Charles Wuorinen's Reliquary for Stravinsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Msm Camerata Nova

Saturday, March 6, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM CAMERATA NOVA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM JAMES LEE III A Narrow Pathway Traveled from Night Visions of Kippur (b. 1975) CHARLES WUORINEN New York Notes (1938–2020) (Fast) (Slow) HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS Chôros No. 7 (1887–1959) MAURICE RAVEL Introduction et Allegro (1875–1937) CAMERATA NOVA VIOLIN 1 VIOLA OBOE SAXOPHONE HARP Youjin Choi Sara Dudley Aaron Zhongyang Ling Minyoung Kwon New York, New York New York, New York Haettenschwiller Beijing, China Seoul, South Korea Baltimore, Maryland VIOLIN 2 CELLO PERCUSSION PIANO Ally Cho Rei Otake CLARINET Arthur Seth Schultheis Melbourne, Australia Tokyo, Japan Ki-Deok Park Dhuique-Mayer Baltimore, Maryland Chicago, Illinois Champigny-Sur-Marne, France FLUTE Tarun Bellur Marcos Ruiz BASSOON Plano, Texas Miami, Florida Matthew Pauls Simi Valley, California ABOUT THE ARTISTS George Manahan, Conductor George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. -

Concert Programdownload Pdf(349

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Stockhausen's Mantra For Two Pianos Eric Huebner and Steven Beck, pianos Sound and electronic interface design: Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Sound projection: Chris Jacobs and Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Saturday, October 14, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Mantra (1970) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) Program Note by Katherine Chi To say it as simply as possible, Mantra, as it stands, is a miniature of the way a galaxy is composed. When I was composing the work, I had no accessory feelings or thoughts; I knew only that I had to fulfill the mantra. And it demanded itself, it just started blossoming. As it was being constructed through me, I somehow felt that it must be a very true picture of the way the cosmos is constructed, I’ve never worked on a piece before in which I was so sure that every note I was putting down was right. And this was due to the integral systemization - the combination of the scalar idea with the idea of deriving everything from the One. It shines very strongly. - Karlheinz Stockhausen Mantra is a seminal piece of the twentieth century, a pivotal work both in the context of Stockhausen’s compositional development and a tour de force contribution to the canon of music for two pianos. It was written in 1970 in two stages: the formal skeleton was conceived in Osaka, Japan (May 1 – June 20, 1970) and the remaining work was completed in Kürten, Germany (July 10 – August 18, 1970). -

Igor Strav Thursday 21 & Sunday 24 September

Thursday 21 & Sunday 24 September Igor Stravinsky in Profile 1882–1971 / profile by Paul Griffiths LSO SEASON CONCERT hird in a family of four sons, Before that was completed, a ballet based In 1939, soon after the deaths of his wife STRAVINSKY INTRODUCTION from Paul Griffiths he had a comfortable upbringing in on 18th-century music, Pulcinella (1919–20), and mother, he sailed to New York with St Petersburg, where his father opened the door to a whole neoclassical period, Vera, whom he married, and with whom he Stravinsky The Firebird (original ballet) Writing back to a Russian friend in 1912, was a Principal Bass at the Mariinsky Theatre. which was to last three decades and more. settled in Los Angeles. Following his opera Interval – 20 minutes as he worked in Switzerland on The Rite In 1902 he started lessons with Rimsky- He also began spending much of his time The Rake’s Progress (1947–51) he began to Stravinsky Petrushka (1947 version) of Spring, Stravinsky remarked: ‘It is as Korsakov, but he was a slow developer, in Paris and on tour with his mistress Vera interest himself in Schoenberg and Webern, Interval – 20 minutes if twenty and not two years had passed and hardly a safe bet when Diaghilev Sudeikina, while his wife, mother and children and within three years had worked out a Stravinsky The Rite of Spring since The Firebird was composed’. commissioned The Firebird. The success lived elsewhere in France. Up to the end of new serial style. Sacred works became more STRA This evening we have the rare opportunity of that work encouraged him to remain the 1920s, his big works were nearly all for and more important, to end with Requiem Sir Simon Rattle conductor to relive those packed and extraordinary in western Europe, writing scores almost the theatre (including the nine he wrote for Canticles (1965–66), which was performed two years in two hours, following the annually for Diaghilev. -

Wuorinen Printable Program

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Celebrating Charles Wuorinen at 80 featuring Ensemble SIGNAL Brad Lubman, conductor Tuesday, April 24, 2018 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Charles Wuorinen (b. 1938) iRidule Jacqueline Leclair, oboe soloist Spin 5 Olivia De Prato, violin soloist Intermission Megalith Eric Huebner, piano soloist PERSONNEL Ensemble Signal Brad Lubman, Music Director Paul Coleman, Sound Director Olivia De Prato, Violin Lauren Radnofsky, Cello Ken Thomson, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet Adrián Sandí, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet David Friend, Piano 1 Oliver Hagen, Piano 2 Karl Larson, Piano 3 Georgia Mills, Piano 4 Matt Evans, Vibraphone, Piano Carson Moody, Marimba 1 Bill Solomon, Marimba 2 Amy Garapic, Marimba 3 Brad Lubman, Marimba Sarah Brailey, Voice 1 Mellissa Hughes, Voice 2 Kirsten Sollek, Voice 4 Charles Wuorinen In 1970 Wuorinen became the youngest composer at that time to win the Pulitzer Prize (for the electronic work Time's Encomium). The Pulitzer and the MacArthur Fellowship are just two among many awards, fellowships and other honors to have come his way. Wuorinen has written more than 260 compositions to date. His most recent works include Sudden Changes for Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, Exsultet (Praeconium Paschale) for Francisco Núñez and the Young People's Chorus of New York, a String Trio for the Goeyvaerts String Trio, and a duo for viola and percussion, Xenolith, for Lois Martin and Michael Truesdell. The premiere of of his opera on Annie Proulx's Brokeback Mountain was was a major cultural event worldwide. -

Interview with Charles Wuorinen Международный Отдел

Международный отдел • International Division ISSN 1997-0854 (Print), 2587-6341 (Online) DOI: 10.17674/1997-0854.2019.4.046-056 Interview with Charles Wuorinen Dear readers of the journal “Problemy muzykal’noj nauki / Music Scholarship”! he editorial board of the journal with composer and performer Harvey T“Problemy muzykalnoj nauki / Music Solberger, he was one of the leaders of the Scholarship” is happy to concert series, the Group present an interview with the for Contemporary Music, famous American composer devoted to performance Charles Wuorinen. At the of works by contemporary present time Wuorinen is the composers. In the 1970s most well-known composer Wuorinen wrote an orchestral of twelve-tone music in the composition A Reliquary for USA. He was born in New Igor Stravinsky, in which he York City in 1938, studied incorporated the last musical at Columbia University in sketches of the great master. New York, and subsequently Wuorinen is the author of taught at many universities Charles Wuorinen. a book on serial music, and conservatories in the Photo by Nina Roberts titled Simple Composition, USA, including Columbia which he characterizes as a University, Manhattan School of Music (New manual for composers, meant to teach them York), Princeton University and Rutgers how to compose music, and not a music University (New Jersey), New England theory book analyzing already composed Conservatory (Massachussetts), etc. In 1970 works. Wuorinen’s music is well-known he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his in the USA and in the countries of Western electronic composition Time’s Encomium, Europe, where there are frequent premiere composed with the use of the RCA Synthesizer performances of his new compositions, at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music among which it becomes proper to name Center. -

Brentano String Quartet

“Passionate, uninhibited, and spellbinding” —London Independent Brentano String Quartet Saturday, October 17, 2015 Riverside Recital Hall Hancher University of Iowa A collaboration with the University of Iowa String Quartet Residency Program with further support from the Ida Cordelia Beam Distinguished Visiting Professor Program. THE PROGRAM BRENTANO STRING QUARTET Mark Steinberg violin Serena Canin violin Misha Amory viola Nina Lee cello Selections from The Art of the Fugue Johann Sebastian Bach Quartet No. 3, Op. 94 Benjamin Britten Duets: With moderate movement Ostinato: Very fast Solo: Very calm Burlesque: Fast - con fuoco Recitative and Passacaglia (La Serenissima): Slow Intermission Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 67 Johannes Brahms Vivace Andante Agitato (Allegretto non troppo) Poco Allegretto con variazioni The Brentano String Quartet appears by arrangement with David Rowe Artists www.davidroweartists.com. The Brentano String Quartet record for AEON (distributed by Allegro Media Group). www.brentanoquartet.com 2 THE ARTISTS Since its inception in 1992, the Brentano String Quartet has appeared throughout the world to popular and critical acclaim. “Passionate, uninhibited and spellbinding,” raves the London Independent; the New York Times extols its “luxuriously warm sound [and] yearning lyricism.” In 2014, the Brentano Quartet succeeded the Tokyo Quartet as Artists in Residence at Yale University, departing from their fourteen-year residency at Princeton University. The quartet also currently serves as the collaborative ensemble for the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The quartet has performed in the world’s most prestigious venues, including Carnegie Hall and Alice Tully Hall in New York; the Library of Congress in Washington; the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam; the Konzerthaus in Vienna; Suntory Hall in Tokyo; and the Sydney Opera House. -

Music Resources – Library Update – March, 2014

Music Resources – Library Update – March, 2014 This music collection’s update is dedicated to the great Canadian music personality Charles Thomas “Stompin’ Tom” Connors who died one year ago this month. “Stompin’ Tom” is widely known for his songs Bud the Spud and The Hockey Song…the latter frequently performed at games throughout the NHL. Within the music business, Tom is greatly admired for his unswerving support for Canadian musicians – including promoting their work through the record labels he founded. Tom, this one’s for you! UBC Library’s music collection receives new materials regularly. The following are highlights from recent acquisitions. A quick way to make your way through the lists below is to use the ‘Control F’ function on your keyboard and search by composer or instrument of interest. Otherwise, the materials are grouped by books, e-books and scores. Call numbers link to catalogue records for more information. “Click here” links to text or performance. Books Britten: Essays, Letters and Opera Guides Keller, Hans, Christopher Wintle, A. M. Garnham, Ines Schlenker, Kate Hopkins, Milein Cosman, and Cosman Keller Art and Music Trust. 2013. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Cosman Keller Art and Music Trust in association with Plumbago Books. Call Number: ML410 B853 K455 2013 Location: I.K. BARBER LIBRARY stacks Mapping Canada's Music: Selected Writings of Helmut Kallmann Kallmann, Helmut, John Beckwith, and Robin Elliott. 2013. Waterloo, Ont: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Call Number: ML205 K35 2013 Location: I.K. BARBER LIBRARY stacks Fandom, Authenticity, and Opera: Mad Act n tt S n in in- -Si i Fishzon, Anna. -

Han Chen / Piano

HAN CHEN / PIANO Hailed by the New York Times as a pianist with "a graceful touch... rhythmic precision... hypnotic charm” and "sure, subtle touch," Han Chen is a distinctive artist whose credentials at a young age already include important prizes in competitions of traditional music as well as increasing respect in the avant- garde. Mr. Chen’s debut CD with Naxos Records, which consists of all-Liszt operatic transcriptions, was released in January 2016 as the first prize winner of the 6th China International Piano Competition. Gramophone complimented Mr. Chen’s “brilliant performance” in the CD as “impressively commanding and authoritative.” The website Classics Today also praised for his “assured, elegant and totally effortless technique” by scoring 10 out of 10 in both artistic quality and sound quality. International Piano magazine (UK) described Mr. Chen’s performance in the competition as “[Chen] displayed extraordinary strength, talent and flair.” His performances in the 15th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, the 15th Arthur Rubinstein Piano Competition and the 2018 Honens International Piano Competition were also highly acclaimed. As a soloist, Mr. Chen has appeared with many orchestras, including the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra (under Maestro Vladimir Ashkenazy), Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, China Symphony Orchestra, Macao Orchestra, Juilliard Orchestra, National Taiwan Symphony Orchestra, Xiamen National Orchestra, Lexington Philharmonic Orchestra, Sendai Philharmonic Orchestra, Aspen Music Festival Brass Ensemble and Shanghai Conservatory Middle School Orchestra. Being an advocate for modern music, Mr. Chen actively performs music from the 20th and the 21st century. As a member of the New York-based contemporary music group Ensemble Échappé, he worked with composers such as Tonia Ko, Kevin Puts, Sean Shepherd and Nina Young. -

Charles Wuorinen

NWCR744 Charles Wuorinen 3. I ........................................................... (7:42) 4. II ........................................................... (6:36) 5. III ........................................................... (4:42) David Braynard, tuba solo; The Group for Contemporary Music: Patricia Spencer, Harvey Sollberger, Sophie Sollberger, Karl Kraber, flutes; Josef Marx, Susan Barrett, oboes; Donald MacCourt, Leonard Hindell, bassoons; David Jolley, Edward Birdwell, Ronald Sell, Barry Benjamin, horns; Raymond DesRoches, percussion; Charles Wuorinen, conductor 6. Piano Concerto (1966) ......................................... (19:47) Charles Wuorinen, piano; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; James Dixon, conductor 7. Chamber Concerto for Flute and Ten Players (1964) ........................................ (14:48) Harvey Sollberger, flute; The Group for Contemporary Music: Stanley Silverman, guitar; Susan Jolles, harp; Cheryl Seltzer, harpsichord; Joan Tower, celeste; Robert Miller, piano; Raymond DesRoches, John Bergamo, Richard Fitz, George Boberg, percussion; Two Part Symphony (1977-78) ................................ (23:30) Kenneth Fricker, contrabass; Charles Wuorinen, 1. I ...........................................................(12:27) conductor 2. II ...........................................................(11:03) Total playing time: 77:27 American Composers Orchestra; Dennis Russell Davies, conductor; Chamber Concerto for Tuba Ê 1979, 1983, 1997 © 1997 Composers Recordings, Inc. with 12 Winds and 12 Drums -

Biographies Creative Team George Manahan Eve Summer Conductor Stage Director

Biographies Creative Team George Manahan Eve Summer Conductor Stage Director George Manahan has had an esteemed career Eve Summer is a director, producer, and embracing opera and the concert stage, from the choreographer whose recent directing credits traditional to the contemporary. He is the music include Trouble in Tahiti at the Glimmerglass director of the American Composers Orchestra Festival, The Pearl Fishers at Opera Tampa, The and Portland Opera, and previously served as Little Prince at Tulsa Opera, The Tales of Hoffmann music director of New York City Opera for at Opera Orlando, Xerxes for Connecticut Early fourteen seasons. He has appeared as guest Music Festival, Aïda and Lucia di Lammermoor conductor with the opera companies of Seattle, at Boheme Opera New Jersey, Suor Angelica in Santa Fe, San Francisco, Chicago, Opera Theatre concert with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, of St. Louis, Opera National du Paris and Teatro Così fan tutte for Connecticut Lyric Opera, de Communale de Bologna; as well as the Lucia di Lammermoor for Commonwealth National, New Jersey, Atlanta, San Francisco, Opera, Carmen for MassOpera, and the world Milwaukee, and Indianapolis symphonies and premiere of Larry Bell’s Holy Ghosts at the the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra. Berklee Performance Center. Dedicated to the music of our time, This season Ms. Summer also directs Mr. Manahan has led premieres of Tobias The Pirates of Penzance at Opera Saratoga, Picker’s Dolores Claiborne, Charles Wuorinen’s John Musto’s Later The Same Evening at Boston Haroun and the Sea of Stories, David Lang’s University, The Mikado at Opera Grand Rapids, Modern Painters, Hans Werner Henze’s The The Pearl Fishers at Opera in Williamsburg, English Cat, Terence Blanchard’s Champion, Bluebeard’s Castle at Mid-Ohio Opera, and the New York premiere of Richard Danielpour’s Il Tabarro and Gianni Schicchi at Yale Opera. -

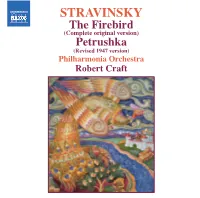

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye's À La Manière De Stravinsky Pour Trombone Et Piano

A COMPARISON OF RHYTHM, ARTICULATION, AND HARMONY IN JEAN- MICHEL DEFAYE’S À LA MANIÈRE DE STRAVINSKY POUR TROMBONE ET PIANO TO COM MON COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES OF IGOR STRAVINSKY Dustin Kyle Mullins, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Tony Baker, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Mullins, Dustin Kyle. A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye’s À la Manière de Stravinsky pour Trombone et Piano to Common Compositional Strategies of Igor Stravinsky. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2014, 45 pp., 2 tables, 27 examples, references, 28 titles. À la Manière de Stravinsky is one piece in a series of works composed by Jean- Michel Defaye that written emulating the compositional styles of significant composers of the past. This dissertation compares Defaye’s work to common compositional practices of Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971). There is currently limited study of Defaye’s set of À la Manière pieces and their imitative characteristics. The first section of this dissertation presents the significance of the project, current literature, and methods of examination. The next section provides critical information on Jean-Michel Defaye and Igor Stravinsky. The following three chapters contain a compositional comparison of À la Manière de Stravinsky to Stravinsky’s use of rhythm, articulation, and harmony. The final section draws a conclusion of the piece’s significance in the solo trombone repertoire.