The Population of North Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd in Political Economy & Government 1992–2017

Harvard Kennedy School Job Placement PHD IN POLITICAL ECONOMY & GOVERNMENT 1992–2017 Doctoral Programs Harvard Kennedy School 79 John F. Kennedy Street Littauer Building, Room 133 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 www.hks.harvard.edu/phd [email protected] 617-496-4485 Updated 10/17 2016–2017 Marek Hlavac Sara Lowes Economics Teacher, UWC Adriatic Assistant Professor, Bocconi University Danial Lashkari Assistant Professor, Boston College, Department of Economics 2015–2016 Guilherme Lichand Assistant Professor, University of Zurich, Department of Economics 2014–2015 Mauricio Fernandez Duque James Mahon Post-doctoral Research Fellow, Harvard University Manager, Deloitte Tax, Transfer Pricing Division Angela Fonseca Galvis Jesse Schreger Assistant Professor, Universidad Javeriana Assistant Professor, Harvard Business School Sabrina Howell (Post-doc at Princeton, Department of Economics) Assistant Professor, New York University Stern, Oren Ziv Department of Finance Assistant Professor, Michigan State University, Akos Lada Economics Department (Post-Doc at Dartmouth College) Economist, Facebook, Core Data Science Division 2013–2014 Jessica Blankshain Arash Nekoei Assistant Professor, United States Naval College Assistant Professor of Economics, Institute for Joana Naritomi Economic Studies Assistant Professor of Economics, London Hye Young You School of Economics Assistant Professor, Vanderbilt University, Department of Political Science 2012–2013 Paul Novosad Assistant Professor of Economics, Dartmouth College 2011–2012 Tim Ganser Supreet Kaur -

Ballast Water Risk Assessment Final Report

Ballast Water Risk Assessment Ballast Water Global Ballast Water Management Programme GLOBALLAST MONOGRAPH SERIES NO.12 Port of Dalian, People’s Republic of China Port of Dalian, People’s Ballast Water Risk Assessment Port of Dalian People’s Republic of China Final Report NOVEMBER 2003 Final Report Chris Clarke, Rob Hilliard, Liuy Yan, John Polglaze, Xu Xiaoman, GLOBALLAST MONOGRAPH SERIES Zhao Dianrong & Steve Raaymakers More Information? Programme Coordination Unit Global Ballast Water Management Programme International Maritime Organization 4 Albert Embankment London SE1 7SR United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7587 3247 or 3251 Fax: +44 (0)20 7587 3261 Web: http://globallast.imo.org NO.12 A cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility, United Nations Development Programme and International Maritime Organization. Cover designed by Daniel West & Associates, London. Tel (+44) 020 7928 5888 www.dwa.uk.com (+44) 020 7928 5888 www.dwa.uk.com & Associates, London. Tel Cover designed by Daniel West GloBallast Monograph Series No. 12 Ballast Water Risk Assessment Port of Dalian People’s Republic of China November 2003 Final Report Chris Clarke1, Rob Hilliard1, Liuy Yan3, John Polglaze1, Xu Xiaoman3, Zhao Dianrong2 & Steve Raaymakers4 1 URS Australia Pty Ltd, Perth, Western Australia 2 Liaoning Maritime Safety Administration, Dalian 3 China Maritime Safety Administration, Beijing 4 Programme Coordination Unit, GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme, International Maritime Organization ! International Maritime Organization ISSN 1680-3078 Published in April 2004 by the Programme Coordination Unit Global Ballast Water Management Programme International Maritime Organization 4 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7SR, UK Tel +44 (0)20 7587 3251 Fax +44 (0)20 7587 3261 Email [email protected] Web http://globallast.imo.org The correct citation of this report is: Clarke, C., Hilliard, R., Liuy, Y., Polglaze, J., Zhao, D., Xu, X. -

Pdf | 431.24 Kb

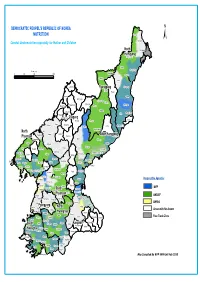

DEMOCRATIC PEOPEL'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA NUTRITION Onsong Kyongwon ± Combat Undernutrition especially for Mother and Children North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Musan Chongjin City Kilometers Taehongdan 050 100 200 Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Kanggye City Chagang Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Responsible Agencies Sunchon City Kowon Sukchon Sinyang Sudong WFP Pyongsong City South Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan UNICEF Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Kangso Sinpyong Popdong UNFPA PyongyangKangnam Thongchon Onchon Junghwa YonsanNorth Kosan Taean Sangwon Areas with No Access Nampo City Hwangju HwanghaeKoksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Free Trade Zone Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City Singye Changdo South Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Kangwon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Jaeryong HwanghaeSonghwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Kangryong Map Compiled By WFP VAM Unit Feb 2010. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Bay to Bay: China's Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US And

June 2021 Bay to Bay China’s Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US and San Francisco Bay Area Business Acknowledgments Contents This report was prepared by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute for the Hong Kong Trade Executive Summary ...................................................1 Development Council (HKTDC). Sean Randolph, Senior Director at the Institute, led the analysis with support from Overview ...................................................................5 Niels Erich, a consultant to the Institute who co-authored Historic Significance ................................................... 6 the paper. The Economic Institute is grateful for the valuable information and insights provided by a number Cooperative Goals ..................................................... 7 of subject matter experts who shared their views: Louis CHAPTER 1 Chan (Assistant Principal Economist, Global Research, China’s Trade Portal and Laboratory for Innovation ...9 Hong Kong Trade Development Council); Gary Reischel GBA Core Cities ....................................................... 10 (Founding Managing Partner, Qiming Venture Partners); Peter Fuhrman (CEO, China First Capital); Robbie Tian GBA Key Node Cities............................................... 12 (Director, International Cooperation Group, Shanghai Regional Development Strategy .............................. 13 Institute of Science and Technology Policy); Peijun Duan (Visiting Scholar, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies Connecting the Dots .............................................. -

China Russia

1 1 1 1 Acheng 3 Lesozavodsk 3 4 4 0 Didao Jixi 5 0 5 Shuangcheng Shangzhi Link? ou ? ? ? ? Hengshan ? 5 SEA OF 5 4 4 Yushu Wuchang OKHOTSK Dehui Mudanjiang Shulan Dalnegorsk Nongan Hailin Jiutai Jishu CHINA Kavalerovo Jilin Jiaohe Changchun RUSSIA Dunhua Uglekamensk HOKKAIDOO Panshi Huadian Tumen Partizansk Sapporo Hunchun Vladivostok Liaoyuan Chaoyang Longjing Yanji Nahodka Meihekou Helong Hunjiang Najin Badaojiang Tong Hua Hyesan Kanggye Aomori Kimchaek AOMORI ? ? 0 AKITA 0 4 DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S 4 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Akita Morioka IWATE SEA O F Pyongyang GULF OF KOREA JAPAN Nampo YAMAJGATAA PAN Yamagata MIYAGI Sendai Haeju Niigata Euijeongbu Chuncheon Bucheon Seoul NIIGATA Weonju Incheon Anyang ISIKAWA ChechonREPUBLIC OF HUKUSIMA Suweon KOREA TOTIGI Cheonan Chungju Toyama Cheongju Kanazawa GUNMA IBARAKI TOYAMA PACIFIC OCEAN Nagano Mito Andong Maebashi Daejeon Fukui NAGANO Kunsan Daegu Pohang HUKUI SAITAMA Taegu YAMANASI TOOKYOO YELLOW Ulsan Tottori GIFU Tokyo Matsue Gifu Kofu Chiba SEA TOTTORI Kawasaki KANAGAWA Kwangju Masan KYOOTO Yokohama Pusan SIMANE Nagoya KANAGAWA TIBA ? HYOOGO Kyoto SIGA SIZUOKA ? 5 Suncheon Chinhae 5 3 Otsu AITI 3 OKAYAMA Kobe Nara Shizuoka Yeosu HIROSIMA Okayama Tsu KAGAWA HYOOGO Hiroshima OOSAKA Osaka MIE YAMAGUTI OOSAKA Yamaguchi Takamatsu WAKAYAMA NARA JAPAN Tokushima Wakayama TOKUSIMA Matsuyama National Capital Fukuoka HUKUOKA WAKAYAMA Jeju EHIME Provincial Capital Cheju Oita Kochi SAGA KOOTI City, town EAST CHINA Saga OOITA Major Airport SEA NAGASAKI Kumamoto Roads Nagasaki KUMAMOTO Railroad Lake MIYAZAKI River, lake JAPAN KAGOSIMA Miyazaki International Boundary Provincial Boundary Kagoshima 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 Kilometers Miles 0 10 20 40 60 80 ? ? ? ? 0 5 0 5 3 3 4 4 1 1 1 1 The boundaries and names show n and t he designations us ed on this map do not imply of ficial endors ement or acceptance by the United N at ions. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

25 Interagency Map Pmedequipment.Mxd

Onsong Kyongwon North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Provision of Medical Equipment Musan Chongjin City Taehongdan Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Chagang Kanggye City Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Responsible Agency Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon WHO Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City UNFPA Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon UNICEF Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon IFRC Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan EUPS 1 Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Sunchon City Kowon EUPS 3 Sukchon SouthSinyang Sudong Pyongsong City Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon EUPS 7 PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Free Trade Zone Kangso Sinpyong Popdong PyongyangKangnam North Thongchon Onchon Junghwa Yonsan Kosan Taean Sangwon No Access Allowed Nampo City Hwanghae Hwangju Koksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City South Singye Kangwon Changdo Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Hwanghae Jaeryong Songhwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Map compliled by VAM Unit Kangryong WFP DPRK Feb 2010. -

The Situation Further to Determine If External Assistance Is Needed

Information bulletin Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Floods Information Bulletin n° 1 GLIDE n° FL-2013-000081-PRK 26 July 2013 Text box for brief photo caption. Example: In February 2007, the This bulletin is being issued for information Colombian Red Cross Society distributed urgently needed only, and reflects the current situation and materials after the floods and slides in Cochabamba. IFRC (Arial details available at this time. The 8/black colour) Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS), with the support of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is assessing the situation further to determine if external assistance is needed. Since 12-22 July 2013, most parts of DPRK were hit by consecutive floods and landslides caused by torrential rains. As of 23 July, DPRK government data reports 28 persons dead, 2 injured and 18 missing. A total of 3,742 families have lost their houses due to total and partial destruction and 49,052 people have been displaced. Red Cross volunteers were mobilized for early Red Cross volunteers are distributing the relief items to flood affected people in Anju City, South Pyongan province. Photo: DPRK RCS. warning and evacuation, search and rescue, first aid service, damage and need assessment, and distribution of relief items. The DPRK RCS with the support of IFRC has released 2,690 emergency relief kits, including quilts, cooking sets, tarpaulins, jerry cans, hygiene kits and water purification tablets which were distributed to 10,895 beneficiaries in Tosan County, North Hwanghae province and Anju City, South Pyongan province. -

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres, -

SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies

School of Oriental and African Studies University of London SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies No. 45 Producing Political Landscape on the Korean Peninsula: Divided Visions, United Vista Dr Robert Winstanley-Chesters & Ms Sherri L. Ter Molen May 2015 PRODUCING POLITICAL LANDSCAPE Producing Political Landscape on the Korean Peninsula: Divided Visions, United Vista Dr. Robert Winstanley-Chesters Beyond the Korean War Project (University of Cambridge) University of Leeds Ms. Sherri L. Ter Molen Wayne State University Author Note Dr. Robert Winstanley-Chesters is a Post-Doctoral Fellow of the Beyond the Korean War Project (University of Cambridge) and a Visiting Research Fellow at the School of Geography, University of Leeds. Sherri L. Ter Molen, A.B.D., is currently a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Communication, Wayne State University. The research for this article and project has received generous support from the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2010-DZZ-3104). Correspondence this article should be addressed to Dr. Robert Winstanley-Chesters at [email protected]. 1 PRODUCING POLITICAL LANDSCAPE Abstract Myths of national construction and accompanying visual representations are often deeply connected to political narrative. The Korean peninsula may be unlike other political space due to the ruptured relations and sovereignty on its territory since World War II: North and South Korea. Nevertheless, both nations construct inverse ideologies with the common tools of the pen and lens and both produce highly coded, -

Seismic Waves That Spread Through the Earth's Deep Interior

Seismic waves that spread through the Earth’s deep interior: BANG! or QUAKE! three stations at different distances from the sourc nces e ista 90º t d en er iff 60º d at s n o ti ta s e e r 30º h T CRUST (very thin) Seismic source CORE MANTLE 90º 60º 30º 90º 60º 30º 90º 60º 30º The wavefront position is shown after it has been traveling for several minutes. It continues to travel throughout the Earth's interior, bouncing off the core, and bouncing off the Earth's surface. 1.5 million seismic events since 1960, located by the International Seismological Centre on the basis of data from about 17,000 stations (up to ~ 6000 in any one year) 6L[GLIIHUHQWVWHSVLQQXFOHDUH[SORVLRQPRQLWRULQJ 'HWHFWLRQ GLGDSDUWLFXODUVWDWLRQGHWHFWDXVHIXOVLJQDO" $VVRFLDWLRQ FDQZHJDWKHUDOOWKHGLIIHUHQWVLJQDOVIURPWKHVDPH³HYHQW´" /RFDWLRQ ZKHUHZDVLW" ,GHQWLILFDWLRQ ZDVLWDQHDUWKTXDNHDPLQLQJEODVWDQXFOHDUZHDSRQWHVW" $WWULEXWLRQ LILWZDVDQXFOHDUWHVWZKDWFRXQWU\FDUULHGLWRXW" <LHOGHVWLPDWLRQ KRZELJZDVLW" MDJ 200 km HIA Russia 50°N 44°N HIA MDJ China USK BJT Chongjin 42° Japan 40° INCN KSRS MAJO 2006Oct09 MJAR Kimchaek SSE 30° 40° 120° 130° 140°E 126° 128° 130°E NIED seismic stations Hi-net 750 KiK-net 700 K-NET 1000 F-net 70 MDJ 200 km HIA Russia 50°N 44°N HIA MDJ China USK BJT Chongjin 42° Japan 40° INCN KSRS MAJO 2006Oct09 MJAR Kimchaek SSE 30° 40° 120° 130° 140°E 126° 128° 130°E Station Source crust mantle Pn - wave path (travels mostly in the mantle) Station Source crust mantle Pg - paths, in the crust, all with similar travel times Vertical Records at MDJ (Mudanjiang,