Decoding Learning: the Proof, Promise and Potential of Digital Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hirsh-Pasek Vita 2-21

Date: February, 2021 Kathryn A. Hirsh-Pasek, Ph.D. The Debra and Stanley Lefkowitz Distinguished Faculty Fellow Senior Fellow Brookings Institution Academic Address Department of Psychology Temple University Philadelphia, PA 19122 (215) 204-5243 [email protected] twitter: KathyandRo1 Education University of Pennsylvania, Ph.D., 1981 (Human Development/Psycholinguistics) University of Pittsburgh, B.S., 1975 (Psychology/Music) Manchester College at Oxford University, Non-degree, 1973-74 (Psychology/Music) Honors and Awards Placemaking Winner, the Real Play City Challenge, Playful Learning Landscapes, November 2020 AERA Fellow, April 2020 SIMMS/Mann Whole Child Award, October 2019 Fellow of the Cognitive Science Society, December 2018 IDEO Award for Innovation in Early Childhood Education, June 2018 Outstanding Public Communication for Education Research Award, AERA, 2018 Living Now Book Awards, Bronze Medal for Becoming Brilliant, 2017 Society for Research in Child Development Distinguished Scientific Contributions to Child Development Award, 2017 President, International Congress on Infant Studies, 2016-2018 APS James McKeen Cattell Fellow Award - “a lifetime of outstanding contributions to applied psychological research” – 2015 Distinguished Scientific Lecturer 2015- Annual award given by the Science Directorate program of the American Psychological Association, for three research scientists to speak at regional psychological association meetings. President, International Congress on Infant Studies – 2014-2016 NCECDTL Research to Practice Consortium Member 2016-present Academy of Education, Arts and Sciences Bammy Award Top 5 Finalist “Best Education Professor,” 2013 Bronfenbrenner Award for Lifetime Contribution to Developmental Psychology in the service of science and society. August 2011 Featured in Chronicle of Higher Education (February 20, 2011): The Case for play. Featured in the New York Times (January 5, 2011) Effort to Restore Children’s Play Gains Momentum (article on play and the Ultimate Block Party; most emailed article of the day). -

Vtech/Leapfrog Consumer Research

VTech/LeapFrog consumer research Summary report Prepared For: Competition & Markets Authority October 2016 James Hinde Research Director Rebecca Harris Senior Research Manager 3 Pavilion Lane, Strines, Stockport, Cheshire, SK6 7GH +44 (0)1663 767 857 Page 1 djsresearch.co.uk Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 3 Background & Methodology ........................................................................................... 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 Research Objectives .................................................................................................. 5 Sample .................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 7 Reporting ............................................................................................................... 10 Profile of participants .................................................................................................. 11 Purchase context, motivations and process ................................................................... 24 Diversion behaviour ................................................................................................... -

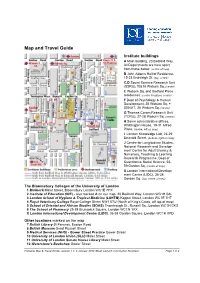

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

The Role of Play and Direct Instruction in Problem Solving in 3 to 5 Year Olds

THE ROLE OF PLAY AND DIRECT INSTRUCTION IN PROBLEM SOLVING IN 3 TO 5 YEAR OLDS Beverly Ann Keizer B. Ed. , University of British Columbia, 1971 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (EDUCATION) in the Faculty of Education @Beverly Ann Keizer 1983 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY March 1983 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author APPROVAL Name : Beverly Ann Keizer Degree : Master of Arts (Education) Title of Thesis: The Role of Play and Direct Instruction in Problem Solving in 3 to 5 Year Olds Examining Committee Chairman : Jack Martin Roger Gehlbach Senior Supervisor Ronald W. Marx Associate Professor Mary Janice partridge Research Evaluator Management of Change Research Project Children's Hospital Vancouver, B. C. External Examiner Date approved March 14, 1983 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University L ibrary, and to make part ial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Stem/Steam Formula for Success

STEM/STEAM FORMULA FOR SUCCESS The Toy Association STEM/STEAM Formula for Succcess 1 INTRODUCTION In 2017, The Toy Association began to explore two areas of strong member interest: • What is STEM/STEAM and how does it relate to toys? • What makes a good STEM/STEAM toy? PHASE I of this effort tapped into STEM experts and focused on the meaning and messages surrounding STEM and STEAM. To research this segment, The Toy Association reached out to experts from scientific laboratories, research facilities, professional associations, and academic environments. Insights from these thought leaders, who were trailblazers in their respective field of science, technology, engineering, and/or math, inspired a report detailing the concepts of STEM and STEAM (which adds the “A” for art) and how they relate to toys and play. Toys are ideally suited to developing not only the specific skills of science, technology, engineering, and math, but also inspiring children to connect to their artistic and creative abilities. The report, entitled “Decoding STEM/STEAM” can be downloaded at www.toyassociation.org. In PHASE 2 of this effort, The Toy Association set out to define the key unifying characteristics of STEM/STEAM toys. Before diving into the characteristics of STEM/STEAM toys, we wanted to take the pulse of their primary purchaser—parents of young children. The “Parents’ Report Card,” is a look inside the hopes, fears, frustrations, and aspirations parents have surrounding STEM careers and STEM/STEAM toys. Lastly, we turned to those who have dedicated their careers to creating toys by tapping into the expertise of Toy Association members. -

Education: Textbooks, Research and Initial Teacher Education

Education: tExtbooks, REsEaRch and initial tEachER Education 2013 continuum books aRE now publishEd undER bloomsbuRy VISIT THE NEW BLOOMSBURY WEBSITE www.bloomsbury.com/academic KEY FEATURES Bloomsbury’s complete range of academic titles, all in one place, by discipline Online previews of many titles Join in our online communities via blogs, twitter and facebook Sign up for our subject-specifi c newsletters FOR ACADEMICS FOR LIBRARIANS • Full inspection copy ordering service, including • Bloomsbury Academic Collections and Major NEW e-inspection copies Reference Work areas • Links to online resources and companion websites • Links to our Online Libraries, including Berg Fashion Library, The Churchill Archive and Drama Online • Discuss books, new research and current affairs on our subject-specifi c academic online communities • Information and subscription details for Bloomsbury Journals, including Fashion Theory, Food, Culture • Dedicated textbook and eBook areas and Society, The Design Journal and Anthrozoos FOR STUDENTS FOR AUTHORS • Links to online resources, such as bibliographies, • Information about publishing with Bloomsbury and author interviews, case studies and audio/video the publishing process materials • Style guidelines • Share ideas and learn about research and • Book and journal submissions information and key topics in your subject areas via our online proposals form communities • Recommended reading lists suggest key titles for student use Sign up for newsletters and to join our communities at: www.bloomsbury.com VISIT -

ED 043 305 PUP DATE Enrs PRICE DOCUMENT RESUME

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 043 305 HE 001 /76 TTTLr The Trustee; A Key to Progress in the Small College. TNSTITUTION Council for the Advancement of Small Colleges, Vashinaton, D.C. PUP DATE [101 NOTE 164p.: Papers presented at an Institute for trustees and administrators of small colleges, Michigan State nniversity, Fast Lansina, Michigan, August, 196c' EnRs PRICE FDES Price 4F-$0.15 FC-5B.30 OESCRIPTORS *Administrator Role, College Administration, Educational Finance, Governance, *Governing aoards, *Nigher Fducation, Leadership Responsibility, Planning, *Ic.sponsibilltv, *Trustees IOSTRACT The primary pw:pose of the institute was to give members (IC the board of trustees of small colleges a better understanding of their proper roles and functions. The emphasis was on increasing the effectiveness of the trustee, both in his general relationship to the college and in his working and policy-formulating relationship to the president and other top-level cdministralors. This boo}- presents the rapers delivered during the week -long program: "College Trusteeship, 1069," by Myron F. Wicket "Oporational Imperatives for a College Poari of Trustees in the 1910s," by Arthur C. rrantzreb; "A Trustee Examines "is Role," by warren M. "uff; "The College and university Student Today," by Richall F. Gross; "The College Student Today," by Eldon Nonnamaker; "Today's l'aculty Member,'' by Peter °prevail; "The Changing Corricilum: Implications for the Small College," by G. tester Pnderson; "How to get the 'lowly," by Gordon 1. Caswell; "Founflations and the Support of ?nigher rduPation," by Manning M.Pattillo; "The Trustee and Fiscal Develorment," by 0ohn R. Haines; "tong-Range Plannina: An Fs.ential in College Administration," by Chester M.Alter; and "Trustee-Presidential Relationships," by Roger J. -

A Strategic Audit of Oriental Trading Company Isaac Coleman University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Spring 2019 A Strategic Audit of Oriental Trading Company Isaac Coleman University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Business Commons Coleman, Isaac, "A Strategic Audit of Oriental Trading Company" (2019). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 150. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/150 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A STRATEGIC AUDIT OF ORIENTAL TRADING COMPANY An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln By Isaac Coleman Computer Science College of Arts and Sciences April 7, 2019 Faculty Mentor: Samuel Nelson, Ph.D., Center for Entrepreneurship ABSTRACT Oriental Trading Company is a direct marketer and seller of toys, novelties, wedding favors, custom apparel, and other event supplies. Its products are sold by five brands, each of which participates in a different market. Though its flagship brand, Oriental Trading, is a powerful market leader in novelties and is doing extremely well, the four most recent brands each face distinct challenges and have low name recognition. To increase name recognition and direct sales of these brands, this audit proposes that OTC revitalize its social media presence, add a blog to all of its websites, and resume public participation in local events. -

AMEE 2016 Final Programme

Saturday 27 August Saturday 27 August Pre-Conference Workshops Pre-registration is essential. Coffee will be provided. Lunch is not provided unless otherwise indicated Registration Desk / Exhibition 0745-1745 Registration Desk Open Exhibition Hall 0915-1215 PCW 01 Small Group Teaching with SPs: preparing faculty to manage student-SP simulations to enhance learning Tours – all tours depart and return to CCIB Lynn Kosowicz (USA), Diana Tabak (Canada), Cathy 0900-1400 In the Footsteps of Gaudí Smith (Canada), Jan-Joost Rethans (Netherlands), 0900-1400 Tour to Montserrat Henrike Holzer (Germany), Carine Layat Burn (Switzerland), Keiko Abe (Japan), Jen Owens (USA), Mandana Shirazi (Iran), Karen Reynolds (United Group Meetings Kingdom), Karen Lewis (USA) 1000-1700 AMEE Executive Committee M 213/214 - M2 Location: MR 121 – P1 Meeting (closed meeting) 0915-1215 PCW 02 The experiential learning feast around 0830-1700 WAVES Meeting M 215/216 - M2 non-technical skills (closed meeting) Peter Dieckmann (Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation – CAMES, Herlev, Denmark), Simon Edgar (NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, UK), Walter AMEE-Essential Skills in Medical Education (ESME) Courses Eppich (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Pre-registration is essential. Coffee & Lunch will be provided. Medicine, USA), Nancy McNaughton (University of Toronto, Canada), Kristian Krogh (Centre for Health 0830-1700 ESME – Essential Skills in Medical Education Sciences Education, Aarhus University, Denmark), Doris Location: MR 117 – P1 Østergaard (Copenhagen -

Schools at a Glance Cambridge Public Schools 2020 – 21 School District Childhood Early

Schools at a Glance CAMBRIDGE PUBLIC SCHOOLS 2020 – 21 School District School Childhood Early Rigorous, Joyful & Culturally Elementary Responsive Learning and Schools Personalized Support Schools Upper School High Resources SUPERINTENDENT’S WELCOME Dear Families & Community, It is my great honor and privilege to welcome you to Cambridge Public Schools (CPS) - a vibrant, diverse, and inclusive school community. In the midst of the global pandemic, the CPS community - including students, educators, families, and staff - have demonstrated great resilience, flexibility, creativity and strength. CPS’s shared vision of providing a rigorous, joyful and culturally responsive learning experience and personalized support for every student is even more important in the current context, when every student may need something different to be successful. CPS also continues its journey to become an actively anti-racist school district and organization, by working towards instilling inclusive principles across our hiring and retention practices for staff, culturally responsive teaching and learning for students, and meaningful partnership with our families, out-of-school time partners, and community members. In this Schools-at-a-Glance, you’ll find information about our schools, programs, and key contacts to help you navigate your journey with CPS. We greatly value our relationship with families as we work together to support our students academic, social, emotional, and developmental needs. We look forward to many years of collaboration and partnership. Thank you and welcome to the CPS family! Sincerely, Kenneth N. Salim, Ed.D. Superintendent Disclaimer: Information presented in Schools at a Glance refers to normal operating procedures. Some information may differ during the 2020-21 school year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. -

Parent-Child Home Program, Garden City, NY WHO THEY ARE

Parent-Child Home Program, Garden City, NY WHO THEY ARE The Parent-Child Home Program: Parent-Child Home Program (PCHP) focuses on a gentle lesson for parents • Uses home visits to strengthen and guardians seeking to prepare young children for school: Sit down with your child, and a book or a toy, and have fun. parent-child verbal interaction and reading and play activities that help “When it’s fun for the child, that’s when they really learn,” says Merl Chavis, a children learn. home visitor in the PCHP program at SCO Family of Services, a Brooklyn social • Reaches 6,750 families: service agency. 30% African American, 30% Hispanic, 30% Caucasian, 10% PCHP began 45 years ago, when Phyllis Levenstein, then a doctoral student at Asian immigrant and other Columbia Teachers College, developed the program model to reduce high immigrant populations. school dropout rates by working with low-income parents before their children • 38% of parents/caregivers in U.S. ever entered school. Now headquartered in Garden City, N.Y. on Long Island, PCHP partners with local school districts, charter schools, social service less than 10 years. agencies, hospitals and community health centers, public libraries and • Annual income of families served: universities to set up program sites and reach out to families. 45% less than $10,000. 84% less than $30,000. Parents and guardians sign up for the two-year program when their children are • Average annual cost per family: two-years-old. From fall through spring, a PCHP home visitor then comes to the $2,800 (ranges from $1,500 to family’s home for a half-hour, twice weekly, to meet with the parent or guardian $4,500 depending on a site’s and the child. -

The Use of Educational Toys by Parents of Children with Intellectual

G.J.I.S.S.,Vol.4(6):35-39 (November-December, 2015) ISSN: 2319-8834 The Use of Educational Toys by Parents of Children with Intellectual Disabilities Sri Sumijati & Rustina Untari Soegijapranata Catholic University, Semarang, Indonesia Abstract Children with intellectual disabilities understand and learn things in relatively slower pace compared to their peer, so they need stimulation from various ways and means in order to develop optimally. Educational toys (ET) are the best learning tools for children with intellectual disabilities. Parents as a natural educator for children have an important role in their children early stimulation. The problem is, have said parents already used ET to stimulate their children’s development? Twenty six parents of children with intellectual disabilities were answering that in this study. Result showed that there were four categories regarding ET use by the parents, which were 1) parents who aware and consistently using ET to stimulate their children’s development, 2) parents who seldom using ET for various reasons, 3) parents who didn’t actually aware of ET but using it, and 4) parents who never used ET at all. Keywords: children with intellectual disability, educational toy (ET), parent 1. Introduction According to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (APA, 2013) intellectual disability or intellectual development disorder is a disorder in intellectual function which occur since the developmental age. Children with intellectual disabilities usually have difficulties in reasoning, problem solving, planning, abstract thinking, decision making, academic learning and experimental learning. Considering these difficulties children with intellectual disabilities are having, certain teaching method is needed in order to optimize their development.