Academic Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 431.24 Kb

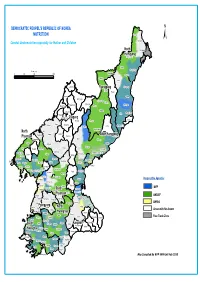

DEMOCRATIC PEOPEL'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA NUTRITION Onsong Kyongwon ± Combat Undernutrition especially for Mother and Children North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Musan Chongjin City Kilometers Taehongdan 050 100 200 Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Kanggye City Chagang Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Responsible Agencies Sunchon City Kowon Sukchon Sinyang Sudong WFP Pyongsong City South Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan UNICEF Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Kangso Sinpyong Popdong UNFPA PyongyangKangnam Thongchon Onchon Junghwa YonsanNorth Kosan Taean Sangwon Areas with No Access Nampo City Hwangju HwanghaeKoksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Free Trade Zone Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City Singye Changdo South Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Kangwon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Jaeryong HwanghaeSonghwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Kangryong Map Compiled By WFP VAM Unit Feb 2010. -

Exhibition Inscriptions

Photographs Prison/Concentration Camps Foreigners are closely followed at all times and are prohibited from leaving their hotels North Korea currently operates sixteen confirmed concentrations camps where up to at night. Photographs are only allowed in a small number of state-approved locations and 200,000 men, women and children are incarcerated. Some are the size of cities and mortality under no circumstances may they be taken of military personnel. In order to document real rates are high since prisoners are forced to perform dangerous slave work and are regularly life in North Korea, Daoust made use of a hidden shutter-release cable to take photographs tortured. Note: Many of those imprisoned are not guilty of any real crime: one man was sent secretly in the non-approved locations. to prison for ten years for absent-mindedly using a newspaper printed with a photograph of Kim Jong-Il to mop up a spilled drink. Pleasure Brigade Bicycles The Kippumjo or Gippeumjo (translated variously as Pleasure Squad, Pleasure Brigade or The late Kim Jong Il reportedly felt that the sight of a woman on a bike was potentially Joy Division) is an alleged collection of groups of approximately 2,000 women and girls dam-aging to public morality. It was the last straw when, in the mid nineties, the daughter of that is maintained by the head of state of North Korea for the purpose of providing pleasure, a top general was killed on a bike. From this point forward, the law has periodically banned mostly of a sexual nature, and entertainment for high-ranking Workers’ Party of Korea women from riding bicycles and they are generally restricted from holding driving licenses. -

A PARTNER for CHANGE the Asia Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 a PARTNER Characterizing 60 Years of Continuous Operations of Any Organization Is an Ambitious Task

SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION IN KOREA SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION A PARTNER FOR CHANGE A PARTNER The AsiA Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 A PARTNER Characterizing 60 years of continuous operations of any organization is an ambitious task. Attempting to do so in a nation that has witnessed fundamental and dynamic change is even more challenging. The Asia Foundation is unique among FOR foreign private organizations in Korea in that it has maintained a presence here for more than 60 years, and, throughout, has responded to the tumultuous and vibrant times by adapting to Korea’s own transformation. The achievement of this balance, CHANGE adapting to changing needs and assisting in the preservation of Korean identity while simultaneously responding to regional and global trends, has made The Asia Foundation’s work in SIX DECADES of Korea singular. The AsiA Foundation David Steinberg, Korea Representative 1963-68, 1994-98 in Korea www.asiafoundation.org 서적-표지.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:42 서적152X225-2.indd 4 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 A PARTNER FOR CHANGE Six Decades of The Asia Foundation in Korea 1954–2017 Written by Cho Tong-jae Park Tae-jin Edward Reed Edited by Meredith Sumpter John Rieger © 2017 by The Asia Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission by The Asia Foundation. 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

25 Interagency Map Pmedequipment.Mxd

Onsong Kyongwon North Kyonghung Hamgyong Hoiryong City Provision of Medical Equipment Musan Chongjin City Taehongdan Puryong Samjiyon Yonsa Junggang Ryanggang Kyongsong Pochon Paekam Jasong Orang Kimhyongjik Hyesan City Unhung Hwaphyong Kimjongsuk Myonggan Manpo City Samsu Kapsan Janggang Kilju Myongchon Sijung Chagang Kanggye City Rangrim Pungso Hwadae Chosan Wiwon Songgang Pujon Hochon Kimchaek City Kimhyonggwon North Usi Responsible Agency Kopung Jonchon South Hamgyong Phyongan Pyokdong Ryongrim Tanchon City Changsong Jangjin Toksong Sakju Songwon Riwon WHO Sinhung Uiju Tongsin Taegwan Tongchang Pukchong Huichon City Sinuiju City Hongwon Sinpho City UNFPA Chonma Unsan Yonggwang Phihyon Taehung Ryongchon Hyangsan Kusong City Hamhung City Sindo Nyongwon UNICEF Yomju Tongrim Thaechon Kujang Hamju Sonchon Rakwon Cholsan Nyongbyon IFRC Pakchon Tokchon City Kwaksan Jongju City Unjon Jongphyong Kaechon City Yodok Maengsan EUPS 1 Anju City Pukchang Mundok Kumya Sunchon City Kowon EUPS 3 Sukchon SouthSinyang Sudong Pyongsong City Chonnae Pyongwon Songchon EUPS 7 PhyonganYangdok Munchon City Jungsan Wonsan City Taedong Pyongyang City Kangdong Hoichang Anbyon Free Trade Zone Kangso Sinpyong Popdong PyongyangKangnam North Thongchon Onchon Junghwa Yonsan Kosan Taean Sangwon No Access Allowed Nampo City Hwanghae Hwangju Koksan Hoiyang Suan Pangyo Sepho Unchon Yontan Kumgang Kosong Unryul Sariwon City South Singye Kangwon Changdo Anak Pongsan Sohung Ichon Phyonggang Kwail Kimhwa Hwanghae Jaeryong Songhwa Samchon Unpha Phyongsan Sinchon Cholwon Jangyon Rinsan Tosan Ryongyon Sinwon Kumchon Taetan Pongchon Pyoksong Jangphung Haeju City Kaesong City Chongdan Ongjin Paechon Yonan Kaepung Map compliled by VAM Unit Kangryong WFP DPRK Feb 2010. -

Christmas in North Korea

Christmas in North Korea Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi With contributions from Talha Jilani Asad Alamgir Guven Uzun Suleman Khan Christmas in North Korea By Adnan I. Qureshi This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Adnan I. Qureshi All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5054-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5054-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contributors .............................................................................................. x Preface ...................................................................................................... xi 1. The Journey to North Korea ............................................................... 1 1.1. Introduction to the Korean Peninsula 1.2. Tour to North Korea 1.3. Introduction to The Pyongyang Times 1.4. Arrival at Pyongyang International Airport 2. Brief History ........................................................................................ 32 2.1. The ‘Three Kingdom’ and ‘Later Three Kingdom’ periods 2.2. Goryeo kingdom 2.3. Joseon kingdom 2.4. Japanese occupation 2.5. Complete Japanese control 2.6. Post-Japanese occupation 2.7. The Korean War 3. Contemporary North Korea .............................................................. 58 3.1. The first communist dynasty and its challenges 3.2. The changing face of the communist economic structure 3.3. Nuclear power 3.4. Rocket technology 3.5. Life amidst sanctions 3.6. Mineral resources 3.7. Mutual defense treaties 3.8. Governmental structure of North Korea 3.9. -

The Juche Tower in Pyongyang. Photo by Uwe Brodrecht, Used Under CC BY-SA 2.0 COMMENTARY: “WE MUST BE READY for REVENGE”: the REAL VALUE of CHILDHOOD in NORTH KOREA

The Juche Tower in Pyongyang. Photo by Uwe Brodrecht, used under CC BY-SA 2.0 COMMENTARY: “WE MUST BE READY FOR REVENGE”: THE REAL VALUE OF CHILDHOOD IN NORTH KOREA By Robert Huish Associate Professor, International Development Studies, Dalhousie University The Korean Children’s Union is not designed to nurture nor to inspire its members through friendship, camaraderie, or duty. It is meant to belittle, to intimidate, and to instill the belief that the supreme leader is all powerful. It rigorously instructs children that to be an individual is meaningless. No child is unique. Each one is just like the other. Replaceable, disposable, and ultimately? Worthless. Based on the testimony of numerous defectors, we know that North Korean children are told by the government to love the supreme leader more than their own parents. Mom and dad may be responsible for them day to day, but ultimately it is the leader who provides for them in every way. Sound cultish? It is. Juche, or “self reliance”, is North Korea’s official ideology meant to drive the nation towards true socialism. It is a deranged and maniacal cult of personality that convinces people not to think for themselves, but to think through the leader. Allons-y, Volume 3 | January 2019 23 It begins with nursery rhymes. There are two distinct kinds. The first gives fawning praise and boisterous credence to Kim Il Sung, the eternal leader of North Korea, along with his direct descendants Kim Jong Il, and Kim Jong Un. The second set of children’s songs are chalked full of lyrics about killing “Japanese dogs” and dismembering “American bastards”. -

Korea's Speciality Kaesong Koryo Insam

CONTENTS Δ Kim Jong Un Inspects Several Sectors ··································1 Δ Paduk with Time-honoured History ····································26 Δ Mt. Osong Tells ········································································4 Δ Performance Makes Popular Hit ········································28 Δ Jonsan Revolutionary Battle Site ·······································6 Δ Korea’s Speciality Δ Kimjongilia Exhibition held in China ···································8 Kaesong Koryo Insam ··················································30 Δ Pioneers on Sepho Tableland ·········································· 10 Δ National Day of Persons with Disabilities Marked ············32 Δ Various LED Lights Are Produced ·····································14 Δ Honey Bee “Doctor” in Hwangju ·········································34 Δ Renovated Sports Village on Chongchun Street ················16 Δ Koguryo Tomb with Murals Unearthed ···························35 Δ Koryo Ceramics Earn High Praise ···········································19 Δ Historical Relic Δ Village Appeared with the Construction Kwangbop Temple ·························································36 of Ryongnim Dam ······························································20 Δ Anti-“Government” Feelings Surge ·········································38 Δ Key to Victory ····································································22 Δ News Roundup ···································································40 Δ Young Scientist -

Historical Relations Between Poland and North Korea from 1948 to 1980*

International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 27, No. 1, 2018, 29−70. Historical Relations between Poland and North Korea from 1948 to 1980* Nicolas Levi** and Kyungyon Moon*** This article focuses on relations between Poland and North Korea from 1948 till 1980, focusing on places of remembrance of Poles in North Korea, and North Korean citizens in Poland. During this period, bilateral relations between these countries were very close due to their belonging to the same ideological movement. The article focuses on political, ideo- logical, cultural, and economic relations based on three historical phases of the Korean War (1950-1953), Post-Korean War (1953-1960) and distur- bance of Poland-North Korea relations (1960-1980). The paper argues that although Poland did make efforts to successfully foster mutual rela- tions, sometimes regardless of Polish interest, the behavior of DPRK authorities reduced the benefits Poland could gain from maintaining relations with this country. The DPRK focused on its interest and not on the interest of fraternal nations. This led to a negative image of the DPRK authorities among the Polish leadership and automatically to negative views concerning the DPRK population among Poles. Keywords: Asymmetry of relations, North Korea, Poland, Communism, Juche ideology * This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government [NRF-2016S1A3A2924968]; This research was supported by “Research Base Construction Fund Support Program” funded by Chonbuk National University in 2018. ** Assistant Professor, Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Science, First Author. *** Assistant Professor, Chonbuk National University, Corresponding Author. -

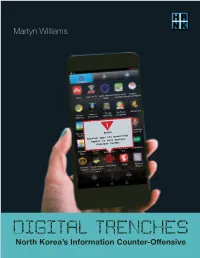

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres, -

Militaristic Propaganda in the DPRK the Heritage of Songun-Politics in the Rodong-Sinmun Under Kim Jong-Un

University of Twente Faculty of Behavioural, Management & Social Sciences 1st Supervisor: Dr. Minna van Gerven-Haanpaa Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Institut für Politikwissenschaft 2nd Supervisor: Björn Goldstein, M.A. Militaristic propaganda in the DPRK The heritage of Songun-Politics in the Rodong-Sinmun under Kim Jong-Un Julian Muhs Matr.- Nr.: 384990 B.A. & B.Sc Schorlemerstraße 4 StudentID; s1610325 Public Administration 48143 Münster (Westf.) (Special Emphasis on European Studies) 004915141901095 [email protected] Date: 21st of September.2015 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................................... 3 3.1. North Korean Ideology from Marxism-Leninism to Juche ........................................................... 3 3.2. Press Theory between Marxism-Leninism and Juche .................................................................. 8 3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 13 3.1. Selection of Articles .................................................................................................................... 17 4. Analysis: Military propaganda in the Rodong-Sinmun .................................................................. 19 4.1. Category-system