Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER Winter/ Spring 2020 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research NEWSLETTER winter/ spring 2020 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, launch May 1 with an event at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. YIVO is thriving. 2019 was another year of exciting growth. Work proceeded on schedule for the Edward Other highlights include a fabulous segment on Mashable’s Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections and we anticipate online “What’s in the Basement?” series; a New York completion of this landmark project in December 2021. Times feature article (June 25, 2019) on the acquisition Millions of pages of never-before-seen documents and of the archive of Nachman Blumenthal; a Buzzfeed rare or unique books have now been digitized and put Newsletter article (December 22, 2019) on Chanukah online for researchers, teachers, and students around the photos in the DP camps; and a New Yorker article world to read. The next important step in developing (December 30, 2019) on YIVO’s Autobiographies. YIVO’s online capabilities is the creation of the Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum of East YIVO is an exciting place to work, to study, to European Jewish Life. The museum will launch early explore, and to reconnect with the great treasures 2021. The first gallery, devoted to the autobiography of the Jewish heritage of Eastern Europe and Russia. of Beba Epstein, is currently being tested. Through Please come for a visit, sign up for a tour, or catch us the art of storytelling the museum will provide the online on our YouTube channel (@YIVOInstitute). historical context for the archive’s vast array of original documents, books, and other artifacts, with some materials being translated to English for the first time. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer Divided allegiance Citation for published version: Joseph, J 2016, 'Divided allegiance: Martinet’s preface to Weinreich’s Languages in Contact (1953)', Historiographia Linguistica, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 343-362. https://doi.org/10.1075/hl.43.3.04jos Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1075/hl.43.3.04jos Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Historiographia Linguistica General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 22. Feb. 2020 HL 43.3 (2016): Article Divided Allegiance Martinet’s preface to Weinreich’s Languages in Contact (1953)* John E. Joseph University of Edinburgh 1. Introduction The publication in 1953 of Languages in Contact: Findings and problems by Uri- el Weinreich (1926–1967) was a signal event in the study of multilingualism, individ- ual as well as societal. The initial print run sold out by 1963, after which the book caught fire, and a further printing was needed every year or two. -

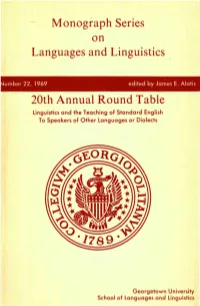

Monograph Series on Languages and Linguistics 20Th Annual Round Table

Monograph Series on Languages and Linguistics lumber 22, 1969 edited by James E. Alatis 20th Annual Round Table Linguistics and the Teaching of Standard English To Speakers of Other Languages or Dialects Georgetown University School of Languages and Linguistics REPORT OF THE TWENTIETH ANNUAL ROUND TABLE MEETING ON LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE STUDIES JAMES E. ALATIS EDITOR GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY PRESS Washington, D.C. 20007 © Copyright 1970 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY PRESS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 58-31607 Lithographed in U.S.A. by EDWARDS BROTHERS, INC. Ann Arbor, Michigan CONTENTS Introduction vii WELCOMING REMARKS Reverend Frank Fadner, S. J. Regent, School of Languages and Linguistics xi Dean Robert Lado Dean, School of Languages and Linguistics xiii FIRST SESSION Theoretical Linguistics and Its Implications for Teaching SESOLD Chairman: Charles W. Kreidler, Georgetown University William Labov The Logic of Nonstandard English 1 Raven I. McDavid, Jr. A Theory of Dialect 45 Rudolph C. Troike Receptive Competence, Productive Competence, and Performance 63 Charles T. Scott Transformational Theory and English as a Second Language/Dialect 75 David W. Reed Linguistics and Literacy 93 FIRST LUNCHEON ADDRESS Harold B. Allen The Basic Ingredient 105 iv / CONTENTS SECOND SESSION Applied Linguistics and the Teaching of SESOLD: Materials, Methods, and Techniques Chairman: David P. Harris, Georgetown University Peter S. Rosenbaum Language Instruction and the Schools 111 Betty W. Robinett Teacher Training for English as a Second Dialect and English as a Second Language: The Same or Different? 121 Eugene J. Briere Testing ESL Skills among American Indian Children 133 Bernard Spolsky Linguistics and Language Pedagogy—Applications or Implications ? 143 THIRD SESSION Sociolinguistics: Sociocultural Factors in Teaching SESOLD Chairman: A. -

Jewish Communal Services: Programs and Finances

Jewish Communal Services: Programs and Finances .ANY TYPES of Jewish communal services are provided under organized Jewish sponsorship. Some needs of Jews (and non-Jews) are ex- clusively individual or governmental responsibilities, but a wide variety of services is considered to be the responsibility of the total Jewish community. While the aim is to serve Jewish community needs, some services may also be made available to the general community. Most services are provided at the geographic point of need, but their financing may be secured from a wider area, nationally or internationally. This report deals with the financial contribution of American Jewry to do- mestic and global services and, to a lesser extent, with aid given by Jews in other parts of the free world. Geographic classification of services (i.e. local, national, overseas) is based on areas of program operation. A more fundamental classification would be in terms of type of services provided or needs met, regardless of geography. On this basis, Jewish com- munal services would encompass: • Economic aid, mainly overseas: largely a function of government in the United States. • Migration aid—a global function, involving movement between coun- tries, mainly to Israel, but also to the United States and other areas in sub- stantial numbers at particular periods. • Absorption and resettlement of migrants—also a global function, in- volving economic aid, housing, job placement or retraining, and social adjustment. The complexity of the task is related to the size of movement, the background of migrants, the economic and social viability or absorptive potential of the communities in which resettlement takes place, and the avail- ability of resources and structures for absorption in the host communities. -

A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall [email protected]

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons HON499 projects Honors Program Fall 11-29-2017 A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Other Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Wall, Ryan, "A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect" (2017). HON499 projects. 12. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects/12 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in HON499 projects by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall Honors 499 Fall 2017 RUNNING HEAD: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF THE PHILADELPHIA DIALECT 2 Introduction A walk down Market Street in Philadelphia is a truly immersive experience. It’s a sensory overload: a barrage of smells, sounds, and sights that greet any visitor in a truly Philadelphian way. It’s loud, proud, and in-your-face. Philadelphians aren’t known for being a quiet people—a trip to an Eagles game will quickly confirm that. The city has come to be defined by a multitude of iconic symbols, from the humble cheesesteak to the dignified Liberty Bell. But while “The City of Brotherly Love” evokes hundreds of associations, one is frequently overlooked: the Philadelphia Dialect. -

Editors Rena Torres Cacoullos Pennsylvania State University William Labov University of Pennsylvania

09543945_25-1.qxd 3/14/13 12:07 PM Page 1 VOLUME 25, NUMBER 1 2013 Volume 25 Number 1 2013 CONTENTS ANTHONY JULIUS NARO AND MARIA MARTA PEREIRA SCHERRE Remodeling the age variable: Number concord in Brazilian Portuguese 1 LAUREL MACKENZIE Variation in English auxiliary realization: A new take on contraction 17 YOUSEF AL-ROJAIE Regional dialect leveling in Najdi Arabic: The case of the deaffrication 25,Volume Number 1 2013 1–118 Pages of [k] in the Qas.¯mıı ¯ dialect 43 DANIEL WIECHMANN AND ARNE LOHMANN Domain minimization and beyond: Modeling prepositional phrase ordering 65 JOHN C. PAOLILLO Individual effects in variation analysis: Model, software, and research design 89 Editors Rena Torres Cacoullos Pennsylvania State University William Labov University of Pennsylvania Instructions for Contributors on inside back cover Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/lvc Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.126, on 25 Sep 2021 at 17:52:18, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394513000021 09543945_25-1.qxd 3/14/13 12:07 PM Page 2 notes for contributors Language Variation and Change publishes original publication, and, where relevant, the page(s) referred to: research reports that are based on data of language (Vincent, 1982:90–91). If the author’s name is part of the EDITORS production, either oral or written, from contemporary text, the following form should be used: “Vincent (1982) RENA TORRES CACOULLOS WILLIAM LABOV or historical sources. -

A Jiddis Nyelv Szerkezete

BEVEZETÉS A JIDDIS NYELVBE ÉS KULTÚRÁBA 1 HB-N-452, AS/N-282/b, VKN-007.07 2005/2006. őszi félév Komoróczy Szonja Ráhel A jiddis nyelv szerkezete A jiddis nyelv meghatározása • zsidó nyelv • európai nyelv • germán nyelv • devokabularizált szláv nyelv • elrontott német, jüdisch-Deutsch, keveréknyelv, zsargon; • jiddisista szemlélet; • fúzionált nyelv A jiddis nyelv összetétele • szókincs, nyelvtan • hangkészlet • hangsúly Fusion language Max Weinreich: fusion language vs. mixed language Alapnyelvek (Stock Languages) Determináns nyelvek (Determinant Languages) Komponensek (Component Languages) A fúzió jellegzetességei • nem véletlenszerű • inter-komponens produktivitás • intra-komponens produktivitás • szemantikai játéktér több komponenssel • többszörös szóátvétel azonos alapnyelvből (más determináns) • komponens tudatosság • komponens, ill. alapnyelv közötti különbség felismerése A loshn koydesh komponens teljes héber (whole Hebrew) – a determináns nyelv beolvadt héber (merged Hebrew) – a sémi eredetű komponens. • Szövegelmélet (Text Theory) – Max Weinreich • Folyamatos átadás elmélete (Continual Transmission Theory) – Dovid Katz A laaz komponens BEVEZETÉS A JIDDIS NYELVBE ÉS KULTÚRÁBA 2 HB-N-452, AS/N-282/b, VKN-007.07 2005/2006. őszi félév Komoróczy Szonja Ráhel A jiddis nyelv dialektológiája A jiddis dialektológia kezdetei: • Maharil (Yakov ben Moshe haLevi Moellin) (1360-1427) a szokásokról és nyelvi (bney estraykh (bney khes בני עסטרײַך .bney rinus (bney hes), ill ,בני רינוס ;standardről • Isserlin (Yisroel ben Pesakhya) (1390-1460) • Yosselin (Yosef ben Moshe) (1423-1490) dialektus és ethnográfia • Johannes Buxtorf • Carl Wilheim Friedrich: Unterricht in der Judensprache und Schrift, zum Gebrauch für Gelehrte und Ungelehrte (1784), leírja és elemzi a dialektusokat. A modern jiddis dialektológia története: • Germanisták: Lazar Saineanu, Alfred Landau • Jiddisisták, Noyakh Prilutski (1882-1941) • YIVO, Berlin / Vilnius (1925-1939) – dialektológia, ethnográfia, folklór. -

William Labov Unendangered Dialect, Endangered People

TRAA 1066 Dispatch: 27.1.10 Journal: TRAA CE: Lalitha Rao Journal Name Manuscript No. B Author Received: No. of pages: 14 Op: Chris/TMS 1 WILLIAM LABOV 51 2 52 3 UNENDANGERED DIALECT,ENDANGERED PEOPLE:THE CASE 53 4 54 5 OF AFRICAN AMERICAN VERNACULAR ENGLISH 55 6 56 7 57 8 58 9 African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is not The primary condition for such divergence is resi- 59 10 an endangered language variety; on the contrary, it is dential segregation. 60 11 continuing to develop, as all languages, and to diverge Residential segregation, combined with increasing 61 12 from other varieties. The primary correlates of such poverty, has led to a deterioration of many 62 13 divergence are residential segregation and poverty, features of social life in the inner cities. 63 14 which are part of a developing transgenrational cycle In these conditions, a majority of children in inner 64 15 that includes also crime, shorter life spans, and low city schools are failing to learn to read, with a 65 16 educational achievement. The most immediate challenge developing cycle of poverty, crime, and shorter life 66 17 is creating more effective educational programs on a span. 67 18 larger scale. In confronting residential segregation, we Reduced residential segregation will lead to great- 68 19 must be aware that its reduction will lead to greater er contact between speakers of AAVE and 69 20 contact between speakers of AAVE and speakers of speakers of other dialects. 70 21 other dialects. Recent research implies that, if residen- If, at some future date, the social conditions that 71 22 tial integration increases significantly, AAVE as favor the divergence of AAVE are altered, then 72 23 a whole may be in danger of losing its distinctiveness AAVE in its present form may become an endan- 73 24 as a linguistic resource. -

Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Cantonese Sociolinguistic Patterns: Correlating Social Characteristics of Speakers with Phonological Variables in Hong Kong Cantonese Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1sn2f75h Author Bauer, Robert Publication Date 1982 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Cantonese Sociolinguistic Patterns: Correlating Social Characteristics of Speakers with Phonological Variables in Hong Kong Cantonese By Robert Stuart Bauer A.B. (Southwest Missouri State College) 1969 M.A. (University of California) 1975 C.Phil. (University of California) 1979 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OE PHILOSOPHY in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Approved t-—\ Chairman , x? Date i J, 4 (A DOCTORAL DEGREE COiU JUNE 19, 1982 i ACKNOWLEDGMENT My first year of research in Hong Kong during which time I retooled my Cantonese, planned the design of this research project, and prepared the interview questions was supported by a U.S. Department of State Teaching Fellowship at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In my second year in Hong Kong, a U.S. Department of Education Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Fellowship eliminated financial anxiety and made it possible to concentrate exclu sively on conducting the linguistic interviews and other phases of the research. It was in this second year that I lived on Lamma Island, a welcome refuge from the hustle and crush of Hong Kong and the closest thing to a pastoral paradise one could hope for in a place like Hong Kong. I now look back on that year as the happiest time in my life. -

Dovid Katz Phd Thesis University College London Submitted October' 1982

Dovid Katz PhD Thesis University College London Submitted October' 1982 Explorations in the History of the Semitic Component in Yiddish Vol. 1 I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I entered the field of Yiddish Linguistics during the years I was privileged to study wider Professor Mikhl Herzog at Columbia University. I am profoundly grateful to Professor Herzog f or his continuous help, guidance and inspiration, during both my undergraduate enrolment at Columbia University in New York arid my postgraduate residence at University College London. I would ask Professor Herzog to regard this thesis as a provisional progress report and outline for further research. I have been fortunate to benefit from the intellectual environment of University College London while preparing the work reported In the thesis, and. most especially from the dedicated help, expert criticism and warm hospitality of my three supervisors, Professor Chimen Abrainsky and Professor Raphael Loewe of the Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and. Dr. Richard A. Hudson of the Department of Phonetics and. Linguistics. Professor Loewe and Dr. Hudson generously gave of their time to spend many hours discussing with me the issues and problems of the thesis. They both read the entire manuscript and made many valuable suggestions f or Improvement. Most have been incorporated into the text as submitted to the University of London. I hope to elaborate upon the remainder ii in future work. Professor Abramsky provided superb guidance in the fields of literary history and bibliography and generously made available to me numerous rare volumes from his magnificent private library. Needless to say, full responsibility for the proposals herein and. -

African American Vernacular English Erik R

Language and Linguistics Compass 1/5 (2007): 450–475, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00029.x PhonologicalErikBlackwellOxford,LNCOLanguage1749-818x©Journal02910.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00029.xAugust0450???475???Original 2007 Thomas 2007 UKThecompilationArticles Publishing and Authorand Linguistic Phonetic © Ltd 2007 CharacteristicsCompass Blackwell Publishing of AAVE Ltd Phonological and Phonetic Characteristics of African American Vernacular English Erik R. Thomas* North Carolina State University Abstract The numerous controversies surrounding African American Vernacular English can be illuminated by data from phonological and phonetic variables. However, what is known about different variables varies greatly, with consonantal variables receiving the most scholarly attention, followed by vowel quality, prosody, and finally voice quality. Variables within each domain are discussed here and what has been learned about their realizations in African American speech is compiled. The degree of variation of each variable within African American speech is also summarized when it is known. Areas for which more work is needed are noted. Introduction Much of the past discussion of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) has dealt with morphological and syntactic variables. Such features as the invariant be (We be cold all the time), copula deletion (We cold right now), third-person singular -s absence (He think he look cool) and ain’t in place of didn’t (He ain’t do it) are well known among sociolinguists as hallmarks of AAVE (e.g. Fasold 1981). Nevertheless, phonological and phonetic variables characterize AAVE just as much as morphosyntactic ones, even though consonantal variables are the only pronunciation variables in AAVE that have attracted sustained attention. AAVE has been at the center of a series of controversies, all of which are enlightened by evidence from phonology and phonetics. -

Max Weinreich at UCLA in 1948

UCLA’s First Yiddish Moment: Max Weinreich at UCLA in 1948 Mark L. Smith* (Photographs appear on the last page) In the summer of 1948, Max Weinreich brought the world of Yiddish culture to UCLA. He was the leading figure in Yiddish scholarship in the postwar period, and the two courses he taught at UCLA appear to be first instance of Jewish Studies at the university. His courses gave new direction to his students’ careers and to the academic study of Yiddish. From these courses there emerged six prominent Yiddish scholars (and at least three marriages) and evidence that Yiddish culture was a subject suitable for American research universities. Earlier that year, a strategically placed cartoon had appeared in a Yiddish-language magazine for youth published in New York. In it, a young man announces to his father, “Dad, I’ve enrolled in a Yiddish class at college.” His well-dressed and prosperous-looking father replies, in English, “What!? After I’ve worked for twenty years to make an American of you!?”1 The founding editor of the magazine, Yugntruf (Call to Youth), was Weinreich’s son, Uriel, himself to become the preeminent Yiddish linguist of his generation. The cartoon celebrates the elder Weinreich’s inauguration of Yiddish classes at New York’s City College in the fall of 1947, and it anticipates his visit to California the following summer. * Ph.D. candidate, Jewish History, UCLA. An abbreviated version of this paper was presented at the conference “Max Weinreich and America,” convened by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City, December 4, 2011.