Preparing for Light Rail in the Purple Line Corridor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon's HQ2 Decision

RESEARCH JULY 2019 AMAZON’S HQ2: AN UPDATE ON ITS IMPACT ON THE WASHINGTON COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE MARKET AMAZON HAS ARRIVED PROJECT’S PUBLIC COST AND INCENTIVES More than seven months after announcing its decision to locate one half of its “HQ2” in National Landing, Amazon’s plans for its new campus are • Amazon will receive $550 million in workforce cash grants coming into focus. Amazon has signed leases at four buildings in from the Commonwealth of Virginia for the creation of National Landing totaling approximately 585,000 square feet. Amazon 25,000 new jobs. Additionally, Amazon can receive up to has moved into 47,512 square feet at 2345 Crystal Drive as it quickly $200 million in grants if it delivers on an additional 12,850 begins its hiring process for HQ2, and will occupy 88,000 square feet at jobs beyond the initial requirement. 241 18th Street South, 191,000 square feet at 1800 South Bell Street and 258,000 square feet at 1770 Crystal Drive as renovations at each location • Amazon will receive a cash grant of $23 million from finish. Working with JBG Smith, the largest property owner in National Arlington County for the incremental growth of an existing Landing and Amazon’s development partner, property manager and retail local Transient Occupancy Tax over the next 15 years. leasing agent, Amazon has begun to build out its workforce. Amazon is investing upwards of $95 million in tenant renovations. Notably, 1770 • The Commonwealth of Virginia has pledged $250 million Crystal Drive, where it will occupy the entirety of the 258,000 square foot towards Virginia Tech’s $1 billion investment in a new building, will make up a majority of the renovations, accounting for $80 campus proximate to Amazon’s new headquarters, which million of the total amount. -

![[Title Over Two Lines (Shift+Enter to Break Line)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4038/title-over-two-lines-shift-enter-to-break-line-134038.webp)

[Title Over Two Lines (Shift+Enter to Break Line)]

BUS TRANSFORMATION PROJECT White Paper #2: Strategic Considerations October 2018 DRAFT: For discussion purposes 1 1 I• Purpose of White Paper II• Vision & goals for bus as voiced by stakeholders III• Key definitions IV• Strategic considerations Table of V• Deep-dive chapters to support each strategic consideration Contents 1. What is the role of Buses in the region? 2. Level of regional commitment to speeding up Buses? 3. Regional governance / delivery model for bus? 4. What business should Metrobus be in? 5. What services should Metrobus operate? 6. How should Metrobus operate? VI• Appendix: Elasticity of demand for bus 2 DRAFT: For discussion purposes I. Purpose of White Paper 3 DRAFT: For discussion purposes Purpose of White Paper 1. Present a set of strategic 2. Provide supporting analyses 3. Enable the Executive considerations for regional relevant to each consideration Steering Committee (ESC) to bus transformation in a neutral manner set a strategic direction for bus in the region 4 DRAFT: For discussion purposes This paper is a thought piece; it is intended to serve as a starting point for discussion and a means to frame the ensuing debate 1. Present a The strategic considerations in this paper are not an set of strategic exhaustive list of all decisions to be made during this considerations process; they are a set of high-level choices for the Bus Transformation Project to consider at this phase of for regional strategy development bus transformation Decisions on each of these considerations will require trade-offs to be continually assessed throughout this effort 5 DRAFT: For discussion purposes Each strategic consideration in the paper is 2. -

Hearing from You Michael S

Robert L. Ehrlich, Jr. CONTACT US: Governor Hearing From You Michael S. Steele For further information about this project, please contact: Lt. Governor Fall 2004 Open Houses Lorenzo Bryant, Project Manager En Español: Jose M. Vazquéz Robert L. Flanagan Maryland Transit Administration Maryland Transit Administration MDOT Secretary 6 Saint Paul Street, 9th Floor 8720 Georgia Avenue, Suite 904 Plan to Attend Almost 300 people attended seven Red Line Open Houses Silver Spring, MD 20910 held between October 26 and November 9, 2004. At the Baltimore, MD 21202 Upcoming Public Open Open Houses, participants received updates on the status Lisa L. Dickerson (301) 565-9665 of the project, provided input, and received information on MTA Acting Administrator Telephone: 410-767-3754 Houses on the Red Line alternatives under study. The Open Houses were advertised in a project mailer and the website, as well as local newspapers. 410-539-3497 TTY The Maryland Transit Administration (buildings, historic districts, archaeological Fliers were also distributed to locations along the Red Line (MTA), in cooperation with Baltimore City, or cultural sites) that are eligible for the corridor. Materials presented at the Open Houses can Email: [email protected] | [email protected] Baltimore County, and federal and state National Register of Historic Places. If be viewed by logging on to the project website, resource agencies, will be preparing a you are interested in participating in the www.baltimoreregiontransitplan.com. Website: www.baltimoreregiontransitplan.com Draft Environmental Impact Statement Section 106-Public Involvement process, (DEIS) for the Red Line Study. preservation specialists will be available at Major themes from the Open House comments received Alternate formats of Red Line information can be provided upon request. -

Open the Trestle" Rally County Executive Doug Duncan Announces Support for the Trestle and the Trail by Wayne Phyillaier/CCCT Chair

HERESCENT Fall 1999 Vol X No. 4 Coalition Hosts "Open The Trestle" Rally County Executive Doug Duncan announces support for the trestle and the Trail By Wayne Phyillaier/CCCT Chair One of the best ways to build support and stewardship of the Capital Crescent Trail is to provide opportunities for trail users and local residents to experience trail advocacy in a personal way. On Saturday, October 23d, the Coalition for the Capital Crescent Trail did just that. Trail lovers from all around the metropolitan area participated in Coalition-sponsored hikes, both walking and biking, to the Rock Creek Park trestle for an "Open The Trestle" rally. Several Coalition Board members addressed the rally, and outlined why I repairing and opening the trestle for Trail use was essential for completing a first class interim trail to Silver Spring. Results of a Coalition sponsored I engineering design study were presented that show how the trestle can be rebuilt for Trail use at a t Dozrg Dz~ncanut rally fraction of the cost of building a new bridge. Joining rally participants was Montgomery County Executive, Mr. Doug Duncan, who spoke in support of completing the Trail. In a surprise announcement, Mr. Duncan pledged to put funding to rebuild the trestle in the upcoming FY 2001-2002 budget. He challenged trail supporters to do their part and get the support of the five County Council members needed to pass the budget. Mr. Duncan's pledge of support is a very welcome event, and allows the Coalition to focus its advocacy for the trestle on the Montgomery County council. -

Making Tracks the Case for Building a 21St Century Public Transportation Network in Maryland

Making Tracks The Case for Building a 21st Century Public Transportation Network in Maryland Maryland PIRG Foundation Making Tracks The Case for Building a 21st Century Public Transportation Network in Maryland Maryland PIRG Foundation Sarah Payne, Frontier Group Elizabeth Ridlington, Frontier Group Kristi Horvath, Maryland PIRG Foundation Johanna Neumann, Maryland PIRG Foundation March 2009 Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank Eric Christensen of the Maryland Transit Administration and Richard Chambers, Esq., board member of the Transit Riders Action Council of Metro- politan Baltimore, for their review of this report. The authors would also like to thank Tony Dutzik, Travis Madsen and Susan Rakov of Frontier Group for their editorial assistance. The generous financial support of the Rockefeller Foundation, Surdna Foundation, and Wallace Global Foundation made this report possible. The authors bear responsibility for any factual errors. The recommendations are those of Maryland PIRG Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. © 2009 Maryland PIRG Foundation With public debate around important issues often dominated by special interests pursuing their own narrow agendas, Maryland PIRG Foundation offers an independent voice that works on behalf of the public interest. Maryland PIRG Foundation, a 501(c)(3) organiza- tion, works to protect consumers and promote good government. We investigate problems, craft solutions, educate the public, and offer Maryland residents meaningful opportunities for civic participation. For more information about Maryland PIRG Foundation or for additional copies of this report, please visit www.MarylandPIRG.org. Frontier Group conducts independent research and policy analysis to support a cleaner, healthier and more democratic society. -

Approved Fiscal 2008 Annual Budget

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Serving the National Capital Region Approved Fiscal 2008 Annual Budget Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Approved Fiscal 2008 Annual Budget Serving the National Capital Region Table of Contents Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Approved Fiscal 2008 Annual Budget Serving the National Capital Region Table of Contents Table of Contents General Manager’s Letter......................................................................................3 Chapter 1. Introduction to Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority...............................................................................5 Metro Profile ...............................................................................................5 Metro’s Strategic Plan ................................................................................6 Metro Board of Directors and Agency Oversight ........................................7 Organization Chart .....................................................................................9 How to Contact Metro...............................................................................10 Chapter 2. Budget Summary..............................................................................13 Operating Budget .....................................................................................16 Capital Budget..........................................................................................17 Reimbursable Projects .............................................................................18 -

Marylandinfluencers

MarylandInfluencers f there was one place where the Democratic Party could take sol- ace on Election Day 2010, it was Maryland, a rock that broke part Iof the red tide sweeping the country. In a year where Republi- cans hoped to make gains across the board, Democrats proved their dominance in the biggest races, holding the governor’s mansion in a landslide, losing just a handful of seats in the state House of Delegates, and actually gaining ground in the state Senate. Any doubts about how deep blue Maryland is—particularly within the state’s heavily populated central corridor—were surely dissipated. Yet the next few years will be pivotal for both parties. Age and term limits are taking their toll on veteran officeholders, opening up op- portunities for ambitious Republicans and Democrats alike to make their mark. The blood sport of redistricting will play out as well. Here is our list of the Democrats and Republicans who are helping to make the decisions and start the important political conversations today in the Chesapeake Bay State—as well as some likely to play a bigger role in the future. Top 10 Republicans Robert L. Ehrlich, Jr. GOP voters for representatives who her husband. She may be ending her The only Republican governor in Mary- are fiscally conservative and socially conservative talk radio show on WBAL land since the 1960s was dealt a huge moderate. 1090-AM in Baltimore—a thorn in blow in November when his rematch Democratic sides for years—but she will with O’Malley ended in a landslide loss. -

A. Purple Line Light Rail, Mandatory Referral No

MONTGOMERY COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT THE MARYLAND-NATIONAL CAPITAL PARK AND PLANNING COMMISSION MCPB Item No. 2 Date: 03/20/14 A. Purple Line Light Rail, Mandatory Referral No. MR2014033 B. Bethesda Metro Station South Entrance, Mandatory Referral No. MR2014034, CIP Project 500929 C. Capital Crescent Trail, Mandatory Referral No. MR2014035, CIP Project 501316 D. Silver Spring Green Trail, Mandatory Referral No. MR2014036, CIP Project 509975 David Anspacher, Planner/Coordinator, [email protected], (301) 495-2191 Mary Dolan, Chief, [email protected], (301) 495-4552 Tom Autrey, Supervisor, [email protected], (301) 495-4533 Robert Kronenberg, Chief, [email protected], (301) 495-2187 Marc DeOcampo, Supervisor, [email protected], (301) 495-4556 Elza Hisel-McCoy, Planner/Coordinator, [email protected], (301) 495-2115 Tina Schneider, Senior Planner, [email protected], (301) 495-2101 Mike Riley, Deputy Director (Parks), [email protected], (301) 495-2500 John Hench, Division Chief, [email protected], (301) 650-4364 Brooke Farquhar, Section Chief, [email protected], (301) 650-4388 Chuck Kines, Park Planner/Coordinator, [email protected], (301) 495-2184 Mitra Pedoeem, Division Chief, [email protected], (301) 495-2554 Andy Frank, Section Chief, [email protected], (301) 650-2886 Jai Cole, Natural Resources Manager, [email protected], (301) 650-4366 Completed: 03/13/2014 Jai Cole, Natural Resources Manager, [email protected], (301) 650-XXXX Description The subject of this staff report is four mandatory referrals for the Purple Line (the portion in Montgomery County only), the Bethesda Metro Station South Entrance, an extension of the Capital Crescent Trail, and an extension of the Silver Spring Green Trail. -

MDOT MTA Purple Line Celebrates Winners of Elementary School Art Contest First-Place Selections to Be Displayed on Banners Along 16-Mile Purple Line Corridor

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACTS: Gary Witherspoon Brittany Marshall Office: 240-825-4629 Office: 410-767-8367 Cell: 443-801-4318 Cell: 443-970-0424 [email protected] [email protected] MDOT MTA Purple Line Celebrates Winners of Elementary School Art Contest First-Place Selections to be Displayed on Banners Along 16-Mile Purple Line Corridor RIVERDALE, MD (January 21, 2020) – Students from four elementary schools who turned images of the Purple Line rail project into award-winning art will have their work reproduced on banners displayed at project sites near their schools, the Maryland Department of Transportation Maryland Transit Administration (MDOT MTA) announced. “There are many talented, young artists in Prince George’s and Montgomery counties, and it’s exciting to see the project through their eyes,” said Jeff Ensor, director of the $5.6 billion Purple Line project for MDOT MTA. “It was difficult to select the winners because of the quality of all the entries.” This past fall, third graders from seven elementary schools along the Purple Line’s 16-mile corridor were invited to participate in the art contest. Students were asked to draw either a colorful picture of themselves and their families on the light rail or what they saw during Purple Line construction. Four schools took part and produced 140 pieces of art. Purple Line staff reviewed and selected the first-place artwork, one from each of the schools: http://bit.ly/38og1Y0. Glenridge, Langley Park-McCormick, Riverdale and Woodlin elementary schools participated in the contest. Lesli Leath, a senior community liaison with the Purple Line project and contest organizer, said the winners were selected based on “originality, vibrancy and authenticity.” “Clearly, there’s real artistic talent in schools along the Purple Line corridor,” she said. -

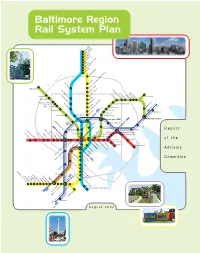

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Accessible Transportation Options for People with Disabilities and Senior Citizens

Accessible Transportation Options for People with Disabilities and Senior Citizens In the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area JANUARY 2017 Transfer Station Station Features Red Line • Glenmont / Shady Grove Bus to Airport System Orange Line • New Carrollton / Vienna Parking Station Legend Blue Line • Franconia-Springfield / Largo Town Center in Service Map Hospital Under Construction Green Line • Branch Ave / Greenbelt Airport Full-Time Service wmata.com Yellow Line • Huntington / Fort Totten Customer Information Service: 202-637-7000 Connecting Rail Systems Rush-Only Service: Monday-Friday Silver Line • Wiehle-Reston East / Largo Town Center TTY Phone: 202-962-2033 6:30am - 9:00am 3:30pm - 6:00pm Metro Transit Police: 202-962-2121 Glenmont Wheaton Montgomery Co Prince George’s Co Shady Grove Forest Glen Rockville Silver Spring Twinbrook B30 to Greenbelt BWI White Flint Montgomery Co District of Columbia College Park-U of Md Grosvenor - Strathmore Georgia Ave-Petworth Takoma Prince George’s Plaza Medical Center West Hyattsville Bethesda Fort Totten Friendship Heights Tenleytown-AU Prince George’s Co Van Ness-UDC District of Columbia Cleveland Park Columbia Heights Woodley Park Zoo/Adams Morgan U St Brookland-CUA African-Amer Civil Dupont Circle War Mem’l/Cardozo Farragut North Shaw-Howard U Rhode Island Ave Brentwood Wiehle-Reston East Spring Hill McPherson Mt Vernon Sq NoMa-Gallaudet U New Carrollton Sq 7th St-Convention Center Greensboro Fairfax Co Landover Arlington Co Tysons Corner Gallery Place Union Station Chinatown Cheverly 5A to -

Newly Unsealed Report

Case 8:18-cv-03821-TDC Document 468-1 Filed 03/05/21 Page 1 of 116 Expert Report Prepared By J. Thomas Manger In Hispanic National Law Enforcement Assoc. NCR et al. v. Prince George’s County et al., United States District Court District of Maryland Civil Action No.: 8:18-cv-03821-TDC 1 CONFIDENTIAL Case 8:18-cv-03821-TDC Document 468-1 Filed 03/05/21 Page 2 of 116 TABLE OF CONTENTS Experience ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope of Analysis ............................................................................................................................. 7 Materials Reviewed ........................................................................................................................ 7 Summary of Conclusions ................................................................................................................. 8 Landscape of Policing in the Washington D.C. Metropolitan Area .............................................. 10 A. Recruitment ................................................................................................................ 11 B. Background on Prince George’s County Police Department ...................................... 12 Analysis and Opinions ................................................................................................................... 14 PART 1. INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL EEO COMPLAINT PROCEDURES ....................................... 14 A. Prince George’s