ORR CEPA Rail Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia

Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Contents Foreword 3 Looking Ahead 5 Priorities in Detail • Great Eastern Main Line 6 • West Anglia Main Line 6 • Great Northern Route 7 • Essex Thameside 8 • Branch Lines 8 • Freight 9 A five county alliance • Norfolk 10 • Suffolk 11 • Essex 11 • Cambridgeshire 12 • Hertfordshire 13 • Connecting East Anglia 14 Our counties connected 15 Foreword Our vision is to release the industry, entrepreneurship and talent investment in rail connectivity and the introduction of the Essex of our region through a modern, customer-focused and efficient Thameside service has transformed ‘the misery line’ into the most railway system. reliable in the country, where passenger numbers have increased by 26% between 2005 and 2011. With focussed infrastructure We have the skills and enterprise to be an Eastern Economic and rolling stock investment to develop a high-quality service, Powerhouse. Our growing economy is built on the successes of East Anglia can deliver so much more. innovative and dynamic businesses, education institutions that are world-leading and internationally connected airports and We want to create a rail network that sets the standard for container ports. what others can achieve elsewhere. We want to attract new businesses, draw in millions of visitors and make the case for The railways are integral to our region’s economy - carrying more investment. To do this we need a modern, customer- almost 160 million passengers during 2012-2013, an increase focused and efficient railway system. This prospectus sets out of 4% on the previous year. -

Firstgroup Vies with Virgin in West Coast Rail Bidding War | Business | Guardian.Co.Uk Page 1 of 2

FirstGroup vies with Virgin in west coast rail bidding war | Business | guardian.co.uk Page 1 of 2 Printing sponsored by: FirstGroup vies with Virgin in west coast rail bidding war Aberdeen-based group is frontrunner, along with incumbent, in battle to secure 14-year franchise contract Dan Milmo, industrial editor guardian.co.uk, Sunday 15 July 2012 14.13 BST Virgin, the current holders of the west coast franchise, pay an annual premium of £150m to the government. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian FirstGroup has emerged as a frontrunner for the multibillion-pound west coast rail franchise alongside incumbent Virgin Trains, with the contest now a two-horse race between the experienced operators. Aberdeen-based FirstGroup is vying with Virgin despite announcing last year that it is handing back its Great Western rail contract three years ahead of schedule, avoiding more than £800m in payments to the government. The Department for Transport is expected to bank a considerable windfall from the new 14-year west coast contract, with Virgin currently paying an annual premium of about £150m to the state. Both bidders are expected to promise an even bigger number over the life of the new franchise. The winner is expected to be announced next month. It is understood that FirstGroup and Virgin are still in talks with the DfT, but two foreign-owned bidders on the four-strong shortlist are no longer considered likely contenders. They are a joint venture between public transport operator Keolis and SNCF, the French state rail group, and a bid from Abellio, which is controlled by the Dutch national rail operator. -

Issue 15 15 July 2005 Contents

RailwayThe Herald 15 July 2005 No.15 TheThe complimentarycomplimentary UKUK railway railway journaljournal forfor thethe railwayrailway enthusiastenthusiast In This Issue Silverlink launch Class 350 ‘Desiro’ New Track Machine for Network Rail Hull Trains names second ‘Pioneer’ plus Notable Workings and more! RailwayThe Herald Issue 15 15 July 2005 Contents Editor’s comment Newsdesk 3 Welcome to this weeks issue of All the latest news from around the UK network. Including launch of Class 350 Railway Herald. Despite the fact ‘Desiro’ EMUs on Silverlink, Hull Trains names second Class 222 unit and that the physical number of Ribblehead Viaduct memorial is refurbished. locomotives on the National Network continues to reduce, the variety of movements and operations Rolling Stock News 6 that occur each week is quite A brand new section of Railway Herald, dedicated to news and information on the astounding, as our Notable Workings UK Rolling Stock scene. Included this issue are details of Network Rail’s new column shows. Dynamic Track Stablizer, which is now being commissioned. The new look Herald continues to receive praise from readers across the globe - thank you! Please do feel free to pass the journal on to any friends or Notable Workings 7 colleagues who you think would be Areview of some of the more notable, newsworthy and rare workings from the past week interested. All of our back-issues are across the UK rail network. available from the website. We always enjoy hearing from readers on their opinions about the Charter Workings 11 journal as well as the magazine. The Part of our popular ‘Notable Workings’ section now has its own column! Charter aim with Railway Herald still Workings will be a regular part of Railway Herald, providing details of the charters remains to publish the journal which have worked during the period covered by this issue and the motive power. -

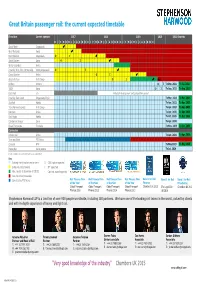

Great Britain Passenger Rail: the Current Expected Timetable

Great Britain passenger rail: the current expected timetable Franchise Current operator 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Onwards DJFMA MJJASONDJFMA MJJASONDJFMA MJJASOND South West Stagecoach West Midlands Govia East Midlands Stagecoach O I South Eastern Govia O I Wales & Borders Arriva InterCity W.C./W.C. Partnership Virgin/Stagecoach O I Cross Country Arriva OI Great Western First Group OI Apr. Chiltern Chiltern OITo Dec. 2021 To Jul. 2022 TSGN Govia O I To Sep. 2021 To Sep. 2023 East West n/a Potential development and competition period InterCity East Coast Stagecoach/Virgin To Mar. 2023 To Mar. 2024 ScotRail Abellio To Apr. 2022 To Apr. 2025 TransPennine Express First Group To Apr. 2023 To Apr. 2025 Northern Arriva To Apr. 2025 To Apr. 2026 East Anglia Abellio To Oct. 2025 To Oct. 2026 Caledonian Sleeper Serco To Apr. 2030 Essex Thameside Trenitalia To Nov. 2029 To Jun. 2030 Concession London Rail Arriva To Apr. 2024 To Apr. 2026 Tyne and Wear PTE Nexus Crossrail MTR To May 2023 To May 2025 MerseyRail Serco/Abellio To Jul. 2028 Based on publicly available information as at 1 April 2017 Key Existing franchise/concession term O OJEU notice expected Extension/direct award I ITT expected Max. length at discretion of DfT/TS Contract award expected New franchise/concession Operated by PTE Nexus Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Rail Finance Firm Band 1 for Rail Band 1 for Rail Band 1 for Rail of the Year of the Year of the Year of the Year Finance Franchising Global Transport Global Transport Global Transport Global Transport Chambers UK 2015 The Legal 500 Chambers UK 2017 Finance 2016 Finance 2015 Finance 2014 Finance 2013 UK 2016 Stephenson Harwood LLP is a law firm of over 900 people worldwide, including 150 partners. -

Competitive Tendering of Rail Services EUROPEAN CONFERENCE of MINISTERS of TRANSPORT (ECMT)

Competitive EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT Tendering of Rail Competitive tendering Services provides a way to introduce Competitive competition to railways whilst preserving an integrated network of services. It has been used for freight Tendering railways in some countries but is particularly attractive for passenger networks when subsidised services make competition of Rail between trains serving the same routes difficult or impossible to organise. Services Governments promote competition in railways to Competitive Tendering reduce costs, not least to the tax payer, and to improve levels of service to customers. Concessions are also designed to bring much needed private capital into the rail industry. The success of competitive tendering in achieving these outcomes depends critically on the way risks are assigned between the government and private train operators. It also depends on the transparency and durability of the regulatory framework established to protect both the public interest and the interests of concession holders, and on the incentives created by franchise agreements. This report examines experience to date from around the world in competitively tendering rail services. It seeks to draw lessons for effective design of concessions and regulation from both of the successful and less successful cases examined. The work RailServices is based on detailed examinations by leading experts of the experience of passenger rail concessions in the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands. It also -

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit Contents How to install ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Technical information ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Liveries .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Cab guide ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Keyboard controls ...................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Features .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Global System for Mobile Communication-Railway (GSM-R) ............................................................................. 18 Registering .......................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Deregistering - Method 1 ............................................................................................................................................ -

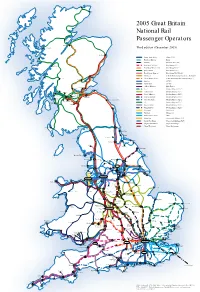

2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators Dingwall

Thurso Wick 2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators Dingwall Inverness Kyle of Lochalsh Third edition (December 2005) Aberdeen Arriva Trains Wales (Arriva P.L.C.) Mallaig Heathrow Express (BAA) Eurostar (Eurostar (U.K.) Ltd.) First Great Western (First Group P.L.C.) Fort William First Great Western Link (First Group P.L.C.) First ScotRail (First Group P.L.C.) TransPennine Express (First Group P.L.C./Keolis) Hull Trains (G.B. Railways Group/Renaissance Railways) Dundee Oban Crianlarich Great North Eastern (G.N.E.R. Holdings/Sea Containers P.L.C.) Perth Southern (GOVIA) Thameslink (GOVIA) Chiltern Railways (M40 Trains) Cardenden Stirling Kirkcaldy ‘One’ (National Express P.L.C.) North Berwick Balloch Central Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Gourock Milngavie Cumbernauld Gatwick Express (National Express P.L.C.) Bathgate Wemyss Bay Glasgow Drumgelloch Edinburgh Midland Mainline (National Express P.L.C.) Largs Berwick upon Tweed Silverlink Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Neilston East Kilbride Carstairs Ardrossan c2c (National Express P.L.C.) Harbour Lanark Wessex Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Chathill Wagn Railway (National Express P.L.C.) Merseyrail (Ned-Serco) Northern (Ned-Serco) South Eastern Trains (SRA) Island Line (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) South West Trains (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) Virgin CrossCountry (Virgin Rail Group) Virgin West Coast (Virgin Rail Group) Newcastle Stranraer Carlisle Sunderland Hartlepool Bishop Auckland Workington Saltburn Darlington Middlesbrough Whitby Windermere Battersby Scarborough -

Trains 27.1 15.0 3.7 1.8 North America - Continuing 22.6 20.6 18.3 17.8 Central Functions (4.7) (4.1) - - 67.3 53.2 6.2 4.6

Interim Results For the six months ended 30 June 2005 28 July 2005 Phil White Chief Executive HALF YEAR HIGHLIGHTS • Strong financial performance • Growth in earnings and dividend • Delivering premier league performance • Innovation driving passenger growth • Disposal of Public Transit to Connex • Record bid season in North America • Shareholder value enhanced Adam Walker Finance Director FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (1) • Strong financial results ¾ Margin improvement ¾ Costs controlled ¾ Cash flow generation ¾ Shareholder value • IFRS restatement presented in June FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (2) • Turnover £1.1bn (2004*: £1.2bn) • Normalised operating profit up 26.5% to £67.3m (2004*: £53.2m) • Normalised profit before tax of £58.1m up 47.5% (2004*: £39.4m) • Normalised diluted EPS of 31.3p up 44.9% (2004*: 21.6p) • Interim dividend of 10.0p up 7% (2004 : 9.35p) • Net debt of £143.3m (2004 : £136.6m) • Operating cash flow of £105.1m (2004 : £150.0m) * Restated under IFRS GROUP INCOME STATEMENT 2005 2004* £m £m Revenue 1,077.7 1,157.9 Normalised operating profit 67.3 53.2 Loss from associates (4.4) (4.3) Interest (4.8) (9.5) Normalised profit before tax 58.1 39.4 Exceptional items (0.3) (5.3) Goodwill & intangible asset amortisation (18.3) (17.2) Profit before tax 39.5 16.9 Taxation (14.7) (7.2) Profit after tax 24.8 9.7 (Loss)/Profit from discontinued operations (57.5) 4.6 (32.7) 14.3 * Restated under IFRS DIVISIONAL OPERATING PROFIT AND MARGIN Operating profit Operating margin 2005 2004* 2005 2004* £m £m % % Coaches 4.1 2.1 4.5 2.4 Buses 18.2 19.6 -

RC02 Electrification Paper

Electrification paper Introduction to the Rail Cluster Project The Rail Cluster Builder project was awarded to Scottish Engineering in August 2020 and is an 18-month programme funded by Scottish Enterprise and supported by Transport Scotland. The purpose of the project is to facilitate connections for SMEs in the engineering and manufacturing sectors in Scotland seeking to diversify into the rail market. The project is jointly funded by Scottish Enterprise and the 2014 – 2020 European Structural and Investment Fund through SPRITE (Scottish Programme for Research, Innovation and Technology Ecosystem). This is a small programme which aims to improve the innovation performance of Scotland’s Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) and stimulate greater coordination between stakeholders and partner organisations to help businesses capitalise on new economic and public sector innovation opportunities. The roots of the rail cluster project lie in the Rail Services Decarbonisation Plan in which the Scottish Government aims to decarbonise passenger rail services in Scotland by 2035, ahead of the UK’s target of 2040. By moving away from diesel and using green sources such as electricity, battery or hydrogen, opportunities will arise for innovation in train manufacturing as well as wider supply chains, supporting the creation of skilled, sustainable employment in Scotland. The Rail Cluster Builder will be key in helping to develop Scotland as a leader in the innovation and manufacture of net zero rail products and services. The UK government set out in June 2019 its legal commitment to achieve ‘net zero’ greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. In respect of the railway, in 2018 the DfT challenged the rail industry to remove all diesel-only trains from the network by 2040. -

Drivers'union

The train ASLEF drivers’ union >>> Rail Franchise Handbook 2019 ASLEF Introduction Welcome to our new Rail Franchise Handbook. I hope you will find it as interesting, and useful, as I do and a valuable tool for the political and industrial work you do for our union. We put this handbook together to give our reps and decision makers the inside track on who really runs Britain’s railways, how they run our railways, and what they take out from our railway industry every year. Because we believe the facts and figures revealed in these pages show, with crystal clarity, the utter folly of our privatised, and fragmented, franchise system. A structure – set up by John Major, 25 years ago, and continued by Conservative governments ever since – that separates the wheels and steel and is underwritten by an enormous public subsidy from every taxpayer in this country, and sky high passenger fares, while tens of millions of pounds haemorrhage from the system into the pockets of shareholders in the form of profits and dividends, or increasingly due inefficiencies. In fact whilst the system has never worked for passengers or taxpayers, there are now signs that it doesn’t work for operators either. The franchising system has been put on hold for a couple of years now due to a lack of bidders. This means direct awards have been handed out leading to even less competition. So we now have a system that exists to maintain the system itself, not our railway. It isn’t true to say that all the train and freight operating fill the pockets of shareholders; some TOCs and FOCs are owned by public, not private, operators where shareholders do not skim the cream off the top of the milk. -

Final Report Transport Scotland Strategic Transport Projects Review

Strategic Transport Projects Review Edinburgh – Glasgow Rail Improvements October 2007 Final Report Transport Scotland Strategic Transport Projects Review Authorisation Jacobs UK Ltd in association with Tribal Consulting has great pleasure in presenting this document. Copyright Jacobs U.K. Limited. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be copied or reproduced by any means without prior written permission from Jacobs U.K. Limited. If you have received this report in error, please destroy all copies in your possession or control and notify Jacobs U.K. Limited. This report has been prepared for the exclusive use of the commissioning party and unless otherwise agreed in writing by Jacobs U.K. Limited, no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of this report. No liability is accepted by Jacobs U.K. Limited for any use of this report, other than for the purposes for which it was originally prepared and provided. Opinions and information provided in the report are on the basis of Jacobs U.K. Limited using due skill, care and diligence in the preparation of the same and no warranty is provided as to their accuracy. It should be noted and it is expressly stated that no independent verification of any of the documents or information supplied to Jacobs U.K. Limited has been made. It should be noted that all timetables are indicative and require detailed work to prove that they can be planned and operated robustly. Authorisation & Preparation Prepared by: KMcK/GKD/ET Reviewed by: JM/GKD Approved by: JM / GKD Version History Version No. -

Meeting of the Parliament

MEETING OF THE PARLIAMENT Tuesday 24 February 2015 Session 4 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.scottish.parliament.uk or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Tuesday 24 February 2015 CONTENTS Col. TIME FOR REFLECTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 TOPICAL QUESTION TIME ................................................................................................................................... 3 Scottish Parliament Election 2016 (Votes for 16 and 17-year-olds) ............................................................. 3 LEGAL WRITINGS (COUNTERPARTS AND DELIVERY) (SCOTLAND) BILL: STAGE 3 ................................................. 8 Motion moved—[Fergus Ewing]. The Minister for Business, Energy and Tourism (Fergus Ewing) ................................................................. 8 Lewis Macdonald (North East Scotland) (Lab) ........................................................................................... 11 Annabel Goldie (West Scotland) (Con) ...................................................................................................... 13 Stewart Stevenson (Banffshire and Buchan Coast) (SNP) ........................................................................ 16 Margaret McCulloch (Central Scotland) (Lab) ...........................................................................................