DL4H Annexes 1-8.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

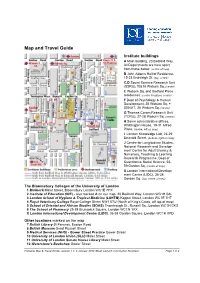

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

Education: Textbooks, Research and Initial Teacher Education

Education: tExtbooks, REsEaRch and initial tEachER Education 2013 continuum books aRE now publishEd undER bloomsbuRy VISIT THE NEW BLOOMSBURY WEBSITE www.bloomsbury.com/academic KEY FEATURES Bloomsbury’s complete range of academic titles, all in one place, by discipline Online previews of many titles Join in our online communities via blogs, twitter and facebook Sign up for our subject-specifi c newsletters FOR ACADEMICS FOR LIBRARIANS • Full inspection copy ordering service, including • Bloomsbury Academic Collections and Major NEW e-inspection copies Reference Work areas • Links to online resources and companion websites • Links to our Online Libraries, including Berg Fashion Library, The Churchill Archive and Drama Online • Discuss books, new research and current affairs on our subject-specifi c academic online communities • Information and subscription details for Bloomsbury Journals, including Fashion Theory, Food, Culture • Dedicated textbook and eBook areas and Society, The Design Journal and Anthrozoos FOR STUDENTS FOR AUTHORS • Links to online resources, such as bibliographies, • Information about publishing with Bloomsbury and author interviews, case studies and audio/video the publishing process materials • Style guidelines • Share ideas and learn about research and • Book and journal submissions information and key topics in your subject areas via our online proposals form communities • Recommended reading lists suggest key titles for student use Sign up for newsletters and to join our communities at: www.bloomsbury.com VISIT -

AMEE 2016 Final Programme

Saturday 27 August Saturday 27 August Pre-Conference Workshops Pre-registration is essential. Coffee will be provided. Lunch is not provided unless otherwise indicated Registration Desk / Exhibition 0745-1745 Registration Desk Open Exhibition Hall 0915-1215 PCW 01 Small Group Teaching with SPs: preparing faculty to manage student-SP simulations to enhance learning Tours – all tours depart and return to CCIB Lynn Kosowicz (USA), Diana Tabak (Canada), Cathy 0900-1400 In the Footsteps of Gaudí Smith (Canada), Jan-Joost Rethans (Netherlands), 0900-1400 Tour to Montserrat Henrike Holzer (Germany), Carine Layat Burn (Switzerland), Keiko Abe (Japan), Jen Owens (USA), Mandana Shirazi (Iran), Karen Reynolds (United Group Meetings Kingdom), Karen Lewis (USA) 1000-1700 AMEE Executive Committee M 213/214 - M2 Location: MR 121 – P1 Meeting (closed meeting) 0915-1215 PCW 02 The experiential learning feast around 0830-1700 WAVES Meeting M 215/216 - M2 non-technical skills (closed meeting) Peter Dieckmann (Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation – CAMES, Herlev, Denmark), Simon Edgar (NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, UK), Walter AMEE-Essential Skills in Medical Education (ESME) Courses Eppich (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Pre-registration is essential. Coffee & Lunch will be provided. Medicine, USA), Nancy McNaughton (University of Toronto, Canada), Kristian Krogh (Centre for Health 0830-1700 ESME – Essential Skills in Medical Education Sciences Education, Aarhus University, Denmark), Doris Location: MR 117 – P1 Østergaard (Copenhagen -

Curriculum Vitae

Professor Andrew Burn, curriculum vitae CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Andrew Nicholas Burn, PhD (London), MA (Oxon), MA (London), PGCE, FRSA [email protected] www.andrewburn.org present position Andrew Burn is Professor of English, Media and Drama at the UCL Institute of Education, University College London, based at the UCL Knowledge Lab. He is founder and director of the DARE collaborative for research into media arts, arts education and digital cultures and practices (www.darecollaborative.net), a UCL research centre and joint venture with the British Film Institute. He is director of MAGiCAL Projects, a games-based software enterprise (www.magicalprojects.co.uk). education and qualifications London University Institute of Education PhD (Film Semiotics) 1998 London University Institute of Education MA in Cultural Studies in Education (Distinction) 1995 Durham University PGCE (English and Drama) 1977 St John`s College, Oxford University BA/MA (Hons) Class II (English) 1975 career details Professor of English, Media and Drama Institute of Education 2014- Professor of Media Education Institute of Education 2009-14 Reader in Education and New Media Institute of Education 2006-9 Senior Lecturer in Media Education Institute of Education 2004-6 Lecturer in Media Education Institute of Education 2001-4 Assistant Principal Parkside Community College, Cambridge 1993-2001 Head of English/ Expressive Arts Parkside Community College 1986-93 Second in English Department Ernulf Community School, St Neots 1983-86 English Teacher St Peter`s School, Huntingdon -

ICME-13) 24 – 31 July 2016 in Hamburg

13th International Congress on Mathematical Education (ICME-13) 24 – 31 July 2016 in Hamburg Final Programme Joseph- Carlebach- Platz Binderstrasse Grindelhof Allende- Binderstrasse Platz H I Mensa Feldbrunnenstrasse Von- Melle- Audi- K Park G J max Johnsallee Mensa L F Schlüter E Grindelallee Bundesstrasse Staats- u. Universitäts- strasse Bibliothek Curio-Haus Feldbrunnenstrasse Hamburg D An der Verbindungsbahn Moorweidenstrasse Rothenbaumchaussee Flügel West D Uni-Haupt- Tier gebäude g art C e n s trasse Edmund-Siemers-Allee B Tesdorpfstr. PLANTEN UN BLOMEN MOOR- WEIDE Congress Parksee Centrum Flügel Hamburg A Ost Theodor- Heuss- A grey: Congress Center / CCH Platz B dark-brown: East Wing Building C turquoise: Main Building DAMMTOR D yellow: West Wing Building E mint: Economical Building F white: Campus MensaStraße G green: Social ScienceMarseiller Building STEPHANS- PLATZ H orange:Eingang Educational Building I blue:O st PhilosophicalBucerius Tower J red: AuditoriumJungiu LawSchool Maximum Alter Botanischer Kfenpurple: Law Building Teich Dammtordamm str Garten L pink: Main Mensa E Content Content Welcome to ICME-13 5 Committees of ICME-13 6 Congress Information / Overview 7 General Information 8 Opening and Closing Ceremony 14 Lectures of the ICMI awardees 15 Plenary Activities 16 Invited Lectures 20 ICMI Studies and Survey Teams 26 ICMI Affiliate Organisations 30 National Presentations 34 Thematic Afternoon 36 Topic Study Groups 44 Oral Communications 146 Poster 258 Discussion Groups 308 Workshops 326 Mathematical Exhibition 344 Early Career Researcher Day 345 Teachers’ Activities 348 For your notes 350 Sponsors and Supporters 355 Page 4 13th International Congress on Mathematical Education (ICME-13) · 24 – 31 July 2016 in Hamburg Welcome Welcome to ICME-13 The Society of Didactics of Mathematics (Gesellschaft für Didaktik der Mathematik – GDM) has the pleasure of hosting ICME-13 in 2016 in Germany. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Mathematics In

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 56/2014 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2014/56 Mathematics in Undergraduate Study Programs: Challenges for Research and for the Dialogue between Mathematics and Didactics of Mathematics Organised by Rolf Biehler, Paderborn Reinhard Hochmuth, Hannover Dame Celia Hoyles, London Patrick W. Thompson, Tempe 7 December – 13 December 2014 Abstract. The topic of undergraduate mathematics is of considerable con- cern for mathematicians in universities, but also for those teaching mathemat- ics as part of undergraduate studies other than mathematics, for employers seeking to employ a mathematically skilled workforce, and for teacher edu- cation. Different countries have made and continue to make massive efforts to improve the quality of mathematics education across all age ranges, with most of the research undertaken particularly at the school level. A growing number of mathematicians and mathematics educators now see the need for undertaking interdisciplinary research and collaborative reflections around issues at the tertiary level. The conference aimed to share research results and experiences as a background to establishing a scientific community of mathematicians and mathematics educators whose concern is the theoreti- cal reflection, the research-based empirical investigation, and the exchange of best-practice examples of mathematics education at the tertiary level. The focus of the conference was mathematics education for mathematics, engi- neering and economy majors and for future mathematics teachers. -

How Affect-Aware Feedback Can Improve Student Learning

Affecting Off-Task Behaviour: How Affect-aware Feedback Can Improve Student Learning Beate Grawemeyer Manolis Mavrikis Wayne Holmes London Knowledge Lab London Knowledge Lab London Knowledge Lab Birkbeck, University of London UCL Institute of Education UCL Institute of Education London, UK University College London, UK University College London, UK [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Sergio Gutierrez-Santos Michael Wiedmann Nikol Rummel London Knowledge Lab Institute of Educational Institute of Educational Birkbeck, University of London Research Research London, UK Ruhr-Universität Bochum, DE Ruhr-Universität Bochum, DE [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords This paper describes the development and evaluation of an Affect, Feedback, Exploratory Learning Environments affect-aware intelligent support component that is part of a learning environment known as iTalk2Learn. The intelligent support component is able to tailor feedback according to a 1. INTRODUCTION student’s affective state, which is deduced both from speech The aim of our research is to provide intelligent support to and interaction. The affect prediction is used to determine students, taking into account their affective states in order which type of feedback is provided and how that feedback to enhance their learning experience and performance. is presented (interruptive or non-interruptive). The system It is well understood that affect interacts with and in- includes two Bayesian networks that were trained with data fluences the learning process [19, 10, 3]. While positive gathered in a series of ecologically-valid Wizard-of-Oz stud- affective states (such as surprise, satisfaction or curiosity) ies, where the effect of the type of feedback and the presen- contribute towards learning, negative ones (including frus- tation of feedback on students’ affective states was investi- tration or disillusionment at realising misconceptions) can gated. -

Learning Progression in Secondary Students' Digital Video Production

Learning progression in secondary students' digital video production Stephen Connolly London Knowledge Lab, Institute of Education, University of London This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 I hereby declare that, except where explicit attribution is made, the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. 86,000 words (rounding to the nearest thousand and excluding bibliography, references and appendices) ABSTRACT OF THESIS Assessing learning progression in Media Education is an area of study which has been largely neglected in the history of the subject, with very few longitudinal studies of how children learn to become "media literate" over an extended period of time. This thesis is an analysis of data over three years (constituted by the production of digital video work by a small group of secondary school students) which attempts to offer a more extended account of this learning. The thesis views the data through three concepts (or "lenses") which have been key to the development of media education in the UK and abroad. These are Culture, Criticality and Creativity, and the theoretical perspectives that the thesis should be viewed in the light of include the work of Bourdieu, Vygotsky, Heidegger and Hegel. The examination of the student production work carried out in the light of these three lenses suggests that learning progression comes about because of a relationship between all three, the key metaphorical idea put forward by the thesis that describes that relationship is the dialectic of familiarity. This suggests that for media education at least, the learning process is a dialectic one, in which students move from cultural and critical knowledge and experiences that are familiar -or thetic - to ones that are unfamiliar, and hence antithetical. -

Computer Science at Birkbeck College

School of Computer Science & Information Systems A Short History Greetings from our founders, Andrew and Kathleen Booth Kathleen and I send our greetings and best wishes to the students and Faculty of the Department of Computer Science at Birkbeck on the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the department in 1957. We wish that we could be with you but constraints of age and health make this impossible. You may like to know that the original department was responsible for building one of the first operational computers in the World, the APEXC and its successors, the M series and the commercial version the HEC machines sold by the then ICT of which over 120 were produced. Having produced the machines we needed teaching material and so produced the first systematic books on modern numerical analysis, programming and computer design. On the research side we started research on Machine Translation, on thin film storage technology for digital storage, and magnetic drum and disc storage. Braille transcription, now touted as a recent IBM invention was actually the work of one of our Ph.D. students. And genetic, self modifying programs were also invented here. These are only a few of our original activities and you are the carriers of a distinguished origin. Kathleen and I (and the late Dr. J.C. Jennings the other member of the original faculty) send you our best wishes for the future. I do not expect to be with you in body in 2058 but I shall be with you in spirit. Andrew & Kathleen Booth Vancouver Island, BC, Canada April 2008 1. -

The London Mathematical Society

THE LONDON MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER No. 397 November 2010 Society 2010 ELECTIONS Committee for potential candi- Meetings dates for the 2011 elections was TO COUNCIL AND also included with the October and Events NOMINATING Newsletter. Members are also able to make direct nominations; 2010 COMMITTEE details will be given in the April Friday 19 November The ballot papers for the No- and May Newsletter next year. Annual General vember elections to Council and Meeting and Naylor Nominating Committee were cir- ANNUAL GENERAL Lecture, London culated with the October News- MEETING [pages 3] letter. Nominating Committee put forward names for each The Annual General Meeting of Monday 6 December Officer post; in addition mem- the Society will be held at 3.5 Society Meeting, bers proposed a further candi- pm on Friday 9 November 200 ICMS, Edinburgh date for the Education Secretary at University College London. [page 5] post. A total of nine candidates The business shall be: have been proposed (eight by (i) the adoption of the Annual 2011 Nominating Committee, one by Report for 2009/0 Friday 25 February members) for the six vacancies of (ii) the report of the Treasurer Mary Cartwright Members-at-Large of Council. (iii) appointment of Auditors Lecture, Oxford Four names have been proposed (iv) elections to Council and [page 3] (all by Nominating Committee) for Nominating Committee two vacancies in the membership (v) presentation of certificates Friday 6 May of the Nominating Committee. to LMS prizewinners Women in Mathematics Please note that completed It is hoped that as many members Day, London ballot papers must be returned as possible will be able to attend. -

LLAKES Newsletterissue 1, Winter 2009

LLAKES NewsletterIssue 1, Winter 2009 WELCOME from LLAKES Centre Director, Contents Andy Green Centre Director’s Welcome 1 Welcome to our first newsletter. The LLAKES Centre News 2 LLAKES Centre was established LLAKES Centre Launch, House of Commons in January 2008 with a five-year grant from the Economic and Social Higher Apprenticeships in Italy Research Council (ESRC). Its brief Apprenticeships Bill is to conduct research on the role of lifelong learning in promoting Researching Family and Friendship-Based economic competitiveness and social Inter- Generational Networks: Qualitative Perspectives cohesion. Unlike existing ESRC centres which focus on either Ingrid Schoon Journal Article Published economic or social outcomes, LLAKES will investigate the inter-relations between the two, including identifying learning Lifelong Learning Peer Reviews of Regions policies and practices which can help mediate sometimes LLAKES Centre Publications antagonistic economic and social objectives. In addition to its research role, LLAKES is also providing capacity building for Reviews and Comment 4 researchers and policy-makers. This will focus on the use of OECD Report: Growing Unequal? international data and mixed-method comparative analysis in reviewed by Ann Doyle the development of evidence-based lifelong learning policies for competitiveness and cohesion. Social Cohesion Policy Documents in the UK: An Overview, by Christine Han We are fortunate to have recruited five talented new researchers: Dr Helen Cheng, Dr Bryony Hoskins, Indicators for active citizenship in Europe, Magdalini Kolokitha, Dr Sadaf Rizvi and Tarek Mostafa. by Bryony Hoskins They now work at the IOE and join the existing team of four LLAKES Centre Researchers Appointed 9 researchers and eighteen permanent academic staff who conduct research in LLAKES at the IOE and its partner The LLAKES Research Programme 10 institutions, the Universities of Bristol and Southampton and Past LLAKES Events 11 the National Institute of Economic and Social Research. -

Decoding Learning: the Proof, Promise and Potential of Digital Education

DECODING LEARNING: THE PROOF, PROMISE AND POTENTIAL OF DIGITAL EDUCATION Rosemary Luckin, Brett Bligh, Andrew Manches, Shaaron Ainsworth, Charles Crook, Richard Noss November 2012 About Nesta Nesta is the UK’s innovation foundation. We help people and organisations bring great ideas to life. We do this by providing investments and grants and mobilising research, networks and skills. We are an independent charity and our work is enabled by an endowment from the National Lottery. Nesta Operating Company is a registered charity in England and Wales with company number 7706036 and charity number 1144091. Registered as a charity in Scotland number SC042833. Registered office: 1 Plough Place, London, EC4A 1DE www.nesta.org.uk © Nesta 2012. 3 THE PROOF, PROMISE AND POTENTIAL OF DIGITAL EDUCATION CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHORS 5 FOREWORD 6 AUTHORS’ ACKNOWLEDGEMENts 7 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION AND SCENE SETTING 8 CONDUCTING THE REVIEW 10 CHAPTER 2: LEARNING WITH TECHNOLOGY 14 LEARNING FROM EXPERTS 15 LEARNING WITH OtHERS 19 LEARNING THROUGH MAKING 24 LEARNING THROUGH EXPLORING 28 LEARNING THROUGH INQUIRY 32 LEARNING THROUGH PRACTISING 36 LEARNING FROM ASSESSMENT 39 LEARNING IN AND ACROSS SETTINGS 43 CHAPTER 3: BRINGING LEARNING TOGETHER 47 LINKING LEARNING ACTIVITIES 48 LINKING AT THE INSTITUTIONAL LEVEL 50 CHAPTER 4: CONTEXT IS IMPORTANT 53 ENVIRONMENT 54 KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS 55 PEOPLE 55 TOOLS 56 4 THE PROOF, PROMISE AND POTENTIAL OF DIGITAL EDUCATION CHAPTER 5: BRINGING RESEARCH INTO REALITY 59 LEARNING FROM THE EVIDENCE 59 KEY PRIORITIES FOR TECHNOLOGY IN LEARNING 61 CONCLUSION 63 APPENDICES 65 APPENDIX 1: TABLE OF INFORMATION SOURCES 65 APPENDIX 2: THE ADAPTIVE COMPARATIVE JUDGEMENT (ACJ) METHOD 66 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 ENDNOTES 86 5 THE PROOF, PROMISE AND POTENTIAL OF DIGITAL EDUCATION ABOUT THE AUTHORS Professor Rosemary Luckin from the London Knowledge Lab has a background in Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence.