Volume 6, Number 2, Fall 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conserving Wildlife in African Landscapes Kenya’S Ewaso Ecosystem

Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press smithsonian contributions to zoology • number 632 Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press AConserving Chronology Wildlife of Middlein African Missouri Landscapes Plains Kenya’sVillage Ewaso SitesEcosystem Edited by NicholasBy Craig J. M. Georgiadis Johnson with contributions by Stanley A. Ahler, Herbert Haas, and Georges Bonani SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of “diffusing knowledge” was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: “It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge.” This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com- mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to History and Technology Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report on the research and collections of its various museums and bureaus. The Smithsonian Contributions Series are distributed via mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institu- tions throughout the world. Manuscripts submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press from authors with direct affilia- tion with the various Smithsonian museums or bureaus and are subject to peer review and review for compliance with manuscript preparation guidelines. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE A. PERSONAL DATA 1. 1. Name:(Underline Surname) Adetutu Deborah Aina-Pelemo 2. 2. Marital Status Married 3. Postal/Contact Address No. 21a Avenue, Citec Mborah Estate, Jabi District, Abuja-FCT; 4. E-mail address [email protected] Or aina- [email protected]) Skype Name: adetutuaina 5. Mobile Phone No.: +2348038397372; 6. Number and Ages of Children One- (1 year) 7. Name and Address of Spouse Mr. Victor B. Pelemo; 77, Sokoto Road, GLO Office, Gusau, Zamfara, Nigeria 8. Name and Address of Next of Kin Mr. Victor B. Pelemo; 77, Sokoto Road, GLO Office, Gusau, Zamfara, Nigeria 9. Nationality Nigerian 10. State of Origin Osun State B. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND 11 Academic Institutions Attended with Dates i) Sharda University 2015 – 2019 ii) University of Ilorin 2012 – 2014 iii) Nigerian Law School 2009 – 2010 iv) Olabisi Onabanjo University 2004 – 2009 v) Federal Government College, Ibillo, 1996 - June 2001 vi) Ola - Oluwa Nur./Pry School, Iju-Itaogboolu, 1989 – 1995 12 Academic and Professional Qualifications i) Doctor of Philosophy, (Ph.D. in Labour Relations & 2019 Industrial Law) ii) Master of Laws (Common Law) 2014 iii) Barrister at Laws (B.L) 2010 iv) Bachelor of Laws (LL.B) Second Class Honours 2009 13 Distinctions, Fellowships and Awards with Dates i) Resource Person: Selection of the best Researched Paper at the 3rd National Conference on Human Rights and Gender Justice. Knowledge Steez, at Indian Law Institute, New Delhi. June 2018 ii) Moot Judge: Preliminary Round on the occasion of 5th National Moot Court Competition of School of Law, IMS Unison University, Dehradum -- India. -

African Journal of Political Science and International Relations Volume 8 Number Number 2 6January, September 2014 2014 ISSN 19961993-08328233

African Journal of Political Science and International Relations Volume 8 Number Number 2 6January, September 2014 2014 ISSN 19961993-08328233 ABOUT AJPSIR The African Journal of Political Science and International Relations (AJPSIR) is published monthly (one volume per year) by Academic Journals. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations (AJPSIR) is an open access journal that publishes rigorous theoretical reasoning and advanced empirical research in all areas of the subjects. We welcome articles or proposals from all perspectives and on all subjects pertaining to Africa, Africa's relationship to the world, public policy, international relations, comparative politics, political methodology, political theory, political history and culture, global political economy, strategy and environment. The journal will also address developments within the discipline. Each issue will normally contain a mixture of peer-reviewed research articles, reviews or essays using a variety of methodologies and approaches. Contact Us Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJPSIR Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/ Editors Dr. Thomas Kwasi Tieku Dr. Aina, Ayandiji Daniel Faculty of Management and Social Sciences New College, University of Toronto Babcock University, Ilishan – Remo, Ogun State, 45 Willcocks Street, Rm 131, Nigeria. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Prof. F. J. Kolapo Dr. Mark Davidheiser History Department University of Guelph Nova Southeastern University 3301 College Avenue; SHSS/Maltz Building N1G 2W1Guelph, On Canada Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314 USA. Dr. Nonso Okafo Graduate Program in Criminal Justice Dr. Enayatollah Yazdani Department of Political Science Department of Sociology Norfolk State University Faculty of Administrative Sciences and Economics University of Isfahan Norfolk, Virginia 23504 Isfahan Iran. -

A Report on the Mapping Study of Peace & Security Engagement In

A Report on the Mapping Study of Peace & Security Engagement in African Tertiary Institutions Written by Funmi E. Vogt This project was funded through the support of the Carnegie Corporation About the African Leadership Centre In July 2008, King’s College London through the Conflict, Security and Development group (CSDG), established the African Leadership Centre (ALC). In June 2010, the ALC was officially launched in Nairobi, Kenya, as a joint initiative of King’s College London and the University of Nairobi. The ALC aims to build the next generation of scholars and analysts on peace, security and development. The idea of an African Leadership Centre was conceived to generate innovative ways to address some of the challenges faced on the African continent, by a new generation of “home‐grown” talent. The ALC provides mentoring to the next generation of African leaders and facilitates their participation in national, regional and international efforts to achieve transformative change in Africa, and is guided by the following principles: a) To foster African‐led ideas and processes of change b) To encourage diversity in terms of gender, region, class and beliefs c) To provide the right environment for independent thinking d) Recognition of youth agency e) Pursuit of excellence f) Integrity The African Leadership Centre mentors young Africans with the potential to lead innovative change in their communities, countries and across the continent. The Centre links academia and the real world of policy and practice, and aims to build a network of people who are committed to the issue of Peace and Security on the continent of Africa. -

Peer Reviewed Abstract Submitted to the College of Health Sciences, Osun State University Annual Scientific Conference, June 15-19, 2020

PEER REVIEWED ABSTRACT SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES, OSUN STATE UNIVERSITY ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE, JUNE 15-19, 2020. ABSTRACT - CHS/2020/01 Assessment of risk factors associated with drug resistant-tuberculosis among patients on dots treatment for tuberculosis in Ibadan, Oyo State *Akinleye, C.A.1, Onabule, A.2, Oyekale, A.O.3, Akindele, M.O.2, Babalola, O.J.4, Olarewaju, S.O.1 1Department of Community Medicine, Osun State University, Osogbo, Nigeria 2Department of Clinical Nursing University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria 3Department of Chemical Pathology Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Osogbo, Nigeria. 4Oyo state Tuberculosis and leprosy control unit. Ministry of Health. Secretariat, Ibadan, Nigeria *Corresponding author: Dr Callistus Akinleye (E-mail: [email protected]) Introduction: MDR-TB poses a significant challenge to global management of TB. Laboratories in many countries among which include Nigeria are unable to evaluate drug resistance, and clinical predictors of MDR-TB might help target suspected patients. Method: The study was a cross sectional study design. Multistage sampling technique was employed in the selection of 403 tuberculosis patients. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25. Level of significance was set at P<0.05. Results: Fifty three 53 (13.2%) of the total respondent had MDR-TB compare to national prevalence of 8% which is steeper among males 36(67.9%) (p>0.05). Education and Occupation shows a significant association with MDR-TB, (÷2=24.640, p = 0.007) and (÷2=14.416, p=0.006) respectively, smoking (r=0.074, p<0.05) and alcohol consumption (r=0.083, p>0.05) show no significant association with occurrence MDR-TB. -

Somalia's Judeao-Christian Heritage 3

Aram Somalia's Judeao-Christian Heritage 3 SOMALIA'S JUDEAO-CHRISTIAN HERITAGE: A PRELIMINARY SURVEY Ben I. Aram* INTRODUCTION The history of Christianity in Somalia is considered to be very brief and as such receives only cursory mention in many of the books surveying this subject for Africa. Furthermore, the story is often assumed to have begun just over a century ago, with the advent of modem Western mission activity. However, evidence from three directions sheds light on the pre Islamic Judeao-Christian influence: written records, archaeological data and vestiges of Judeao-Christian symbolism still extant within both traditional 1 Somali culture and closely related ethnic groups • Together such data indicates that both Judaism and Christianity preceded Islam to the lowland Horn of Africa In the introduction to his article on Nubian Christianity, Bowers (1985:3-4) bemoans the frequently held misconception that Christianity only came recently to Africa, exported from the West. He notes that this mistake is even made by some Christian scholars. He concludes: "The subtle impact of such an assumption within African Christianity must not be underestimated. Indeed it is vital to African Christian self-understanding to recognize that the Christian presence in Africa is almost as old as Christianity itself, that Christianity has been an integral feature of the continent's life for nearly two thousand years." *Ben I. Aram is the author's pen name. The author has been in ministry among Somalis since 1982, in somalia itself, and in Kenya and Ethiopia. 1 These are part of both the Lowland and Highland Eastern Cushitic language clusters such as Oromo, Afar, Hadiya, Sidamo, Kambata, Konso and Rendille. -

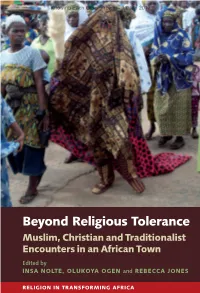

Beyondrt Book02.Indb 1 05/12/2016 10:25 Knowing Each Other Project - 11 Jan 2017

RELIGION IN TRANSFORMING AFRICA Knowing Each Other Project - 11 Jan 2017 Beyond Religious Tolerance Beyond ‘an important contribution to the ethnography of religion, peaceful coexistence and communal politics … a very readable and enjoyable book.’ Wale Adebanwi, University of California-Davis ‘a timely and refreshing addition to the growing literature on religious collaboration and coexistence in otherwise religiously divided societies across the world.’ Ebenezer Obadare, University of Kansas Since the end of the Cold War, and especially since 9/11, religion has become an increasingly important factor of personal and group identification. Based on an African case study, this book calls for new ways of thinking about diversity that go ‘beyond religious tolerance’. Focusing on the predominantly Muslim Yoruba town of Ede, the authors challenge the assumption that religious difference automatically leads to conflict: in south-west Nigeria, Muslims, Christians and traditionalists have co-existed largely peacefully since the early twentieth century. In some contexts, Ede’s citizens emphasise the importance and significance of religious difference, and the need for tolerance. But elsewhere they refer to religious boundaries in passing, or even celebrate and transcend religious divisions. Drawing on detailed ethnographic and historical research, survey work, oral histories and poetry by UK- and Nigeria- based researchers, the book examines how Ede’s citizens experience religious difference in their everyday lives. It examines the town’s royal history and relationship with the deity Sàngó, its old Islamic compounds and its Christian institutions, as well as marriage and family life across religious boundaries, to illustrate the multiplicity of religious practices in the life of the town and its citizens and to suggest an alternative approach to religious difference. -

Unai Members List August 2021

UNAI MEMBER LIST Updated 27 August 2021 COUNTRY NAME OF SCHOOL REGION Afghanistan Kateb University Asia and the Pacific Afghanistan Spinghar University Asia and the Pacific Albania Academy of Arts Europe and CIS Albania Epoka University Europe and CIS Albania Polytechnic University of Tirana Europe and CIS Algeria Centre Universitaire d'El Tarf Arab States Algeria Université 8 Mai 1945 Guelma Arab States Algeria Université Ferhat Abbas Arab States Algeria University of Mohamed Boudiaf M’Sila Arab States Antigua and Barbuda American University of Antigua College of Medicine Americas Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Facultad Regional Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Universidad Abierta Interamericana Americas Argentina Universidad Argentina de la Empresa Americas Argentina Universidad Católica de Salta Americas Argentina Universidad de Congreso Americas Argentina Universidad de La Punta Americas Argentina Universidad del CEMA Americas Argentina Universidad del Salvador Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cordoba Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de la Pampa Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Rosario Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de -

A Bayesian Test of the Lineage-Specificity of Word-Order

A Bayesian test of the lineage-specificity of word-order correlations Gerhard Jäger, Gwendolyn Berger, Isabella Boga, Thora Daneyko & Luana Vaduva Tübingen University DIP Colloquium Amsterdam January 25, 2018 Jäger et al. (Tübingen) Word-order Universals ALT2017 1 / 30 Introduction Introduction Jäger et al. (Tübingen) Word-order Universals ALT2017 2 / 30 Introduction Word order correlations Greenberg, Keenan, Lehmann etc.: general tendency for languages to be either consistently head-initial or consistently head-final alternative account (Dryer, Hawkins): phrases are consistently left- or consistently right-branching can be formalized as collection of implicative universals, such as With overwhelmingly greater than chance frequency, languages with normal SOV order are postpositional. (Greenberg’s Universal 4) both generativist and functional/historical explanations in the literature Jäger et al. (Tübingen) Word-order Universals ALT2017 3 / 30 Introduction Phylogenetic non-independence languages are phylogenetically structured if two closely related languages display the same pattern, these are not two independent data points ) we need to control for phylogenetic dependencies (from Dunn et al., 2011) Jäger et al. (Tübingen) Word-order Universals ALT2017 4 / 30 Introduction Phylogenetic non-independence Maslova (2000): “If the A-distribution for a given typology cannot be assumed to be stationary, a distributional universal cannot be discovered on the basis of purely synchronic statistical data.” “In this case, the only way to discover a distributional universal is to estimate transition probabilities and as it were to ‘predict’ the stationary distribution on the basis of the equations in (1).” Jäger et al. (Tübingen) Word-order Universals ALT2017 5 / 30 The phylogenetic comparative method The phylogenetic comparative method Jäger et al. -

1844 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 44

Kenya Past and Present Issue 44 Kenya Past and Present Editor Peta Meyer Editorial Board Marla Stone Kathy Vaughan Patricia Jentz Kenya Past and Present is a publication of the Kenya Museum Society, a not-for-profit organisation founded in 1971 to support and raise funds for the National Museums of Kenya. Correspondence should be addressed to: Kenya Museum Society, PO Box 40658, Nairobi 00100, Kenya. Email: [email protected] Website: www.KenyaMuseumSociety.org Statements of fact and opinion appearing in Kenya Past and Present are made on the responsibility of the author alone and do not imply the endorsement of the editor or publishers. Reproduction of the contents is permitted with acknowledgement given to its source. We encourage the contribution of articles, which may be sent to the editor at [email protected] No category exists for subscription to Kenya Past and Present; it is a benefit of membership in the Kenya Museum Society. Available back issues are for sale at the Society’s offices in the Nairobi National Museum and individual articles can be accessed online at the African Journal Archive: https://journals.co.za/content/collection/african-journal-archive/k Any organisation wishing to exchange journals should write to the Resource Centre Manager, National Museums of Kenya, PO Box 40658, Nairobi 00100, Kenya, or send an email to [email protected] Designed by Tara Consultants Ltd Printed by Kul Graphics Ltd ©Kenya Museum Society Nairobi, June 2017 Kenya Past and Present Issue 44, 2017 Contents The past year at KMS ..................................................................................... 3 Patricia Jentz The past year at the Museum ....................................................................... -

Pastoralism and Conflict Management in the Horn of Africa: a Case Study of the Borana in North Eastern Kenya

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI INSTITUTE OF DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES (IDIS) Pastoralism and Conflict Management in the Horn of Africa: A Case Study of the Borana in North Eastern Kenya FELIX W. WATAKILA R50/75924/2014 A Research Project Submitted in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Masters of Arts Degree in International Studies. 2011 5 DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been submitted for any Award in any other University. ……………………………. Date……………….…………..……… Felix W. Watakila This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as the assigned University Supervisor. …………………………….. Date…………………………… Dr. Kizito Sabala Lecturer, Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies (IDIS) University of Nairobi i DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this work to my dear family, my wife Jackline Khayesi Ligami and to our children Elizabeth Kakai Watakila and Charles Mukabi Watakila, for their support, patience and sacrifice during my study. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I acknowledge my supervisor Dr. Kizito Sabala for his guidance and input throughout this research study. I further wish to appreciate the committed leadership and direction of the college commandant Lt Gen J N Waweru and the entire faculty staff, for providing an enabling atmosphere during the course duration that enabled me to complete this thesis on time. I also give special thanks to the University of Nairobi lecturers, for their tireless efforts to equip me with the necessary tools for my study. I further wish to thank my fellow course participants of Course 17 of 2014/2015, for their constant support and encouragement. iii ABSTRACT Generally, the study is about pastoralism and conflict management in the Horn of Africa using Borana of Kenya as a case study. -

The Emerging National Culture of Kenya: Decolonizing Modernity

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 2 Number 2 Special Issue on Kenya and the Kenyan Article 8 Diaspora June 2010 The meE rging National Culture of Kenya: Decolonizing Modernity Olubayi Olubayi Rutgers University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the African Studies Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Olubayi, Olubayi (2010) "The meE rging National Culture of Kenya: Decolonizing Modernity," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 2 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol2/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Global Initiatives 2(2) (2007). pp. 222-237 The Emerging National Culture of Kenya: Decolonizing Modernity Olubayi Olubayi Abstract Kenya exists as a legitimate nation state that is recognized by the United Nations and by other countries. This paper is an exploration of, and a response to, the following two questions: "Is there a national culture ofKenya?" and "what is the relationship between the national culture ofKenya and the 50 ethnic cultures of Kenya?" The evidence indicates that a distinct national culture of Kenya has emerged and continues to grow stronger as it simultaneously borrows from, reorganizes, and lends to, the 50 ancient ethnic cultures of Kenya.