The Impractical Supremacy of Local Identity on the Worthless Soils of Mappano Paolo Pileri1 and Riccardo Scalenghe2*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

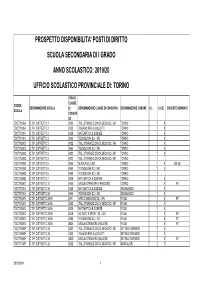

Disp Diritto

PROSPETTO DISPONIBILITA' POSTI DI DIRITTO SCUOLA SECONDARIA DI I GRADO ANNO SCOLASTICO: 2019/20 UFFICIO SCOLASTICO PROVINCIALE DI: TORINO CODICE CLASSE CODICE DENOMINAZIONE SCUOLA DI DENOMINAZIONE CLASSE DI CONCORSO DENOMINAZIONE COMUNE C.I. C.O.E. DOCENTE NOMINATO SCUOLA CONCOR SO TOCT701004 C.T.P. DISTRETTO 2 A022 ITAL.,STORIA,ED.CIVICA,GEOG.SC.I GR TORINO 1 0 TOCT701004 C.T.P. DISTRETTO 2 A023 ITALIANO PER ALLOGLOTTI TORINO 1 0 TOCT701004 C.T.P. DISTRETTO 2 A028 MATEMATICA E SCIENZE TORINO 1 0 TOCT701004 C.T.P. DISTRETTO 2 A060 TECNOLOGIA SC. I GR. TORINO 1 0 TOCT70200X C.T.P. DISTRETTO 3 A022 ITAL.,STORIA,ED.CIVICA,GEOG.SC.I GR TORINO 1 0 TOCT70200X C.T.P. DISTRETTO 3 A060 TECNOLOGIA SC. I GR. TORINO 1 0 TOCT70300Q C.T.P. DISTRETTO 5 A022 ITAL.,STORIA,ED.CIVICA,GEOG.SC.I GR TORINO 1 0 TOCT70300Q C.T.P. DISTRETTO 5 A022 ITAL.,STORIA,ED.CIVICA,GEOG.SC.I GR TORINO 1 TOCT70400G C.T.P. DISTRETTO 6 A030 MUSICA SC. I GR. TORINO 1 0 DM 631 TOCT70400G C.T.P. DISTRETTO 6 A060 TECNOLOGIA SC. I GR. TORINO 1 0 TOCT70400G C.T.P. DISTRETTO 6 A060 TECNOLOGIA SC. I GR. TORINO 1 TOCT70500B C.T.P. DISTRETTO 7 A028 MATEMATICA E SCIENZE TORINO 1 0 TOCT706007 C.T.P. DISTRETTO 10 AA25 LINGUA STRANIERA (FRANCESE) TORINO 1 0 FIT TOCT707003 C.T.P. DISTRETTO 24 A028 MATEMATICA E SCIENZE GRUGLIASCO 1 0 TOCT707003 C.T.P. DISTRETTO 24 A060 TECNOLOGIA SC. I GR. -

Visite Guidate

Visite Guidate urismo Torino e Turismo Torino e Provincia proposes guided walking tours in the historical town centre Cultural guided tours Provincia propone of Ivrea: the theme is Water, a fundamental visite guidate a piedi T resource for the town’s history. The tours are in nel centro storico di Ivrea: Italian/English and last two hours. tema conduttore l’Acqua, risorsa fondamentale per la storia della città. I tour, in italiano/inglese, durano due ore. Dove e quando | Where and when Mar|Tue 3 giu|June, h 10 & 14 partenza dallo IAT di Ivrea in corso Vercelli 1 | departing from the IAT of Ivrea in corso Vercelli 1 Gio|Thu 5 - ven|Frid 6 giu|June, h 10 Sab|Sat 7 giu|June, h 16 41 partenza dallo Stadio della Canoa | departing from the Stadio della Canoa Itinerario | Itinerary Corso Massimo d’Azeglio - via Palestro - via Cattedrale - piazza Castello - via Quattro Martiri - via Arduino - piazza Vittorio Emanuele - Lungo Dora - Torre di Santo Stefano Stadio della Canoa - corso Nigra - Lungo Dora - Torre di Santo Stefano - via Palestro - via Cattedrale - piazza Castello - via Quattro Martiri - via Arduino - piazza Vittorio Emanuele Per informazioni & prenotazioni | For information & bookings: TIC Ivrea: corso Vercelli 1 – tel. +39-0125618131 – [email protected] Aperto tutti i giorni|open every day h 9-12.30 and 14.30-19 Stand Turismo Torino e Provincia: Stadio della Canoa, 5/8 giu|June, h 10-18 AOSTA MONTE BIANCO GRAN SAN BERNARDO Oropa PPoont-nt- Il nostro territorio. Saint-Martin Carema 2371 2756 A5 Colma di Mombarone Pianprato Sordevolo Campiglia Mte Marzo Quincinetto Pta Tressi Soana BIELLA 2865 Settimo Graglia Our land. -

INDICATORS for WASTE PREVENTION and MANAGEMENT Measuring Circularity

INDICATORS FOR WASTE PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT Measuring circularity 4/3/2019 Version 1.0 WP 2 Dissemination level Public Deliverable lead University of Coimbra Authors Joana Bastos, Rita Garcia and Fausto Freire (UC) Reviewers Luís Dias (UC), Leonardo Rosado (Chalmers) This report presents a set of indicators on circular economy, waste prevention and management, and guidance on their application. The indicators provide means to assess the performance of an urban area (e.g., municipality) and monitor progress over time; to measure the effectiveness of strategic planning (e.g., providing insight on the efficiency of implemented strategies and policies); to support decision-making (e.g., on priorities Abstract and targets for developing strategies and policies); and to compare to other urban areas (e.g., benchmark). The work was developed within Task T2.3 of the UrbanWINS project “Definition of a set of key indicators for urban metabolism based on MFA and LCA”, and will be reported in Deliverable D2.3 “Urban Metabolism case studies. Reports for each of the 8 cities that will be subject to detailed study with quantification and analysis of their Urban Metabolism”. Circular economy; Waste prevention and management; Keywords Indicators Contents 1. Introduction ______________________________________________________________ 3 2. Review and selection of indicators ___________________________________________ 4 3. The indicator set __________________________________________________________ 5 3.1. Indicators application matrix ____________________________________________ 7 4. Indicators description and application ________________________________________ 8 4.1. Waste indicators ______________________________________________________ 8 4.2. Circular economy indicators ____________________________________________ 27 5. A cross-city comparative analysis ___________________________________________ 38 5.1. Dashboard indicators results ____________________________________________ 38 5.2. Interpretation and remarks _____________________________________________ 41 6. -

The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando

Vincentiana Volume 47 Number 2 Vol. 47, No. 2 Article 5 3-2003 The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando Luigi Chierotti C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Chierotti, Luigi C.M. (2003) "The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando," Vincentiana: Vol. 47 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol47/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unedited Collection of Letters of Blessed Marcantonio Durando by Luigi Chierotti, C.M. Province of Turin Fr. Durando never wrote a book, nor published one, except for an “educative” pamphlet, written for an Institute of the Daughters of Charity at Fontanetta Po. His collection of letters, however, is a veritable “monument,” and a mine of information on civil and religious life, on the spiritual direction of persons, of the dispositions of governance for the works, etc., from 1831-1880. Today his correspondence is collected in eight large volumes, typewritten, and photocopied, with an accompanying analytical index. I spent a long time working like a Carthusian, in order to transcribe the texts of the “original” letters, the notes, and the reports. -

Deliberazione Della Giunta Regionale 25 Maggio 2018, N. 26-6913

REGIONE PIEMONTE BU24 14/06/2018 Deliberazione della Giunta Regionale 25 maggio 2018, n. 26-6913 Definizione degli ambiti territoriali di scelta dell' ASL TO4 per la Medicina generale e per la Pediatria di libera Scelta entro i quali l'assistito puo' esercitare il proprio diritto di scelta/revoca, rispettivamente, del Medico di Medicina generale e del Pediatra di libera Scelta. A relazione dell'Assessore Saitta: Visto l’art. 19, comma 2, della Legge n. 833/78 che prevede la possibilità di libera scelta del medico, da parte dell’assistibile, nei limiti oggettivi dell’organizzazione sanitaria; visto l’art. 33, comma 3, dell’Accordo Collettivo Nazionale per la disciplina dei rapporti con i Medici di Medicina generale del 23 marzo 2005 e s.m.i. (nel prosieguo ACN MMG) che conferisce alle Regioni la competenza ad articolare il livello organizzativo dell’assistenza primaria in ambiti territoriali di comuni, gruppi di comuni o distretti; visto l’art. 32, comma 3, dell’Accordo Collettivo Nazionale per la disciplina dei rapporti con i Medici Pediatri di libera Scelta del 15 dicembre 2005 e s.m.i. (nel prosieguo ACN PLS) che conferisce alle Regioni la competenza ad articolare il livello organizzativo dell’assistenza primaria pediatrica in ambiti territoriali di comuni, gruppi di comuni o distretti; dato atto che attualmente l’ASL TO4 è articolata in 5 Distretti qui di seguito elencati: • Distretto di Cirie’ e Lanzo Torinese; • Distretto di Chivasso e San Mauro Torinese; • Distretto di Settimo Torinese; • Distretto di Ivrea; • Distretto di Courgnè dato atto che i sei attuali ambiti territoriali per l’assistenza primaria, afferenti il Distretto di Cirie’- Lanzo Torinese, ricomprendono i Comuni qui di seguito elencati: • Lanzo Torinese, Ala di Stura, Balangero, Balme, Cafasse, Cantoira, Ceres, Chialamberto, Coassolo Torinese, Corio, Germagnano, Groscavallo, Lemie, Mezzenile, Monastero di Lanzo, Pessinetto, Traves, Usseglio, Vallo Torinese, Varisella, Viù. -

GUADAGNOLO Il Borgo Di Guadagnolo È Una Frazione Del Comune Di Capranica Prenestina

INFORMAZIONI SU GUADAGNOLO Il borgo di Guadagnolo è una frazione del Comune di Capranica Prenestina. È il centro abitato più alto della Provincia di Roma ed è posto al limite occidentale dei monti Prenestini cHe si trovano quasi al centro del Lazio, a circa 20 cHilometri a Est di Roma. Da qui si gode una vista sublime sulle valli dell’Aniene e del Sacco, verso i monti Simbruini, Ernici e Lepini. La montagna è caratterizzata da varietà botaniche così uniche da essere inserite nella carta regionale del Lazio fra gli ecosistemi da salvaguardare. La sua storia è strettamente collegata con il Santuario della Mentorella, situato su una rupe a picco sulla valle del Giovenzano, che risale al IV sec. d.C., che è ritenuto il più antico Santuario mariano d'Italia e forse d'Europa, meta abituale di fedeli che salgono a deporre le loro preghiere ai piedi della Vergine, oltre che a S. EustacHio (un martire locale) e San Benedetto. Il villaggio si dice nato all'epoca delle incursioni barbaricHe, quando i romani, fuggiascHi, si sarebbero stanziati nei pressi di un antichissimo fortilizio, del quale restano solo i ruderi di una torre precedente il V secolo. Secondo altri il nucleo originario sarebbe stato costruito dai contadini che lavoravano le terre di appartenenza dei Monaci del Santuario, come avvenne negli antichissimi Monasteri di Cassino, di Subiaco e vari altri luoghi. Secondo lo studioso Padre Atanasio Kircher, un insigne monaco del XVII sec., il nome Guadagnolo deriverebbe dai piccoli guadagni cHe locandieri e osti ricavavano dai pellegrini cHe si recavano a visitare il Santuario. -

Pagina 1 Comune Sede Torino Sede Grugliasco Sede Orbassano Torino

Sede Sede Sede Comune Torino Grugliasco Orbassano Torino 21388 794 461 Moncalieri 987 51 29 Collegno 958 70 41 Numero di iscritti alle Rivoli 894 79 72 sedi UNITO di Torino, Settimo Torinese 832 22 10 Grugliasco e Nichelino 752 26 27 Orbassano distinte Chieri 713 55 14 Grugliasco 683 94 32 Venaria Reale 683 26 23 Ad es. sono 958 i Pinerolo 600 19 37 domiciliati a Collegno Chivasso 445 22 3 che sono iscritti a CdS San Mauro Torinese 432 21 7 Orbassano 404 27 31 sono 70 i domiciliati a Carmagnola 393 24 5 Collegno che sono Ivrea 381 23 1 iscritti a CdS con sede Cirié 346 14 12 Caselle Torinese 323 17 12 sono 41 i domiciliati a Rivalta di Torino 307 28 29 Collegno che sono Piossasco 292 16 25 iscritti a CdS con sede Beinasco 284 16 23 Alpignano 274 24 11 Volpiano 271 12 1 Pianezza 264 18 3 Vinovo 262 11 14 Borgaro Torinese 243 16 1 Giaveno 238 12 11 Rivarolo Canavese 232 7 Leini 225 10 4 Trofarello 224 18 5 Pino Torinese 212 8 3 Avigliana 189 14 16 Bruino 173 6 16 Gassino Torinese 173 10 1 Santena 161 13 4 Druento 159 8 6 Poirino 151 12 5 San Maurizio Canavese 151 8 7 Castiglione Torinese 149 8 2 Volvera 135 5 7 None 133 7 3 Carignano 130 4 1 Almese 124 10 4 Brandizzo 120 4 1 Baldissero Torinese 119 5 1 Nole 118 5 3 Castellamonte 116 5 Cumiana 114 6 9 La Loggia 114 7 3 Cuorgné 111 5 2 Cambiano 108 9 5 Candiolo 108 7 2 Pecetto Torinese 108 6 2 Buttigliera Alta 102 9 4 Luserna San Giovanni 101 7 8 Caluso 100 1 Pagina 1 Sede Sede Sede Comune Torino Grugliasco Orbassano Bussoleno 97 6 1 Rosta 90 12 4 San Benigno Canavese 88 2 Lanzo Torinese -

Health Impact of Pm10 and Ozone in 13 Italian Cities

The WHO Regional Office for Europe The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations created in 1948 with the primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. The WHO Regional Office for Europe is one of six regional offices throughout the world, each with its own Over the last few decades, the evidence on the adverse programme geared to the particular health conditions of the countries it serves. effects on health of air pollution has been mounting. A broad range of adverse health outcomes due to short- Member States and long-term exposure to air pollutants, at levels Albania Andorra usually experienced by urban populations throughout Armenia the world, are established. Austria H Azerbaijan EALTH HEALTH IMPACT OF Belarus This report estimates the health impact of PM10 and Belgium Bosnia and Herzegovina ozone on urban populations of 13 large Italian cities. To Bulgaria do so, concentration–response risk coefficients were I Croatia MPACT PM10 AND OZONE Cyprus derived from epidemiological studies, and 25 adverse Czech Republic health outcomes and different exposure scenarios were Denmark Estonia considered. Average PM levels for the years 10 OF IN 13 ITALIAN CITIES Finland 2002–2004 ranged from 26.3 µg/m3 to 61.1 µg/m3. The France PM Georgia health impact of air pollution in Italian cities is large: Germany Greece 8220 deaths a year, on average, are attributable to PM10 10 Hungary 3 concentrations above 20 µg/m . This is 9% of the Iceland AND Ireland mortality for all causes (excluding accidents) in the Israel population over 30 years of age; the impact on short O Italy 3 Kazakhstan term mortality, again for PM10 above 20 µg/m , is 1372 ZONE Kyrgyzstan deaths, which is 1.5% of the total mortality in the whole Latvia Lithuania population. -

Comune Di Caselle Torinese Bando Di Concorso

COMUNE DI CASELLE TORINESE BANDO DI CONCORSO GENERALE PER LA FORMAZIONE DELLA GRADUATORIA PER L’ASSEGNAZIONE IN LOCAZIONE DEGLI ALLOGGI DI EDILIZIA SOCIALE DI RISULTA. (L.R. n. 3/2010 e s.m.i.) E’ indetto, ai sensi dell’articolo 5 della legge regionale 17 febbraio 2010, n. 3, e s.m.i., un bando di concorso per la formazione della graduatoria generale per l’assegnazione degli alloggi di edilizia sociale che si renderanno disponibili nel periodo di vigenza della medesima. Requisiti per partecipare al bando (da possedere alla data del 08/06/2021) Possono presentare domanda di partecipazione al presente bando coloro che siano cittadini italiani o di uno Stato aderente all’Unione europea o cittadini di uno Stato non aderente all’Unione europea, regolarmente soggiornanti in Italia in base alle vigenti normative in materia di immigrazione, o siano titolari di protezione internazionale di cui all’articolo 2 del decreto legislativo 19 novembre 2007, n. 251 (Attuazione della direttiva 2004/83/CE recante norme minime sull’attribuzione, a cittadini di Paesi terzi o apolidi, della qualifica del rifugiato o di persona altrimenti bisognosa di protezione internazionale, nonché norme minime sul contenuto della protezione riconosciuta) e che abbiano la residenza anagrafica o l’attività lavorativa esclusiva o principale da almeno cinque anni nel territorio regionale, con almeno tre anni, anche non continuativi nei Comuni di Ala di Stura, Balangero, Balme, Barbania, Borgaro Torinese, Cafasse, Cantoria, Caselle Torinese, Ceres, Chialamberto, Ciriè, Coassolo Torinese, Corio, Fiano, Front, Germagnano, Groscavallo, Grosso, Lanzo Torinese, Lemie, Levone, Mappano, Mathi, Mezzenile, Monastero di Lanzo, Nole, Pessinetto, Robassomero, Rocca Canavese, San Carlo Canavese, San Francesco al Campo, San Maurizio Canavese, Traves, Usseglio, Vallo Torinese, Varisella, Vauda Canavese, Villanova Canavese, Viù o essere iscritti all’AIRE dei Comuni sopracitati. -

03-Mar-19 Primarie PD 2019

Primarie PD 2019 03-mar-19 COLLEGIO SEGGIO SPECIFICA SEDE INDIRIZZO COMUNI che votano nel seggio Collegio 11 21 SEGGI BANCHETTE, FIORANO CANAVESE, LESSOLO, SALERANO CANAVESE, 11 BANCHETTE SCUOLA MEDIA VIA TORRETTA SAMONE, Loranzé, Colleretto Giacosa, Parella, Quagliuzzo, Strambinello 11 CASTELLAMONTE SEDE PD LARGO TALENTINO 4 AGLIE', BALDISSERO CANAVESE, CASTELLAMONTE, TORRE CANAVESE ALA DI STURA, BALANGERO, BALME, CANTOIRA, CERES, SALA PIANO TERRA, PIAZZA DEL MUNICIPIO CHIALAMBERTO, COASSOLO TORINESE, GERMAGNANO, 11 CERES MUNICIPIO 12 GROSCAVALLO, LANZO TORINESE, LEMIE, MEZZENILE, MONASTERO DI LANZO, PESSINETTO, TRAVES, USSEGLIO, VIU' 11 CIRIE' SEDE PD CORSO MATTEOTTI 16 CIRIE', FIANO, ROBASSOMERO, SAN CARLO CANAVESE COLLERETTO BORGIALLO, CASTELNUOVO NIGRA, COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO, 11 SALA COMUNALE PIAZZA MUNICIPIO CASTELNUOVO CHIESANUOVA, CINTANO ALBIANO D'IVREA, AZEGLIO, BOLLENGO, BORGOMASINO, BUROLO, CARAVINO, COSSANO CANAVESE, MAGLIONE, MERCENASCO, 11 COSSANO SALA MUNICIPALE VIA ROMA PALAZZO CANAVESE, PEROSA CANAVESE, PIVERONE, ROMANO CANAVESE, SAN MARTINO CANAVESE, SCARMAGNO, SETTIMO ROTTARO, STRAMBINO, VESTIGNE', VIALFRE' CANISCHIO, CUORGNE', PRASCORSANO, SAN COLOMBANO 11 CUORGNE' SEDE PD VIA GARIBALDI 27 BELMONTE, FRASSINETTO, INGRIA, PONT-CANAVESE, RONCO CANAVESE, VALPRATO SOANA 11 FORNO CANAVESE SALA COMUNALE VIA VITTORIO VENETO 1 FORNO CANAVESE, RIVARA 11 IVREA LOCALE VIA CASCINETTE 2 IVREA, CASCINETTE D'IVREA ALPETTE, CERESOLE REALE, LOCANA, NOASCA, RIBORDONE, 11 LOCANA SALA CONSILIARE MUNICIPIO SPARONE 11 MATHI SEDE PD VIA -

Orari E Mappe Della Linea Bus 3165

Orari e mappe della linea bus 3165 3165 Ciriè Stazione Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea bus 3165 (Ciriè Stazione) ha 7 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Ciriè Stazione: 20:14 (2) Ciriè Stazione: 07:00 - 20:35 (3) Germagnano: 05:30 - 23:05 (4) Torino Porta Susa: 04:15 - 10:10 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea bus 3165 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea bus 3165 Direzione: Ciriè Stazione Orari della linea bus 3165 8 fermate Orari di partenza verso Ciriè Stazione: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 20:14 martedì 20:14 Germagnano (Stazione Ferroviaria) 38 Via Celso Miglietti, Germagnano mercoledì 20:14 Lanzo (Movicentro) giovedì 20:14 Balangero (Semaforo Stazione) venerdì 20:14 34 Stradale Lanzo, Balangero sabato Non in servizio Mathi (Semaforo Cimitero) domenica Non in servizio 17 Via Piave, Mathi Grosso (Semaforo Villanova) 2 Via Lanzo, Villanova Canavese Informazioni sulla linea bus 3165 Nole (Semaforo Vauda) Direzione: Ciriè Stazione 1 Via Rocca, Nole Fermate: 8 Durata del tragitto: 21 min Cirie' (Ospedale) La linea in sintesi: Germagnano (Stazione 34 Via Battitore, Ciriè Ferroviaria), Lanzo (Movicentro), Balangero (Semaforo Stazione), Mathi (Semaforo Cimitero), Cirie' (Stazione) Grosso (Semaforo Villanova), Nole (Semaforo 3 Piazza Stazione, Ciriè Vauda), Cirie' (Ospedale), Cirie' (Stazione) Direzione: Ciriè Stazione Orari della linea bus 3165 25 fermate Orari di partenza verso Ciriè Stazione: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 07:00 - 20:35 martedì 07:00 - 20:35 Torino (Autostazione Bolzano St. 7) Corso Bolzano, Torino mercoledì 07:00 - 20:35 Baldissera Nord giovedì 07:00 - 20:35 1/B Via Errico Giachino, Torino venerdì 07:00 - 20:35 Largo Massaia sabato 07:00 4 Via Casteldelƒno, Torino domenica Non in servizio Stradella 252 Corso Grosseto, Torino Stampini Via Ettore Stampini, Torino Informazioni sulla linea bus 3165 Direzione: Ciriè Stazione Del Francese Ovest Fermate: 25 434/K Strada Lanzo, Torino Durata del tragitto: 46 min La linea in sintesi: Torino (Autostazione Bolzano St. -

The Alpine Population of Argentera Valley, Sauze Di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: Vestiges of an Occitan Culture and Anthropo-Ecology R

This article was downloaded by: [Renata Freccero] On: 27 April 2015, At: 12:28 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Global Bioethics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: Click for updates http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rgbe20 The Alpine population of Argentera Valley, Sauze di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: vestiges of an Occitan culture and anthropo-ecology R. Frecceroa a Department of Life Sciences and Systems Biology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy Published online: 27 Apr 2015. To cite this article: R. Freccero (2015): The Alpine population of Argentera Valley, Sauze di Cesana, Province of Turin, Italy: vestiges of an Occitan culture and anthropo-ecology, Global Bioethics, DOI: 10.1080/11287462.2015.1034473 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/11287462.2015.1034473 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.