! ! Eredvi ! !Lisa Tormanauli ! ! Ksuisi Legend Khodabula ! Zemo Ambreti ! ! ! ! Berula !Zardiantkari Kusireti ! ! Chaliasubani Malda Tibilaani Arkinareti ! Elevation ! ! Argvitsi ! Teregvani ! Galaunta ! Khelchua ! Zemo Prisi ! ! ! Pirsi Kvemo Nanadakevi Tbeti ! Disevi ! ! ! ! Water trough location m ! ! Zemo Mokhisi ! ! ! Kroza Tbeti Arbo ! !Akhalsheni Arkneti ! Tamarasheni ! ! Mereti ! Sadjvare ! ! ! K ! Khodi Beridjvari Koshka ! -27 - 0 Chrdileti Tskhinvali ! ! -

GEORGIA: UN Security Phases 23 Dec 2008

South Ossetia & Area Adjacent to South Ossetia GEORGIA: UN Security Phases 23 Dec 2008 K K N U Gveleti N ! U ShoviCHAN Glola ! CH ! AK HI LEGEND Tsdo NARI ! I N O International Boundary I R O U HD NI NK MIK MA Resi ! Setepi ! Kazbegi RUSSIANSOUTH OSSETIA FEDERATION ZAKA Phase VI ! Phase III (Area Adjacent to South Ossetia - AA to SO) TE Pansheti R ! G NK ! I Suatisi U ! Toti ! ! ! Tsotsilta Karatkau ! Achkhoti GaiboteniArsha! ! ! S H! City N O Tkarsheti ST ! Mna U ! Garbani S ! ! K A N A GARUL K Sioni L Abano ! I ! ! Sno ! Pkh!elshe Vardisubani Khurtisi ! ! Village Ketrisi ! ! Kvadja U ! N Kanobi ! K ! Shua Kozi Zemo Okrokana ! ! ! Shua Sba Sevardeni ! ! ! Road Network Kvemo Kozi ! Kvemo Okrokana ! !Kvemo Jomaga Nogkau Zemo Roka ! ! Zemo Jomaga Kvemo Sba ! Shua Roka ! Railway Kvedi ! Artkhmo ! Kobi ! Cheliata ! ! Almasiani Ukhati ! ! Leti ! Non-seasonal river Zgubiri Skhanari Kvemo Roka ! ! Kevselta ! Vezuri ! ! A Kabuzta OR Edisa ! Khodzi J ! ! Tsedisi Tamagini JE ! ! ! Bzita Lakes ! Zaseta Kiro!vi ! Nadarbazevi! Chasavali ! Nakreba ! Kvaisi ! Kobeti Akhsagrina ! ! ! Britata Iri ! Sagilzazi ! ! Sheubani ! ! Kvemo Ermani ! Shua Ermani ! PHASE I Shembuli ! Zemo Bakarta Khadisari ! ! Batra Martgajina Kvemo Bakarta ! ! Duodonastro ! ! Litsi Tlia ! Kasagini ! ! Nogkau ! A Zamtareti S Lesora ! Kvemo Machkhara T ! ! A Tlia P ! Tskere Tsarita Palagkau ! ! ! Keshelta !Gudauri Kola ! Mugure Khugata ! !Bajigata ! ! Chagata Shiboita ! Saritata ! ! Kvemo Koshka Benian-Begoni ! ! Biteta !Tsona Vaneli ! ! Samkhret Chifrani Korogo Iukho !Soncho U Muldarta -

Causes of War Prospects for Peace

Georgian Orthodox Church Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung CAUSES OF WAR PROS P E C TS FOR PEA C E Tbilisi, 2009 1 On December 2-3, 2008 the Holy Synod of the Georgian Orthodox Church and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung held a scientific conference on the theme: Causes of War - Prospects for Peace. The main purpose of the conference was to show the essence of the existing conflicts in Georgia and to prepare objective scientific and information basis. This book is a collection of conference reports and discussion materials that on the request of the editorial board has been presented in article format. Publishers: Metropolitan Ananya Japaridze Katia Christina Plate Bidzina Lebanidze Nato Asatiani Editorial board: Archimandrite Adam (Akhaladze), Tamaz Beradze, Rozeta Gujejiani, Roland Topchishvili, Mariam Lordkipanidze, Lela Margiani, Tariel Putkaradze, Bezhan Khorava Reviewers: Zurab Tvalchrelidze Revaz Sherozia Giorgi Cheishvili Otar Janelidze Editorial board wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Irina Bibileishvili, Merab Gvazava, Nia Gogokhia, Ekaterine Dadiani, Zviad Kvilitaia, Giorgi Cheishvili, Kakhaber Tsulaia. ISBN 2345632456 Printed by CGS ltd 2 Preface by His Holiness and Beatitude Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia ILIA II; Opening Words to the Conference 5 Preface by Katja Christina Plate, Head of the Regional Office for Political Dialogue in the South Caucasus of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung; Opening Words to the Conference 8 Abkhazia: Historical-Political and Ethnic Processes Tamaz Beradze, Konstantine Topuria, Bezhan Khorava - A -

Annex E.4.12 Public

ICC-01/15-4-AnxE.4.12 13-10-2015 1/44 EK PT Annex E.4.12 Public ICC-01/15-4-AnxE.4.12 13-10-2015 2/44 EK PT GEORGIA: A VOIDING WAR IN SOUTH OSSETIA 26 November 2004 international crisis group Europe Report N° I 59 Tbilisi/Brussels GEO-OTP-0008-0615 ICC-01/15-4-AnxE.4.12 13-10-2015 3/44 EK PT TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ANO RECOMMENDATIONS i 1. INTRODUCTION 1 II. UNDERLYING CAUSES OF THE CONFLICT 2 A. H1sTORIC/\1, CAust-:s 2 1. Competing narratives of South Ossetia's past.. 2 2. The 1990- 1 992 conflict and its aftermath 3 3. The peace agreement and peace implementation mechanisms 4 B. HUlvl/\N RlGHTS VIOL.I\ TIONS J\ND POPULATION DISPL./\CE:tviEl\T 5 I. Ossetian and Georgian population settlement and displacement.. 5 2. War-time atrocities 7 c. POLITICAL CA USES or rnt CONfLICI 7 D. GEOPOLITICALC AUSES 8 E. POLITICAL-ECONOlvflCC AUSES Of CONfLICT 9 III. UNFREEZI~G THE CONFLICT 11 A. FOCUSING ON THE POLTTTC'\L ECONO\ifTC CAUSES OF CONFLICT I I 1. Attacking greed 1 I 2. Addressing grievance 12 3. The South Ossetian reaction 12 B. THE START OF VIOLENT CONFLICT 14 C. THE UNEASY TRUCE 15 IV. INTER OR INTRA-STATE CONFLICT? 16 A. Gt-:C)R(tl1\N ALLl-:0/\TIONS ON RUSSJ/\'S ROLi·: ] 6 8. Tm: Vn.w FROM RUSSI/\ 17 C. UNITED STATES INVOLVElviENT 18 D. THE OSCE ·19 E. THE EUROPR/\>J UNTOK I 9 F. -

In Arlington, VA

The Politics of Border Walls in Hungary, Georgia and Israel Gela Merabishvili Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Planning, Governance and Globalization Gerard Toal Giselle Datz Joel Peters Susan Allen 22 September 2020 Arlington, VA Keywords: Borders, Nationalism, Security, Geopolitics, Hungary, Israel, Georgia Copyright 2020 Gela Merabishvili The Politics of Border Walls in Hungary, Georgia and Israel Gela Merabishvili ABSTRACT Politicians justify border walls by arguing that it would protect the nation from outside threats, such as immigration or terrorism. The literature on border walls has identified xenophobic nationalism’s centrality in framing border walls as a security measure. Yet, alternative geographic visions of nationhood in Hungary, Georgia and Israel define the fenced perimeters in these countries as the lines that divide the nation and its territory. These cases illustrate the contradiction between the geography of security, marked by the border wall, and the geography of nationhood, which extends beyond the fenced boundary. These cases allow us to problematize the link between “security” and “nationalism” and their relationship with borders. Therefore, this dissertation is a study of the politics of reconciling distinct geopolitical visions of security and nationhood in the making of border walls. Justification of border walls requires the reframing of the national territory in line with the geography articulated by border security and away from the spatially expanded vision of nationhood. A successful reframing of the nation’s geography is a matter of politicians’ skills to craft a convincing geopolitical storyline in favor of the border wall that would combine security and nationalist arguments (Hungary). -

COST of CONFLICT: UNTOLD STORIES Georgian-Ossetian Conflict in Peoples’ Lives

COST OF CONFLICT: UNTOLD STORIES Georgian-Ossetian Conflict in Peoples’ Lives 2016 Editors: Dina Alborova, Susan Allen, Nino Kalandarishvili Publication Manager: Margarita Tadevosyan Circulation: 100 © George Mason University CONTENTS COMMENTS FROM THE EDITORS Dina Alborova, Susan Allen, Nino Kalandarishvili ................................5 Introduction to Georgian stories Goga Aptsiauri ........................................................................................9 Georgian untold stories ........................................................................11 Intorduction to South Ossetian stories Irina Kelekhsaeva ...................................................................................55 South Ossetian untold stories ...............................................................57 3 COMMENTS FROM THE EDITORS “Actual or potential conflict can be resolved or eased by appealing to common human capabilities to respond to good will and reasonableness”1 The publication you are holding is “Cost of Conflict: Untold Sto- ries-Georgian-Ossetian Conflict in Peoples’ Lives.” This publication fol- lows the collection of analytical articles “Cost of Conflict: Core Dimen- sions of Georgian-South Ossetian Context.” This collection brings together personal stories told by people who were directly affected by the conflict and who continue to pay a price for the conflict today. In multilayered analysis of the conflict and of ways of its resolution the analysis of the human dimension is paid much less attention. This subse- quently -

Up in Flames

Up In Flames Humanitarian Law Violations and Civilian Victims in the Conflict over South Ossetia Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-427-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org January 2009 1-56432-427-3 Up In Flames Humanitarian Law Violations and Civilian Victims in the Conflict over South Ossetia Map of South Ossetia ......................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 2 Overview .......................................................................................................................