SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cold War Cultures in Korea by Travis Workman

Cold War Cultures in Korea Instructor: Travis Workman Campuses: U of Minnesota, Ohio State U, and Pennsylvania State U Course website: http://coldwarculturesinkorea.com In this course we will analyze the Cold War (1945-1989) not only as an era in geopolitics, but also as a historical period marked by specific cultural and artistic forms. We focus on the Korean peninsula, looking closely at the literary and film cultures of both South Korea and North Korea. We discuss how the global conflict between U.S.- centered and Soviet-centered societies affected the politics, culture, and geography of Korea between 1945 and 1989, treating the division of Korea as an exemplary case extending from the origins of the Cold War to the present. We span the Cold War divide to compare the culture and politics of the South and the North through various cultural forms, including anti-communist and socialist realist films, biography and autobiography, fiction, and political discourse. We also discuss the legacy of the Cold War in contemporary culture and in the continued existence of two states on the Korean peninsula. The primary purpose is to be able to analyze post-1945 Korean cultures in both their locality and as significant aspects of the global Cold War era. Topics will include the politics of melodrama, cinema and the body, visualizing historical memory, culture under dictatorship, and issues of gender. TEXTS For Korean texts and films, the writer or director’s family name appears first. Please use the family name in your essays and check with me if you are unsure. -

L'énonciation Épistolaire Dans Les Cinémas Contemporains De Fiction

MONOGRÁFICO Área Abierta. Revista de comunicación audiovisual y publicitaria ISSN: 2530-7592 / ISSNe: 1578-8393 https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/arab.63968 L’énonciation épistolaire dans les cinémas contemporains de fiction en Asie : essai typologique Antoine Coppola1 Reçu : 07 mai 2019 / Accepté : 30 juin 2019 Résumé. En Asie, l’histoire socio-linguistique a parfois fait fleurir les énoncés épistolaires à l’écran et, parfois, les a fait flétrir. Les mélodrames ont développé les lettres-destin oralisés comme des charnières de la narration dramatique. Même un cinéma sous régime communiste comme celui de la Corée du Nord entretien ce modèle, mais en le détournant au profit de son épistolier et leader suprême. À partir des années 1990, des cinéastes comme Shunji Iwai ou Jeong Jae-eun ont écranisé les missives en leur attribuant un pouvoir de véridiction en conflit : social/persona. Wong Kar-wai a étendu l’énonciation épistolaire à l’ensemble de la structure narrative des voix off de ses films comme autant d’intériorités mémorielles. Enfin, la transition vers les espaces de communication numériques et virtuels, a amené des cinéastes comme Hideo Nakata ou Jia Zhangke à souligner la distance hantologique, spectrale dans le sens de Derrida ; distance liée au pouvoir de grands communicateurs invisibles devenus des tiers incontournables au cœur de tous les échanges. Mots-clefs : hantologie ; intériorité ; véridiction ; spectacle ; inter-subjectivité ; persona [es] Le enunciación epistolar en los cines de ficción contemporáneos de Asia: ensayo tipológico Resumen. La historia sociolingüística de Asia en unas ocasiones ha hecho florecer los enunciados epis- tolares en la pantalla y en otras los ha hecho marchitar. -

December 13, 1977 Report on the Official Friendship Visit to the DPRK by the Party and State Delegation of the GDR, Led by Comrade Erich Honecker

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified December 13, 1977 Report on the Official Friendship Visit to the DPRK by the Party and State Delegation of the GDR, led by Comrade Erich Honecker Citation: “Report on the Official Friendship Visit to the DPRK by the Party and State Delegation of the GDR, led by Comrade Erich Honecker,” December 13, 1977, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, SAPMO-BA, DY 30, J IV 2/2A/2123. Translated by Grace Leonard. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112308 Summary: Report on the official visit to the DPRK of a GDR delegation led by Erich Honecker. Included are the summary of the visit and the text of the Agreement on Developing Economic and Scientific/Technical Cooperation. Original Language: German Contents: English Translation CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF THE SOCIALIST UNITY PARTY -- Internal Party Archives -- From the files of: Politburo Memorandum No. 48 13 December 1977 DY30/ Sign.: J IV 2/2 A -- 2123 Report on the official friendship visit to the Democratic People's Republic of Korea by the Party and state delegation of the German Democratic Republic, led by Comrade Erich Honecker, Secretary General of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany and Chairman of the State Council of the German Democratic Republic, from 8 to 11 December 1977. ________________________________________________________________________ At the invitation of the Central Committee of the Korean Workers Party and the Council of Ministers of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, a Party and state delegation from the German Democratic Republic, led by Comrade Erich Honecker, Secretary General of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany and Chairman of the State Council of the German Democratic Republic, made an official friendship visit to the DPRK from 8 to 11 December 1977. -

Winstanley-Chesters, BAKS Papers 16

BAKS Papers, Volume 16 The British Association For Korean Studies, 2015 North Korean Pomiculture 1958–1967: Pragmatism And Revolution Robert Winstanley-Chesters Post-Doctoral Fellow of the University of Cambridge (Beyond the Korean War), Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Leeds Robert Winstanley-Chesters is a Post Doctoral Fellow of the Beyond the Korean War Project (University of Cambridge), Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Leeds' School of Geography, and Director of Research at SinoNK.com. His doctoral thesis was published as Environment, Politics and Ideology in North Korea: Landscape as Political Project (Lexington Press, 2014). Robert’s second monograph, New Goddesses of Mt Paektu: Gender, Violence, Myth and Transformation in Korean Landscapes, has been accepted for publication in 2016 by Rowman and Littlefield (Lexington Press). Robert is currently researching Pyongyang’s leisure landscapes, historical geographies of Korean forestry, colonial mineralogical inheritances on the peninsula and animal/creaturely geographies of North Korea. Abstract Building on past analysis by its author of North Korea’s history of developmental approach and environmental engagement, this paper encounters the field of pomiculture (or orchard development and apple farming) in the light of another key text authored by Kim Il-sung, 1963’s “Let Us Make Better Use of Mountains and Rivers.” At this time North Korea had left the tasks of immediate agricultural and industrial reconstruction following the Korean War (1950–1953) behind and was engaged in an intense period of political and ideological triangulation with the great powers of the Communist/Socialist bloc. With relations between the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union in flux and Chairman Mao’s development and articulation of the “Great Leap Forward,” North Korea was caught in difficult ideological, developmental and diplomatic crosswinds. -

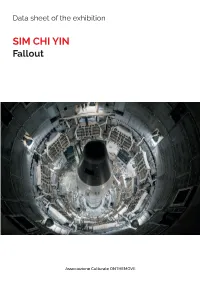

SIM CHI YIN Fallout

Data sheet of the exhibition SIM CHI YIN Fallout Associazione Culturale ONTHEMOVE DATA SHEET OF THE EXHIBITION | Fallout - Sim Chi Yin Fallout Sim Chi Yin Produced by Associazione culturale ONTHEMOVE in occasion of the Internation Photography Festival Cortona On The Move 2018 Curated by Arianna Rinaldo For information Antonio Carloni Director [email protected] +39 3286438076 Associazione culturale ONTHEMOVE | Località Vallone, 39/A/4 - Cortona, 52044 (AR) DATA SHEET OF THE EXHIBITION | Fallout - Sim Chi Yin Title Fallout Photographer Sim Chi Yin Curated by* Arianna Rinaldo Type of prints and mounting 17 color prints mounted on dilite Size of prints 11 prints 80 x 120 cm 5 prints 105 x 157 1 prints 105 x 144 cm Frames No frames. Prints are mounted on dilite (similar to dibond). Slider spacers in the back to be hung. Linear development 23 linear mt minimum (spaces not included) Video “Most people were silent”, 2017 Two-channel video installation with sound, 3:40 Set up annotations Text material must be printed at the expense of the hosting organization. We provide introduction text, biography and captions both in italian and english. *any changes to the selection or layout of the exhibition must be consulted with the curator Associazione culturale ONTHEMOVE | Località Vallone, 39/A/4 - Cortona, 52044 (AR) DATA SHEET OF THE EXHIBITION | Fallout - Sim Chi Yin FALLOUT In the pitch darkness, a single light reflected over the shallow waters of the Tumen river. All that was visible on the far shore was a pair of giant portraits: of North Korean founder Kim Il-sung and his son and successor Kim Jong-il. -

STATEMENT UPR Pre-Session 33 on the Democratic People's Republic

STATEMENT UPR Pre-Session 33 on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) Geneva, April 5, 2019 Delivered by: The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK) 1- Presentation of the Organization HRNK is the leading U.S.-based bipartisan, non-governmental organization (NGO) in the field of DPRK human rights research and advocacy. Our mission is to focus international attention on human rights abuses in the DPRK and advocate for an improvement in the lives of 25 million DPRK citizens. Since its establishment in 2001, HRNK has played an intellectual leadership role in DPRK human rights issues by publishing over thirty-five major reports. HRNK was granted UN consultative status on April 17, 2018 by the 54-member UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). On October 4, 2018, HRNK submitted our findings to the UPR of the DPRK. Based on our research, the following trends have defined the human rights situation in the DPRK over the past seven years: an intensive crackdown on attempted escape from the country leading to a higher number of prisoners in detention; a closure of prison camps near the border with China while camps inland were expanded; satellite imagery analysis revealing secure perimeters inside these detention facilities with watch towers seemingly located to provide overlapping fields of fire to prevent escapes; a disproportionate repression of women (800 out of 1000 women at Camp No. 12 were forcibly repatriated); and an aggressive purge of senior officials. 2- National consultation for the drafting of the national report Although HRNK would welcome consultation and in-country access to assess the human rights situation, the DPRK government displays a consistently antagonistic attitude towards our organization. -

Movies in Nk.Key

Making movies in North Korea eric Lafforgue Kim Jong Il was a huge fan of cinema and so the people of North Korea have become avid moviegoers. The deceased Dear Leader has a certain respect for this medium, allegedly calling it the “most powerful for educating the masses”. He went as far as to write an essay called “Theory of Cinematic Art” in which he explains that “it is cinema's duty to turn people into true communists”. For him, film was “a means of eradicating capitalist elements”. It is in fact an effective means of diffusing propaganda, especially towards the youth. That is why there is a state-run movie studio in Pyongyang. Kim Jong Il was said to have thousands of films in his personal library and to have 7 theaters built exclusively for him in Pyongyang. Apart from the main studio (Korean Film Studio), other studios have been built in the periphery of the capital. Kim Jong Il apparently shot a movie about the founder of North Korea, his father Kim Il-Sung, and proclaimed himself a “genius of cinema”! He even had famous South Korean director, Shin Sang-Ok, and his wife kidnapped in 1978 by the North Korean secret service. He then ordered the famous director from South Korea to make movies for him, providing him with all the money he needed to produce them. He directed more than 20 movies, many of them propaganda. The director was then jailed for having tried to escape. They couple finally managed to successfully flee in 1986. The following year, the Pyongyang Film Festival of Non-Aligned and Other Developing Countries began. -

North Korea Chemical Chronology

North Korea Chemical Chronology Last update: October 2012 This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation. 2012‐2009 6 January 2012 The Daily Yomiuri reports that diplomatic sources within the UN will soon launch an investigation of an attempted North Korean transfer of military‐use anti‐chemical weapons suits and chemical reagents to Syria that occurred in November 2009. In addition to the 14,000 suits already reported in 2011, The Yomiuri adds that a box of glass ampules carrying liquid or powdered reagents was also seized. The reagents can be used to detect airborne chemical agents in an offensive or defensive capacity during a chemical attack. Greek authorities intercepted the North Korean shipment from a Liberian‐flagged ship bound for Syria. — Michinobu Yanagisawa, N. Korea Tried to Ship WMD Reagent in '09 / U.N. to Launch Probe into Arms Violation,” The Daily Yomiuri, 6 January 2012, www.yomiuri.co.jp. -

KCNA FILE NO. 18 the Proposed Agreement, This KCNA Story Serves As a Reminder to Both North and South Koreans of the History Between Themselves and Japan

SINO-NK.COM KOREAN CENTRAL NEWS AGENCY FILE NO. 18 1 July 2012 –14 July 2012 Analysis: Of the 21 stories published about China by KCNA for this two- week period, 14 relating in a specific way the relationship between China and the DPRK. As with KCNA File No. 17, this latest batch of stories seems focused on ensuring both North Korean and foreign readers are reminded of the strength of the traditional alliance with China, the reliable safety net. In addition to the usual delegations, coverage was granted to Mt. Chilbo as a tourist destination for Chinese citizens, and stories about commemoration of DPRK leaders by Chinese citizens. Undoubtedly the important topic covered was the celebrations surrounding the 51st anniversary of the signing of the DPRK-China treaty. Four stories were published devoted solely to the coverage of this important event, which among other things detailed remarks by Liu Hongcai, the Chinese ambassador to North Korea, at a banquet. In remarks by Choe Chang Sik, the North Korean official stated that “It was the last instructions of General Secretary Kim Jong Il […] to boost the DPRK-China friendly and cooperative relations.” It seems that this anniversary could not have come at a better time for the DPRK as it continues to find itself in disputes where the presence of China as an ally has greatly been to North Korea’s benefit. Finally, a three stories were published about the rave reviews the DPRK’s opera “The Flower Girl” is receiving from theatregoers in China. This unusual amount of coverage for an ostensibly non-political story might have been utilized by KCNA and the DPRK leadership to demonstrate the increasing cultural exchange between the two allies. -

U.S. Bilateral Food Assistance to North Korea Had Mixed Results

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman and Ranking GAO Minority Member, Committee on International Relations, House of Representatives June 2000 FOREIGN ASSISTANCE U.S. Bilateral Food Assistance to North Korea Had Mixed Results GAO/NSIAD-00-175 Contents Letter 3 Appendixes Appendix I: Scope and Methodology 52 Appendix II: Accountability Related Problems Raised by International Agencies and Nongovernmental Organizations 55 Appendix III: Comments From the U.S. Agency for International Development 59 Appendix IV: GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 64 Table Table 1: Comparison of Scheduled and Actual Food Aid Deliveries for the Bilateral Assistance Project, May 1999 to November 1999 33 Figures Figure 1: Province and Counties Where the Chinese Seed Potatoes Were Planted 16 Figure 2: Type and Number of Food-for-Work Projects, Metric Tons of Food Distributed, and Beneficiaries by North Korean Administrative Districts 28 Figure 3: Percentage Distribution of the 100,000 Metric Tons of Food Aid by Administrative District, August 1999 to May 2000 29 Figure 4: Percentage Distribution of the 100,000 Metric Tons of Food Aid by Type of Food-for-Work Project, August 1999 to May 2000 30 Abbreviations USAID U.S. Agency for International Development USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture Page 1 GAO/NSIAD-00-175 Foreign Assistance Page 2 GAO/NSIAD-00-175 Foreign Assistance United States General Accounting Office National Security and Washington, D.C. 20548 International Affairs Division B-285415 Leter June 15, 2000 The Honorable Benjamin Gilman Chairman The Honorable Sam Gejdenson Ranking Minority Member Committee on International Relations House of Representatives Following North Korea’s agreement to provide the United States access to inspect a suspected underground nuclear facility at Kumchang-ni in March 1999, the administration announced it would take a modest step to facilitate an improvement in relations with North Korea in the form of the first U.S. -

Persecuting Faith: Documenting Religious Freedom Violations in North Korea

Persecuting Faith: Documenting religious freedom violations in North Korea Volume I Persecuting Faith: Documenting religious freedom violations in North Korea Volume I Korea Future Initiative October 2020 About Korea Future Initiative Korea Future Initiative is a non-profit charitable organisation whose mission is to equip governments and international organisations with authoritative human rights information that can support strategies to effect tangible and positive change in North Korea. www.koreafuture.org Recommended Citation Korea Future Initiative (2020). ‘Persecuting Faith: Documenting religious freedom violations in North Korea’. London: United Kingdom. Report Illustrations © 2020 Kim Haeun Copyright CC-BY-NC-ND This license requires that re-users give credit to the creator. It allows re-users to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format, for non-commercial purposes only. If others remix, adapt, or build upon the material, they may not distribute the modified material. Persecuting Faith: Documenting religious freedom violations in North Korea by Korea Future Initiative is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Acknowledgements Authors Hae Ju Kang Suyeon Yoo James Burt Korea Future Initiative benefitted from the support and expertise of diaspora organisations and exiled individuals throughout the process of investigating and documenting religious freedom violations. Specifically, our thanks are extended to Tongil Somang and to the interviewees who shared their experiences with investigators. In addition, we thank Jangdaehyun School. In planning investigations, undertaking analyses of the investigation findings, and drafting this report, Korea Future Initiative received significant support from Stephen Hathorn. -

Songbun North Korea’S Social Classification System

Marked for Life: Songbun North Korea’s Social Classification System A Robert Collins Marked for Life: SONGBUN, North Korea’s Social Classification System Marked for Life: Songbun North Korea’s Social Classification System Robert Collins The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 435, Washington, DC 20036 202-499-7973 www.hrnk.org Copyright © 2012 by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0985648007 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012939299 Marked for Life: SONGBUN, North Korea’s Social Classification System Robert Collins The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Ave. NW Suite 435 Washington DC 20036 (202) 499-7973 www.hrnk.org BOARD OF DIRECTORS, Jack David Committee for Human Rights in Senior Fellow and Trustee, Hudson Institute North Korea Paula Dobriansky Former Under Secretary of State for Democ- Roberta Cohen racy and Global Affairs Co-Chair, Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution Nicholas Eberstadt Resident Fellow, American Enterprise Institute Andrew Natsios Co-Chair, Carl Gershman Walsh School of Foreign Service Georgetown President, National Endowment for Democracy University, Former Administrator, USAID David L. Kim Gordon Flake The Asia Foundation Co-Vice-Chair, Executive Director, Maureen and Mike Mans- Steve Kahng field Foundation General Partner, 4C Ventures, Inc. Suzanne Scholte Katrina Lantos Swett Co-Vice-Chair, President, Lantos Foundation for Human Rights Chairman, North Korea Freedom Coalition and Justice John Despres Thai Lee Treasurer, President and CEO, SHI International Corp. Consultant, International Financial and Strate- Debra Liang-Fenton gic Affairs Former Executive Director, Committee for Hu- Helen-Louise Hunter man Rights in North Korea, Secretary, The U.S.