Borderless 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map and Travel Guide

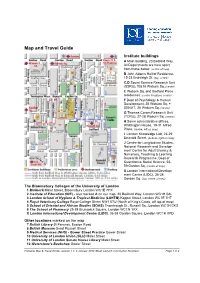

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

Education: Textbooks, Research and Initial Teacher Education

Education: tExtbooks, REsEaRch and initial tEachER Education 2013 continuum books aRE now publishEd undER bloomsbuRy VISIT THE NEW BLOOMSBURY WEBSITE www.bloomsbury.com/academic KEY FEATURES Bloomsbury’s complete range of academic titles, all in one place, by discipline Online previews of many titles Join in our online communities via blogs, twitter and facebook Sign up for our subject-specifi c newsletters FOR ACADEMICS FOR LIBRARIANS • Full inspection copy ordering service, including • Bloomsbury Academic Collections and Major NEW e-inspection copies Reference Work areas • Links to online resources and companion websites • Links to our Online Libraries, including Berg Fashion Library, The Churchill Archive and Drama Online • Discuss books, new research and current affairs on our subject-specifi c academic online communities • Information and subscription details for Bloomsbury Journals, including Fashion Theory, Food, Culture • Dedicated textbook and eBook areas and Society, The Design Journal and Anthrozoos FOR STUDENTS FOR AUTHORS • Links to online resources, such as bibliographies, • Information about publishing with Bloomsbury and author interviews, case studies and audio/video the publishing process materials • Style guidelines • Share ideas and learn about research and • Book and journal submissions information and key topics in your subject areas via our online proposals form communities • Recommended reading lists suggest key titles for student use Sign up for newsletters and to join our communities at: www.bloomsbury.com VISIT -

AMEE 2016 Final Programme

Saturday 27 August Saturday 27 August Pre-Conference Workshops Pre-registration is essential. Coffee will be provided. Lunch is not provided unless otherwise indicated Registration Desk / Exhibition 0745-1745 Registration Desk Open Exhibition Hall 0915-1215 PCW 01 Small Group Teaching with SPs: preparing faculty to manage student-SP simulations to enhance learning Tours – all tours depart and return to CCIB Lynn Kosowicz (USA), Diana Tabak (Canada), Cathy 0900-1400 In the Footsteps of Gaudí Smith (Canada), Jan-Joost Rethans (Netherlands), 0900-1400 Tour to Montserrat Henrike Holzer (Germany), Carine Layat Burn (Switzerland), Keiko Abe (Japan), Jen Owens (USA), Mandana Shirazi (Iran), Karen Reynolds (United Group Meetings Kingdom), Karen Lewis (USA) 1000-1700 AMEE Executive Committee M 213/214 - M2 Location: MR 121 – P1 Meeting (closed meeting) 0915-1215 PCW 02 The experiential learning feast around 0830-1700 WAVES Meeting M 215/216 - M2 non-technical skills (closed meeting) Peter Dieckmann (Copenhagen Academy for Medical Education and Simulation – CAMES, Herlev, Denmark), Simon Edgar (NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, UK), Walter AMEE-Essential Skills in Medical Education (ESME) Courses Eppich (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Pre-registration is essential. Coffee & Lunch will be provided. Medicine, USA), Nancy McNaughton (University of Toronto, Canada), Kristian Krogh (Centre for Health 0830-1700 ESME – Essential Skills in Medical Education Sciences Education, Aarhus University, Denmark), Doris Location: MR 117 – P1 Østergaard (Copenhagen -

Curriculum Vitae

Professor Andrew Burn, curriculum vitae CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Andrew Nicholas Burn, PhD (London), MA (Oxon), MA (London), PGCE, FRSA [email protected] www.andrewburn.org present position Andrew Burn is Professor of English, Media and Drama at the UCL Institute of Education, University College London, based at the UCL Knowledge Lab. He is founder and director of the DARE collaborative for research into media arts, arts education and digital cultures and practices (www.darecollaborative.net), a UCL research centre and joint venture with the British Film Institute. He is director of MAGiCAL Projects, a games-based software enterprise (www.magicalprojects.co.uk). education and qualifications London University Institute of Education PhD (Film Semiotics) 1998 London University Institute of Education MA in Cultural Studies in Education (Distinction) 1995 Durham University PGCE (English and Drama) 1977 St John`s College, Oxford University BA/MA (Hons) Class II (English) 1975 career details Professor of English, Media and Drama Institute of Education 2014- Professor of Media Education Institute of Education 2009-14 Reader in Education and New Media Institute of Education 2006-9 Senior Lecturer in Media Education Institute of Education 2004-6 Lecturer in Media Education Institute of Education 2001-4 Assistant Principal Parkside Community College, Cambridge 1993-2001 Head of English/ Expressive Arts Parkside Community College 1986-93 Second in English Department Ernulf Community School, St Neots 1983-86 English Teacher St Peter`s School, Huntingdon -

2013 EAIE ANNUAL REPORT 2012-2014 EAIE Leadership

2013 EAIE ANNUAL REPORT 2012-2014 EAIE Leadership EAIE Annual Report 2013 03 Letter from the EAIE President 04 Letter from the EAIE Executive Director 05 Annual Conference 07 The EAIE Academy 08 Publishing 09 EAIE in the field 10 Member services 11 Financial report 12 Expert communities 14 Thank you 02 POSITIONING THE EAIE FOR MORE DYNAMIC PARTNERSHIPS HANS-GEORG VAN LIEMPD EAIE PRESIDENT The year 2013 was significant for the EAIE, with the 25th Annual EAIE Conference in Istanbul symbolising not only the EAIE’s outward looking orientation, but our commitment to developing a platform for creating dynamic partnerships. With internationalisation policies being increasingly driven by institutional leadership, the EAIE established, jointly with the International Association of Universities (IAU), an exclusive Executive Programme for Vice Chancel- lors, Presidents and Rectors within the scope of the EAIE conference, with The structure of the the aim of enhancing the EAIE’s visibility among decision-makers and General Council was important stakeholders. changed to consist of 14 directly elected Additionally this year, the EAIE partnered with the Association of members and the International Education Administrators (AIEA) on the Leadership Immediate Past Professional Sections President. and Special Interest Roundtable, giving senior professionals the opportunity to discuss key Groups were converted leadership issues. The programme will continue in 2014 in Brno, Czech to Expert Communities Republic, just prior to the EAIE Annual Conference in Prague. The EAIE published Phase II of the research project with the Inter- national Education Association of Australia (IEAA), known as the ‘Leadership Study’, followed by a final report in January 2014. -

Open Forum Debate on "University Democracy”

Open Forum Debate On "University Democracy” At the Duisburg-Essen Aurora Biannual – 2, 3 May 2018 Introduction Aurora is a network of engaged research universities that aim to match academic excellence with societal relevance: in education, research, and service to the society. At the Aurora Biannual meetings, a plenary session is the stage of an Open Forum Debate on a topic of relevance to the Aurora universities and also outside the network. After Debates on the role of the university in a post-truth society (Reykjavik, May 2017) and on the Humanities & Social Sciences (Norwich, November 2017), the Duisburg-Essen Aurora Biannual will host an Open Forum Debate on University Democracy on May 3rd, in the Glaspavillon, Essen Campus, University of Duisburg-Essen. On the topic University democracy can and does mean very different things in different higher education systems in Europe. The level of autonomy granted to universities differs. Aurora universities are subject to different governance traditions and legal frameworks: some universities work in a corporate framework (e.g. UEA and VUA), while many of the others work in a framework of elected leadership. Within these systems, various internal stakeholders like professors, other academics, students and non/academic staff may have different formal mandates. Independent of the formal mandate, tradition may give some stakeholders a stronger or weaker influence in practice than their official mandate shows. In addition – and partly reflecting this – Aurora universities operate in political systems that are more strongly leaning towards liberal market economy principles, while others operate more in a Rhineland-like stakeholder consensus model and/or a university-as-public-good paradigm. -

ICME-13) 24 – 31 July 2016 in Hamburg

13th International Congress on Mathematical Education (ICME-13) 24 – 31 July 2016 in Hamburg Final Programme Joseph- Carlebach- Platz Binderstrasse Grindelhof Allende- Binderstrasse Platz H I Mensa Feldbrunnenstrasse Von- Melle- Audi- K Park G J max Johnsallee Mensa L F Schlüter E Grindelallee Bundesstrasse Staats- u. Universitäts- strasse Bibliothek Curio-Haus Feldbrunnenstrasse Hamburg D An der Verbindungsbahn Moorweidenstrasse Rothenbaumchaussee Flügel West D Uni-Haupt- Tier gebäude g art C e n s trasse Edmund-Siemers-Allee B Tesdorpfstr. PLANTEN UN BLOMEN MOOR- WEIDE Congress Parksee Centrum Flügel Hamburg A Ost Theodor- Heuss- A grey: Congress Center / CCH Platz B dark-brown: East Wing Building C turquoise: Main Building DAMMTOR D yellow: West Wing Building E mint: Economical Building F white: Campus MensaStraße G green: Social ScienceMarseiller Building STEPHANS- PLATZ H orange:Eingang Educational Building I blue:O st PhilosophicalBucerius Tower J red: AuditoriumJungiu LawSchool Maximum Alter Botanischer Kfenpurple: Law Building Teich Dammtordamm str Garten L pink: Main Mensa E Content Content Welcome to ICME-13 5 Committees of ICME-13 6 Congress Information / Overview 7 General Information 8 Opening and Closing Ceremony 14 Lectures of the ICMI awardees 15 Plenary Activities 16 Invited Lectures 20 ICMI Studies and Survey Teams 26 ICMI Affiliate Organisations 30 National Presentations 34 Thematic Afternoon 36 Topic Study Groups 44 Oral Communications 146 Poster 258 Discussion Groups 308 Workshops 326 Mathematical Exhibition 344 Early Career Researcher Day 345 Teachers’ Activities 348 For your notes 350 Sponsors and Supporters 355 Page 4 13th International Congress on Mathematical Education (ICME-13) · 24 – 31 July 2016 in Hamburg Welcome Welcome to ICME-13 The Society of Didactics of Mathematics (Gesellschaft für Didaktik der Mathematik – GDM) has the pleasure of hosting ICME-13 in 2016 in Germany. -

The Future of the University.Qxd

Maria Kelo (ed.) Maria Kelo (ed.) The Future of the University Translating Lisbon into Practice Today, Europe is a wealthy continent. But tomorrow, it could be much poorer. An unfavourable demographic development, the high price of labour, and relentless competition from old and new competitors threaten Europe’s comfortable position. To counterbalance these dangers, Europe has adopted the Lisbon Strategy. It sets Europe the aim of becoming a world leader in innovation and knowledge creation. Alongside with further knowledge producers, universities and other higher edu- cation institutions have a key role in making the Lisbon Strategy work. However, in their present state, Europe’s universities are ill-equipped to become innovation engines. In order to play this role, they themselves need to change. They need more funds than they have today, they need better governance structures, and they must enhance their global appeal. These issues – governance, funding and international attractiveness of Europe’s universities – are key concerns of this book. The volume ACA Papers on also depicts the main outlines of the Lisbon Strategy. Lemmens Most of the contributions in this volume are based on The Future of the University International Cooperation in Education presentations delivered at the ACA conference The future of the university, held in Vienna in December 2005. ISBN 3-932306-78-3 Maria Kelo (ed.) THE FUTURE OF THE UNIVERSITY Translating Lisbon into Practice ACA Papers on International Cooperation in Education Maria Kelo (ed.) THE FUTURE -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Mathematics In

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 56/2014 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2014/56 Mathematics in Undergraduate Study Programs: Challenges for Research and for the Dialogue between Mathematics and Didactics of Mathematics Organised by Rolf Biehler, Paderborn Reinhard Hochmuth, Hannover Dame Celia Hoyles, London Patrick W. Thompson, Tempe 7 December – 13 December 2014 Abstract. The topic of undergraduate mathematics is of considerable con- cern for mathematicians in universities, but also for those teaching mathemat- ics as part of undergraduate studies other than mathematics, for employers seeking to employ a mathematically skilled workforce, and for teacher edu- cation. Different countries have made and continue to make massive efforts to improve the quality of mathematics education across all age ranges, with most of the research undertaken particularly at the school level. A growing number of mathematicians and mathematics educators now see the need for undertaking interdisciplinary research and collaborative reflections around issues at the tertiary level. The conference aimed to share research results and experiences as a background to establishing a scientific community of mathematicians and mathematics educators whose concern is the theoreti- cal reflection, the research-based empirical investigation, and the exchange of best-practice examples of mathematics education at the tertiary level. The focus of the conference was mathematics education for mathematics, engi- neering and economy majors and for future mathematics teachers. -

How Affect-Aware Feedback Can Improve Student Learning

Affecting Off-Task Behaviour: How Affect-aware Feedback Can Improve Student Learning Beate Grawemeyer Manolis Mavrikis Wayne Holmes London Knowledge Lab London Knowledge Lab London Knowledge Lab Birkbeck, University of London UCL Institute of Education UCL Institute of Education London, UK University College London, UK University College London, UK [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Sergio Gutierrez-Santos Michael Wiedmann Nikol Rummel London Knowledge Lab Institute of Educational Institute of Educational Birkbeck, University of London Research Research London, UK Ruhr-Universität Bochum, DE Ruhr-Universität Bochum, DE [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords This paper describes the development and evaluation of an Affect, Feedback, Exploratory Learning Environments affect-aware intelligent support component that is part of a learning environment known as iTalk2Learn. The intelligent support component is able to tailor feedback according to a 1. INTRODUCTION student’s affective state, which is deduced both from speech The aim of our research is to provide intelligent support to and interaction. The affect prediction is used to determine students, taking into account their affective states in order which type of feedback is provided and how that feedback to enhance their learning experience and performance. is presented (interruptive or non-interruptive). The system It is well understood that affect interacts with and in- includes two Bayesian networks that were trained with data fluences the learning process [19, 10, 3]. While positive gathered in a series of ecologically-valid Wizard-of-Oz stud- affective states (such as surprise, satisfaction or curiosity) ies, where the effect of the type of feedback and the presen- contribute towards learning, negative ones (including frus- tation of feedback on students’ affective states was investi- tration or disillusionment at realising misconceptions) can gated. -

SRHE News Issue 11 – February 2013

SRHE News Issue 11 – February 2013 Editorial Annual Conference: What is Higher Education for? Rob Cuthbert The 2012 Annual Research Conference was possibly the best ever, with 220 research papers, 9 symposia, and - that rarity in any conference - five well- received plenary presentations. The opening address from Howard Hotson (Oxford), Chair of the newly-formed Council for the Defence of British Universities, established a suitably global perspective, implicating multinational business in his reinterpretation of the ‘global university crisis’. Georg Krucken (Kassel) offered a different, classically European, interpretation of ‘contemporary transformations’, and Suellen Shay (Cape Town) provided a third intellectually challenging and concept-packed analysis of change, focusing on the curriculum. SRHE’s outgoing President David Watson supplied a typically well-organised and elegant analysis of HE’s claims to transformation, and Vice-President Roger Brown was in his usual challenging and compelling form on politics and policymaking in HE. These splendid plenaries punctuated the ever-richer mix of research papers from some 350 participants from more than 35 countries. Whether your interests were in academic practice, the student experience, HE policy, learning and teaching or leadership, management and quality, there were in every session difficult choices between competing papers promising new ideas and new evidence. The Conference is now a well-established landmark in the higher education year, with good media coverage, especially in the Times Higher Education, which this year featured SRHE International Network convener Linda Evans’ (Leeds) research on the role of the professor, as reported in THE on 20 December 2012. The conference content also reflected the fast-changing media landscape, with a growing number of papers addressing the uses and implications of mobile technologies, websites, blogs and social media for HE and its future purposes. -

Learning Progression in Secondary Students' Digital Video Production

Learning progression in secondary students' digital video production Stephen Connolly London Knowledge Lab, Institute of Education, University of London This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 I hereby declare that, except where explicit attribution is made, the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. 86,000 words (rounding to the nearest thousand and excluding bibliography, references and appendices) ABSTRACT OF THESIS Assessing learning progression in Media Education is an area of study which has been largely neglected in the history of the subject, with very few longitudinal studies of how children learn to become "media literate" over an extended period of time. This thesis is an analysis of data over three years (constituted by the production of digital video work by a small group of secondary school students) which attempts to offer a more extended account of this learning. The thesis views the data through three concepts (or "lenses") which have been key to the development of media education in the UK and abroad. These are Culture, Criticality and Creativity, and the theoretical perspectives that the thesis should be viewed in the light of include the work of Bourdieu, Vygotsky, Heidegger and Hegel. The examination of the student production work carried out in the light of these three lenses suggests that learning progression comes about because of a relationship between all three, the key metaphorical idea put forward by the thesis that describes that relationship is the dialectic of familiarity. This suggests that for media education at least, the learning process is a dialectic one, in which students move from cultural and critical knowledge and experiences that are familiar -or thetic - to ones that are unfamiliar, and hence antithetical.