GRAND MANAN ISLAND PERCEPTIONS of ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS and CHANGE by Danielle M. Cadieux a Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My New Brunswick — GRAND MANAN Island

My ew runswick GRAND MANAN Island Grand Manan’s famous Swallowtail lighthouse. Story and photos by Larry Dickinson and Steve Rogers n a small island in the Bay of Fundy When you arrive on the ferry, you pass watching or sunset cruise. Olies a mystical place called Grand the iconic Swallowtail Lighthouse that Beaches on Grand Manan come in all Manan. It is a place of legends and lore, stands guard over the island and has done so sizes and shapes. The texture of the beaches and it’s only a 90-minute ferry ride from for 160 years. It is one of New Brunswick’s also changes. Many seem to endlessly the mainland. most photographed lighthouses and even stretch along the bays, coves and harbours The island is very peaceful and appears on a Canadian stamp. of the island. Seal Cove, Deep Harbour, relaxing, with its stunning scenery and Grand Manan is on the eastern fyway and the Anchorage are popular with natural resources. It has become a laid- for migratory birds. More than 400 species locals and visitors alike. You can spend a back paradise for kayakers, hikers and have been counted on the island. Every relaxing afternoon lying on the sand in the bird-watchers. The salt air and summer September, bird watchers travel to the warm sun and listening to the waves. Or sun seems to make everyday problems island and head to the marshes to see fnd treasures such as beach glass, pottery disappear. hundreds of bird species. shards, driftwood, shells and sand dollars The island’s rocky, cliff-lined coast, Puffns are a must-see during your visit. -

Geology of the Island of Grand Manan, New Brunswick: Precambrian to Early Cambrian and Triassic Formations

GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA / MINERALOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA JOINT ANNUAL MEETING 2014 UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK, FREDERICTON, NEW BRUNSWICK, CANADA FIELD TRIP B3 GEOLOGY OF THE ISLAND OF GRAND MANAN, NEW BRUNSWICK: PRECAMBRIAN TO EARLY CAMBRIAN AND TRIASSIC FORMATIONS MAY 23–25, 2014 J. Gregory McHone 1 and Leslie R. Fyff e 2 1 9 Dexter Lane, Grand Manan, New Brunswick, E5G 3A6 2 Geological Surveys Branch, New Brunswick Department of Energy and Mines, PO Box 6000, Fredericton, New Brunswick, E3B 5H1 i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables..............................................................................................................i Safety............................................................................................................................................ 1 Itinerary ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Part 1: Geology of the Island of Grand Manan......................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Precambrian Terranes of Southern New Brunswick ..................................................................... 3 Caledonia Terrane ............................................................................................................. 7 Brookville Terrane ............................................................................................................ -

MCP No 02-E.Cdr

Silica Natural Resources Lands, Minerals and Petroleum Division Mineral Commodity Profile No. 2 ilicon (Si) is the second most common element on Earth after World Production and Reserves Soxygen. Si does not occur naturally in its pure state but instead is found chiefly in mineral form as either silica (SiO2) or silicates. Silica Silica deposits occur, and are mined, in most and/or silicate minerals are a constituent of nearly every rock type in countries. Global silica output is estimated at Earth's crust. roughly 120 Mt to 150 Mt per year (Dumont 2006). The most familiar silica mineral is quartz. In commodity terms, silica About 5.9 Mt of ferrosilicon were produced also refers to geological deposits enriched in quartz and/or other silica worldwide in 2006. The major contributors were minerals. Silica resources include 1) poorly consolidated quartzose China, Russia, United States, Brazil and South sand and gravel, 2) quartz sand/pebbles in consolidated rock (e.g. Africa (U.S. Geological Survey [USGS] 2006). quartzose sandstone), 3) quartzite , and 4) quartz veins. Global production of silicon metal reportedly Uses approached 1.2 Mt in 2006, almost half of which came from China (USGS 2006). Other important Silica is hard, chemically inert, has a high melting point, and functions producers are the United States, Brazil, Norway, as a semiconductor—characteristics that give it many industrial France, Russia, South Africa and Australia. applications. Silica deposits generally must be processed to remove iron, clay and other impurities. The most valuable resources contain Silica Consumption in Canada (Total = 2.57 Mt) >98% SiO2 and can be readily crushed into different sizes for the various end products. -

Hon. J.W. Pickersgill MG 32, B 34

Manuscript Division des Division manuscrits Hon. J.W. Pickersgill MG 32, B 34 Finding Aid No. 1627 / Instrument de recherche no 1627 Prepared in 1991 by Geoff Ott and revised in Archives Section 2001 by Muguette Brady of the Political -ii- Préparé en 1991 par Geoff Ott et révisé en 2001 par Muguette Brady de la Section des Archives politiques TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PRE-PARLIAMENTARY SERIES ............................................... 1 SECRETARY OF STATE SERIES, 1953-1954 ..................................... 3 CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION SERIES ..................................... 4 Outgoing Correspondence - Sub-Series ........................................ 4 Citizenship - Sub-Series .................................................... 5 Estimates - Sub-Series .................................................... 28 National Gallery - Sub-Series .............................................. 32 National Film Board - Sub-Series ........................................... 37 Indian Affairs Branch - Sub-Series - Indian Act ................................. 44 Indian Affairs Branch - Sub-Series - General ................................... 46 Immigration - Sub-Series .................................................. 76 Immigration Newfoundland - Sub-Series ..................................... 256 Immigration - Miscellaneous - Sub-Series .................................... 260 Public Archives of Canada - Sub-Series ...................................... 260 National Library of Canada - Sub-Series .................................... -

Triassic Basin Stratigraphy at Grand Manan, New Brunswick, Canada J

Document generated on 09/27/2021 4:33 p.m. Atlantic Geology Triassic Basin Stratigraphy at Grand Manan, New Brunswick, Canada J. Gregory. McHone Volume 47, 2011 Article abstract The island of Grand Manan (Canada) in the southwestern Bay of Fundy has the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/ageo47art06 only exposed strata and basalt of the Grand Manan Basin, a mainly submerged Early Mesozoic riſt basin about 30 km wide by 70 km long. The basin is See table of contents bounded on the southeast by the west-dipping Red Point Fault, which bisects the island, and on the northwest by a submarine border fault marked by the Murr Escarpment, a bathymetric feature that parallels the coast of Maine Publisher(s) (USA). A fault-bounded horst of Ediacaran to Cambrian rocks separates the Grand Manan Basin from the much larger Fundy Basin to the east. The Atlantic Geoscience Society Ashburton Head, Seven Days Work, and Southwest Head members of the end-Triassic Dark Harbour Basalt cover most of western Grand Manan with a ISSN total thickness around 240 m. Up to 12 m of sub-horizontal grey mudstone and fine-grained red sandstone of the Dwellys Cove Formation are exposed along 0843-5561 (print) the western shoreline beneath the basalt. Coarse red arkosic sandstone a few 1718-7885 (digital) metres thick at Miller Pond Road rests on a basement of Late Ediacaran rocks east of the basin. Exposures of the Dwellys Cove and Miller Pond Road Explore this journal formations are at the top and bottom, respectively, of several km (?) of sub-horizontal Late Triassic clastic basin strata, juxtaposed by the eastern border fault. -

The British American Navigator, Or, Sailing Directory for the Island And

Tin-: >"» -I BRITISH AMERICAN NAVIGATOR; -V, - OH SAILING DIRECTORY FOR THE ISLAND AND BANKS OF NEWFOUNDLAND, THE GULF AND RIVER OF ST. LAWRENCE, Breton Ssilanlr, M NOVA SCOTIA, THE RAY OF FUNDY, AND THE COASTS THENCE TO THE RIVEll PENOBSCOT, &c. ^ I i i i OniOINALLY COMPOSED By JOHN PURDY, Hydrographer; AND COMPLETED, FROM A GREAT • VARIETY OV DOCUMENTS, PUHUC AND PRIVATE, By ALEX. G. FINDLAY. ^ A LONDON: PRINTED FOR R. H. LAURIE, CHAKT-SELLER TO THE ADMIRALTY, THE HON. CORPORATION OF TRINITY-HOUSE, kc i! No. 53, FLEET STREET. 1843. i>_ " •'*•.'?•>. : ->'t ^\^jr' ;:iii2£aa£; .i.":. rriar- r._. — 187056 y ADVERTISEMENT. The following Charts will be found particularly adapted to this Work, and are distinguished by the seal, as in the title-page : 1. A GENERAL CHART of the ATLANTIC OCEAN, according to the Observa- lions, Surveys, and Determinations, of the most eminent Navigators, British and Foreign; from a Combination of which the whole has been deduced, by John Purdy. With parti- cular Plans of the Roadstead of Angra, Terceira, Ponta-Delgada, St. Michael's, of the Channel between Fayal and Pico, Santa-Cruz to Funchal, &c. On four large sheets. tit With additions to the present time. \6s. sen ',• The new Chart of the Atlantic may be had in two parts, one containing the northern and the other the southern sheets ; being a form extremely convenient for use at sea. 2. The ATLANTIC, or WESTERN OCEAN, with Hudson's Bay and other adjacent Seas ; including the Coasts of Europe, Africa, and America, from sixty-five degrees of North Latitude to the Equator ; but without the particular Plans above mentioned. -

Lights and Shadows of Eighty Years : an Autobiography

-w^ D\OZ>'D VJfjj^o , j7C-//»^ eANAOfANA OHPARTft^Nr MORTH VOfiK PU81.JC UBRAW' REV. JOSHUA N. BARNES. LIGHTS AND SHADOWS OF EIGHTY YEARS AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY BY Rev. Joshua N. Barnes. Revised and Edited by His Son, EDWIN N. C. BARNES. Author of 'The Reconciliation of Randall Claymore," "King Sol in Flowerland," etc. WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY REV. JOSEPH McLEOD, D. D., Editor of The Maritime Baptist, Vice-President for Canada of The World's Baptist Alliance. PRICE, $1.35. ST. JOHN, N. B. Printed by Barnes & Company, Ltd. 1911. Copyright, in Canada, 1911. BY EDWIN N. C. BARNES. REV. B. H. NOBLES. Pastor Victoria Street United Baptist Chinch, St. John. INTRODUCTION. This little book tells the life story of a good man. It makes no pretension to literary finish. It is purely a record, simply phrased, of more than fifty years in the Christian ministry. The writer has been known through all these years as a man of real humbleness, great faith, deep devotion and tireless activity in the work of the Lord. His work has been abundantly blessed. The results of his consecrated service are not alone in the large number won to the faith of Jesus, in churches established, and in the care of the flock of God, but in the number of young men converted under his ministry, who became preachers of the gospel and successful winners of souls. Rarely has a minister a more striking record in this respect. The story furnishes some knowledge of religious conditions in earlier years in New Brunswick, and of the diflficulties which confronted the servants of God. -

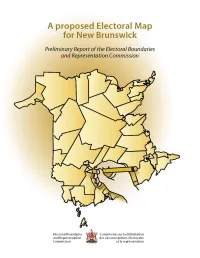

A Proposed Electoral Map for New Brunswick Preliminary Report of the Electoral Boundaries and Representation Commission

A proposed Electoral Map for New Brunswick Preliminary Report of the Electoral Boundaries and Representation Commission Electoral Boundaries Commission sur la délimitation and Representation des circonscriptions électorales Commission et la représentation Preliminary Report of the Electoral Boundaries and Representation Commission November 2005 2 Preliminary Report of the Electoral Boundaries and Representation Commission 3 Preliminary Report of the Electoral Boundaries and Representation Commission 4 Preliminary Report of the Electoral Boundaries and Representation Commission Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Historical Overview .......................................................................................................................................... 1 The Electoral Boundaries and Representation Act ................................................................................................. 6 Public Input ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 Regional Approach ............................................................................................................................................ 13 Central New Brunswick ................................................................................................................................... 14 -

Rapport Annuel 2009-2010 Annual Report

2009-2010 2009-2010 Annual Report Rapport annuel Department of Ministère du Wellness, Culture Mieux-être, and Sport de la Culture et du Sport 2009-2010 2009-2010 Annual Report Rapport annuel Department of Ministère Wellness, Culture du Mieux-être, and Sport de la Culture et du Sport 2009-2010 Annual Report Rapport annuel 2009-2010 Published by: Publié par : Department of Wellness Culture and Sport Ministère du Mieux-être, de la Culture et du Sport Province of New Brunswick Province du Nouveau-Brunswick P. O. Box 6000 Case postale 6000 Fredericton, New Brunswick Fredericton (Nouveau-Brunswick) E3B 5H1 E3B 5H1 Canada Canada http://www.gnb.ca http://www.gnb.ca December 2010 Décembre 2010 Cover: Couverture : Communications New Brunswick Communications Nouveau-Brunswick Printing and Binding: Imprimerie et reliure : Printing Services, Supply and Services Services d‟imprimerie, Approvisionnement et Services ISBN xxx-x-xxxxx-xxx-x ISBN xxx-x-xxxxx-xxx-x ISSN xxxx-xxxx ISSN xxxx-xxxx Printed in New Brunswick Imprimé au Nouveau-Brunswick The Honourable Graydon Nicholas L‟honorable Graydon Nicholas Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of New Lieutenant-gouverneur du Brunswick Nouveau-Brunswick May it please your Honour: Votre Honneur, It is my privilege to submit the Annual Je suis heureux de vous soumettre le Report of the Department of Wellness, rapport annuel du ministère du Mieux- Culture and Sport, Province of New être, de la Culture et du Sport du Brunswick, for the fiscal year April 1, 2009, Nouveau-Brunswick pour l‟exercice to March 31, 2010. financier allant du 1er avril 2009 au 31 mars 2010. -

~Nalla~R~C (CANADA a GEOLOGY FIELD "GUIDE to SELECTED SITES in NEWFOUNDLAND, NOVA SCOTIA

D~s)COVER~NGROCK~~ ~j!NERAl~ ~NfO)FOs)S~l5) ~NAllA~r~C (CANADA A GEOLOGY FIELD "GUIDE TO SELECTED SITES IN NEWFOUNDLAND, NOVA SCOTIA, PRINCE EDV\JARDISLAND7 AND NEW BRUNSWICK 7_".-- ~ _. ...._ .•-- ~.- Peter Wallace. Editor Atlantic Geoscience Society Department of Earth Sciences La Societe G60scientifique Dalhousie University de L'Atlantique Halifax, Nova Scotia AGS Special Publication 14 • DISCOVERING ROCKS, MINERALS AND FOSSILS IN ATLANTIC CANADA A Geology Field Guide to Selected Sites in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick • Peter Wallace, editor Department of Earth Sciences Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia Atlantic Geoscience Society La Societe Geoscientifique de L'Atlantique • AGS Special Publication • @ 1998 Atlantic Geoscience Society Department of Earth Sciences Dalhousie University 1236 Henry Street, Halifax Nova Scotia, Canada B3H3J5 This book was produced with help from The Canadian Geological Foundation, The Department of Earth Sciences, Dalhousie University, and The Atlantic Geoscience Society. ISBN 0-9696009-9-2 AGS Special Publication Number . 14.. I invite you to join the Atlantic Geoscience Society, write clo The Department of Earth Sciences, Dalhousie University (see above) Cover Photo Cape Split looking west into the Minas Channel, Nova Scotia. The split is caused by erosion along North-South faults cutting the Triassic-Jurassic-aged North Mountain Basalt and is the terminal point of a favoured hike of geologists and non-geologists alike. Photo courtesy of Rob • Fensome, Biostratigrapher, -

Grand Manan Channel ! Baie Long Island Bay

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A B C D E ! F G H I J ! ! ! ! ! ! POINTE LONGS EDDY POINT ° ! NORTHERN HEAD THE BISHOP ! ! ! ASHBURTON HEAD ! ! ! EL E BR 1 ! E330 O OK 1 ! ! U A E ! S ! IS U DUMP R ! INDIAN ! BEACH ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! LAC EEL LAKE ! ! LAC ! FISH HEAD ! LITTLE ROCKY CORNER LAKE ! ! HOLE IN THE WALL ANSE MONEYS COVE ! ! PRIVATE F E R ! ! AIR R Y STRIP p C R E O ! ! L ANSE S S T I WHALE N S G I R ! COVE ! U H I ! S W W S ! E MONEY H NORTH HEAD A U A L E DEXTERS ! C B ! O E RO C DURANT V OK Y M O MOSES R R V E ! T A FERN ! E E F TATONS CORNER Y N M E X O L E O H L ! N C P I ! G F T H GROVE O T A E 776 A H OUS T ,+ O ' R ANSE SAWPIT COVE D S A S776 ! L ! M WHALE E SWALLOW TAIL M L.H. MILLER cKAY COVE EXT. PETTES ° F410 1 !( COVE ! ! STANLE BR S777 Y P415 ANSE O O ANSE PETTES K ! 2 R 2 U ! FLAGG ! COVE I GR 2 !¿ OLD AIRPORT S EEN !( COVE S ! E ! AU E V N465 POINTE O ! C ! NET POINT K ! HS O MIT L O A ! R ETANG S E B ! OHIO S OLD AIRPORT EXT. ETANG ! POND ! WILSON ! ! POND 3 D460 ! !( ! D R N ! K ! U ETANG RICH POND A RU C ! I R I O S S D G S S EAU E ! A U K U A O E O D D ISS O R ! ° A RU C B R K K ! H PORT ! A DARK R HARBOUR B O ! UR CANAL GRAND MANAN CHANNEL ! BAIE LONG ISLAND BAY ! BR O O K ! ! D055 K ANSE ! C HERRING O COVE D ! RU ! IS S AR EAU ED LAURIE C MARSH ! ETANG M DAVID WATT IL CASTALIA ! M392 L POND K HAR ! MARSH DAR BO UR OK 3 BRO 3 ! M127 ÎLE M388 LONG M382 ! ISLAND D055 HILL ! N ! ETO DL MID ) ETANG (PR G ROUND ! IN B618 D GREAT MARSH POND LAN MARS H ! B ANCRO FT ! F430 ! POINTE S S BANCROFT POINT GRAND E C VALLEY C ! OINT A T P T R OF R BANC ETANG O LITTLE P ! IR ROUND A POND W E ! N ! ÎLE HIGH DUCK ISLAND ! PORT TEMPLE BAY OF FUNDY LITTLE DARK HILL ÎLE LOW DUCK ISLAND ! ( POINTE HARBOUR m RAGGED POINT BAY OF FUNDY BAIE DE FUNDY ! W.C. -

History Islands and Isletes in the Bay of Fundy

V r iiis'ronv OF IN THE BAY OF XI) Y, Charlotte County, New Bmuswick: HjOM THE IE EARLIEST SETTLEMENT TO THE t>KEbf.NT time; ixoLimixo Sketches of Shipwrecks and Other Events of Exciting Interest BY J. G. LOEIMER, Esq f>N. B. 'iUX I EU AT THE OFFICE OF THE SAINT CKOIX COURIEE 1<S76 » — t- I CONTESTS. CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTORY. The Bay- Its Peculiarities—Rivers—Capes—Cape Blomidon—Basin of Minas—Tides—Fogs—Bay de Verte —Wellington Dyke—Counties Washed, &c. Page 5. CHAPTER II. GRAND MANAN, Early History— Seal Cove—Outer Islands—Grand Harbour—Wood- ward's Cove—White Head—Centrevilie —North Head—Eel Brook Long Island—Other Islets—Shipwrecks—Minerals, <§&. Page 11. CHAPTER III. MACHIAS SEAL ISLAND. Description—The Connollys—Lights—Shipwrecks—Fish and Fowl, &c. Page 71. CHAPTER IV. INDIAN ISLAND Early History—James Ohaflfey—Indian Belies—Le Fontaine—Smug- gling—Fight for Tar-^Capture of Schooner—John Doyle's Song —Fenians and the British Flag—Stores Burnt—Island Fleet—Customs —Indians' Burying Ground, &c. Page 73. CHAPTER V. DEER ISLAND. Early History—Peculiarity of Road System—Fish less Lake—Indian Relics—Coves—Churches—Schools — Temperaace—Whirlpools—Loss . — 4 Contents. of Life—Boat swallowed up in Whirlpools— Pious Singing Saves a Boatman—Lobster Factory, &c. Page 89. CHAPTER VL C AMPOBELLO Early History— Surveying Steamer Columbia—Minerals— Harbours Lighthouse—Churches— Schools— VVelchpool —Wilson's Beach—Admi- £ ral Owen — Captain Robinson-Owen— 'ish Fairs—Boat Racing—Vete- ran Mail Carrier—Central Road-— Harbour de Lute, &c. Page 97. CHAPTER VIL RECAPITULATORY AND CONCLUSIVE, Remarks -The Bay— The " Bore "—Lives Lost —Five Lights—Salt- Water Triangle—Militia Training - G teat Hole Through a Cliff— Wash- ington and Wellington—Minerals— Beautiful Specimens—New Weir —Porpoise Shooting—Fertility—Houses and Stores —Pedlars—Post- Offices—Mail-Vessels—Schooneis—Boats and Steamer—Singular Fruit —General Review—Closing Remarks.