Michael Sokolow on Boston Confronts Jim Crow, 1890-1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

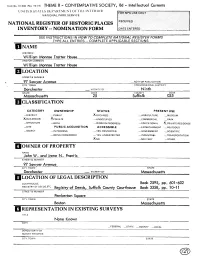

Nomination Form

Form NO. 10-300 (Rav. 10-74) THEME 8 - CONTEMPLATIVE SOCIETY, 8d - Intellectual Currents UNITED STATLS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC William Monroe Trotter House AND/OR COMMON William Monroe Trotter House LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 97 Sawyer Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Dorchester — VICINITY OF Ninth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Suffolk 025 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM KBUILDING(S) -^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL *_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X.NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME JohnW. and Irene N. Prantis STREET & NUMBER 97 Sawyer Avenue_ CITY. TOWN STATE Dorchester VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE Book 2595, pp. 601-602 REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETc. Regfstry of Deeds, Suffolk County Courthouse Book 3358, pp. 10-11 STREET&CTRPPT «, NUMBERNIIMRFR Pemberton Square CITY, TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS None Known DATE .FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ X_FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The William Monroe Trotter House is a rectangular plan, balloon frame house of the late 1880's or 1890's. The house is set on a foundation of coursed rubble granite, and is covered by a high gabled roof of asphalt shingle. -

Beyond the Civil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications William Monroe Trotter Institute 1-1-1994 Beyond The iC vil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development James Jennings University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_pubs Part of the African American Studies Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Community Engagement Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Jennings, James, "Beyond The ivC il Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development" (1994). William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications. Paper 4. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_pubs/4 This Occasional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the William Monroe Trotter Institute at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 0 D — Occasional Paper No. 29 Beyond The Civil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development by James Jennings 1994 This paper is based on a presentation made at a forum sponsored by the African-American Law and Policy Report, University of California at Berkeley, in January 1994. James Jennings is Professor olPolitical Science and Director of the William Monroe Trotter Institute at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Foreword Through this series of publications the William Monroe Trotter Institute is making available copies of selected reports and papers from research conducted at the Institute, The analyses and conclusions contained in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or endorsement of the Trotter Institute or the University of Massachusetts. -

Download Fact Sheet

WITH ALL THY MIGHT 1 x 90 With All Thy Might: The Battle Against Birth of a Nation is an historical documentary that tells the little-known story of William Monroe Trotter, a fire- breathing editor of a Boston black newspaper who helped launch a nationwide movement in 1915 to ban a flagrantly racist film, The Birth of a Nation. This film tells the story of a black civil rights movement few are familiar with—one that occurred a full 40 years before the one we know. D.W. Griffith’s masterpiece The Birth of a Nation is credited with transforming Hollywood and pioneering many of the techniques that have made the feature film one of America’s most celebrated and widely exported 1 x 90 cultural creations. The movie was also flagrantly racist and glorified the Ku Klux Klan as its central protagonist. But what is neither famous nor infamous is the contact way America reacted to this revolutionary film. While The Birth of a Nation was Tom Koch, Vice President a box office smash that became the first motion picture ever to be screened at PBS International 10 Guest Street the White House, it proved divisive in a country still struggling in the aftermath Boston, MA 02135 USA of Civil War Reconstruction and galvanized leaders of the national African TEL: 617-300-3893 American community into adopting a more aggressive approach in their fight FAX: 617-779-7900 for equality. [email protected] With All Thy Might interweaves the civil rights story of newspaperman pbsinternational.org Trotter and the years leading up to the release of The Birth of a Nation with the story of D.W. -

The Role of Universities in Racial Violence on Campuses Wornie L

Trotter Review Volume 3 Article 2 Issue 2 Trotter Institute Review 3-20-1989 Commentary: The Role of Universities in Racial Violence on Campuses Wornie L. Reed University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review Part of the African American Studies Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Reed, Wornie L. (1989) "Commentary: The Role of Universities in Racial Violence on Campuses," Trotter Review: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review/vol3/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the William Monroe Trotter Institute at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trotter Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commentary The Role of Universities in Racial Violence on Campuses by Wornie L. Reed Racial violence against blacks on college campuses across the country has become a source of consider- able and legitimate concern. This paper reviews the nature and extent of these incidents, discusses the national social context of their occurrence, and ex- amines the role that universities play in the develop- ment of these incidents. The number of racial incidents reported on col- lege campuses in recent years has been on the in- crease. The International Institute Against Prejudice and Violence, located in Baltimore, documented ra- Poverty Law Center indicates that between 1985 and cial incidents at 175 colleges for 1986-87. And, of 1986 there were at least 45 cases of vigilante activi- course, this figure does not adequately reflect the ty directed at black families who were moving into total number of incidents as it is based solely on the predominantly white communities. -

Download As A

The Curious Adventures of William Monroe Trotter production book Judith N. Shklar GIVING INJUSTICE ITS DUE Most injustices occur continuously within the framework of n November 2015, the Black Justice League of Princeton University an established polity with an operative system of law, in I staged a demonstration in an attempt to catch the conscience of our normal times. community. Their message was clear: Black students cannot breathe freely on our campus under the weight of Woodrow Wilson’s legacy. Indeed, Woodrow Wilson was the most prominent intellectual of the white supremacist culture war waged against equal rights for Afro- Americans. Wilson propagated a falsified history of the Civil War and Reconstruction. He also glorified the Ku Klux Klan as the legitimate ruler of the South. As President, Wilson reshaped the federal government to reflect the general will of the Southern whites to dominate Afro- Americans and unleashed a state propaganda machine to change public opinion in the North that hitherto rejected white supremacy. Wilson’s subversive ideas about the sovereignty of the KKK and his opposition to full citizenship for back people on the basis of their racial inferiority were protected by the First Amendment; but they would have been illegal to act upon openly. The estimation of Wilson’s reputation is made difficult by the fact that he had adapted the conspiratorial and deceitful manner of the Southern cultural, political and judicial elite that hid behind the fully disguised, yet spectacularly visible members of the KKK, who did the dirty work for them. Wilson’s white supremacist beliefs cannot be excused by the explanation that he was just a man of his time. -

The Black Press and Its Dialogue with White America, 1914-1919

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1996 "Getting America told": The black press and its dialogue with white America, 1914-1919 William George Jordan University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Jordan, William George, ""Getting America told": The black press and its dialogue with white America, 1914-1919" (1996). Doctoral Dissertations. 1928. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1928 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Reconstruction Time Line with Notes

Reconstruction Time Line with Notes Compiled by Marilyn Mitchell, June 2020 (with edits in October by Karen Wamstad) 1861-1865 Civil War 1861-1865 Abraham Lincoln, President, Republican (Union Party) Elected 1860, reelected 1865 1862 Lincoln considers a reconstruction plan including voting rights for “some” Black Americans 1863 Emancipation Proclamation: An executive order that freed over 3.5 million slaves in Confederate states. 180,000 freed slaves join the Union forces Video #1 1863-1877 Reconstruction (considered to have begun in 1865 at the end of the war) April 9, 1865 Lee surrenders to Grant at Appomattox Court House April 14, 1865 Lincoln assassinated 1865-1869 Andrew Johnson, President, Democrat (Union Party); he was a Southerner but not a member or friend of the plantation elite nor a friend of the Black population May -Dec 1865 Johnsonian Reconstruction. While Congress is not in session Johnson attempts to return South to pre-war status with confederate military officers and plantation owners in leadership positions and the reinstitution of servitude labor May 1865 Freedman’s Bureau created to oversee the transition of Southerners from slavery to freedom, i.e., to protect former slaves and oversee land redistribution June 19,1865 Juneteenth. News of Emancipation Proclamation reaches Galveston Texas. Oct 1865 Parts of SC, GA and FL set aside for freedmen (40 acres and a mule) Dec 1865 Thirteenth Amendment ratified abolishing slavery 1865 Black Codes (restrictive laws designed to limit the freedom of African Americans and ensure their availability as a cheap labor force) passed in Southern states. 1866 Ku Klux Klan organizes. -

Race Leadership Struggle: Background of the Boston Riot of 1903 Author(S): Elliott M

Journal of Negro Education Race Leadership Struggle: Background of the Boston Riot of 1903 Author(s): Elliott M. Rudwick Source: The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Winter, 1962), pp. 16-24 Published by: Journal of Negro Education Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2294533 Accessed: 27-07-2016 01:08 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Negro Education is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Negro Education This content downloaded from 128.210.126.199 on Wed, 27 Jul 2016 01:08:53 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Race Leadership Struggle: Background of the Boston Riot of 1903* ELLIOTT M. RUDWICK Associate Professor of Sociology, Southern Illinois University Booker T. Washington and his dicta- mur! 0 times, 0 evil days, upon which torial Tuskegee Machine were challenged we have fallen! in 1901 by William Monroe Trotter, who Trotter also termed Washington a political founded the Boston Guardian in that boss who masked his machine by pretend- year. However, Trotter and the other ing to be an educator.4 He resented the Negro Radicals were almost completely Tuskegeean's connections with President unsuccessful in placing their case before Roosevelt, because the apostle of indus- the nation until they were able to per- trial education, according to the editor, suade W. -

The Profeminist Politics of W. E. B. Du Bois— With

The Profeminist Politics 6 of W. E. B. Du Bois with Respects to Anna Julia Cooper and Ida B. Wells Barnett Joy James The uplift of women is, next to the problem of the color line and the peace movement, our greatest modern cause. When, now, two of these rnovements- women and color-e-combine in one, the combination has deep meaning. -w. E. B. Du Bois! In the above quote from his 1920 essay, "The Damnation of Women," W. E. B.Du Bois designates the "great causes" as the struggles for racial justice, peace, and women's equality. His use of the phrase "next to" does not refer to a sequential order of descending importance. Concerns for racial equality, international peace, and women's emancipation combined to form the complex, integrative character of Du Bois's analysis. With politics remark- ably progressive for his time, and ours, Du Bois confronted race, class, and gender oppression while maintaining conceptual and political linkages between the struggles to end racism, sexism, and war. He linked his primary concern, ending white supremacy-Souls of Black Folk (1903) defines the color-line as the twentieth century's central problem, to the attainment of ./ international peace and justice. Du Bois wove together an analysis integrating 142 JOY JAMES the various components of African American liberation and world peace. Initially gender, and later economic, analysis were indispensable in developing his political thought. I explore Du Bois's relationship to that «deep meaning" embodied in women and color by examining his representation of African American women and his selective memory of the agency of his contemporaries Anna Julia Cooper and Ida B. -

The Inventory of the Guardian of Boston / William Monroe Trotter

The Inventory of the Guardian of Boston / William Monroe Trotter Collection #455 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Collection on Deposit P.rinted It�� (?") Box 1 1) The Guardi_an. HoJM.+ _'.1 November 9, 1901 Vol� A/a I. July 12, 1919 May 17, 1902 July 19, 1919 June 14, 1902 December 13, 1919 August 30, 1902 January 311 1920 October 4, 1902 January 10, 1920 . November l, 1902 January 20�!il920 November 29, 1902 February 7, 1920 December 6, 1902 December �O, 1932 October 10, 1903 January 20, 1923 December 16, 1905 Harch 21, 1923 {2 tepties) April 7, 1923 February 23 9 1907 April 28• 1923 April 27, 1912 Hay 4, 1912 June 29, 1912 June 30, 1923 · Januar_y /+• 1913 July 28 t 1923 June 7, 1913 (15 copies) November 20, 1915 July 12, 1924 February 19, 1916 August 26, 1933 November 18, 1916 February 17, 1934 December 2, 1916 Apt·il 7, 1934 April 12, 1919 April 14, 1934 'May 16, 1919 (5 copies) April 21 • 1934 Box 2 June 11+ � 1919 (2 copies) p1:1.ge 2 April 28, 1934 May .5, 1934 October.23, 1954 May 12, 1934 November 20, 1954 (2 dopies) Box 3 May 26. 1934 Decen1ber 18, 1951+ Junca 2, 1934 (2 copies) June 23, 1914 September 10, 1955 June 3 19.34 November 5, 1955 0, (3 copies) July 7, 1934 November 12, 1955 November 10, 1934 (3 copies) November 2J 1935 January 7 $ 1956 June 26, 1937 March 3 t 1956 .Does not appear on June 4, 1938 (Gift 9f Mrs. -

William Monroe Trotter: a Twentieth Century Abolitionist William A

Trotter Review Volume 2 Article 6 Issue 1 Trotter Institute Review 1-1-1988 William Monroe Trotter: A Twentieth Century Abolitionist William A. Edwards University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review Part of the African American Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, William A. (1988) "William Monroe Trotter: A Twentieth Century Abolitionist," Trotter Review: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review/vol2/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the William Monroe Trotter Institute at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trotter Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William Monroe Trotter: A Twentieth Century Abolitionist by William A. Edwards Historians have generally referred to the turn of the twen- the ascendancy of Mr. Booker T. Washington."2 At least tieth century as the Progressive Era. As one historian has two other historians have characterized the period from observed: 1880 to 1915 as the "Age of Booker Washington." 3 Wash- ington's philosophy of racial accommodationism, grad- It was not ... so much the movement of any social ualism and industrial education influenced an interna- class, or coalition of classes, against a particular tional agenda regarding blacks. His influence in this class or group as it was a . widespread and re- country made him an unparalleled force in the national markably good-natured effort of the greater part of debate on the "Negro Question." He dominated the na- society to achieve some not very clearly specified tional consciousness on race relations to the extent that 1 self-reformation. -

Tell the Story

NEWS & NOTES the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and a Freedom Rider Take Heart, who was jailed for her civil rights activism in the 1960s. Tell the Story Preacely says her mother, the late Ellen Craft Dammond, was “the griot of the family” and shared the oral history that had been passed down to her from her own mother and older relatives. Family lore connected them to Monticello, says Preacely, but no one was sure Peggy Preacely of exactly how. That changed in 2004, when a Thad Jackson Thad historian with the Getting Word African American Getting Word Project Shares the Oral History Project contacted the family. Getting Word began in 1993, led by Lucia “Cinder” Voices of Descendants of Stanton and another Monticello historian, Dianne Swann- Monticello’s Enslaved Families Wright. They sought out the descendants of Monticello’s enslaved families in an effort to learn a more complete By Samantha Willis story of the plantation. The histories Whenever Peggy Dammond Preacely speaks about her recorded by the project represent the ancestors, including her kin who were enslaved at Thomas diverse experiences and legacies of Jefferson’s Monticello hundreds of years ago, she first asks Monticello’s African American families, their permission. and the indelible impression they left on “I always, always get their blessing before I tell their story,” American history. she says, adding that she usually performs an African libation “I and my family have celebrated ritual in their honor. “My mother taught me the importance Getting Word’s attempt to rewrite history of keeping our people’s story sacred.” correctly by giving credence and a voice to Preacely’s lineage is legendary.