Winstanley-Chesters, BAKS Papers 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies

School of Oriental and African Studies University of London SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies No. 45 Producing Political Landscape on the Korean Peninsula: Divided Visions, United Vista Dr Robert Winstanley-Chesters & Ms Sherri L. Ter Molen May 2015 PRODUCING POLITICAL LANDSCAPE Producing Political Landscape on the Korean Peninsula: Divided Visions, United Vista Dr. Robert Winstanley-Chesters Beyond the Korean War Project (University of Cambridge) University of Leeds Ms. Sherri L. Ter Molen Wayne State University Author Note Dr. Robert Winstanley-Chesters is a Post-Doctoral Fellow of the Beyond the Korean War Project (University of Cambridge) and a Visiting Research Fellow at the School of Geography, University of Leeds. Sherri L. Ter Molen, A.B.D., is currently a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Communication, Wayne State University. The research for this article and project has received generous support from the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2010-DZZ-3104). Correspondence this article should be addressed to Dr. Robert Winstanley-Chesters at [email protected]. 1 PRODUCING POLITICAL LANDSCAPE Abstract Myths of national construction and accompanying visual representations are often deeply connected to political narrative. The Korean peninsula may be unlike other political space due to the ruptured relations and sovereignty on its territory since World War II: North and South Korea. Nevertheless, both nations construct inverse ideologies with the common tools of the pen and lens and both produce highly coded, -

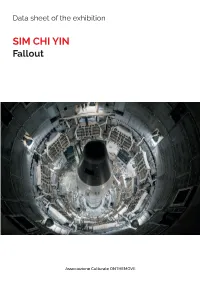

SIM CHI YIN Fallout

Data sheet of the exhibition SIM CHI YIN Fallout Associazione Culturale ONTHEMOVE DATA SHEET OF THE EXHIBITION | Fallout - Sim Chi Yin Fallout Sim Chi Yin Produced by Associazione culturale ONTHEMOVE in occasion of the Internation Photography Festival Cortona On The Move 2018 Curated by Arianna Rinaldo For information Antonio Carloni Director [email protected] +39 3286438076 Associazione culturale ONTHEMOVE | Località Vallone, 39/A/4 - Cortona, 52044 (AR) DATA SHEET OF THE EXHIBITION | Fallout - Sim Chi Yin Title Fallout Photographer Sim Chi Yin Curated by* Arianna Rinaldo Type of prints and mounting 17 color prints mounted on dilite Size of prints 11 prints 80 x 120 cm 5 prints 105 x 157 1 prints 105 x 144 cm Frames No frames. Prints are mounted on dilite (similar to dibond). Slider spacers in the back to be hung. Linear development 23 linear mt minimum (spaces not included) Video “Most people were silent”, 2017 Two-channel video installation with sound, 3:40 Set up annotations Text material must be printed at the expense of the hosting organization. We provide introduction text, biography and captions both in italian and english. *any changes to the selection or layout of the exhibition must be consulted with the curator Associazione culturale ONTHEMOVE | Località Vallone, 39/A/4 - Cortona, 52044 (AR) DATA SHEET OF THE EXHIBITION | Fallout - Sim Chi Yin FALLOUT In the pitch darkness, a single light reflected over the shallow waters of the Tumen river. All that was visible on the far shore was a pair of giant portraits: of North Korean founder Kim Il-sung and his son and successor Kim Jong-il. -

STATEMENT UPR Pre-Session 33 on the Democratic People's Republic

STATEMENT UPR Pre-Session 33 on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) Geneva, April 5, 2019 Delivered by: The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK) 1- Presentation of the Organization HRNK is the leading U.S.-based bipartisan, non-governmental organization (NGO) in the field of DPRK human rights research and advocacy. Our mission is to focus international attention on human rights abuses in the DPRK and advocate for an improvement in the lives of 25 million DPRK citizens. Since its establishment in 2001, HRNK has played an intellectual leadership role in DPRK human rights issues by publishing over thirty-five major reports. HRNK was granted UN consultative status on April 17, 2018 by the 54-member UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). On October 4, 2018, HRNK submitted our findings to the UPR of the DPRK. Based on our research, the following trends have defined the human rights situation in the DPRK over the past seven years: an intensive crackdown on attempted escape from the country leading to a higher number of prisoners in detention; a closure of prison camps near the border with China while camps inland were expanded; satellite imagery analysis revealing secure perimeters inside these detention facilities with watch towers seemingly located to provide overlapping fields of fire to prevent escapes; a disproportionate repression of women (800 out of 1000 women at Camp No. 12 were forcibly repatriated); and an aggressive purge of senior officials. 2- National consultation for the drafting of the national report Although HRNK would welcome consultation and in-country access to assess the human rights situation, the DPRK government displays a consistently antagonistic attitude towards our organization. -

North Korea Chemical Chronology

North Korea Chemical Chronology Last update: October 2012 This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation. 2012‐2009 6 January 2012 The Daily Yomiuri reports that diplomatic sources within the UN will soon launch an investigation of an attempted North Korean transfer of military‐use anti‐chemical weapons suits and chemical reagents to Syria that occurred in November 2009. In addition to the 14,000 suits already reported in 2011, The Yomiuri adds that a box of glass ampules carrying liquid or powdered reagents was also seized. The reagents can be used to detect airborne chemical agents in an offensive or defensive capacity during a chemical attack. Greek authorities intercepted the North Korean shipment from a Liberian‐flagged ship bound for Syria. — Michinobu Yanagisawa, N. Korea Tried to Ship WMD Reagent in '09 / U.N. to Launch Probe into Arms Violation,” The Daily Yomiuri, 6 January 2012, www.yomiuri.co.jp. -

U.S. Bilateral Food Assistance to North Korea Had Mixed Results

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman and Ranking GAO Minority Member, Committee on International Relations, House of Representatives June 2000 FOREIGN ASSISTANCE U.S. Bilateral Food Assistance to North Korea Had Mixed Results GAO/NSIAD-00-175 Contents Letter 3 Appendixes Appendix I: Scope and Methodology 52 Appendix II: Accountability Related Problems Raised by International Agencies and Nongovernmental Organizations 55 Appendix III: Comments From the U.S. Agency for International Development 59 Appendix IV: GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 64 Table Table 1: Comparison of Scheduled and Actual Food Aid Deliveries for the Bilateral Assistance Project, May 1999 to November 1999 33 Figures Figure 1: Province and Counties Where the Chinese Seed Potatoes Were Planted 16 Figure 2: Type and Number of Food-for-Work Projects, Metric Tons of Food Distributed, and Beneficiaries by North Korean Administrative Districts 28 Figure 3: Percentage Distribution of the 100,000 Metric Tons of Food Aid by Administrative District, August 1999 to May 2000 29 Figure 4: Percentage Distribution of the 100,000 Metric Tons of Food Aid by Type of Food-for-Work Project, August 1999 to May 2000 30 Abbreviations USAID U.S. Agency for International Development USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture Page 1 GAO/NSIAD-00-175 Foreign Assistance Page 2 GAO/NSIAD-00-175 Foreign Assistance United States General Accounting Office National Security and Washington, D.C. 20548 International Affairs Division B-285415 Leter June 15, 2000 The Honorable Benjamin Gilman Chairman The Honorable Sam Gejdenson Ranking Minority Member Committee on International Relations House of Representatives Following North Korea’s agreement to provide the United States access to inspect a suspected underground nuclear facility at Kumchang-ni in March 1999, the administration announced it would take a modest step to facilitate an improvement in relations with North Korea in the form of the first U.S. -

Persecuting Faith: Documenting Religious Freedom Violations in North Korea

Persecuting Faith: Documenting religious freedom violations in North Korea Volume I Persecuting Faith: Documenting religious freedom violations in North Korea Volume I Korea Future Initiative October 2020 About Korea Future Initiative Korea Future Initiative is a non-profit charitable organisation whose mission is to equip governments and international organisations with authoritative human rights information that can support strategies to effect tangible and positive change in North Korea. www.koreafuture.org Recommended Citation Korea Future Initiative (2020). ‘Persecuting Faith: Documenting religious freedom violations in North Korea’. London: United Kingdom. Report Illustrations © 2020 Kim Haeun Copyright CC-BY-NC-ND This license requires that re-users give credit to the creator. It allows re-users to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format, for non-commercial purposes only. If others remix, adapt, or build upon the material, they may not distribute the modified material. Persecuting Faith: Documenting religious freedom violations in North Korea by Korea Future Initiative is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Acknowledgements Authors Hae Ju Kang Suyeon Yoo James Burt Korea Future Initiative benefitted from the support and expertise of diaspora organisations and exiled individuals throughout the process of investigating and documenting religious freedom violations. Specifically, our thanks are extended to Tongil Somang and to the interviewees who shared their experiences with investigators. In addition, we thank Jangdaehyun School. In planning investigations, undertaking analyses of the investigation findings, and drafting this report, Korea Future Initiative received significant support from Stephen Hathorn. -

Songbun North Korea’S Social Classification System

Marked for Life: Songbun North Korea’s Social Classification System A Robert Collins Marked for Life: SONGBUN, North Korea’s Social Classification System Marked for Life: Songbun North Korea’s Social Classification System Robert Collins The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 435, Washington, DC 20036 202-499-7973 www.hrnk.org Copyright © 2012 by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0985648007 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012939299 Marked for Life: SONGBUN, North Korea’s Social Classification System Robert Collins The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Ave. NW Suite 435 Washington DC 20036 (202) 499-7973 www.hrnk.org BOARD OF DIRECTORS, Jack David Committee for Human Rights in Senior Fellow and Trustee, Hudson Institute North Korea Paula Dobriansky Former Under Secretary of State for Democ- Roberta Cohen racy and Global Affairs Co-Chair, Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution Nicholas Eberstadt Resident Fellow, American Enterprise Institute Andrew Natsios Co-Chair, Carl Gershman Walsh School of Foreign Service Georgetown President, National Endowment for Democracy University, Former Administrator, USAID David L. Kim Gordon Flake The Asia Foundation Co-Vice-Chair, Executive Director, Maureen and Mike Mans- Steve Kahng field Foundation General Partner, 4C Ventures, Inc. Suzanne Scholte Katrina Lantos Swett Co-Vice-Chair, President, Lantos Foundation for Human Rights Chairman, North Korea Freedom Coalition and Justice John Despres Thai Lee Treasurer, President and CEO, SHI International Corp. Consultant, International Financial and Strate- Debra Liang-Fenton gic Affairs Former Executive Director, Committee for Hu- Helen-Louise Hunter man Rights in North Korea, Secretary, The U.S. -

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-Making Under Kim Jong-Un a First Year Assessment

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-making under Kim Jong-un A First Year Assessment Ken E. Gause Cleared for public release COP-2013-U-005684-Final September 2013 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the glob- al community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “prob- lem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the follow- ing areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Appeal 28/97

DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF 23 October 1998 KOREA: HEALTH AND NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT appeal no. 28/97 situation report no. 06 period covered: 14 August - 14 October 1998 The joint International Federation/Red Cross Society of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea health and nutritional programme, begun in November 1997, is now approaching completion and planning for 1999 is underway. As winter approaches, the planned winterisation programme must be given priority to ensure the needs of vulnerable people living in remote, mountainous areas. The context Following major flood disasters in 1995 and 1996, the drought in 1997 and the decline in the economic situation in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, it became clear that urgent health requirements needed to be addressed at both the provincial/county levels and the ri-levels. The overall Red Cross programme in DPRK is made up of four distinct but closely interconnected components; health, food, disaster preparedness and winterisation. The programme continues to assist some 3.5 million beneficiaries in 25 counties in the Red Cross operational areas of Chagang Province and North Pyongan Province. The health project supplies essential drugs to 853 health institutions as well as training to some 12,000 medical personnel. Latest events The DPRK has so far largely escaped the widespread flooding that has affected parts of China and the Republic of Korea but has experienced severe localised flooding in the east and west of the country following torrential rain in late August. The Flood Disaster Rehabilitation Committee (FDRC) organised a three day assessment mission to the affected area for representatives from OCHA, WFP, UNDP, FAO, WHO, UNICEF and the International Federation. -

North Korea Designations; North Korea Administrative Update; Counter Terrorism Desig

North Korea Designations; North Korea Administrative Update; Counter Terrorism Desig... Page 1 of 32 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Resource Center North Korea Designations; North Korea Administrative Update; Counter Terrorism Designations 10/4/2018 OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL Specially Designated Nationals List Update The following individuals have been added to OFAC's SDN List: AL-AMIN, Muhammad 'Abdallah (a.k.a. AL AMEEN, Mohamed Abdullah; a.k.a. AL AMIN, Mohammad; a.k.a. AL AMIN, Muhammad Abdallah; a.k.a. AL AMIN, Muhammed; a.k.a. AL-AMIN, Mohamad; a.k.a. ALAMIN, Mohamed; a.k.a. AMINE, Mohamed Abdalla; a.k.a. EL AMINE, Muhammed), Yusif Mishkhas T: 3 Ibn Sina, Bayrut Marjayoun, Lebanon; Beirut, Lebanon; DOB 11 Jan 1975; POB El Mezraah, Beirut, Lebanon; nationality Lebanon; Additional Sanctions Information - Subject to Secondary Sanctions Pursuant to the Hizballah Financial Sanctions Regulations; Gender Male (individual) [SDGT] (Linked To: TABAJA, Adham Husayn). CULHA, Erhan; DOB 17 Oct 1954; POB Istanbul, Turkey; nationality Turkey; Gender Male; Secondary sanctions risk: North Korea Sanctions Regulations, sections 510.201 and 510.210; Passport U09787534 (Turkey) issued 12 Sep 2014 expires 12 Sep 2024; Personal ID Card 10589535602; General Manager (individual) [DPRK] (Linked To: SIA FALCON INTERNATIONAL GROUP). RI, Song Un, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia; DOB 16 Dec 1955; POB N. Hwanghae, North Korea; nationality Korea, North; Gender Male; Secondary sanctions risk: North Korea Sanctions Regulations, sections 510.201 and 510.210; Passport 836110063 (Korea, North) issued 04 Feb 2016 expires 04 Feb 2021; Economic and Commercial Counsellor at DPRK Embassy in Mongolia (individual) [DPRK2]. -

The North Korea Mega Tour

The North Korea Mega Tour TOUR September 3rd – 26th 2020 25 nights in North Korea + travel time OVERVIEW Koryo Tours' annual Mega Tour every September is the ultimate journey to North Korea, and our longest and most comprehensive tour to North Korea. We'll travel from Pyongyang, Panmunjom and the DMZ to stunning Mt Paektu, Mt Chilbo, and Mt Kumgang as well as the rarely-visited industrial cities of Chongjin, Hamhung, and Wonsan, plus much more. Updated for 2020 with new locations and activities, this is our longest tour to date. The trip covers thousands of kilometres from the capital Pyongyang to the country's far north, south, east, and west by bus and internal flights. On the way, we'll stop by all the must-see tourist attractions - from massive political structures and monuments to pristine mountains, forests, and beaches to the socialist industry and agriculture that are the backbone of the DPRK economy. We'll also be in Pyongyang for National Day, a major North Korean holiday, and see how North Koreans celebrate the 72nd anniversary of the foundation of the DPRK. Get to know one of the least-understood countries in the world and its people as it stands at a crossroads in its relations with its long-time adversaries: South Korea and the United States. The best way to get to know and understand North Korea is to spend time in the country and meet and interact with local North Koreans through activities, sports, games, and serendipitous encounters. A new addition to this tour is the possibility of extending your stay in the DPRK for two more nights to visit the Rason Special Economic Zone to see North Korea to its fullest like nobody before. -

Domestic Politics and Stakeholders in the North Korean Missile Development Program

Domestic Politics and Stakeholders in the North Korean Missile Development Program DANIEL A. PINKSTON Daniel A. Pinkston is a senior research associate and Korea specialist at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies in Monterey, California.1 he Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (here- earnings from exports. In the DPRK case, the missile after “the DPRK” or “North Korea”) and its mis- development program has tremendous distributional con- Tsile development program have generated inter- sequences for North Korean society, which includes a num- national concerns for several years. Most analysts agree ber of “stakeholders” with different preferences for the that the DPRK missile program is a threat to security and future of the missile program. stability in Northeast Asia and other regions, and North Given that Pyongyang’s policymakers must consider Korea’s missile exports are well documented. The Bush both international and domestic politics when deciding administration has accused Pyongyang of being “the missile development policy, predicting the future devel- world’s number one merchant for ballistic missiles—open opment path of the North Korean missile program is a for business with anyone, no matter how maligned the complex task. Most analysis tends to focus on the inter- buyer’s intentions.”2 national component of this problem, with little consider- Clearly North Korea’s missile program has had an ation for North Korean domestic politics and institutions. impact on international security; conversely, international Some analysts might argue that domestic politics is irrel- variables, or changes in the international strategic envi- evant because the North Korean leadership is completely ronment, influence the DPRK in determining the insulated from domestic pressures, or because all political program’s scope and future development.