Zone Fever, Project Fever: Development Policy, Economic Transition, and Urban Expansion in China*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUZHOU Suzhou Asian City Report Suzhou Asian City Report

– 1H/2020 Asian City Report 25th Floor, Two ICC MARKET No. 288 South Shaanxi Road IN Shanghai MINUTES China Savills Research SUZHOU Suzhou Asian City Report Suzhou Asian City Report Grade A office rents fall as vacancy rates reach multi- COVID-19 had a significant impact on Suzhou’s retail year highs market, both for landlords and tenants SUPPLY AND DEMAND SUPPLY AND DEMAND GRAPH 3: Shopping Mall Supply and Vacancy Rate, 2015 to GRAPH 1: Suzhou Grade A Office Market New Supply, Net Take-up Suzhou’s retail sales contracted by 9.2% YoY in the first six months of 2020 and Vacancy Rate, 2015 to 1H/2020 Suzhou has seen a swift economic recovery following the outbreak of 1H/2020 Supply (LHS) Take-up (LHS) Vacancy (RHS) COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns. Industrial added value from due to the continued fallout from COVID-19, though this figure compares favourably with the 18.4% contraction recorded in the first quarter. Online 600,000 35% above a designated scale in Suzhou increased by 1.6% year-on-year (YoY) Supply (LHS) Vacancy (RHS) in 1H/2020, while the value of monthly output recorded four consecutive retail sales, however, recorded phenomenal growth, expanding 37.6% 1,250,000 15% months of growth. Suzhou’s four leading industries, namely biomedicine, YoY. Under the promotion of policies such as the “night economy” and 500,000 30% new-generation information technology, nanotechnology and artificial consumer coupons, Suzhou’s retail market recovered swiftly in 1H/2020. intelligence contributed 21.6% of total added value. -

Tier 1 Manufacturing Sites

TIER 1 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced January 2021 SUPPLIER NAME MANUFACTURING SITE NAME ADDRESS PRODUCT TYPE No of EMPLOYEES Albania Calzaturificio Maritan Spa George & Alex 4 Street Of Shijak Durres Apparel 100 - 500 Calzificio Eire Srl Italstyle Shpk Kombinati Tekstileve 5000 Berat Apparel 100 - 500 Extreme Sa Extreme Korca Bul 6 Deshmoret L7Nr 1 Korce Apparel 100 - 500 Bangladesh Acs Textiles (Bangladesh) Ltd Acs Textiles & Towel (Bangladesh) Tetlabo Ward 3 Parabo Narayangonj Rupgonj 1460 Home 1000 - PLUS Akh Eco Apparels Ltd Akh Eco Apparels Ltd 495 Balitha Shah Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1800 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Albion Apparel Group Ltd Thianis Apparels Ltd Unit Fs Fb3 Road No2 Cepz Chittagong Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Artistic Design Ltd 232 233 Narasinghpur Savar Dhaka Ashulia Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Hameem - Creative Wash (Laundry) Nishat Nagar Tongi Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Aykroyd & Sons Ltd Taqwa Fabrics Ltd Kewa Boherarchala Gila Beradeed Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bespoke By Ges Unip Lda Panasia Clothing Ltd Aziz Chowdhury Complex 2 Vogra Joydebpur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Asrotex Ltd Betjuri Naun Bazar Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Metro Knitting & Dyeing Mills Ltd (Factory-02) Charabag Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Tanzila Textile Ltd Baroipara Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Taqwa -

Introduction

Joint Center for Housing Studies Harvard University Housing and Economic Development in Suzhou, China: A New Approach to Deal with the Inseparable Issues ZhuXiaoDi,HuangLei,andZhangXinsheng W00-4 July 2000 Zhu Xiao Di is a research analyst at the Joint Center for Housing Studies; Huang Lei is a doctor of design candidate at the Harvard Design School; and Zhang Xinsheng is a visiting research fellow at the Harvard Business School. by Zhu Xiao Di, Huang Lei and Zhang Xinsheng. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including notice, is given to the source. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University or of any of the persons or organizations providing support to the Joint Center for Housing Studies. The authors are grateful to have received grammatical assistance from Bulbul Kaul at the Joint Center for Housing Studies, as none of the authors are native English speakers. Housing and Economic Development in Suzhou, China: A New Approach to Deal with the Inseparable Issues ZhuXiaoDi,HuangLei,andZhangXinsheng Joint Center for Housing Studies W00-4 July 2000 Abstract This is a case study of Suzhou, China, an ancient city of over two thousand years that upgraded itself during the 1990s from a medium-sized city to fifth in China, ranked according to GDP. At the beginning of the decade, the city faced a macroeconomic contraction in the nation, a questionable or unsustainable local economic development model, an enormous task of preserving historical sites, and the pressure of improving the living standards of its residents, which included changing their meager housing conditions. -

Report to Council Agenda Item 6.4

Page 1 of 24 Report to Council Agenda item 6.4 Post travel report by Councillor Kevin Louey and Councillor Philip Le Liu 29 May 2018 – City of Melbourne mission to Osaka, Japan and Beijing, Tianjin, Wuxi and Suzhou China, March 2018 Presenter: David Livingstone, Manager International and Civic Services Purpose and background 1. To report to Council on the travel undertaken by Councillor Kevin Louey as mission leader and Councillor Philip Le Liu to Osaka, Japan and Beijing, Tianjin, Wuxi and Suzhou, China leading the City of Melbourne business mission for the period from 21 to 30 March 2018. 2. On 12 December 2017, the Future Melbourne Committee approved Councillors travel to lead the mission to promote Melbourne’s key capabilities in health and life sciences, sustainable urban development, innovation, start ups and general aviation. Twenty two businesses and organisations were recruited to participate. The planning and delivery of the mission is a major initiative in year 1 of the Council Plan 2017-2021. 3. The comprehensive mission program included pre-departure workshops, tailor-made business match sessions, market opportunity briefings, site visits and networking events. The program built upon Council’s long standing city-to-city partnerships and identified business opportunities aligned with Melbourne sector capabilities that are globally recognised. 4. On-ground program was coordinated utilising Council’s strong partnerships with economic development agencies, key industry groups and bi-lateral Chambers of Commerce in each city, and offshore posts of Australian federal government and Victorian government. 5. The civic delegation held high level meetings with the Mayor Yoshimura, Mayor of Osaka; Vice Mayor of Tianjin, Mayor Mayor of Wuxi and Vice Mayor Xu Meijian, Vice Mayor of Suzhou. -

4 Recent Developments in Ftzs and Port Hinterlands in Asia and Europe

Chapter 4: Recent developments in FTZs and port hinterlands in Asia and Europe 45 4 Recent developments in FTZs and port hinterlands in Asia and Europe 4.1 FTZs in Asia Many countries in Asian region have introduced FTZs to develop their national economies by attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) into the FTZs. In a world of limited amounts of investment funding available most Asian countries have selected this policy partly because it is easier to provide relatively well developed infrastructures in these small special areas than to establish good infrastructures throughout the whole country in a short period of time. The characteristics of FTZs in Asian countries are basically same as described in Chapter 2. FTZs are considered as outside of customs territory, are designed to attract FDI and to provide a business friendly environment with incentives, good infrastructure and other advantages. Most of all, FTZs, whether or not they are referred to by that name, have concentrated traditionally on manufacturing for export, and many of them are located along the coast or near sea transport routes to leverage international transportation. Some differences in Asian FTZs can be attributable to differences in political, economic and social situations. For example, it could be argued that the whole of Singapore is a FTZ, while almost all other countries, such as the Republic of Korea and Malaysia, have designated very specific and small areas as FTZs compared to the size of whole country. The situation in China is different again. Since China opened its economy to the world in 1980s, the country has introduced many kinds of special zones of various sizes covering large to relatively small areas, For example, Xiamen Special Economic Zone covers an area of 1,565 square kilometres and has a population of about 1.31 million while Tianjin Free Trade Zone (Bonded Zone) covers an area of five square kilometres. -

Global Sourcing Map Factory List - Bangladesh

Information last updated July 2018 Global Sourcing Map Factory List - Bangladesh Factory Name Address Country Total Men Women Number of Workers Afiya Knitwear Ltd 10/ 2 Durgapur Ashulia Savar Dhaka 1341 Bangladesh 579 288 (49.7)% 291 (50.3)% AKH Apparels Ltd 128 Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka 1340 Bangladesh 2188 971 (44.4)% 1217 (55.6)% AKH Eco Apparels Ltd 495 Balitha Shah-Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1800 Bangladesh 5418 3000 (55.4)% 2418 (44.6)% Alpha Knitting Wear Limited 888 Shewrapara, 1St & 2Nd Floor Begum Rokeya Shoroni Mirpur Dhaka 1216 Bangladesh 2307 682 (29.6)% 1625 (70.4)% Ananta Denim Technology Ltd Noyabari Kanchpur Sonargaon Narayanganj Bangladesh 4833 2394 (49.5)% 2439 (50.5)% Ananta Huaxiang Ltd 222, 223, H2-H4, Adamjee Epz Shiddirgonj Narayanganj Dhaka Bangladesh 2039 1184 (58.1)% 855 (41.9)% Anowara Knit Composite Ltd Mulaid Mawna Sreepur Gazipur Bangladesh 1979 1088 (55.0)% 891 (45.0)% Apex Lingerie Limited Chandora Kaliakoir Gazipur Bangladesh 3937 2041 (51.8)% 1896 (48.2)% Arunima Sportswear Ltd Dewan Idris Road Zirabo Ashulia Savar Dhaka Bangladesh 4481 2561 (57.2)% 1920 (42.8)% Primark does not own any factories and is selective about the suppliers with whom we work. Every factory which manufactures product for Primark has to commit to meeting internationally recognised standards, before the first order is placed and throughout the time they work with us. The factories featured on Primark’s Global Sourcing Map are Primark’s suppliers’ production sites which represent over 95% of Primark products for sale in Primark stores. A factory is detailed on the Map only after it has produced products for Primark for a year and has become an established supplier. -

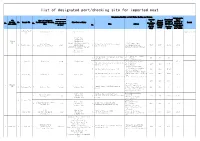

List of Designated Port/Checking Site for Imported Meat

list of designated port/checking site for imported meat Integration Facility of Cold Chain Checking and Storage Comprehensive Port Category Capacity Comprehensi CIQ Name of Designated Area of Import (harbour,river of ve Import directly No. Branch CIQ Port/Designated Checking First Port of Entry Checking Capacity of Remark No. No. port,airport,ro Specialize Capacity of under AQSIQ Site Name Address Platform Designated ad etc.) No. d Cold Integration (square Port/Designat Storage Facility meter) ed Checking (Ton) (10000 Site (10000 Capital airport 1 1 Capital Airport airport Capital Airport 1 Temporary in Use CIQ Tianjin Port Dayaowan Port Beijing 1 Bayuquan Port CIQ Erennhot Designated Port for Cold Storage,Jingjin Beijing Pinggu Beijing Jing-jin Port International 2 Pinggu office 2 road Imported meat 2 Port,Mafang Logistics 9600 1600 16.64 16.64 International Land Port Logistic Co.,Ltd. Qianwan Port, Huangdao Distirct Base,Pinggu District,Beijing Yantai Port Capital Airport Lianyungang Port No.3,Nankang Road,Gangwan China Merchants International Cold Chain 3 Avenue,Nanshan 3000 500 18.3 (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. District,Shenzhen City 3 Shekou CIQ 3 Shekou Port harbour Shekou Port Bonded Port Area,Qianhai 21.65 China Merchants International Cold Chain Bay,No.53,Linhai 4 7000 208.8 3.35 (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. Avenue,Nanshan District,Shenzhen City No.3,Yantian Road,Yantian 5 Shenzhen Baohui Logistics Co.,Ltd 3500 2000 58.64 District,Shenzhen City East Gate of No.439,Donghai 6 Shenzhen Ruiyuan Cold Chain Co.,Ltd Road,Yantian District,Shenzhen 11000 -

Best-Performing Citieschina 2015

SEPTEMBER 2015 Best-Performing Cities CHINA 2015 The Nation’s Most Successful Economies Perry Wong and Michael C.Y. Lin SEPTEMBER 2015 Best-Performing Cities CHINA 2015 The Nation’s Most Successful Economies Perry Wong and Michael C.Y. Lin ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors are grateful to Laura Deal Lacey, managing director of the Milken Institute Asia Center; Belinda Chng, the center’s associate director for innovative finance and program development; and Cecilia Arradaza, the Institute’s executive director of communications, for their support in developing an edition of our Best-Performing Cities series focused on China. We thank Betty Baboujon for her meticulous editorial efforts as well as Ross DeVol, the Institute’s chief research officer, and Minoli Ratnatunga, economist at the Institute, for their constructive comments on our research. ABOUT THE MILKEN INSTITUTE A nonprofit, nonpartisan economic think tank, the Milken Institute works to improve lives around the world by advancing innovative economic and policy solutions that create jobs, widen access to capital, and enhance health. We produce rigorous, independent economic research—and maximize its impact by convening global leaders from the worlds of business, finance, government, and philanthropy. By fostering collaboration between the public and private sectors, we transform great ideas into action. The Milken Institute Asia Center analyzes the demographic trends, trade relationships, and capital flows that will define the region’s future. ©2015 Milken Institute This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................ -

Supplier Name Manufacturing Site Name Address Product

TIER 1 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced July 2021 SUPPLIER NAME MANUFACTURING SITE NAME ADDRESS PRODUCT TYPE No of EMPLOYEES Albania Calzificio Eire Srl Italstyle Shpk Kombinati Tekstileve 5000 Berat Apparel 100 - 500 Bangladesh Aak Ltd Bangladesh Sgwicus (Bd) Limited Plot 73 77 80 Depz Ganakbari Savar Apparel 1000 - PLUS Akh Eco Apparels Ltd Akh Eco Apparels Ltd 495 Balitha Shah Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1800 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Artistic Design Ltd 232 233 Narasinghpur Savar Dhaka Ashulia Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Noman Terry Towel Mills Ltd Vawal Mizapur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Aykroyd & Sons Ltd Alim Knit (Bd) Ltd Nayapara Kashimpur Gazipur 1750 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Aykroyd & Sons Ltd Taqwa Fabrics Ltd Kewa Boherarchala Gila Beradeed Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bespoke By Unip Lda Panasia Clothing Ltd Aziz Chowdhury Complex 2 Vogra Joydebpur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bioworld International Ltd Turag Garments & Hosiery Mills Ltd South Panishail Zirani Bazar Kashimpur Joydebpur Gazipur 1349 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Blues Clothing Ltd Dird Composite Textiles Ltd Shathiabari Dhaladia Rajendrapur Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Blues Clothing Ltd Turag Garments & Hosiery Mills Ltd South Panishail Zirani Bazar Kashimpur Joydebpur Gazipur 1349 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Asrotex Ltd Betjuri Naun Bazar Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Bea-Con Knitwear Ltd (Factory-2) South -

Visionary Partnership Knowledge Innovation

KNOWLEDGE INNOVATION VISIONARY PARTNERSHIP “ China and Singapore are very different. Yet, we share much in common. We aspire to strengthen the three key pillars of building a competitive economy, cohesive society and sustainable environment. The joint development of the VISIONARY Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) has provided a special platform for the leaders on both sides to share and learn from each other. Together, we have created a SIP that is pro-business, pro-worker and pro-environment, all at the same time. PARTNERSHIP This, in essence, is what the Singapore Software is all about.” Mr Lim Swee Say, then-Minister of Manpower, Singapore KNOWLEDGE “ The Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) has evolved to be a successful model for sustainable economic development for cities across the world, epitomising an inclusive, vibrant INNOVATION community. SIP has proven to be capable of surmounting multi-dimensional challenges of urban governance, attaining key UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly the SDGs on Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, and Lessons and Insights Sustainable Cities and Communities.” from the China-Singapore Suzhou Industrial Park from the China-Singapore Lessons and Insights Ms Maimunah Mohd Sharif, UN–Habitat, Executive Director Suzhou Industrial Park Visionary Partnership, Knowledge Innovation: Lessons and Insights from the China-Singapore Suzhou Industrial Park seeks to distil the key lessons and insights from the development experience of the Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) in China. Besides discussing the shared journey undertaken by Singapore and China, the publication delves into areas of experience and guiding principles that would be relevant and applicable to the urbanisation challenges of cities within China and internationally. -

China City Profiles 2012 an Overview of 20 Retail Locations

China City Profiles 2012 An Overview of 20 Retail Locations joneslanglasalle.com.cn China Retail Profiles 2012 The China market presents a compelling opportunity for retailers. China’s retail sector has long been firmly underpinned by solid demand fundamentals–massive population, rapid urbanization and an emerging consumer class. Annual private consumption has tripled in the last decade, and China is on track to become the world’s second largest consumer market by 2015. China’s consumer class will more than double from 198 million people today to 500 million by 2022, if we define it as people earning over USD 5,000 per annum in constant 2005 dollars. It is never too late to enter the China market. China’s economic growth model is undergoing a shift from investment- led growth to consumption-led growth. It is widely recognized that government-led investment, while effective in the short term, is not the solution to long-term growth. With its massive accumulated household savings and low household debt levels, China’s domestic consumption offers immense headroom for growth. China’s leaders are acutely aware of the urgency to effect changes now and are more eager than ever before to tap its consumers for growth. Already, the government has set in motion a comprehensive range of pro-consumption policies to orchestrate a consumption boom. Broadly, the wide-ranging policies include wage increases, tax adjustments, strengthening of the social safety net, job creation, promotion of urbanization and affordable housing. While the traditional long-term demand drivers–urbanization, rising wealth and robust income growth–remain firmly intact, China’s retail story has just been given a structural boost. -

(China) Limited Suzhou New District Sub-Branch

5th Jun 2020 Dear Valued Customer, Ref: Business Optimization of Standard Chartered Bank (China) Limited Suzhou New District Sub-Branch To further optimize the business, Standard Chartered Bank (China) Limited Suzhou New District Sub-Branch is planned to move out of Unit 101&103, Ground Floor, Jinhe International Center, No. 88, Shishan Road, New District, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province in late Jul 2020(specific date is subject to regulatory approval). You’re cordially invited to visit Suzhou Industrial Park Sub-branch for retail banking related services from 20th Jul 2020, or you may contact your relationship manager or service manager in advance for appointment. Standard Chartered Bank (China) Limited Suzhou Suxiu Rd Industrial Park Sub-branch St Xingyang Xinghan St Suzhou Industrial Address: Park Sub-Branch Unit 0103, International Building, No. 2 West Suzhou Avenue, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, 215021, P.R. China Business Hours: Counter Service(Cash service) Monday To Friday 09:00~16:30 Financial Consultancy Service Monday To Friday 09:00~18:00 W Suzhou Ave Telephone: 0512-67630198-66166 With reference to business banking services, you may visit Suzhou main branch from 20th Jul 2020 for services. Your designated relationship manager/designated service manager will contact you for the details as well. Standard Chartered Bank (China) Limited Suzhou Suxiu Rd Xingyang St Xingyang Main Branch Xinghan St Suzhou Address: Main Branch Unit 1001-1007, International Building, No. 2 West Suzhou Avenue, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, 215021, P.R. China Business Hours: Monday To Friday 09:00~18:00 Telephone: 0512-67630198 W Suzhou Ave You can also manage your related banking through our other channels of online banking, mobile banking, phone banking, video banking etc.