Commerce Act 1986: Business Acquisition Section 66: Notice Seeking Clearance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inbound E-Directory 2016

INBOUND E-DIRECTORY 2016 What is the Tourism Export Council of New Zealand? The Tourism Export Council of New Zealand is a trade association that has represented the interests of inbound tourism since 1971. Their inbound members package holidays for international visitors whether they be part of a group tour, independent traveller, conference/incentives, education or cruise visitors. What do we do & who do we represent? The Tourism Export Council’s focus is to build long term business relationships with distribution networks in New Zealand and offshore. The relationship with product suppliers in New Zealand and offshore wholesalers is integral to the country’s continued growth as a visitor destination. Member categories include: . Inbound member - inbound tour operators (ITO’s) . Allied member - attraction, activity, accommodation, transport and tourism service suppliers Examples of the allied membership include: . Attraction – Milford Sound, SkyTower, Te Papa Museum . Activities – Jetboating, Whalewatch, Maori Culture show . Accommodation – hotels, luxury lodges, backpackers . Transport – airlines, bus & coaches, sea transport, shuttles . Tourism services – Regional Tourism Organisations (RTO’s) digital & marketing companies, education & tourism agencies eg. DOC, Service IQ, Qualmark, AA Tourism, BTM Marketing, ReserveGroup Why is tourism considered an export industry? Tourism, like agriculture is one of New Zealand’s biggest income earners. Both are export industries because they bring in foreign dollars to New Zealand. With agriculture, you grow an apple, send it offshore and a foreigner eats it. A clear pathway of a New Zealand product consumed or purchased by someone overseas. Tourism works slightly differently: The product is still developed in NZ (just like the apple) It is sold offshore (like the apple) It is purchased by a foreigner (again like the apple) BUT it is experienced in NZ and therein lies the difference. -

Draft Proposed Submission

Wealden District Council Local Plan Wealden Local Plan Draft Proposed Submission 14th March 2017 How to Contact Us Planning Policy Wealden District Council Council Offices, Vicarage Lane, Hailsham, East Sussex BN27 2AX Telephone 01892 602007 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.wealden.gov.uk Office hours Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday 8.30am to 5.00pm and Wednesday 9.00am to 5.00pm You may also visit the offices Monday to Friday, to view other Local Plan documents. A copy of the Wealden Local Plan and associated documents can be downloaded from the Planning Policy pages of the Wealden website, www.wealden.gov.uk/planningpolicy or scan the QR code below with your smart phone. If you, or somebody you know, would like the information contained in this document in large print, Braille, audio tape/CD or in another language please contact Wealden District Council on 01323 443322 or [email protected] Wealden Local Plan Draft Proposed Submission - 14th March 2017 1 Introduction 13 Evidence and Conformity 13 Local Plan Process 14 Superseded Plans 14 Neighbourhood Plans 15 The Structure of the Plan 15 Contents 2 Representations 17 3 Context 21 Geography and Settlement Pattern 21 The Environment 23 The Economy 25 Health and Wellbeing 26 Connectivity 27 Settlement Hierarchy 27 4 Vision and Spatial Objectives 31 5 Ashdown Forest SAC 37 Habitat Regulations 37 Ashdown Forest SAC Habitats 37 Impact of Growth on Ashdown Forest SAC 37 Compensatory measures 40 Ashdown Forest Policy 40 6 Strategic Growth Policies 41 Provision of Homes and Jobs 41 -

Individual Submissions J - Z Contents Page

Individual Submissions J - Z Contents Page Please note: As some submitters did not provide their first names they have been ordered in the submissions received list under their title. These submitters are as follows: o Mr Burgess is ordered in the submissions received list under ‗M‘ for Mr o Mrs Davey is ordered in the submissions received list under ‗M‘ for Mrs o Mrs Dromgool is ordered in the submissions received list under ‗M‘ for Mrs o Mrs Peters is ordered in the submissions received list under ‗M‘ for Mrs o Mr Ripley is ordered in the submissions received list under ‗M‘ for Mr We apologise for any confusion the above ordering of submissions may have caused. If your submission is not displayed here, contains incorrect information or is missing some parts, please email us on [email protected] or contact Mathew Stewart on (09) 447 4831 Sub # Submitter Page 851 J Dromgool 13 870 Jacob Phillips 13 15 Jacob Samuel 13 178 Jacqueline Anne Church 13 685 Jacqui Fisher 13 100 James Houston 13 854 James Lockhart 13 302 Jamie Revell 13 361 Jan Heijs 14 372 Jane Blow 14 309 Jane Briant-Turner 14 482 Janet Hunter 14 662 Janet Pates 14 656 Janie Flavell 14 634 Jarrod Ford (NB: we apologise if this name is incorrect, we were 14 unable to clearly decipher the writing) 718 Jason Lafaele 14 605 Jaydene Haku 15 746 Jeanette Collie 15 149 Jeanette Valerie Cooper 15 177 Jennifer Collett 15 681 Jennifer Olson 15 818 Jennifer Preston 15 832 Jenny TeWake 15 1 Sub # Submitter Page 373 Jeremy Lees-Green 15 85 Jesse McKenzie 16 843 Jessica Currie -

AT Deliverables Project Results to 31 March 2020

AT Deliverables Project Results to 31 March 2020 FINANCE Task / Project Strategic Theme Project Results Comment/s Finance Review completed. Findings will be incorporated into the Reshape AT Review of current billing process for non-core external revenues On Target project. The overall structure of the Performance Management Framework is Version 1.0 of organisational Performance Management Framework created On Target completed, and the overarching level 1 metrics are confirmed. 2019/20 Half Year Audit and Reporting Continually transform and elevate customer On Target experience AC Quarter 2 reporting pack submitted On Target 2020/21 Budget (Annual Plan) prepared, with key focus on PT growth, special Pre Covid budget approved, submitted to AC as planned. Covid-19 budget On Target events, capital delivery and funding submitted to support consultation. Initiate work to asses funding options for electric buses Risk of non-achievement Work suspended due to Covid-19. Capital Performance Ensure forecasting and review processes are in place to deliver of 90% of the Risk of non-achievement Non achievement due to impacts of Covid-19. 2019-20 capital programme High level capital programme developed pre-Covid-19. Due to Covid-19 Contributes towards achievement of all 2020-21 high level Capital programme finalised Below, but likely to achieve impacts AT’s 2020/21 capital envelope will be materially reduced and will Strategic themes be finalised between now and 31 July. Working closely with ATAP and LTP working groups to ensure there is Contribute to the development of the 2021-2031 RLTP On Target alignment between the new plans and the current operating environment. -

Comfortdelgro Corporation Limited Annual Report 2008

ComfortDelGro Corporation Limited Annual Report 2008 Driven Our Vision To be the undisputed global leader in land transport. Contents 1 Our Mission 2 Key Messages 6 Global Footprint 8 Chairman’s Statement 12 Group Financial Highlights 14 Board of Directors 18 Key Management 24 Green Statement 26 Operations Review 47 Corporate Governance 53 Directories 57 Financial Statements 57 Report of the Directors 63 Independent Auditors’ Report 64 Balance Sheets 66 Consolidated Profi t and Loss Statement 67 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 68 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 70 Notes to the Financial Statements 138 Statement of Directors 139 Share Price Movement Chart 140 Shareholding Statistics 141 Notice of Annual General Meeting Proxy Form Corporate Information Globally we are No.2 with a presence in 7 countries, 26 cities, and a total fl eet of 45,000 vehicles. 33,600 taxis 7, 8 0 0 buses 41 km of rail track Our Mission To be the world’s number one land transport operator in terms of fl eet size, profi tability and growth. Five-Year Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) +8.9% +8.4% Group Turnover Net Profi t was S$3.1 billion in 2008, was S$200.1 million in 2008, up from S$2.0 billion in 2003 up from S$133.9 million in 2003 +13.1% +1.7% Overseas Turnover EBITDA* was S$1.3 billion in 2008, was S$541.7 million in 2008, up from S$706.2 million in 2003 up from S$498.9 million in 2003 +5.8% +3.8% Group Operating Profi t Net Asset Value Per was S$278.0 million in 2008, Ordinary Share up from S$209.6 million in 2003 was 74.7 cents in 2008, up from 62.0 cents in 2003 +24.1% +18.5% Overseas Operating Profi t Total Shareholder was S$129.8 million in 2008, Return up from S$44.1 million in 2003 * Refers to earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation and amortisation 1 ComfortDelGro Corporation Limited Annual Report 2008 Our Mission We aim to be No.1 Nothing is impossible. -

Stagecoach Group Plc – Preliminary Results for the Year Ended 30 April 2007

10 Dunkeld Road T +44 (0) 1738 442111 Perth F +44 (0) 1738 643648 PH1 5TW Scotland stagecoachgroup.com 27 June 2007 Stagecoach Group plc – Preliminary results for the year ended 30 April 2007 Business highlights • Delivering excellent performance and value to shareholders o Continued growth in earnings per share+ - up 10.4% o Underlying revenue growth in all core divisions o Around £700m in value returned to shareholders in May/June 2007 o Dividend increased by 10.8% • Partnerships and innovation driving growth at UK Bus o Continued organic passenger growth – like-for-like volumes up 6.6% o Strong revenue growth– like-for-like revenue up 10.3% o Like-for-like operating profit up 26.9% o Strong marketing, competitive fares strategy and concessionary travel schemes underpin growth o Named UK Bus Operator of the Year • Excellent performance in UK Rail o Strong start to new South Western rail franchise o Revenue up 12.8% o Contract wins: East Midlands; Manchester Metrolink • Strong growth in North America o Operating margin up from 7.1% to 7.9%, excluding Megabus o Continued strong revenue growth in both scheduled services and leisure markets – constant currency like-for-like revenue up 9.1% o Expansion of budget inter-city coach service, megabus.com, in United States • Growth at Virgin Rail Group o Continued revenue growth on West Coast and CrossCountry franchises o Winning market share from airlines o Good prospects for re-negotiated West Coast franchise • Stagecoach Group Board appointment o Appointment of Garry Watts as non-executive -

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS (New Entries First with Older Entries Retained Underneath)

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS (new entries first with older entries retained underneath) Now go back to: Home Page Introduction or on to: The Best Timetables of the British Isles Summary of the use of the 24-hour clock Links Section English Counties Welsh Counties, Scottish Councils, Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland, Channel Islands and Isle of Man Bus Operators in the British Isles Rail Operators in the British Isles SEPTEMBER 25 2021 – FIRST RAIL RENEWS SPONSORSHIP I am pleased to announce that First Rail (www.firstgroupplc.com/about- firstgroup/uk-rail.aspx) has renewed its sponsorship of my National Rail Passenger Operators' map and the Rail section of this site, thereby covering GWR, Hull Trains, Lumo, SWR and TransPennine Express, as well as being a partner in the Avanti West Coast franchise. This coincides with the 50th edition of the map, published today with an October date to reflect the start of Lumo operations. I am very grateful for their support – not least in that First Bus (www.firstgroupplc.com/about- firstgroup/uk-bus.aspx) is already a sponsor of this website. JULY 01 2021 – THE FIRST 2021 WELSH AUTHORITY TIMETABLE Whilst a number of authorities in SW England have produced excellent summer timetable books – indeed some produced them throughout the pandemic – for a country that relies heavily on tourism Wales is doing an utterly pathetic job, with most of the areas that used to have good books simply saying they don’t expect to publish anything until the autumn or the winter – or, indeed that they have no idea when they’ll re-start (see the entries in Welsh Counties section). -

FINAL REPORT V1.0

FINAL REPORT v1.0 DfT - TRANSPORT DIRECT Project Support & Consultancy Services Framework FareXChange Scoping Study Project Reference - TDT / 129 June 2006 Prepared By: Prepared For: Carl Bro Group Ltd, Transport Direct Bracton House Department for Transport 34-36 High Holborn Zones 1/F18 - 1/F20 LONDON WC1V6AE Ashdown House 123 Victoria Street LONDON SW1E 6DE Tel: +44 (0)20 71901697 Fax: +44 (0)20 71901698 Email: [email protected] www.carlbro.com DfT Transport Direct FareXChange Scoping Study CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY __________________________________________________ 6 1 INTRODUCTION ___________________________________________________ 10 1.1 __ What is FareXChange? _____________________________________ 10 1.2 __ Background _______________________________________________ 10 1.3 __ Scoping Study Objectives ____________________________________ 11 1.4 __ Acknowledgments __________________________________________ 11 2 CONSULTATION AND RESEARCH ___________________________________ 12 2.1 __ Who we consulted _________________________________________ 12 2.2 __ How we consulted __________________________________________ 12 2.3 __ Overview of Results ________________________________________ 12 3 THE FARE SETTING PROCESS AND THE ROLES OF INTERESTED PARTIES _____________________________________________________________ 14 3.1 __ The Actors _______________________________________________ 14 3.2 __ Fare Stages and Fares Tables ________________________________ 16 3.3 __ Flat and Zonal Fares ________________________________________ 17 -

Multimodal Pricing and the Optimal Design of Bus Services: New Elements and Extensions

Multimodal Pricing and the Optimal Design of Bus Services: New Elements and Extensions Alejandro Andrés Tirachini Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Business School, University of Sydney, Australia July 2012 Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies The University of Sydney Business School The University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia Abstract This thesis analyses the pricing and design of urban transport systems; in particular the optimal design and efficient operation of bus services and the pricing of urban transport. Five main topics are addressed: (i) the influence of considering non-motorised travel alternatives (walking and cycling) in the estimation of optimal bus fares, (ii) the choice of a fare collection system and bus boarding policy, (iii) the influence of passengers’ crowding on bus operations and optimal supply levels, (iv) the optimal investment in road infrastructure for buses, which is attached to a target bus running speed and (v) the characterisation of bus congestion and its impact on bus operation and service design. Total cost minimisation and social welfare maximisation models are developed, which are complemented by the empirical estimation of bus travel times. As bus patronage increases, it is efficient to invest money in speeding up boarding and alighting times. Once on-board cash payment has been ruled out, allowing boarding at all doors is more important as a tool to reduce both users and operator costs than technological improvements on fare collection. The consideration of crowding externalities (in respect of both seating and standing) imposes a higher optimal bus fare, and consequently, a reduction of the optimal bus subsidy. -

State Transit Authority 2001 - 2002

State Transit Authority 2001 - 2002 Sydney Buses Sydney Ferries Newcastle Bus & Ferry Services annual reportannual annual reportannual www.sta.nsw.gov.au STATE TRANSIT AUTHORITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2001 - 2002 1 STATE TRANSIT AUTHORITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2001 - 2002 2 Table of Contents About State Transit 4 Performance Highlights 7 Year in Review 8 CEO’s and Chairman’s Foreword 9 Review of Operations 11 Reliability 12 Convenience 17 Safety and security 22 Efficiency 26 Courtesy - Customer Service 32 Comfort 38 Sydney Ferries Reform 41 Financial Statements 46 Appendices 81 Index 117 STATE TRANSIT AUTHORITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2001 - 2002 3 About State Transit - FAQ’s State Transit manages the largest bus and ferry operation in Australia. State Transit operates 4 businesses: Sydney Buses, Sydney Ferries, Newcastle Bus and Ferry Services and Western Sydney Buses (Liverpool-Parramatta Transitway). Bus Fleet · At year end, State Transit’s bus fleet totalled 1,935 buses: - 750 are air-conditioned (38.8% of fleet), - 579 are low floor design (30% of fleet), - 468 buses are fully wheelchair accessible (24.2% of fleet) - 368 buses are CNG powered (21% of the Sydney fleet) and - 360 buses have Euro 2 diesel engines (18.6% of the fleet). Ferry Fleet · 32 ferries operate services in Sydney Harbour and 2 ferries operate on Newcastle Harbour. · The ferry fleet consists of four Freshwater class vessels, three Lady class, eleven First Fleeters, three JetCats, seven RiverCats, two HarbourCats and four SuperCats. · Sydney Ferries operates across the length and breadth of Sydney Harbour and along the length of the Parramatta River into Parramatta. -

2020 Book News Welcome to Our 2020 Book News

2020 Book News Welcome to our 2020 Book News. It’s hard to believe another year has gone by already and what a challenging year it’s been on many fronts. We finally got the Hallmark book launched at Showbus. The Red & White volume is now out on final proof and we hope to have copies available in time for Santa to drop under your tree this Christmas. Sorry this has taken so long but there have been many hurdles to overcome and it’s been a much bigger project than we had anticipated. Several other long term projects that have been stuck behind Red & White are now close to release and you’ll see details of these on the next couple of pages. Whilst mentioning bigger projects and hurdles to overcome, thank you to everyone who has supported my latest charity fund raiser in aid of the Christie Hospital. The Walk for Life challenge saw me trekking across Greater Manchester to 11 cricket grounds, covering over 160 miles in all weathers, and has so far raised almost £6,000 for the Christie. You can read more about this by clicking on the Christie logo on the website or visiting my Just Giving page www.justgiving.com/fundraising/mark-senior-sue-at-60 Please note our new FREEPOST address is shown below, it’s just: FREEPOST MDS BOOK SALES You don’t need to add anything else, there’s no need for a street name or post code. In fact, if you do add something, it will delay the letter or could even mean we don’t get it. -

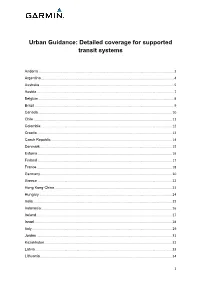

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia .................................................................................................................................................