William Monroe Trotter: a Twentieth Century Abolitionist William A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garland's Million: the Radical Experiment To

October 14, 2019 To: ABF Legal History Seminar From: John Fabian Witt Re: October 23 seminar Thanks so much for looking at my drafts and coming to my session! I’m thrilled to have been invited to Chicago. I am attaching chapters 5 and 8 from my book-in-progress, tentatively titled Garland’s Million: The Radical Experiment to Save American Democracy. The book is the story of an organization known informally as the Garland Fund or formally as the American Fund for Public Service: a philanthropic foundation established in 1922 to give money to liberal and left causes. The Fund figures prominently in the history of civil rights lawyering because of its role setting in motion the early stages of the NAACP’s litigation campaign that led a quarter-century later to Brown v. Board of Education. I hope you will be able to get some sense of the project from the crucial chapters I’ve attached here. These chapters come from Part 2 of the book. Part 1 focuses on Roger Baldwin, the founder of the ACLU and the principal energy behind the Fund. Part 2 (including the chapters here) focuses on James Weldon Johnson, who ran the NAACP during the 1920s and was a board member of the Fund. Parts 3 and 4 turn respectively to Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (a labor radical on the board) and Felix Frankfurter, who in the 1920s served as a key outside consultant and counsel to the Fund. To set the stage, readers have learned in Part 1 about Baldwin as a disillusioned reformer, who advocated progressive programs like the initiative and referendum only to see direct democracy produce a wave of white supremacist initiatives. -

The Negro Press and the Image of Success: 1920-19391 Ronald G

the negro press and the image of success: 1920-19391 ronald g. waiters For all the talk of a "New Negro," that period between the first two world wars of this century produced many different Negroes, just some of them "new." Neither in life nor in art was there a single figure in whose image the whole race stood or fell; only in the minds of most Whites could all Blacks be lumped together. Chasms separated W. E. B. DuBois, icy, intellectual and increasingly radical, from Jesse Binga, prosperous banker, philanthropist and Roman Catholic. Both of these had little enough in common with the sharecropper, illiterate and bur dened with debt, perhaps dreaming of a North where—rumor had it—a man could make a better living and gain a margin of respect. There was Marcus Garvey, costumes and oratory fantastic, wooing the Black masses with visions of Africa and race glory while Father Divine promised them a bi-racial heaven presided over by a Black god. Yet no history of the time should leave out that apostle of occupational training and booster of business, Robert Russa Moton. And perhaps a place should be made for William S. Braithwaite, an aesthete so anonymously genteel that few of his White readers realized he was Black. These were men very different from Langston Hughes and the other Harlem poets who were finding music in their heritage while rejecting capitalistic America (whose chil dren and refugees they were). And, in this confusion of voices, who was there to speak for the broken and degraded like the pitiful old man, born in slavery ninety-two years before, paraded by a Mississippi chap ter of the American Legion in front of the national convention of 1923 with a sign identifying him as the "Champeen Chicken Thief of the Con federate Army"?2 In this cacaphony, and through these decades of alternate boom and bust, one particular voice retained a consistent message, though condi tions might prove the message itself to be inconsistent. -

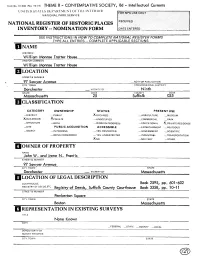

Nomination Form

Form NO. 10-300 (Rav. 10-74) THEME 8 - CONTEMPLATIVE SOCIETY, 8d - Intellectual Currents UNITED STATLS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC William Monroe Trotter House AND/OR COMMON William Monroe Trotter House LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 97 Sawyer Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Dorchester — VICINITY OF Ninth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Suffolk 025 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM KBUILDING(S) -^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL *_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X.NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME JohnW. and Irene N. Prantis STREET & NUMBER 97 Sawyer Avenue_ CITY. TOWN STATE Dorchester VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE Book 2595, pp. 601-602 REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETc. Regfstry of Deeds, Suffolk County Courthouse Book 3358, pp. 10-11 STREET&CTRPPT «, NUMBERNIIMRFR Pemberton Square CITY, TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS None Known DATE .FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ X_FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The William Monroe Trotter House is a rectangular plan, balloon frame house of the late 1880's or 1890's. The house is set on a foundation of coursed rubble granite, and is covered by a high gabled roof of asphalt shingle. -

The Crisis, Vol. 1, No. 2. (December, 1910)

THE CRISIS A RECORD OF THE DARKER RACES Volume One DECEMBER, 1910 Number Two Edited by W. E. BURGHARDT DU BOIS, with the co-operation of Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, VV. S. Braithwaite and M. D. Maclean. CONTENTS Along the Color Line 5 Opinion . 11 Editorial ... 16 Cartoon .... 18 By JOHN HENRY ADAMS Editorial .... 20 The Real Race Prob lem 22 By Profeaor FRANZ BOAS The Burden ... 26 Talks About Women 28 By Mn. J. E. MILHOLLAND Letters 28 What to Read . 30 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE National Association for the Advancement of Colored People AT TWENTY VESEY STREET NEW YORK CITY ONE DOLLAR A YEAR TEN CENTS A COPY THE CRISIS ADVERTISER ONE OF THE SUREST WAYS TO SUCCEED IN LIFE IS TO TAKE A COURSE AT The Touissant Conservatory of Art and Music 253 West 134th Street NEW YORK CITY The most up-to-date and thoroughly equipped conservatory in the city. Conducted under the supervision of MME. E. TOUISSANT WELCOME The Foremost Female Artist of the Race Courses in Art Drawing, Pen and Ink Sketching, Crayon, Pastel, Water Color, Oil Painting, Designing, Cartooning, Fashion Designing, Sign Painting, Portrait Painting and Photo Enlarging in Crayon, Water Color, Pastel and Oil. Artistic Painting of Parasols, Fans, Book Marks, Pin Cushions, Lamp Shades, Curtains, Screens, Piano and Mantel Covers, Sofa Pillows, etc. Music Piano, Violin, Mandolin, Voice Culture and all Brass and Reed Instruments. TERMS REASONABLE THE CRISIS ADVERTISER THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION for the ADVANCEMENT of COLORED PEOPLE OBJECT.—The National Association COMMITTEE.—Our work is car for the Advancement of Colored People ried on under the auspices of the follow is an organization composed of men and ing General Committee, in addition to the women of all races and classes who be officers named: lieve that the present widespread increase of prejudice against colored races and •Miss Gertrude Barnum, New York. -

Strong Men, Strong MINDS

STRONG MEN, STRONG MINDS A DISCUSSION ABOUT EMPOWERING AND UPLIFTING THE BLACK COMMUNITY JOIN US at 2 pm Saturday, August 1, 2020 facebook.com/IndyRecorder Moderator: Panelist: Panelist: Panelist: Panelist: Larry Smith Kenneth Allen Keith Graves Minister Nuri Muhammad Clyde Posley Jr., Ph.D. Community Servant Chairman Indianapolis City-County Speaker, Author Senior Pastor Indianapolis Recorder Indiana Commission on the Council District 13 Community Organizer Antioch Baptist Church Newspaper Columnist Social Status of Black Males Mosque #74 Indiana’s Greatest Weekly Newspaper Preparing a conscious community today and beyond Friday, July 31, 2020 Since 1895 www.indianapolisrecorder.com 75 cents ‘Elicit a change’: protests then and now By BREANNA COOPER [email protected] Mmoja Ajabu was 19 when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. He was in the military at the time, in training in Missouri. He and the other Black soldiers in his base were Taran Richardson (left) stands relegated to a remote part of the with Kelli Marshall, who previously base and told they would be shot worked at Tindley Accelerated Schools, where Richardson gradu- if they attempted to leave as the ated from this year. Richardson white soldiers went out to “quell plans to attend Howard University the rebellion in St. Louis,” he said. in the fall to study astrophysics. (Photo provided) “I started understanding at that point what the hell was going on,” Ajabu said. Tindley grad ready NiSean Jones, founder of Black Out for Black Lives, addresses a for a new challenge See PROTESTS, A5® crowd downtown on June 19. (Photo/Tyler Fenwick) IPS MAY VOTE TO at Howard University CHANGE COURSE By TYLER FENWICK [email protected] By STAFF Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS) When Taran Richardson was in high could change course and go to e- school at Tindley Accelerated Schools, learning for all students instead of he developed an appropriate motto for giving students the option of vir- himself: #NoSleepInMySchedule. -

The Birth of a Nation : How a Legendary Director and A

5>.. K' •.— •*-,X DICK LEHR $26.99/$30.oo can “By telling the story of the sweeping and headline-making cultural clash between filmmaker D. W. Griffith and brave newspaperman Monroe Trotter—and telling it with brio and panache—the gifted Dick Lehr should be highly commended. This book is both timely and important.” —WIL HAYGOOD, author of In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr. IN 1915, TWO MEN—ONE A JOURNALIST AGITATOR, the other a technically brilliant filmmaker—incited a public confrontation that roiled America, pitting black against white, Hollywood against Boston, and free speech against civil rights. Monroe Trotter and D. W. Griffith were fighting over a film that dramatized the Civil War and Reconstruction in a post-Confederate South. Almost fifty years earlier, Monroe’s father, James, was a sergeant in an all-black Union regiment that marched into Charleston, South Carolina, just as the Kentucky cavalry—including Roaring Jack Griffith, D. W.’s father—^fled for their lives. Griffith’s film. The Birth of a Nation, included actors in blackface, heroic portraits of Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and a depiction of Lincoln’s assassination. Freed slaves were portrayed as villainous, vengeful, slovenly, and dangerous to the sanctity of American values. It was tremendously successful, eventually seen by 25 million Americans. But violent protests against the film flared up across the country. Monroe Trotter’s titanic crusade to have the film censored became a blueprint for dissent during the 1950s and 1960s. This is the fiery story of a revolutionary moment for mass media and the nascent civil rights movement, and the men clashing over the cultural and political soul of a still-young America standing at the cusp of its greatest days. -

The Niagara Movement Commemoration at Harpers Ferry

Published for the Members and Friends IN THIS ISSUE: of the Harpers Ferry August 18, 19 & 20 Historical Association Niagara Movement Summer 2006 Commemoration Events Niagara Academic Symposium 1906 - 2006 2006 Park Schedule The Niagara Movement Commemoration of Events at Harpers Ferry The History In August 1906, a momentous event took place on the Storer College Campus in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Little-known and not frequently mentioned in history books, this event and its signifi- cance reached far into the new century to lay the groundwork for the formation of the NAACP and the Civil Rights Movement. The Niagara Convention held its first public meeting in the United States on August 15 - 19, 1906 on the campus of Storer College. This August, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park will commemorate the 100th anniversary of this his- toric meeting with a week of activities of Niagarites adopted a constitution and by- Delegates to the Second celebration, inspiration and remembrance. laws, established committees, and wrote the Niagara Movement This event is being hosted by Harpers Ferry “Declaration of Principles” outlining the Conference pose in front of NHP and co-sponsored by the Jefferson future for African Americans. They planned Anthony Hall on the Storer County Branch of the NAACP and the for annual conferences in locations that had College campus on August 17, Harpers Ferry Historical Association. significance to the freedom struggle. 1906 (Harpers Ferry National With failed Reconstruction, the Su- Thirteen months later, they chose Historical Park). preme Court’s separate but equal doctrine, Harpers Ferry as their meeting place. Be- and Booker T. -

WEB Du Bois and the Rhetoric of Social Change, 1897-1907

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2008 W.E.B. Du Bois and the Rhetoric of Social Change, 1897-1907: Attitude as Incipient Action Fendrich Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Clark, F. (2008). W.E.B. Du Bois and the Rhetoric of Social Change, 1897-1907: Attitude as Incipient Action (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/415 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. W.E.B. DU BOIS AND THE RHETORIC OF SOCIAL CHANGE, 1897-1907: ATTITUDE AS INCIPIENT ACTION A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Fendrich R. Clark May 2009 Copyright by Fendrich R. Clark 2009 W.E.B. DU BOIS AND THE RHETORIC OF SOCIAL CHANGE, 1897-1907: ATTITUDE AS INCIPIENT ACTION By Fendrich R. Clark Approved November 14, 2008 _________________________________ _________________________________ Richard H. Thames, Ph.D. Janie Harden Fritz, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Communication Associate Professor of Communication (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) _________________________________ Pat Arneson, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Communication (Committee Member) _________________________________ _________________________________ Albert C. Labriola, Ph.D. Ronald C. Arnett, Ph.D. Acting Dean, McAnulty College and Professor and Chair, Department of Graduate School of Liberal Arts Communication and Rhetorical Studies (External Member) iii ABSTRACT W.E.B. -

Niagara, the Birth of the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introductory Overview and Resources

Copyright © 2005 – Charles D’Aniello. All rights reserved. This document, either in whole or in part, may NOT be copied, reproduced, republished, uploaded, posted, transmitted, or distributed in any way, except that you may download one copy of it on any single computer for your personal, non-commercial home use only, provided you keep intact this copyright notice. Niagara, The Birth of the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introductory Overview and Resources Charles D'Aniello Associate Librarian Arts and Sciences Libraries State University of New York at Buffalo Part One: Introductory Overview (Note: Hyperlinks are to some of the resources freely available on the World Wide Web; however, please review the many resources that follow this essay. The “overview” is intended as an introduction and is based on the secondary sources “cited” throughout the guide and in the essay itself.) The Niagara Movement (overview sources, 1, 2, 3, 4 select 2005 Summer/Fall) – the immediate “informal” predecessor of the NAACP – had a Buffalo connection. The organizational meeting that preceded its first gathering was held in July 1905 in the Buffalo home of William H. and Mary Burnett Talbert (1865-1923). Today a building on the University at Buffalo North Campus is named in Mary Talbert’s honor, Talbert Hall. Its driving force was sociologist and activist W.E.B. Du Bois (1868- 1963). Du Bois was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University (history, 1895). His dissertation on the suppression of the African slave trade to the United States, 1638-1870, was published in 1896 as the first volume in the Harvard Historical Studies Series. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

OPINIONS AND ACTIVITIES OF THE BLACK COMMUNITY DURING WORLD WAR II AS SEEN IN THE BLACK PRESS AND RELATED SOURCES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY BERNADETTE EILEEN SHEPARD DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA DECEMBER 1974 U TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. BLACKS ON THE HOME FRONT 12 War Industries and Jobs 17 III. TREATMENT OF BLACKS IN THE ARMED FORCES . 27 Enlistment and Training • 28 Incidents of Prejudices in the Armed Forces 40 CONCLUSION 44 BIBLIOGRAPHY 47 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The first World War provided the tide of protest upon which the Black Press rose in importance and in militancy. It was largely the Black press that made Blacks fully conscious of the inconsistency between America's war aims to "make the world safe for "demo cracy" and her treatment of this minority at home. The Second World War again increased unrest, suspicion, and dissatisfaction among Blacks. lit stimulated great interest of the Black man in his press and the fact that the depression was just about over made it possible for him to translate this interest into financial support. By the outbreak of the war many Black newspapers had become economically able to send their own corres pondents overseas. In addition, the Chicago Defender; the Baltimore Afro-American and the Norfolk Journal and Guide had special correspondents who traveled from camp 3-Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma (New York: Harper and Row, 1944), p. 914. 2Vishnu V. -

Beyond the Civil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications William Monroe Trotter Institute 1-1-1994 Beyond The iC vil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development James Jennings University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_pubs Part of the African American Studies Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Community Engagement Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Jennings, James, "Beyond The ivC il Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development" (1994). William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications. Paper 4. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_pubs/4 This Occasional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the William Monroe Trotter Institute at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 0 D — Occasional Paper No. 29 Beyond The Civil Rights Agenda for Blacks: Principles for the Pursuit of Economic and Community Development by James Jennings 1994 This paper is based on a presentation made at a forum sponsored by the African-American Law and Policy Report, University of California at Berkeley, in January 1994. James Jennings is Professor olPolitical Science and Director of the William Monroe Trotter Institute at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Foreword Through this series of publications the William Monroe Trotter Institute is making available copies of selected reports and papers from research conducted at the Institute, The analyses and conclusions contained in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or endorsement of the Trotter Institute or the University of Massachusetts. -

Download Download

W. E. B. Du Bois, F. B. Ransom, the Madam Walker Company, and Black Business Leadership in the 1930s Mark David Higbee" From the 1870s to the 1930s, the development of business en- terprise was widely seen as the one essential ingredient for Afri- can-American progress. Yet neither African-American business enterprise nor the political roles of black entrepreneurs have been adequately studied by historians. Accounts of African-American ec- onomic hardships during the Great Depression have slighted the important political debates that these hardships produced. Simi- larly, writings on W. E. B. Du Bois, the black scholar and founder of the twentieth-century civil rights protest tradition, have ne- glected his distinctive vision of African-American business enter- prise. Consequently, a little known 1937-1938 dispute between Du Bois and Freeman B. Ransom, an African-American businessman and Indianapolis community leader, demands attention. Ransom and Du Bois viewed the proper aims of business enterprise in rad- ically opposing ways. The Ransom-Du Bois dispute provides an op- portunity to examine the differing ways these two leaders approached the problems of the Depression as well as how African Americans reconsidered older ideas of black business enterprise and political leadership. Studying the 1930s is acutely important because during that decade faith in business as the basis for Afri- can-American leadership was supplanted by political and labor strategies. * Mark Higbee is completing a dissertation on W.E.B. Du Bois at Columbia University, New York. He thanks the following people for their comments on vari- ous drafts of this essay: Barbara Bair, Eric Bates, Martha Biondi, Jonathan Bir- enbaum, Elizabeth Blackmar, Eric Foner, Wilma Gibbs, Sarah Henry, Kate Levin, Judith Stein, the members of Col'umbia University's U.S.