The Governance of Megaproject Developments: Lessons from the Comparison of Two Contested Infrastructure Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visite Guidate

Visite Guidate urismo Torino e Turismo Torino e Provincia proposes guided walking tours in the historical town centre Cultural guided tours Provincia propone of Ivrea: the theme is Water, a fundamental visite guidate a piedi T resource for the town’s history. The tours are in nel centro storico di Ivrea: Italian/English and last two hours. tema conduttore l’Acqua, risorsa fondamentale per la storia della città. I tour, in italiano/inglese, durano due ore. Dove e quando | Where and when Mar|Tue 3 giu|June, h 10 & 14 partenza dallo IAT di Ivrea in corso Vercelli 1 | departing from the IAT of Ivrea in corso Vercelli 1 Gio|Thu 5 - ven|Frid 6 giu|June, h 10 Sab|Sat 7 giu|June, h 16 41 partenza dallo Stadio della Canoa | departing from the Stadio della Canoa Itinerario | Itinerary Corso Massimo d’Azeglio - via Palestro - via Cattedrale - piazza Castello - via Quattro Martiri - via Arduino - piazza Vittorio Emanuele - Lungo Dora - Torre di Santo Stefano Stadio della Canoa - corso Nigra - Lungo Dora - Torre di Santo Stefano - via Palestro - via Cattedrale - piazza Castello - via Quattro Martiri - via Arduino - piazza Vittorio Emanuele Per informazioni & prenotazioni | For information & bookings: TIC Ivrea: corso Vercelli 1 – tel. +39-0125618131 – [email protected] Aperto tutti i giorni|open every day h 9-12.30 and 14.30-19 Stand Turismo Torino e Provincia: Stadio della Canoa, 5/8 giu|June, h 10-18 AOSTA MONTE BIANCO GRAN SAN BERNARDO Oropa PPoont-nt- Il nostro territorio. Saint-Martin Carema 2371 2756 A5 Colma di Mombarone Pianprato Sordevolo Campiglia Mte Marzo Quincinetto Pta Tressi Soana BIELLA 2865 Settimo Graglia Our land. -

(Self-)Censorship During Memoranda in Greece, Cyprus, and Spain

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 15–26 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v8i1.2634 Article Constructing Silence: Processes of Journalistic (Self-)Censorship during Memoranda in Greece, Cyprus, and Spain Sofia Iordanidou 1,*, Emmanouil Takas 2, Leonidas Vatikiotis 2 and Pedro García 3 1 Open University of Cyprus, 1045 Nicosia, Cyprus; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Advanced Media Institute, 15234 Athens, Greece; E-Mails: [email protected] (E.M.), [email protected] (L.V.) 3 International University of La Rioja, 28022 Madrid, Spain; E-Mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Submitted: 12 November 2019 | Accepted: 24 December 2019 | Published: 25 February 2020 Abstract What are to be considered as threats against journalism? Whereas the literature on safety of journalists mainly discusses threats as part of armed conflicts, this article studies how other kinds of conflicts such as economic strangulation and the viability threat represent threats against journalists’ work and safety. It argues that acts of intimidation directed against journalists represent an attack on democracy itself as they have the effect of limiting the freedom of expression. The aim of this study is to explore how journalists operate in such a conflict and under such uncertainty, as an implication of (political) pressure caused by the politics of Memoranda in Greece, Cyprus, and Spain. The comparative analysis focuses on possible changes in the processes of message construction and in the journalistic practices of the participants, exploring if, how, and to what extent these changes were imposed to journalists directly or indirectly. Keywords European South; journalists; memorandum; safety; self-censorship; silence Issue This article is part of the issue “Rethinking Safety of Journalists” edited by Kristin Skare Orgeret (Oslo Metropolitan Univer- sity, Norway) and William Tayeebwa (University of Makerere, Uganda). -

The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando

Vincentiana Volume 47 Number 2 Vol. 47, No. 2 Article 5 3-2003 The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando Luigi Chierotti C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Chierotti, Luigi C.M. (2003) "The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando," Vincentiana: Vol. 47 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol47/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando by Luigi Chierotti, C.M. Province of Turin Fr. Durando never wrote a book, nor published one, except for an “educative” pamphlet, written for an Institute of the Daughters of Charity at Fontanetta Po. His collection of letters, however, is a veritable “monument,” and a mine of information on civil and religious life, on the spiritual direction of persons, of the dispositions of governance for the works, etc., from 1831-1880. Today his correspondence is collected in eight large volumes, typewritten, and photocopied, with an accompanying analytical index. I spent a long time working like a Carthusian, in order to transcribe the texts of the “original” letters, the notes, and the reports. -

Analysis of the Wine Sector

ANALYSIS OF THE WINE SECTOR Student: Marta Babrerá Fabregat Tutor: Francesc Xavier Molina Morales DEGREE IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION 2015/2016 1 A. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 4 2. HISTORY OF WINE AS AN ECONOMIC ACTIVITY IN SPAIN ............................. 6 3. TYPES OF GRAPE VARIETES AND WINE MAKING ........................................... 8 3.1. Types of grape varieties ............................................................................... 8 3.1.1. Red varieties .......................................................................................... 8 3.1.2. White varieties ....................................................................................... 9 3.2. Wine Making ................................................................................................ 11 3.2.1. Red wine ............................................................................................... 12 3.2.2. White wine ............................................................................................ 15 4. INDUSTRY CHARACTERISTICS........................................................................ 18 4.1. The wine sector in Spain ............................................................................ 18 4.2. Protected Designations of Origin and Protected Geographical Indications. ............................................................................................................ 18 4.2.1. Protected -

The Alpine Population of Argentera Valley, Sauze Di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: Vestiges of an Occitan Culture and Anthropo-Ecology R

This article was downloaded by: [Renata Freccero] On: 27 April 2015, At: 12:28 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Global Bioethics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: Click for updates http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rgbe20 The Alpine population of Argentera Valley, Sauze di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: vestiges of an Occitan culture and anthropo-ecology R. Frecceroa a Department of Life Sciences and Systems Biology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy Published online: 27 Apr 2015. To cite this article: R. Freccero (2015): The Alpine population of Argentera Valley, Sauze di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: vestiges of an Occitan culture and anthropo-ecology, Global Bioethics, DOI: 10.1080/11287462.2015.1034473 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/11287462.2015.1034473 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

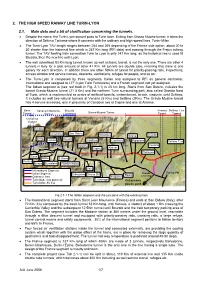

2. the HIGH SPEED RAIWAY LINE TURIN-LYON 2.1. Main Data and a Bit of Clarification Concerning the Tunnels

2. THE HIGH SPEED RAIWAY LINE TURIN-LYON 2.1. Main data and a bit of clarification concerning the tunnels. • Despite the name, the Turin-Lyon doesn’t pass to Turin town. Exiting from Gravio Musine tunnel, it takes the direction of Settimo Torinese where it connects with the ordinary and high-speed lines, Turin–Milan. • The Turin-Lyon TAV length ranges between 254 and 265 depending of the France side option, about 20 to 30 shorter than the historical line which is 287 Km long (RFI data) and passing through the Frejus railway tunnel. The TAV fleeting train connection Turin to Lyon is only 247 Km long, as the historical line is used till Bruzolo, then the new line until Lyon. • The well advertised 53 Km long tunnel, known as well as basic tunnel, is not the only one. There are other 4 tunnels in Italy for a total amount of other 41 Km. All tunnels are double tube, meaning that there is one gallery for each direction. In addition there are other 50Km of tunnel for priority-passing rails, inspections, access window and service tunnels, descents, ventilations, refuges for people, and so on. • The Turin-Lyon is composed by three segments, Italian and assigned to RFI as general contractor, International and assigned to LTF (Lyon Turin Ferroviaire) and a French segment, not yet assigned. The Italian segment is (see red track in Fig. 2.1-1) is 43 km long. Starts from San Didero, includes the tunnel Gravio-Musine tunnel (21.3 Km) and the northern Turin surrounding part, also called Gronda Nord of Turin, which is implemented as series of artificial tunnels, embankment, trench, viaducts, until Settimo. -

Franco's Spain, Queer Nation?

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 33 2000 Franco's Spain, Queer Nation? Gema Pérez-Sánchez University of Miami Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gema Pérez-Sánchez, Franco's Spain, Queer Nation?, 33 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 359 (2000). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol33/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUMMER 2000] Franco' s Spain SPRING 2000] Franco'sSpain 359 FRANCO'S SPAIN, QUEER NATION? Gema Prez-Sdinchez* This Article discusses how, through its juridicalapparatus, the Spanish dictator- ship of FranciscoFranco sought to define and to contain homosexuality, followed by examples of how underground queer activism contested homophobic laws. The Article concludes by analyzing a literary work to illustrate the social impact of Francoism'shomophobic law against homosexuality. INTRODUCTION In the introduction to iEntiendes?: Queer Readings, Hispanic Writ- ings,' Paul Julian Smith and Emilie L. Bergmann regret the lack of historical -

A Glance at Our

AIR QUALITY MONITORING NETWORK AA glanceglance atat ourour airair The air quality monitoring network operating in the province of Turin is managed by Arpa Piemonte. It is composed of 23 monitoring stations (16 background stations and 7 traffic stations) and one mobile station for short measuring Annual report on data collected by campaigns. All the stations are connected to the data acquisition centre provincial air quality monitoring network by telephone lines and transmit hourly measurement result. provincial air quality monitoring network This setup allows a continuous monitoring of the main factors that may affect air quality. Location of measurement stations on the territory is a key factor to achieve a cost-effective air quality monitoring. In Sergio Dall’Olio, above sky 2014 Torino some cases the selected sites must be representative of a large portion of territory, in other cases stations must 20142014 previewpreview represent specific pollution situation like traffic hot spot or single source emissions. A strategic location of measurement points gives extremely representative information on air quality. MEASUREMENT STATIONS AIR QUALITY IN THE PROVINCE OF TURIN Station Address Pollutants Type of station Data collected during the last 10 years by air quality monitoring network Pollutant Situation Baldissero (GDF) (1) Str. Pino Torinese, 1 – Baldissero NO , O , CO, PM10ß, PAHs deposimeter Rural background operating in the province of Turin and managed by Arpa Piemonte show an x 3 sulphur dioxide Beinasco Via S. Pellico, 5 – Beinasco NO x Urban background overall and significant improvement but at the same time confirm the critical NO PM10 , PM10 ß , PM2,5 ß, BTX, PCDD/DF sampling situation of the territory, in particular of the Turin urban area. -

Verso Una Città Metropolitana Del Cibo

Urban&Rural Cooperation: the Metropolitan City of Torino’s projects The Metropolitan Food Agenda The front office for new mountain and rural inhabitants («Living and Working in mountain areas») Working Group Metropolitan Areas Meeting – Eurocities – 18th of june 2021 For Torino Food policy is a new dimension “Food security (is ) a situation that exists when all people, at all times, have phisical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healty life” (Amartya Sen, Nobel on Economy) To feed “Resilient” Cities/Metropolis From agricultural, environmental, market, urban planning, health policies to Food policies From Government to Governance (focus of dynamic relationships between actors: producers, consumers, trade, civil society/stakeholders/lobbies, public authorities) Why we are dealing with Food Policies? Because Food is a primary need of human being (the third one after air and water) essential for Life Because the “access” to food is not only a question of quantity but of quality, not solved even in “rich and developped” countries (obesity/overweigth, diabetes, 50% of diseases linked to the food diet and style, increasing poor people) Because it is an hidden cost for the Public Health budgets Because Public Authorities have a Moral Responsibility to their citizens’ LIFE Because, last but not least, IT IS A QUESTION OF FOOD DEMOCRACY and food justice, THEN A QUESTION OF DEMOCRACY How we reached the Food approach: wich food policy -

The Impractical Supremacy of Local Identity on the Worthless Soils of Mappano Paolo Pileri1 and Riccardo Scalenghe2*

Pileri and Scalenghe City Territ Archit (2016) 3:5 DOI 10.1186/s40410-016-0035-z CASE STUDY Open Access The impractical supremacy of local identity on the worthless soils of Mappano Paolo Pileri1 and Riccardo Scalenghe2* Abstract Introduction: Soil is under pressure worldwide. In Italy, in the last two decades, land consumption has reached an average rate of 8 m2, demonstrating the failure of urban planning in controlling these phenomena. Despite the renewed recognition of the central role of soil resources, which has triggered numerous initiatives and actions, soil resources are still seen as a second-tier priority. No governance body exists to coordinate initiatives to ensure that soils are appropriately represented in decision-making processes. Global Soil Partnership draws our attention to the need for coordination to avoid fragmentation of efforts and wastage of resources. Both at a global and at a local level, the area of fertile soils is limited and is increasingly under pressure by competing land uses for settlement, infrastructure, raw materials extraction, agriculture, and forestry. Discussion and Evaluation: Here, we show that an administrative event, such as the creation of a new small municipality, can take place without any consideration of land and soil risks. This is particularly problematic in the Italian context as recent studies demonstrate that increasing local power in land use decisions coupled with weak control by the central administration and the high fragmentation and small dimension of municipalities has boosted land consumption. The fragmentation of municipalities has been detrimental to land conservation. Case description: The case study of Mappano (in the northwestern Italian region of Piedmont on the periphery of the regional capital city of Turin) is emblematic to demonstrate the role played by the supremacy of local identity or local interests despite the acknowledged importance of the key role played by soil everywhere. -

Piedmont Region Case Study

ReSSI – Regional strategies for sustainable and inclusive territorial development – Regional interplay and EU dialogue Targeted Analysis Annex 5 – Piedmont Region Case Study Version 30/11/2017 This targeted analysis activity is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Giancarlo Cotella, Elena Pede and Marco Santangelo, Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning – Politecnico di Torino (Italy) Advisory Group ESPON EGTC: Michaela Gensheimer (Senior Project Expert, Cluster Coordinator for Project Development and Coordination), Piera Petruzzi (Senior Project Expert, Communication and Capitalisation), Johannes Kiersch (Financial Expert) Information on ESPON and its projects can be found on www.espon.eu. The web site provides the possibility to download and examine the most recent documents produced by finalised and ongoing ESPON projects. This delivery exists only in an electronic version. © ESPON, 2017 Printing, reproduction or quotation is authorised provided the source is acknowledged and a copy is forwarded to the ESPON EGTC in Luxembourg. Contact: [email protected] ISBN: 978-99959-55-16-8 a ReSSI Regional strategies for sustainable and inclusive territorial development – Regional interplay and EU dialogue Table of contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. -

3 3 13 Regional Strategy PP5 Rev2

Regional Strategies Development Including Regional Church Route Description “This project is implemented through the CENTRAL EUROPE Programme co-financed by the ERDF” 1 1 Introduction..................................................................................................................................3 2 A brief description of nature and history.....................................................................................4 3 Socio-economic context and entrepreneurship swot analysis......................................................6 4 Routes And Location Swot Analysis ...........................................................................................7 4.1 VIA FRANCIGENA............................................................................................................7 4.2 Itineraries of taste in the Susa Valley...................................................................................8 5 Heritage And Preservation Swot Analysis...................................................................................9 5.1 The Natural Park Of Alpi Cozie ..........................................................................................9 5.2 Archaeology.......................................................................................................................10 5.3 Abbey and Monasteries......................................................................................................10 5.4 Fresco Cycle.......................................................................................................................10