Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amcham Shanghai Nanjing Center

An Overview of AmCham Shanghai Nanjing Center Jan 2020 Stella Cai 1 Content ▪ About Nanjing Center ▪ Program & Services ▪ Membership Benefits ▪ Become a Member 2 About Nanjing Center The Nanjing Center was launched as an initiative in March 2016. The goal of the Center is to promote the interests of U.S. Community Connectivity Content business in Nanjing and is managed by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai Yangtze River Delta Network. About Nanjing Center – Member Companies EASTMAN Honeywell Cushman Padel Wakefields Sports PMC Hopkins Nanjing Emerson Center Kimball Electronics KPMG Raffles Medical Herman Kay King & Wood Mallesons ▪ About Nanjing Center ▪ Program & Services ▪ Membership Benefits ▪ Become a Member 5 Programs & Services Government Dialogue & Dinner Government Affairs NEXT Summit US VISA Program Member Briefing US Tax Filing Leadership Forum Recruitment Platform Women’s Forum Customized Trainings Business Mixer Marketing & Sponsorship Topical Event Industry Committee Nanjing signature event 35 Nanjing government reps 6 American Government reps 150 to 200 execs from MNCs 2-hour R/T discussion + 2-hour dinner Monthly program focuses on politic & macro economy trend China & US Government officials, industry expert as speakers 2-hour informative session Topics: US-China trade relations; Tax reform, Financial sector opening & reform; Foreign investment laws; IPR; Tariffs exclusion 30-40 yr. manager Newly promoted s Grow management A platform & leadership 5 30 company employee speakers s AmCham granted Certificate Monthly -

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Effects of an Innovative Training Program for New Graduate Registered Nurses: A

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.11.20192468; this version posted September 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Effects of an Innovative Training Program for New Graduate Registered Nurses: a Comparison Study Fengqin Xu 1*, Yinhe Wang 2*, Liang Ma 1, Jiang Yu 1, Dandan Li 1, Guohui Zhou 1, Yuzi Xu 3, Hailin Zhang 1, Yang Cao 4 1 The First Affiliated Hospital of Kangda College of Nanjing Medical University, the First People’s Hospital of Lianyungang, the Affiliated Lianyungang Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Lianyungang 222000, Jiangsu, China 2 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School, Nanjing, 210008, Jiangsu, China 3 Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, Zhejiang, China 4 Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medical Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro 70182, Sweden * The authors contributed equally to this work. Correspondence authors: Yang Cao, Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medical Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro 70182, Sweden. Email: [email protected] Hailin Zhang, the First Affiliated Hospital of Kangda College of Nanjing Medical University, the First People’s Hospital of Lianyungang, the Affiliated Lianyungang Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Lianyungang 222000, Jiangsu, China. 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

Monster Typhoon on Way Will Inevitably Be Involved in Stoopman Said

4 Friday, July 8, 2016 Precipitation brought by the typhoon will definitely take the lake to a more dangerous level.” Zhang Tao, chief forecaster at the National Meteorological Center, CHINA speaking of Taihu Lake near Shanghai CHINA DAILY » CHINADAILY.COM.CN/NATION DEVELOPMENT STORMS COURTS Tibetan culture, Greek firm told to pay education thriving for Chinese By WANG XIAODONG medical and astrological in Lhasa school — plus around 20 sec salvage work wangxiaodong@chinadai ular private schools and no ly.com.cn public schools, he said. By the end of last year, the By CAO YIN Modernization of the number of various types of [email protected] Tibet autonomous region schools and colleges in Tibet will contribute to the protec exceeded 1,500, and the pri China’s top court ordered a tion of traditional Tibetan maryschool enrollment rate Greek company to pay a Chi culture, experts said at a con reached nearly 99 percent, nese transport authority 6.59 ference on Tibet’s develop according to the regional million yuan ($985,000) on ment in Lhasa on Thursday. government. Thursday for breaching a sal More than 130 scholars, The central government vage agreement, overturning officials and correspondents has made significant efforts the original ruling. from more than 30 countries over the past decades to help Archangelos Investment and regions were in attend preserve and modernize tra E.N.E, the Greek corporation, ance at the 2016 Forum on ditional Tibetan culture, had agreed that the Nanhai the Development of Tibet, including improving educa Rescue Bureau of the Ministry hosted by the State Council tion and research in Tibetol of Transport would salvage its Information Office and the ogy, Zheng said. -

China June 2013.Cdr

VOL. XXV No. 6 June 2013 Rs. 10.00 Chinese President Xi Jinping met with U.S. President Barack Obama at the Annenberg Retreat, California, the United States on June 7, 2013. Chinese Vice President Li Yuanchao, who is also a member of the Chinese Film Festival was held from June 18 to 23, 2013 at Siri Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China Central Fort Auditorium, New Delhi. Mr. Cai Fuchao, Director of Chinese Committee, met with Prakash Karat, General Secretary of State General Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film Communist Party of India (Marxist) in Beijing, China on June 19, and Television, Mr. Manish Tewari, Minister of Information and 2013. Broadcasting, Government of India, Chinese Ambassador Mr. Wei Wei, and Mr. Jackie Chan, legendary Chinese actor attended the inaugural ceremony and screening of film Chinese Zodiac on June 18. Lamp lighting ceremony was held at the Chinese Film Festival on Mr. Jackie Chan sang the song Country at the Inaugural June 18. Ceremony of Chinese Film Festival at Siri Fort Auditorium, New Delhi on June 18. Chinese Ambassador Wei Wei met with Rahul Gandhi, Vice Mr. Zhou Huaiyang, Professor of the School of Marine and Earth President of the Indian National Congress Party at Rahul’s office Science at Tongji University, waved as he came out of the on May 7, 2013. They expressed their willingness to further Jiaolong manned deep-sea submersible after a deep-sea dive into promote cooperation between the two countries. the South China Sea on June 18, 2013. The Jiaolong manned deep-sea submersible carried him as crew member during a deep-sea dive. -

Jiangsu(PDF/288KB)

Mizuho Bank China Business Promotion Division Jiangsu Province Overview Abbreviated Name Su Provincial Capital Nanjing Administrative 13 cities and 45 counties Divisions Secretary of the Luo Zhijun; Provincial Party Li Xueyong Committee; Mayor 2 Size 102,600 km Shandong Annual Mean 16.2°C Jiangsu Temperature Anhui Shanghai Annual Precipitation 861.9 mm Zhejiang Official Government www.jiangsu.gov.cn URL Note: Personnel information as of September 2014 [Economic Scale] Unit 2012 2013 National Share (%) Ranking Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 100 Million RMB 54,058 59,162 2 10.4 Per Capita GDP RMB 68,347 74,607 4 - Value-added Industrial Output (enterprises above a designated 100 Million RMB N.A. N.A. N.A. N.A. size) Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery 100 Million RMB 5,809 6,158 3 6.3 Output Total Investment in Fixed Assets 100 Million RMB 30,854 36,373 2 8.2 Fiscal Revenue 100 Million RMB 5,861 6,568 2 5.1 Fiscal Expenditure 100 Million RMB 7,028 7,798 2 5.6 Total Retail Sales of Consumer 100 Million RMB 18,331 20,797 3 8.7 Goods Foreign Currency Revenue from Million USD 6,300 2,380 10 4.6 Inbound Tourism Export Value Million USD 328,524 328,857 2 14.9 Import Value Million USD 219,438 221,987 4 11.4 Export Surplus Million USD 109,086 106,870 3 16.3 Total Import and Export Value Million USD 547,961 550,844 2 13.2 Foreign Direct Investment No. of contracts 4,156 3,453 N.A. -

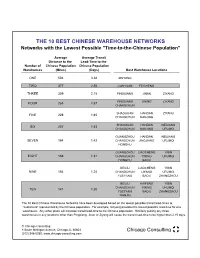

10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-To-The-Chinese Population"

THE 10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-to-the-Chinese Population" Average Average Transit Distance to the Lead-Time to the Number of Chinese Population Chinese Population Warehouses (Miles) (Days) Best Warehouse Locations ONE 504 3.38 XINYANG TWO 377 2.55 LIANYUAN FEICHENG THREE 309 2.15 PINGXIANG JINAN ZIYANG PINGXIANG JINING ZIYANG FOUR 265 1.87 CHANGCHUN SHAOGUAN HANDAN ZIYANG FIVE 228 1.65 CHANGCHUN NANJING SHAOGUAN HANDAN NEIJIANG SIX 207 1.53 CHANGCHUN NANJING URUMQI GUANGZHOU HANDAN NEIJIANG SEVEN 184 1.42 CHANGCHUN JINGJIANG URUMQI HONGHU GUANGZHOU LIAOCHENG YIBIN EIGHT 168 1.31 CHANGCHUN YIXING URUMQI HONGHU BAOJI BEILIU LIAOCHENG YIBIN NINE 154 1.24 CHANGCHUN LIYANG URUMQI YUEYANG BAOJI ZHANGZHOU BEILIU KAIFENG YIBIN CHANGCHUN YIXING URUMQI TEN 141 1.20 YUEYANG BAOJI ZHANGZHOU TIANJIN The 10 Best Chinese Warehouse Networks have been developed based on the lowest possible transit lead-times to "customers" represented by the Chinese population. For example, Xinyang provides the lowest possible lead-time for one warehouse. Any other place will increase transit lead-time to the Chinese population. Similarly putting any three warehouses in any locations other than Pingxiang, Jinan or Ziyang will cause the transit lead-time to be higher than 2.15 days. © Chicago Consulting 8 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60603 Chicago Consulting (312) 346-5080, www.chicago-consulting.com THE 10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-to-the-Chinese Population" Best One City -

The Development of the City with the Historical District: the Comparison with Suzhou and Nantong

The Development of the City with the Historical District: The Comparison with Suzhou and Nantong Shan Lu, Southeast University, China The Asian Conference on Asian Studies 2019 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The current construction of some historical district in China has become a social hot issue. On the one hand, the historical district as a space carrier with a high concentration of regional natural environment, history and culture, urban construction and other elements has high value for protecting the historical heritage of the city and highlighting the urban characteristics. On the other hand, driven by the huge land value and economic value, along with the rapid development of the city, the historical district suffer a considerable degree of constructive damage and is difficult to recover. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of the contradiction between ancient city protection and urban development, and achieving a win-win situation between urban development and historical district protection is a key technical issue in contemporary urban design. This article compares and analyzes the case of Suzhou and Nantong and uses historical mapping and research interview method to analyze the relationship between historical district protection and urban development. First of all, it analyzes the urban development status of the two cities. Secondly, five key issues are identified: urban pattern change, regional function renewal, infrastructure optimization, spatial shape adjustment and lifestyle change. Then analyze its main constraints from three aspects of economy, policy and design. Finally, five strategies are proposed to explore the future development of modern city and historical district protection: Dislocation development, Featured positioning, Regional service, Morphological style and Flexible adjustment. -

Best-Performing Cities: China 2018

Best-Performing Cities CHINA 2018 THE NATION’S MOST SUCCESSFUL ECONOMIES Michael C.Y. Lin and Perry Wong MILKEN INSTITUTE | BEST-PERFORMING CITIES CHINA 2018 | 1 Acknowledgments The authors are grateful to Laura Deal Lacey, executive director of the Milken Institute Asia Center, Belinda Chng, the center’s director for policy and programs, and Ann-Marie Eu, the Institute’s senior associate for communications, for their support in developing this edition of our Best- Performing Cities series focused on China. We thank the communications team for their support in publication as well as Kevin Klowden, the executive director of the Institute’s Center for Regional Economics, Minoli Ratnatunga, director of regional economic research at the Institute, and our colleagues Jessica Jackson and Joe Lee for their constructive comments on our research. About the Milken Institute We are a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank determined to increase global prosperity by advancing collaborative solutions that widen access to capital, create jobs, and improve health. We do this through independent, data-driven research, action-oriented meetings, and meaningful policy initiatives. About the Asia Center The Milken Institute Asia Center promotes the growth of inclusive and sustainable financial markets in Asia by addressing the region’s defining forces, developing collaborative solutions, and identifying strategic opportunities for the deployment of public, private, and philanthropic capital. Our research analyzes the demographic trends, trade relationships, and capital flows that will define the region’s future. About the Center for Regional Economics The Center for Regional Economics promotes prosperity and sustainable growth by increasing understanding of the dynamics that drive job creation and promote industry expansion. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement May 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC .......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 44 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 45 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 52 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 May 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC