An Evaluation of President Woodrow Wilson with Regard to Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Form

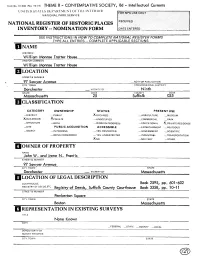

Form NO. 10-300 (Rav. 10-74) THEME 8 - CONTEMPLATIVE SOCIETY, 8d - Intellectual Currents UNITED STATLS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC William Monroe Trotter House AND/OR COMMON William Monroe Trotter House LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 97 Sawyer Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Dorchester — VICINITY OF Ninth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Suffolk 025 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM KBUILDING(S) -^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL *_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X.NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME JohnW. and Irene N. Prantis STREET & NUMBER 97 Sawyer Avenue_ CITY. TOWN STATE Dorchester VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE Book 2595, pp. 601-602 REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETc. Regfstry of Deeds, Suffolk County Courthouse Book 3358, pp. 10-11 STREET&CTRPPT «, NUMBERNIIMRFR Pemberton Square CITY, TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS None Known DATE .FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ X_FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The William Monroe Trotter House is a rectangular plan, balloon frame house of the late 1880's or 1890's. The house is set on a foundation of coursed rubble granite, and is covered by a high gabled roof of asphalt shingle. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

The Progressive Movement and the Reforming of the United States of America, from 1890 to 1921

2014 Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria. Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. University of Oran. Faculty of Letters, Languages, and Arts. Department of English. Research Paper Submitted for a Doctorate Thesis in American Civilisation Entitled: The Progressive Movement and the Reforming of the United States of America, from 1890 to 1921. Presented by: Benketaf, Abdel Hafid. Jury Members Designation University Pr. Bouhadiba, Zoulikha President Oran Pr. Borsali, Fewzi Supervisor Adrar Pr. Bedjaoui, Fouzia Examiner 1 Sidi-Belabes Dr. Moulfi, Leila Examiner 2 Oran Dr. Belmeki, Belkacem Examiner 3 Oran Dr. Afkir, Mohamed Examiner 4 Laghouat Academic Year: 2013-2014. 1 Acknowledgements Acknowledgments are gratefully made for the assistance of numerous friends and acquaintances. The largest debt is to Professor Borsali, Fewzi because his patience, sound advice, and pertinent remarks were of capital importance in the accomplishment of this thesis. I would not close this note of appreciation without alluding to the great aid provided by my wife Fatima Zohra Melki. 2 Dedication To my family, I dedicate this thesis. Pages Contents 3 List of Tables. ........................................................................................................................................................................ vi List of Abbreviations......................................................................................................................................................... vii Introduction. ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Beyond the Civil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications William Monroe Trotter Institute 1-1-1994 Beyond The iC vil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development James Jennings University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_pubs Part of the African American Studies Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Community Engagement Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Jennings, James, "Beyond The ivC il Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development" (1994). William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications. Paper 4. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_pubs/4 This Occasional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the William Monroe Trotter Institute at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 0 D — Occasional Paper No. 29 Beyond The Civil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development by James Jennings 1994 This paper is based on a presentation made at a forum sponsored by the African-American Law and Policy Report, University of California at Berkeley, in January 1994. James Jennings is Professor olPolitical Science and Director of the William Monroe Trotter Institute at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Foreword Through this series of publications the William Monroe Trotter Institute is making available copies of selected reports and papers from research conducted at the Institute, The analyses and conclusions contained in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or endorsement of the Trotter Institute or the University of Massachusetts. -

10-821-Amici-Brief-S

NO. 10-821 In the Supreme Court of the United States PAT QUINN, GOVERNOR OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS, Petitioner, v. GERALD JUDGE, DAVID KINDLER, AND ROLAND W. BURRIS, U.S. SENATOR, Respondents. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit BRIEF OF THE STATES OF LOUISIANA, COLORADO, IOWA, KENTUCKY, MAINE, MARYLAND, MASSACHUSETTS, MISSOURI, NEW MEXICO, NEVADA, OHIO, SOUTH CAROLINA, AND UTAH, AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER JAMES D. “BUDDY” CALDWELL Louisiana Attorney General JAMES T REY P HILLIPS First Assistant Attorney General S. KYLE DUNCAN* Appellate Chief ROSS W. BERGETHON Assistant Attorney General LOUISIANA D EPARTMENT OF J USTICE P.O. BOX 94005 BATON ROUGE, LA 70804-9005 (225) 326-6716 [email protected] Counsel for State Amici Curiae January 21, 2011 *Counsel of Record [additional counsel listed on inside cover] Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 John W. Suthers Chris Koster Attorney General of Colorado Attorney General of Missouri 1525 Sherman St. 207 West High Street Denver, Colorado 80203 Jefferson City, Missouri 65101 Tom Miller Gary K. King Attorney General of Iowa Attorney General of 1305 East Walnut St. New Mexico Des Moines, Iowa 50319 P.O. Drawer 1508 Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504- Jack Conway 1508 Attorney General of Kentucky 700 Capitol Avenue, Suite 118 Catherine Cortez Masto Frankfort, Kentucky Attorney General of Nevada 100 North Carson Street William J. Schneider Carson City, Nevada 89701 Attorney General of Maine Six State House Station Michael DeWine Augusta, Maine 04333 Ohio Attorney General 30 E. -

Download Fact Sheet

WITH ALL THY MIGHT 1 x 90 With All Thy Might: The Battle Against Birth of a Nation is an historical documentary that tells the little-known story of William Monroe Trotter, a fire- breathing editor of a Boston black newspaper who helped launch a nationwide movement in 1915 to ban a flagrantly racist film, The Birth of a Nation. This film tells the story of a black civil rights movement few are familiar with—one that occurred a full 40 years before the one we know. D.W. Griffith’s masterpiece The Birth of a Nation is credited with transforming Hollywood and pioneering many of the techniques that have made the feature film one of America’s most celebrated and widely exported 1 x 90 cultural creations. The movie was also flagrantly racist and glorified the Ku Klux Klan as its central protagonist. But what is neither famous nor infamous is the contact way America reacted to this revolutionary film. While The Birth of a Nation was Tom Koch, Vice President a box office smash that became the first motion picture ever to be screened at PBS International 10 Guest Street the White House, it proved divisive in a country still struggling in the aftermath Boston, MA 02135 USA of Civil War Reconstruction and galvanized leaders of the national African TEL: 617-300-3893 American community into adopting a more aggressive approach in their fight FAX: 617-779-7900 for equality. [email protected] With All Thy Might interweaves the civil rights story of newspaperman pbsinternational.org Trotter and the years leading up to the release of The Birth of a Nation with the story of D.W. -

H. Doc. 108-222

OFFICERS OF THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH OF THE GOVERNMENT [ 1 ] EXPLANATORY NOTE A Cabinet officer is not appointed for a fixed term and does not necessarily go out of office with the President who made the appointment. While it is customary to tender one’s resignation at the time a change of administration takes place, officers remain formally at the head of their department until a successor is appointed. Subordinates acting temporarily as heads of departments are not con- sidered Cabinet officers, and in the earlier period of the Nation’s history not all Cabinet officers were heads of executive departments. The names of all those exercising the duties and bearing the respon- sibilities of the executive departments, together with the period of service, are incorporated in the lists that follow. The dates immediately following the names of executive officers are those upon which commis- sions were issued, unless otherwise specifically noted. Where periods of time are indicated by dates as, for instance, March 4, 1793, to March 3, 1797, both such dates are included as portions of the time period. On occasions when there was a vacancy in the Vice Presidency, the President pro tem- pore is listed as the presiding officer of the Senate. The Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution (effective Oct. 15, 1933) changed the terms of the President and Vice President to end at noon on the 20th day of January and the terms of Senators and Representatives to end at noon on the 3d day of January when the terms of their successors shall begin. [ 2 ] EXECUTIVE OFFICERS, 1789–2005 First Administration of GEORGE WASHINGTON APRIL 30, 1789, TO MARCH 3, 1793 PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—GEORGE WASHINGTON, of Virginia. -

America's Money Machine: the Story of the Federal Reserve

AMERIC~S MONEY MACHINE BOOKS BY ELGIN GROSECLOSE Money: The Human Conflict (I934) The Persian Journey ofthe Reverend Ashley Wishard and His Servant Fathi (I937) Ararat (I939, I974, I977) The Firedrake (I942) Introduction to Iran (I947) The Carmelite (I955) The Scimitar ofSaladin (I956) Money and Man (I96I, I967, I976) Fifty Years ofManaged Money (I966) Post-War Near Eastern Monetary Standards (monograph, I944) The Decay ofMoney (monograph, I962) Money, Man and Morals (monograph, I963) Silver as Money (monograph, I965) The Silken Metal-Silver (monograph, I975) The Kiowa (I978) Olympia (I98o) AMERIC~S MONEY MACHINE The Story of the Federal Reserve Elgin Groseclose, Ph.D. Prepared under the sponsorship of the Institute for Monetary Research, Inc., Washington, D. C. Ellice McDonald, Jr., Chairman A Arlington House Publishers Westport, Connecticut An earlier version of this book was published in 1966 by Books, Inc., under the title Fifty Years of Managed Money Copyright © 1966 and 1980 by Elgin Groseclose All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in connection with a review. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Groseclose, Elgin Earl, 1899 America's money machine. Published in 1966 under title: Fifty years of managed money, by Books, inc. Bibliography: P. Includes index. 1. United States. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System-History. I. Title. HG2563·G73 1980 332.1'1'0973 80-17482 ISBN 0-87000-487-5 Manufactured in the United States of America P 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For My Beloved Louise with especial appreciation for her editorial assistance and illuminating insights that gave substance to this work CONTENTS Preface lX PART I The Roots of Reform 1. -

![1944-10-13, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6784/1944-10-13-p-3356784.webp)

1944-10-13, [P ]

Friday, October 13, 1944 THE TOLEDO UNION JOURNAL r Si wewoiialirossiii <*< Mv**™?*! i ■ ■■-a- ..........................- ..... ...................................................................... 1 “Greenwich Villas’ With Laughs, S^ngs *1 Now, with the showing of 20th Century-Fox’s new Techni color musical, “Greenwich Village,” audiences at the Paramount Theatre were treated to the merriest Mardi-Gras of laughs, tunes, romantic doings and gay spectacle to hit a local screen in a long, long time. And mighty welcome it was, too. Apparently, always more than a step ahead of the field in mu- Heard On a Hollywood sicals, 20th Century-Fox has really “shot the works” on this Movie Set one, including the stand-out cast HOLLYWOOD—It was a starring Carmen Miranda, Don fjtiitt moment on the set of Ameche, William Bendix and the new production dealing IT'S Vivian Blaine, “The Cherry with the Women’s Army Blonde” a perfect dream of a Corps. Technical Advisor, (You’ll «ee all yo^ production, and the most daz Lieut. Louise White was 'M zling Technicolor this side of surprised by stars Lana favorite ^ars.') heaven. The film is packed tight Turner, Laraine Day, Su with more thrills than a Mardi- san Peters, and a group of Gras, more gals than a harem, girls representing WAC’s. more songs than a flock of She was discussing the cur mocking birds, and solid, down rent recruiting drive which right fun that reaches a new must enlist 5,000 WAC’s high in hilarious entertainment. from California before the end of December. (You’ll hear 0,1 yOUf Anything can—and docs— favorite hit tunes!) o happen in “Greenwich Village”. -

Wall Street, Banks, and American Foreign Policy: Second Edition

W S, B, A F P W S, B, A F P S E M N. R W I A G J R First appeared in World Market Perspective (1984) and later under the same title as a monograph produced by the Center for Libertarian Studies (1995) Ludwig von Mie Intitute AUBURN,ALABAMA Copyright © 2011 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute Published under the Creative Commons Aribution License 3.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Ludwig von Mises Institute 518 West Magnolia Avenue Auburn, Alabama 36832 mises.org ISBN: 978-1-61016-192-3 Contents Introduction to the 2011 Edition vii Introduction to the 1995 Edition xxi Wall Street, Banks, and American Foreign Policy 1 J. P. Morgan 3 An Aggressive Asian Policy 9 Teddy Roosevelt and the “Lone Nut” 13 Morgan, Wilson, and War 17 e Fortuitous Fed 25 e Round Table 29 e CFR 31 Roefeller, Morgan, and War 33 e Guatemalan Coup 43 JFK and the Establishment 47 LBJ and the Power Elite 51 Henry A. Kissinger 57 e Trilateral Commission 61 Bibliography 69 Index 71 v Introduction to the 2011 Edition By Anthony Gregory e idea that corporate interests, banking elites and politicians conspire to set U.S. policy is at once obvious and beyond the pale. Everyone knows that the military-industrial complex is fat and corrupt, that presidents bestow money and privilege on their donors and favored businesses, that a revolving door connects Wall Street and the White House, that economic motivations lurk behind America’s wars. But to make too fine a point of this is typically dismissed as unserious conspiracy theorizing, unworthy of mainstream consideration. -

Rsmmkss Reaved

A-18** THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18. 1953 Judge Praetor Dies; Mrs. Brice Clagett William 6. Shea, 74, Delayed Stickers to Be Ready Htratilittg Bratlffl Veteran Union Leader By BREESKIN. DANIEL »nd ROSE. Friends s JACKSON. EMMA. On Monday. Sep- Jurist Served With Dies in Hospital After tho Associated Frtss Tomorrow in Traffic Campaign and relatives are invited to the unveil- tember 14. 1953. at Georgetown Uni- ing services of the late DANIEL and i versity Hospital. EMMA JACKSON, lov- LOUISVILLE, Ky., Sept. 18— A minor printing mixup has i! The Metropolitan Police De- ROSE BREESKIN on Sundajr. Septem- - lng wife of Isaac Jackson of Baileys ifii- MllF William G. Shea, “grand old ber "0, 1 nr>a. at 2 p.m.. at the George e Crossroads. Va. Many other relatives delayed distribution of the Traf- jj partment also was asked to have Cemetery. j Years Washington Tifereth Israel 1 and friends also survive. Friends are Distinction 22 Accident on Street man” of the Brotherhood of accident investigation Riggs fle Safety uhit Section. rd. extended. Silverr Invited to call at the Chinn Funeral Paper Crusade window stick- Spring. Md. 19 Home. 2606 South Seminary rd.. Ar- Judge James M. Proctor, a Mrs. Brice Clagett. widow of Painters, Decorators and i policemen distribute the pledges lington, Va.. after 6 p.m. Friday. Sep- Hangers, died yesterday of a ers, but it was expected to be to involved BVCKHAXTZ. MRS. BERTHA. A monu- tember 18. Funeral services at 1 p.m. noted jurist here for more than Judge Clagett of the Municipal persons in accidents ment unveiling the Mrs. -

Copyright By- David Henry Jennings

Copyright by- David Henry Jennings 1959 PRESIDENT WILSON'S TOUR IN SEPTEMBER, 1919: A STUDY OF FORCES OPERATING DURING THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS FIGHT DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University t By DAVID HENRY JENNINGS, B. A ., A. M. ****** The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by A dviser Department of History PREFACE In view of the many articles and books occasioned by the recent Wilson Centennial and the current in te re st in American foreign policy, it is, indeed, surprising to note that no full length study of Wilson's transcontinental tour of September, 1919 exists. Present publication on the western trip is confined to individual chapters of longer works and b rief general essays.^ A communication from Arthur S. Link indicates that this topic w ill not receive extended coverage in his future volumes on Woodrow Wilson. The status of research indicates the need for a more complete account of the "Swing Around the Circle" than has hitherto been presented. It is hoped that this dissertation meets this need. The other major contribution of this thesis lies in the field of evaluation. The analysis of Wilson's "New Order" attempts to make a significant clarifi cation and synthesis in a relatively neglected area. The study, also, endeavors to identify the forces at work and appraise their effect on the League of Nations debate in September, 1919. Because present day opinion inclines toward the view that the transcontinental tour was a mistake, extended examination is undertaken to see why Wilson should have gone on the trip and why the tour failed.