Historical Relations Between Poland and North Korea from 1948 to 1980*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 431.24 Kb

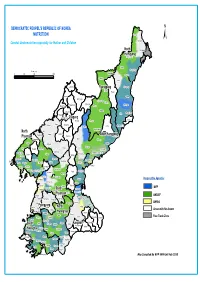

DEMOCRATIC PEOPEL'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA NUTRITION Onsong Kyongwon ± Combat Undernutrition especially for Mother and Children North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Musan Chongjin City Kilometers Taehongdan 050 100 200 Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Kanggye City Chagang Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Responsible Agencies Sunchon City Kowon Sukchon Sinyang Sudong WFP Pyongsong City South Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan UNICEF Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Kangso Sinpyong Popdong UNFPA PyongyangKangnam Thongchon Onchon Junghwa YonsanNorth Kosan Taean Sangwon Areas with No Access Nampo City Hwangju HwanghaeKoksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Free Trade Zone Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City Singye Changdo South Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Kangwon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Jaeryong HwanghaeSonghwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Kangryong Map Compiled By WFP VAM Unit Feb 2010. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

25 Interagency Map Pmedequipment.Mxd

Onsong Kyongwon North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Provision of Medical Equipment Musan Chongjin City Taehongdan Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Chagang Kanggye City Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Responsible Agency Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon WHO Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City UNFPA Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon UNICEF Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon IFRC Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan EUPS 1 Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Sunchon City Kowon EUPS 3 Sukchon SouthSinyang Sudong Pyongsong City Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon EUPS 7 PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Free Trade Zone Kangso Sinpyong Popdong PyongyangKangnam North Thongchon Onchon Junghwa Yonsan Kosan Taean Sangwon No Access Allowed Nampo City Hwanghae Hwangju Koksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City South Singye Kangwon Changdo Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Hwanghae Jaeryong Songhwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Map compliled by VAM Unit Kangryong WFP DPRK Feb 2010. -

Korea's Speciality Kaesong Koryo Insam

CONTENTS Δ Kim Jong Un Inspects Several Sectors ··································1 Δ Paduk with Time-honoured History ····································26 Δ Mt. Osong Tells ········································································4 Δ Performance Makes Popular Hit ········································28 Δ Jonsan Revolutionary Battle Site ·······································6 Δ Korea’s Speciality Δ Kimjongilia Exhibition held in China ···································8 Kaesong Koryo Insam ··················································30 Δ Pioneers on Sepho Tableland ·········································· 10 Δ National Day of Persons with Disabilities Marked ············32 Δ Various LED Lights Are Produced ·····································14 Δ Honey Bee “Doctor” in Hwangju ·········································34 Δ Renovated Sports Village on Chongchun Street ················16 Δ Koguryo Tomb with Murals Unearthed ···························35 Δ Koryo Ceramics Earn High Praise ···········································19 Δ Historical Relic Δ Village Appeared with the Construction Kwangbop Temple ·························································36 of Ryongnim Dam ······························································20 Δ Anti-“Government” Feelings Surge ·········································38 Δ Key to Victory ····································································22 Δ News Roundup ···································································40 Δ Young Scientist -

DPRK) So Far This Year

DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S 16 April 2004 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Appeal No. 01.68/2004 Appeal Target: CHF 14, 278, 310 Programme Update No. 01 Period covered: January – March 2004 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilising the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organisation and its millions of volunteers are active in over 180 countries. For more information: www.ifrc.org In Brief Appeal coverage: 36.3 %; See attached Contributions List for details. Outstanding needs: CHF 9,089,504 Related Emergency or Annual Appeals: 01.67/2003 Programme Summary: No major natural disasters have affected the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea (DPRK) so far this year. Food security is a major concern, especially in areas remote from the capital. The Red Cross Society of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK RC) has been granted permission from the government to expand the Federation supported health and care programme to another province, increasing the number of potential beneficiaries covered by the essential medicines programme to 8.8 million from July 2004. Due to delayed funding, the first quarter of 2004 has been used to finalise most of the programme activities from the 2003 appeal. Bilateral support from the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands and the Norwegian Red Cross Societies is supplementing Federation support. Partner national societies renewed their commitment to continue supporting DPRK RC. DPRK RC is regarded as an important organisation in DPRK by the government, donor country embassies, UN agencies and NGOs. Operational developments Harvests last year in DPRK were above average, however, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) state that, despite the good harvests, the situation remains “especially precarious” for young children, pregnant and nursing women and many elderly people. -

Korea's Economy

2016 Overview and Macroeconomic Issues Lessons from the Economic Development Experience of South Korea Danny Leipziger The Role of Aid in Korea's Development Lee Kye Woo Future Prospects for the Korean Economy Jung Kyu-Chul Building a Creative Economy The Creative Economy of the Park Geun-hye Administration Cha Doo-won The Real Korean Innovation Challenge: Services and Small Businesses ECONOMY VOLUME 31 KOREA’S Robert D. Atkinson Spurring the Development of Venture Capital in Korea Randall Jones Economic Relations with Europe KOREA’S ECONOMY Korea’s Economic Relations with the EU and the Korea-EU FTA a publication of the Korea Economic Institute of America Kang Yoo-duk VOLUME 31 and the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy 130 Years between Korea and Italy: Evaluation and Prospect Oh Tae Hyun 2014: 130 Years of Diplomatic Relations between Korea and Italy Angelo Gioe 130th Anniversary of Korea’s Economic Relations with Russia Jeong Yeo-cheon North Korea The Costs of Korean Unification: Realistic Lessons from the German Case Rudiger Frank President Park Geun-hye’s Unification Vision and Policy Jo Dongho Korea Economic Institute of America Korea Korea Economic Institute of America 1800 K Street, NW Suite 1010 Washington, DC 20006 CONTENTS KEI Board of Directors ................................................................................................................................ iv KEI Advisory Council .................................................................................................................................. -

April Birthday 7-Night Tour Itinerary for KITC

April Birthday 7-night Tour 7-night Tour: Fri, April 12 – Sat, April 20 DAY AM PM HOTEL Sat 13 • Dinner at Yanggakdo Hotel and regrouping Yanggakdo Hotel, Apr • Optional screening of Comrade Kim Goes Pyongyang Flying at the Pyongyang International Cinema Hall (Introduction by Nick Bonner) Sun 14th • Kumsusan Palace of the Sun • Chilgol Revolutionary Site Yanggakdo Hotel, April • Tram ride • Foreign Languages Bookshop Pyongyang • Kwangbok Department Store • Kim Il Sung Square • Mt. Ryonggak picnic and hike • Juche Tower • Golden Lane Bowling Alley • Dinner at the Pizza Restaurant (pax pays on spot) • Evening walk on Future Scientists Street Mon 15th • Mansudae Fountain Park • Party Foundation Monument Yanggakdo Hotel, April • Mansudae Grand Monument • Kimilsungia and Kimjongilia Flower Exhibition Pyongyang • Mangyongdae Native House • Mass Dance • Pyongyang Metro (6 stops) • Mansugyo Beer Bar • Arch of Triumph • Taedonggang River cruise • Moranbong Park with picnic lunch Tue 16th • Jonsung Revolutionary Site • Drive to Myohyangsan Huichon Hotel, April • Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum and • Pohyon Buddhist Temple Huichon county USS Peublo • Manpok Valley hike • Lunch at Okryugwan Wed 17th • International Friendship Exhibition • Drive to Pyongsong Ryonggang Hot April • Drive to Anju • Konji-Ri Revolutionary Site Spa Hotel, Nampo • Paeksang Pavilion and Anju City Walls • Kim Jong Suk Middle School • Drive to Nampo • Tae’an Glass Factory • Nampo Square Thu 18th • West Sea Barrage • Migok Cooperative Farm Misnok Hotel, April • Mt. Kuwol • Sariwon Folk Village and City View Kaesong • Woljong Temple • Drive to Kaesong • Janam Hill Fri 19th • Walk in Kaesong Old City • Concrete Wall and view of the DMZ Potonggang Hotel, April • Panmunjom/DMZ • Drive back to Pyongyang via Three Charters Pyongyang • Kaesong Koryo Museum and stamp shop Monument • Lunch with dog meat soup option • Grand People’s Study House • Kaeson Youth Funfair • Farewell dinner at Potonggang BBQ Sat 20th Flight departs at 08:30 n/a n/a April Train leaves at 10:25 . -

Academic Paper Series

Korea Economic Institute of America ACADEMIC PAPER SERIES NOVEMBER 30, 2017 Soap Operas and Socialism: Dissecting Kim Jong-un’s Evolving Policy Priorities through TV Dramas in North Korea By Jean Lee Abstract Introduction Romance, humor, tension — everyone loves a good sitcom, even Much has been written about North Korea’s film industry, the North Koreans. But in North Korea, TV dramas are more than beloved pet project of the late leader Kim Jong-il, who went mere entertainment. They play a crucial political role by serving to extreme lengths — including kidnapping his favorite South as a key messenger of party and government policy. They aim to Korean movie director and actress in 19781 — and lavishing shape social and cultural mores in North Korean society. And in millions on films in order to bring his cinematic fantasies to life.2 the Kim Jong-un era, they act as an advertisement for the “good However, since Kim Jong-il’s death in December 2011, this once- life” promised to the political elite. Through TV dramas, the North mighty arm of North Korea’s propaganda arts appears to have Korean people learn what the regime says constitutes being a languished under the rule of his millennial son Kim Jong-un. In good citizen in Kim Jong-un’s North Korea today: showing loyalty 2011, the last year of Kim Jong-il’s life, state-run film studios to the party, using science and technology to advance national released 10 feature films.3 In contrast, only one film was released interests, thinking creatively in problem-solving, and facing the in 2013 as Kim Jong-un’s new propaganda imperatives began nation’s continued economic hardships with a positive attitude. -

Koryo North Korea Budget Tour Autumn

Koryo North Korea Budget Tour Autumn TOUR November 16th – 20th 2021 4 nights in North Korea + Beijing-Pyongyang travel time OVERVIEW Budget North Korea tours are basic introductory tours for the frugal traveller in search of adventure. This no-frills alternative to our more advanced tours offers a great way to see a tightly edited package of the country’s most interesting sights, including a city tour of Pyongyang and a visit to the DMZ, where North and South Korea continue their decades-old face-off. You’ll also spend a night in the beautiful Mt Myohyang area, where we will visit the famous International Friendship Exhibition in the mountains and hike the Manpok Valley area through the autumn leaves. Our Koryo Budget North Korea Tours may be short, but they are action-packed and will only leave you wanting more! November too cold? We have a range of other budget tours throughout the year! THIS DOCUMENT CANNOT BE TAKEN INTO KOREA The Experts in Travel to Rather Unusual Destinations. [email protected] | +86 10 6416 7544 | www.koryotours.com 27 Bei Sanlitun Nan, Chaoyang District, 100027, Beijing, China DAILY ITINERARY NOVEMBER 15 – MONDAY *Pre-Tour Briefing | We require all travellers to attend a pre-tour briefing that covers regulations, etiquette, safety, and practicalities for travel in North Korea. The briefing lasts approximately one hour followed by a question and answer session. Please be punctual for the briefing. You can come early, meet your fellow travellers, pay any outstanding tour fees and browse our collection of Korean art. A proper briefing is an essential part of travel to North Korea. -

S P E C I a L R E P O

S P E C I A L R E P O R T FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION TO THE DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA 28 November 2013 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS, ROME WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME, ROME This report has been prepared by Kisan Gunjal and Swithun Goodbody (FAO) and Siemon Hollema, Katrien Ghoos, Samir Wanmali, Krishna Krishnamurthy and Emily Turano (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP Secretariats with information from official and other sources. The authors wish to acknowledge valuable contributions from Belay Gaga and Bui Bong (FAO) and Anna- Leena Rasanen, Xuerong Liu, Dawa Gyetse and Jennifer Rosenzweig (WFP). Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Liliana Balbi Kenro Oshidari Senior Economist, GIEWS, FAO Regional Director, WFP Fax: 0039-06-5705-4495 Fax: 0066-26554413 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web (www.fao.org ) at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Special Alerts/Reports can also be received automatically by E-mail as soon as they are published, by subscribing to the GIEWS/Alerts report ListServ. To do so, please send an E-mail to the FAO-Mail- Server at the following address: [email protected] , leaving the subject blank, with the following message: subscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L To be deleted from the list, send the message: unsubscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L Please note that it is now possible to subscribe to regional lists to only receive Special Reports/Alerts by region: Africa, Asia, Europe or Latin America (GIEWSAlertsAfrica-L, GIEWSAlertsAsia-L, GIEWSAlertsEurope-L and GIEWSAlertsLA-L). -

Songbun North Korea’S Social Classification System

Marked for Life: Songbun North Korea’s Social Classification System A Robert Collins Marked for Life: SONGBUN, North Korea’s Social Classification System Marked for Life: Songbun North Korea’s Social Classification System Robert Collins The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 435, Washington, DC 20036 202-499-7973 www.hrnk.org Copyright © 2012 by the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0985648007 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012939299 Marked for Life: SONGBUN, North Korea’s Social Classification System Robert Collins The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Ave. NW Suite 435 Washington DC 20036 (202) 499-7973 www.hrnk.org BOARD OF DIRECTORS, Jack David Committee for Human Rights in Senior Fellow and Trustee, Hudson Institute North Korea Paula Dobriansky Former Under Secretary of State for Democ- Roberta Cohen racy and Global Affairs Co-Chair, Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution Nicholas Eberstadt Resident Fellow, American Enterprise Institute Andrew Natsios Co-Chair, Carl Gershman Walsh School of Foreign Service Georgetown President, National Endowment for Democracy University, Former Administrator, USAID David L. Kim Gordon Flake The Asia Foundation Co-Vice-Chair, Executive Director, Maureen and Mike Mans- Steve Kahng field Foundation General Partner, 4C Ventures, Inc. Suzanne Scholte Katrina Lantos Swett Co-Vice-Chair, President, Lantos Foundation for Human Rights Chairman, North Korea Freedom Coalition and Justice John Despres Thai Lee Treasurer, President and CEO, SHI International Corp. Consultant, International Financial and Strate- Debra Liang-Fenton gic Affairs Former Executive Director, Committee for Hu- Helen-Louise Hunter man Rights in North Korea, Secretary, The U.S. -

Culturegramstm World Edition 2019 Japan

CultureGramsTM World Edition 2019 Japan until the late 19th century, however, feudal lords (or shoguns) BACKGROUND held political control. Japan adopted a policy of strict isolation and remained closed to nearly all foreign trade until Land and Climate 1853, when Matthew Perry of the U.S. Navy sailed into the Japan is slightly larger than Germany, or just smaller than the harbor of Edo (now Tokyo) to demand a treaty. The shoguns U.S. state of Montana. It consists of four main islands: lost power in the 1860s, and the emperor again took control. Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku. These are Hirohito ruled as emperor from 1926 to 1989. His reign surrounded by more than four thousand smaller islands. was called Shōwa, which means “enlightened peace,” and the Japan's terrain is largely mountainous, and most large cities deceased Hirohito is now properly referred to as Shōwa. He are positioned along the coasts. The country's wildlife is was succeeded by his eldest son, Akihito, in 1989. Akihito's diverse and includes animals such as bears, foxes, snow reign was called Heisei, meaning “achievement of universal monkeys, rabbits, deer, and red-crowned cranes. peace.” In 2019, due to the state of his health, Akihito stepped The nation has a few active and many dormant volcanoes. down as emperor, passing the throne to his eldest son, Mount Fuji, located west of Tokyo, on Honshu Island, is Naruhito, in Japan's first abdication since 1817. Japan's Japan's highest point, with an elevation of 12,388 feet (3,776 government chose Reiwa, meaning “beautiful harmony,” as meters).