Newly Unsealed Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open the Trestle" Rally County Executive Doug Duncan Announces Support for the Trestle and the Trail by Wayne Phyillaier/CCCT Chair

HERESCENT Fall 1999 Vol X No. 4 Coalition Hosts "Open The Trestle" Rally County Executive Doug Duncan announces support for the trestle and the Trail By Wayne Phyillaier/CCCT Chair One of the best ways to build support and stewardship of the Capital Crescent Trail is to provide opportunities for trail users and local residents to experience trail advocacy in a personal way. On Saturday, October 23d, the Coalition for the Capital Crescent Trail did just that. Trail lovers from all around the metropolitan area participated in Coalition-sponsored hikes, both walking and biking, to the Rock Creek Park trestle for an "Open The Trestle" rally. Several Coalition Board members addressed the rally, and outlined why I repairing and opening the trestle for Trail use was essential for completing a first class interim trail to Silver Spring. Results of a Coalition sponsored I engineering design study were presented that show how the trestle can be rebuilt for Trail use at a t Dozrg Dz~ncanut rally fraction of the cost of building a new bridge. Joining rally participants was Montgomery County Executive, Mr. Doug Duncan, who spoke in support of completing the Trail. In a surprise announcement, Mr. Duncan pledged to put funding to rebuild the trestle in the upcoming FY 2001-2002 budget. He challenged trail supporters to do their part and get the support of the five County Council members needed to pass the budget. Mr. Duncan's pledge of support is a very welcome event, and allows the Coalition to focus its advocacy for the trestle on the Montgomery County council. -

Marylandinfluencers

MarylandInfluencers f there was one place where the Democratic Party could take sol- ace on Election Day 2010, it was Maryland, a rock that broke part Iof the red tide sweeping the country. In a year where Republi- cans hoped to make gains across the board, Democrats proved their dominance in the biggest races, holding the governor’s mansion in a landslide, losing just a handful of seats in the state House of Delegates, and actually gaining ground in the state Senate. Any doubts about how deep blue Maryland is—particularly within the state’s heavily populated central corridor—were surely dissipated. Yet the next few years will be pivotal for both parties. Age and term limits are taking their toll on veteran officeholders, opening up op- portunities for ambitious Republicans and Democrats alike to make their mark. The blood sport of redistricting will play out as well. Here is our list of the Democrats and Republicans who are helping to make the decisions and start the important political conversations today in the Chesapeake Bay State—as well as some likely to play a bigger role in the future. Top 10 Republicans Robert L. Ehrlich, Jr. GOP voters for representatives who her husband. She may be ending her The only Republican governor in Mary- are fiscally conservative and socially conservative talk radio show on WBAL land since the 1960s was dealt a huge moderate. 1090-AM in Baltimore—a thorn in blow in November when his rematch Democratic sides for years—but she will with O’Malley ended in a landslide loss. -

Basin Bridge Board of Inquiry Representation by Nina Arron, Submitter 103484

Basin Bridge Board of Inquiry Representation by Nina Arron, submitter 103484 1. I am an urban planner and former Wellington resident. I now live in New Rochelle, New York. 2. I view the proposed flyover as an outdated 20th Century solution to something that I do not believe is even a problem. We are in a time of transition to more sustainable modes of transport and improved walkability, cycling and public transport options over designing solely for the private car. 3. This transition is driven by the desire for a more sustainable transport system, but it is also driven by evidence from many countries that there is a mismatch between transport agencies’ modelling, which assumes that the use of cars will continue to grow on a “business as usual” basis, and a reality that is rapidly undermining that assumption. 4. I have provided an Appendix of supplementary material. This consists of an article which I wrote for Wellington online news site Scoop entitled “Transportation in the 21st Century: The Modelling/Reality Gap”, published on 11 November 2013. Together with this article, I have included the text of three references linked to in the article, showing recent examples from the US, Canada and Australia of transport projects that have failed to meet or even come close to their stated goals because transport modellers projected continued traffic growth which failed to eventuate. 5. This phenomenon can also be observed in New Zealand, as the final article I have supplied, “Kiwi Teens Turn Off Driving”, shows. To quote from the article: A worldwide trend known as "driving ambivalence" has hit young people in New Zealand. -

Potomacpotomac Page 8

Wellbeing PotomacPotomac Page 8 Weathering Another Storm News, Page 5 Real Estate 6 Real Estate ❖ Sports 7 ❖ Calendar, Page 11 ❖ Classified, Page 10 Classified, Slates Set for Primary Elections A pileated wood- News, Page 2 pecker forages midst Monday’s snowstorm in a Potomac backyard. anac Why Care about Ten Mile Creek? Opinion, Page 4 State Basketball Playoffs Delayed Sports, Page 7 Photo Mary Kimm/The Alm Photo online at potomacalmanac.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.comMarch 5-11, 2014 Potomac Almanac ❖ March 5-11, 2014 ❖ 1 News June primary will likely settle many Slates Set for Primary Elections county races. Compiled by Ken Moore Green Party candidate Tim Willard. The Almanac Board of Education he filing deadline for candidates While the Board of Education also has at- who plan to run for their party’s General Assembly: Potomac is large and district members, it works differ- nominations was Feb. 25, and divided between District 15 ently than for County Council. While can- T and 16 with one state senator many races for local and state didates for Board of Education in a given offices are now set. The Primary Election is and three delegates per dis- district must live inside the boundaries of scheduled for June 24. Currently there are trict. the district, all voters in the county will vote no elected Republicans from Montgomery to choose members for each district and the County, so in many cases the winners of the County Coun- at-large member. Democratic primary on June 24 will be the cil, District 1 Members of the Board of Education serve likely winner in November. -

Remarks by Montgomery County Council President Steve Silverman at Committee for Montgomery Annual Breakfast December 5, 2001

Remarks by Montgomery County Council President Steve Silverman at Committee for Montgomery Annual Breakfast December 5, 2001 Good morning. I want to thank the Committee for Montgomery for inviting me to talk with all of you this morning. Last year’s General Assembly session was a great success for Montgomery County. Much of the credit goes to our delegates, led by Kumar Barve; our senators, led by Ida Ruben; and our county executive Doug Duncan. Their hard work and team work paid off. But many of you in this room were also important partners in our county’s success. There are too many examples to mention, but having said that, I’m going to mention some anyway. There’s Gene Counihan, who is helping to build a new Olney Theatre and helping to better our business community through the Chamber of Commerce. There is Sally Sternbach who must have been incredibly far sighted to leave AT&T before the telecom meltdown and transferred her energies to her community in Silver Spring and to education as president of the Blair High School PTSA. There is Fernando Cruz-Villalba who has pressed tirelessly for better health care and other needs of the Hispanic community. They and other members of Committee for Montgomery are leaders in so many different areas of this county. And yet you all take time out of your busy professional and community lives to come together on Montgomery County’s behalf to make sure our voice is heard in Annapolis. You’re an incredible resource for this county and this is my one time to be able to thank you publicly! Now more than ever, we will need your voice in Annapolis. -

"Federation Corner" Column the Montgomery Sentinel - April 10, 2014

"Federation Corner" column The Montgomery Sentinel - April 10, 2014 Season of campaign promises upon us again by Jim Humphrey Chair, MCCF Planning & Land Use Committee June 24, Primary Election Day, is approximately ten weeks away. And the chorus of promises resonating from the campaign trail is beginning to rise in volume, with incumbents and wannabes fighting for attention from Montgomery County voters. So this might be a good time for county residents to recall a key issue that faced us four years ago, and one which we still face today--the impact of new construction on worsening traffic congestion. Polls conducted by the Washington Post and the Baltimore Sun earlier in 2009 had showed growth and traffic congestion to be leading concerns across the state, but particularly in Montgomery County. County Executive incumbent Isiah Leggett said he would push to reinstate "policy area review," which used formulas to determine whether communities were too overwhelmed by traffic to accommodate new development. The developer friendly majority of a previous County Council, the self-labeled End Gridlock slate, had eliminated the process in 2003, with backing from former County Executive Doug Duncan. In November 2007 the members of the last Council instated a new policy area transportation test. However, Leggett objected to it saying it "provides results that do not accurately reflect actual transportation capacity, is difficult to understand and thus is not transparent to County residents," a sentiment echoed by many civic activists. It took the County Executive until March of 2010--two and a half years--to transmit to the Council his recommendation for an improved process. -

Washington, D.C., Metropolitics Myron Orfield University of Minnesota Law School

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Studies Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity 1998 Washington, D.C., Metropolitics Myron Orfield University of Minnesota Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.umn.edu/imo_studies Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Myron Orfield, Washington, D.C., Metropolitics (1998). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington Metropolitics: A Regional Agenda for Community and Stability Myron Orfield Metropolitan Area Research Corporation A Report to the Brookings Institution July 1999 This report was a project of the Metropolitan Area Research Corporation (MARC). It was made possible with the support of the Prince Charitable Trusts, The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, The Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer Foundation, The Philip L. Graham Fund, Robert Kogod, and W. Russell Ramsey. The Metropolitan Area Research Corporation would like to thank the following people for their written comments which greatly improved the final report: Jennifer Bradley, The Brookings Institution; Lee Epstein, Chesapeake Bay Foundation; Bruce Katz, The Brookings Institution; Robert Lang, The Fannie Mae Foundation; and Amy Liu, The Brookings Institution. Input from the following people through meetings and personal interviews was also very -

THE MONTGOMERY COUNTY SENTINEL AUGUST 17, 2017 EFLECTIONS the Montgomery County Sentinel, Published Weekly by Berlyn Inc

2015, 2016 MDDC News Organization of the Year! Celebrating 161 years of service! Vol. 163, No. 8 • 50¢ SINCE 1855 August 17 - August 23, 2017 TODAY’S GAS Local Man Leads Alt-Right PRICE Matthew Heimbach grew up in MoCo and helped organize the march in Charlottesville $2.36 per gallon Last Week Raised locally, Heimbach at- Monocacy elementary school. They surprised me,” Said Dr. John C. $2.38 per gallon By Matt Hooke @matth255 tended Poolesville High School have both disowned Heimbach for Thompson one of Heimbach’s for- where he said he attempted to create his white nationalist views. mer professors at Montgomery Col- A month ago Matthew Heimbach, the Chair- a white student group. “My family due to my politics lege. $2.28per gallon man of the Traditionalist Workers “I got several hundred students has totally cut me off. They haven’t “He struck me as someone who A year ago Party (a White Nationalist organiza- to sign on to my paper to do it. The seen my two sons, and I haven’t spo- cowered easily. However, he was hit- $2.13 per gallon tion), watched as anti-fascist principal trashed it. I emailed every ken to them in many years,” said He- ting a woman so maybe he felt counter-protesters showered his fol- teacher to get a sponsor none of them imbach. “They didn’t raise me to brave,” the history professor added. AVERAGE PRICE PER GALLON OF lowers in bleach and urine in Char- UNLEADED REGULAR GAS IN responded; it must have been an ad- think like this. -

Preparing for Light Rail in the Purple Line Corridor

Preparing for Light Rail in the Purple Line Corridor By: Richard Duckworth Advisor: Dr. Alex Karner Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 CAPITALIZATION OF PUBLIC INVESTMENT INTO PRIVATE PROPERTY VALUES 3 EMPIRICAL STUDY 4 TIMELINE OF PURPLE LINE PLANNING 6 STUDY OF PURPLE LINE EFFECTS 9 HOME SALE DATA 9 METHODOLOGY 11 OTHER DATA SOURCES 12 FINDINGS 13 ENTIRE STUDY AREA 13 PRE-CONSTRUCTION EFFECTS ON HOME PRICES 16 EAST ZONE 17 PRE-CONSTRUCTION EFFECTS ON HOME PRICES IN THE EAST ZONE 18 UNIVERSITY BOULEVARD ZONE 19 PRE-CONSTRUCTION EFFECTS ON HOME PRICES IN THE UNIVERSITY BOULEVARD ZONE 21 SILVER SPRING ZONE 22 PRE-CONSTRUCTION EFFECTS ON HOME PRICES IN THE SILVER SPRING ZONE 23 WEST ZONE 24 PRE-CONSTRUCTION EFFECTS ON HOME PRICES IN THE WEST ZONE 26 SUMMARY 26 CONCLUSION 27 REFERENCES 28 APPENDIX A: SINGLE-FAMILY HOME SALES DATASET 31 APPENDIX B: FULL REGRESSION RESULTS 32 1 Introduction The Purple Line is a proposed light rail transit line that will run 16 miles through Maryland’s inner suburbs of Washington, DC. A team led by Fluor Corporation, in a public-private partnership with the State of Maryland, will build seventeen new rail stations and four stops at existing Metrorail stations. The new transit corridor stretches sixteen miles from New Carrollton in Prince George’s County to Bethesda in Montgomery County, with the new stations split evenly between the two counties. In 2014, the Federal Transit Administration recommended $900 million in federal grants for the project. Prince George’s and Montgomery Counties are expected to contribute about $330 million, and the state estimates that it will spend $3.3 billion over 36 years on the Purple Line (Office of Governor Larry Hogan 2016). -

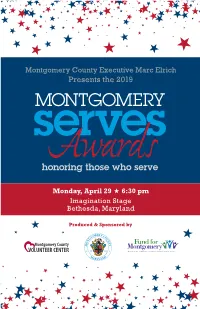

2019 Montgomery Serves Awards Program

Montgomery County Executive Marc Elrich Presents the 2019 Monday, April 29 H 6:30 pm Imagination Stage Bethesda, Maryland Produced & Sponsored by Sponsored Events for 2018-2019 10 Sunday, October 21, 2018 COMMUNITY Service Week October 21-28, 2018 MLK Day of Service MLK Tribute and Celebration Monday, January 21, 2019 April 29, 2019 For more information go to MontgomeryServes.org 2019 MONTGOMERY SERVES AWARDS — 1 Awards Program WELCOME AND RECOGNITION OF ELECTED OFFICIALS Emcee Andrea Roane REMARKS County Executive Marc Elrich VOLUNTEER OF THE YEAR AWARD Awarded to Amy Yontef-McGrath Presented by Cheryl Kagan, Maryland State Senator (District 17) YOUTH VOLUNTEER OF THE YEAR AWARD Awarded to Dhruv Pai Presented by Shella Cherry, Coordinator of Student Leadership & Volunteers, Montgomery County Public Schools VOLUNTEER GROUP OF THE YEAR AWARD Awarded to Volunteers of KindWorks Presented by Sara Love, Maryland State Delegate (District 16), and Rob Scheer, Founder of Comfort Cases BUSINESS VOLUNTEER OF THE YEAR AWARD Awarded to Hugo Salon Presented by Joshua Bokee of Comcast NEAL POTTER PATH OF ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Awarded to Karen Bashir and Jacquette Frazier Presented by Margaret Foster of The Beacon Newspapers and County Councilmember Sidney Katz ROSCOE R. NIX DISTINGUISHED COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP AWARD Award Introduction by Veretta Nix and Susan Nix-Webster Awarded to Charlotte Coffield, Isiah Leggett, and David Rodich Presented by County Executive Elrich, joined by Veretta Nix, Susan Nix-Webster, and Marcus Boyd CONCLUSION Honorees to stage -

202-234-4433 Neal R. Gross & Co., Inc. Page 1 MARYLAND

Page 1 MARYLAND-NATIONAL CAPITAL PARK AND PLANNING COMMISSION + + + + + MONTGOMERY COUNTY PLANNING BOARD + + + + + COUNTYWIDE TRANSIT CORRIDORS FUNCTIONAL MASTER PLAN PUBLIC HEARING + + + + + THURSDAY, MAY 16, 2013 + + + + + The Montgomery County Planning Board met in the Montgomery County Planning Department Auditorium, Montgomery Regional Office Building, 8787 Georgia Avenue, Silver Spring, Maryland, at 6:00 p.m., Fran‡oise Carrier, Planning Board Chair, presiding. PRESENT FRAN€OISE CARRIER, Planning Board Chair, The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission CASEY ANDERSON, Planning Board Member and Commissioner NORMAN DREYFUSS, Planning Board Member and Commissioner AMY PRESLEY, Planning Board Member and Commissioner ALSO PRESENT LARRY COLE, Functional Planning and Policy Division DAVID ANSPACHER, Functional Planning and Policy Division MARY DOLAN, Functional Planning and Policy Division Neal R. Gross & Co., Inc. 202-234-4433 Page 2 T-A-B-L-E O-F C-O-N-T-E-N-T-S Opening Statement Larry Cole . .4 Testimony Dan Reed . .8 Amy Donin. 11 Theodore Van Houten. 15 Stewart Schwartz . 17 Nancy Ables. 23 Robert Dyer. 29 Richard Levine . 32 Michele Riley. 37 Christine Slater . 44 Harriet Quinn. 47 James Williamson . 52 Ethan Goffman. 56 Drew Morrison . 62 Fred Schultz . 65 Daniel Wilhelm . 70 David Anderson . 74 Clarence Steinberg . 76 Harold McDougall . 79 Marie Park . 85 Heather Brutz. 93 Tony Hausner . 95 Barbara Ditzler. 97 Eileen Finnegan. 99 Jonathan Wellemeyer. .104 Mary Ann Nyamweya. .107 Elaine Akst. .111 Virginia Bigger. .118 Freda Mitchem. .122 Livia Nicolescu . .128 Elizabeth Ewing. .131 Christopher Bradbury . .135 Robert Faul-Zeitler. .139 K. Travis Ballie . .142 James Russ . .145 James Zepp . .149 Brian Ditzler. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 18-726 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- LINDA H. LAMONE, et al., Appellants, v. O. JOHN BENISEK, et al., Appellees. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Appeal From The United States District Court For The District Of Maryland --------------------------------- --------------------------------- JOINT APPENDIX VOLUME II OF V (JA351 – JA611) --------------------------------- --------------------------------- MICHAEL B. KIMBERLY STEVEN M. SULLIVAN MAYER BROWN LLP Solicitor General 1999 K Street, N.W. 200 Saint Paul Place, Washington, DC 20006 20th Floor (202) 263-3127 Baltimore, Maryland 21202 mkimberly@ (410) 576-6325 mayerbrown.com [email protected] Counsel for Appellees Counsel for Appellants ================================================================ Appeal Docketed Dec. 6, 2018 Jurisdiction Postponed Jan. 4, 2019 ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume I Relevant Docket Entries* ............................................. 1 Exhibits to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment Deposition of Governor Martin O’Malley (Exhibit A, Dkt. 177-3; May 31, 2017) .................... 31 Deposition of Eric Hawkins (Exhibit B, Dkt. 177-4; May 31, 2017) .................... 90 Deposition of Jeanne D. Hitchcock (Exhibit F, Dkt. 177-8; May 31, 2017)