Making Tracks the Case for Building a 21St Century Public Transportation Network in Maryland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearing from You Michael S

Robert L. Ehrlich, Jr. CONTACT US: Governor Hearing From You Michael S. Steele For further information about this project, please contact: Lt. Governor Fall 2004 Open Houses Lorenzo Bryant, Project Manager En Español: Jose M. Vazquéz Robert L. Flanagan Maryland Transit Administration Maryland Transit Administration MDOT Secretary 6 Saint Paul Street, 9th Floor 8720 Georgia Avenue, Suite 904 Plan to Attend Almost 300 people attended seven Red Line Open Houses Silver Spring, MD 20910 held between October 26 and November 9, 2004. At the Baltimore, MD 21202 Upcoming Public Open Open Houses, participants received updates on the status Lisa L. Dickerson (301) 565-9665 of the project, provided input, and received information on MTA Acting Administrator Telephone: 410-767-3754 Houses on the Red Line alternatives under study. The Open Houses were advertised in a project mailer and the website, as well as local newspapers. 410-539-3497 TTY The Maryland Transit Administration (buildings, historic districts, archaeological Fliers were also distributed to locations along the Red Line (MTA), in cooperation with Baltimore City, or cultural sites) that are eligible for the corridor. Materials presented at the Open Houses can Email: [email protected] | [email protected] Baltimore County, and federal and state National Register of Historic Places. If be viewed by logging on to the project website, resource agencies, will be preparing a you are interested in participating in the www.baltimoreregiontransitplan.com. Website: www.baltimoreregiontransitplan.com Draft Environmental Impact Statement Section 106-Public Involvement process, (DEIS) for the Red Line Study. preservation specialists will be available at Major themes from the Open House comments received Alternate formats of Red Line information can be provided upon request. -

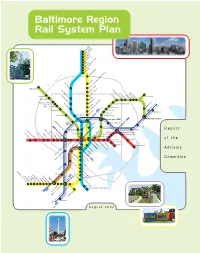

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Accessible Transportation Options for People with Disabilities and Senior Citizens

Accessible Transportation Options for People with Disabilities and Senior Citizens In the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area JANUARY 2017 Transfer Station Station Features Red Line • Glenmont / Shady Grove Bus to Airport System Orange Line • New Carrollton / Vienna Parking Station Legend Blue Line • Franconia-Springfield / Largo Town Center in Service Map Hospital Under Construction Green Line • Branch Ave / Greenbelt Airport Full-Time Service wmata.com Yellow Line • Huntington / Fort Totten Customer Information Service: 202-637-7000 Connecting Rail Systems Rush-Only Service: Monday-Friday Silver Line • Wiehle-Reston East / Largo Town Center TTY Phone: 202-962-2033 6:30am - 9:00am 3:30pm - 6:00pm Metro Transit Police: 202-962-2121 Glenmont Wheaton Montgomery Co Prince George’s Co Shady Grove Forest Glen Rockville Silver Spring Twinbrook B30 to Greenbelt BWI White Flint Montgomery Co District of Columbia College Park-U of Md Grosvenor - Strathmore Georgia Ave-Petworth Takoma Prince George’s Plaza Medical Center West Hyattsville Bethesda Fort Totten Friendship Heights Tenleytown-AU Prince George’s Co Van Ness-UDC District of Columbia Cleveland Park Columbia Heights Woodley Park Zoo/Adams Morgan U St Brookland-CUA African-Amer Civil Dupont Circle War Mem’l/Cardozo Farragut North Shaw-Howard U Rhode Island Ave Brentwood Wiehle-Reston East Spring Hill McPherson Mt Vernon Sq NoMa-Gallaudet U New Carrollton Sq 7th St-Convention Center Greensboro Fairfax Co Landover Arlington Co Tysons Corner Gallery Place Union Station Chinatown Cheverly 5A to -

MOUNT WINANS Contents Exhibits Overview

SOUTH BALTIMORE GATEWAY COMPLETE STREETS PLAN MOUNT WINANS Contents Exhibits Overview .............................................................................. 2 1: Neighborhood Map ..................................................... 2 Land Use .............................................................................. 4 2: Land Use Map ............................................................... 4 Existing Transportation ................................................... 5 3: Sidewalk Map ................................................................ 6 Street Typology ................................................................. 8 4: Baltimore City Bike Master Plan Map .................... 7 Development Traffic Impacts and Mitigation ....... 15 5: Street Typology Map .................................................. 9 City and Other Agency Projects ................................ 15 6: Complete Streets Typologies and Elements ..... 10 Neighborhood Complete Streets Inventory .......... 16 7: Community Collector Street Typology ............... 12 Community Connections ............................................. 16 8: Neighborhood Street Type Typology ................. 13 Complete Streets Plan Principles ............................... 18 9: Service / Alleyways Street Typology .................... 14 Complete Streets Plan ................................................... 19 10: Community Connections Map ............................. 17 Appendix I: Complete Street Inventory……………….22 11: Complete Streets Plan Map -

Appendix E Detailed Case Studies

Guidelines for Providing Access to Public Transportation Stations APPENDIX E DETAILED CASE STUDIES Revised Final Report 2011 Page E-1 Detailed Case Studies Guidelines for Providing Access to Public Transportation Stations TABLE OF CONTENTS Case Study Summary ............................................................................................................................... E-3 Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) .............................................................................................................. E-7 Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) ........................................... E-21 Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) ................................................................ E-33 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) ..................................................................... E-41 Metro-North Railroad ............................................................................................................................. E-57 New Jersey Transit (NJT) ....................................................................................................................... E-67 OC Transpo .............................................................................................................................................. E-81 Regional Transit District Denver (RTD) ............................................................................................... E-93 Sound Transit ........................................................................................................................................ -

CHERRY HILL Contents Exhibits Overview

SOUTH BALTIMORE GATEWAY COMPLETE STREETS PLAN CHERRY HILL Contents Exhibits Overview .............................................................................. 2 1: Neighborhood Map ..................................................... 2 Land Use .............................................................................. 4 2: Land Use Map ............................................................... 4 Existing Transportation ................................................... 5 3: Sidewalk Map ................................................................ 6 Street Typology ................................................................. 8 4: Baltimore City Bike Master Plan Map .................... 7 Development Traffic Impacts and Mitigation ....... 16 5: Street Typology Map .................................................. 9 City and Other Agency Projects ................................ 16 6: Complete Streets Typologies and Elements ..... 10 Neighborhood Complete Streets Inventory .......... 19 7: Urban Arterial Street Typology .............................. 12 Community Connections ............................................. 20 8: Community Collector Street Typology ............... 13 Complete Streets Plan Principles ............................... 21 9: Neighborhood Street Type Typology ................. 14 Complete Streets Plan ................................................... 22 10: Service / Alleyways Street Typology .................. 15 Appendix I: Complete Streets Inventory…………….26 11: Community Connections Map -

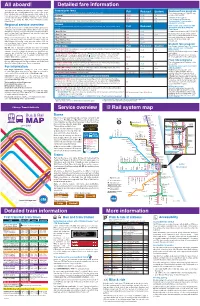

First Bus All Aboard! Rail System Map Detailed Fare in for Ma Tion Service

All aboard! Detailed fare in for ma tion First bus / last bus times This map gives detailed information about Chica go Transit Base/regular fares All CTA and Pace buses are accessible to people with disabilities. # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUN./HOL. # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUN./HOL. # ROUTE & TERMINALS WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUN./HOL. Authority bus and el e vat ed/sub way train ser vice, and shows Full Reduced Student Reduced fare program X Pay-per-ride fares, as deducted from value in a Ventra Transit Account Use this chart to determine days, hours of service, where each Pace subur ban bus and Metra commut er train routes in the The following groups are eligible to pay a reduced fare on CTA: CTA ser vice area. It is up dat ed regularly, and avail able at ‘L’ train fare $2.50* $1.25 75¢ route begins and ends, and first and last buses in each direction Wallace/Racine West Lawrence Inner Drive/Michigan Express 44 Racine/87th north to Halsted (Orange) 4:30a-9:40p 8:00a-6:00p 9:00a-6:00p 81W Cumberland (Blue) east to Jeff Park (Blue) 5:25a-10:25p 5:20a-10:20p 8:45a-10:15p 14 6 Berwyn (Red) south to Museum Campus 5:55a-10:40p 6:00a-10:40p 6:00a-10:40p † on each route. X X X CTA rail stations, Metra down town terminals, visitor cen ters, Bus fare $2.25 $1.10 75¢ Children 7 through 11 Halsted (Orange) south to Racine/87th 5:15a-10:25p 8:50a-6:45p 9:45a-6:45p Museum Campus north to Berwyn (Red) 7:00a-11:35p 6:50a-11:40p 6:50a-11:35p X Jeff Park X (Blue) west to Cumberland X (Blue) 4:55a-9:55p 4:50a-9:50p 8:20a-9:50p air ports, or by calling the RTA. -

The Transportation Dividend Transit Investments And

REPORT FEBRUARY 2018 THE TRANSPORTATION DIVIDEND TRANSIT INVESTMENTS AND THE MASSACHUSETTS ECONOMY II A BETTER CITY THE TRANSPORTATION DIVIDEND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A Better City managed the preparation of this report thanks to the generous funding of the Barr Foundation and the Boston Foundation. We are also grateful to James Aloisi for his invaluable editorial counsel. REPORT TEAM A Better City • Richard Dimino • Thomas Nally • Kathryn Carlson AECOM • Alden Raine • Toni Horst A Better City is a diverse group of business leaders united AECOM is a global network of design, around a common goal—to enhance Boston and the region’s engineering, construction and management economic health, competitiveness, vibrancy, sustainability and professionals partnering with clients to quality of life. By amplifying the voice of the business community imagine and deliver a better world. Today through collaboration and consensus across a broad range of listed at #161 on the Fortune 500 as one stakeholders, A Better City develops solutions and influences of America’s largest companies, AECOM’s policy in three critical areas central to the Boston region’s economic talented employees serve clients in more competitiveness and growth: transportation and infrastructure, than 150 countries around the world. AECOM land use and development, and energy and environment. is a leader in the US transportation industry. To view a hyperlinked version of this report online, go to http://www.abettercity.org/docs-new/ TransportationDividend.pdf. Concept: Minelli, Inc. Design: -

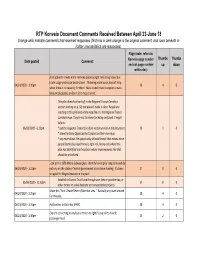

RTP Konveio Document Comments Received Between April 23-June 18

RTP Konveio Document Comments Received Between April 23-June 18 Orange cells indicate comments that received responses (first row in dark orange is the original comment, and rows beneath in lighter orange/italics are responses) Page (note: refers to Thumbs Thumbs Date posted Comment Konveio page number and not page number up down within doc) Add option to create more rail lines (subway/light rail) along heavy bus route usage and major destinations. Throwing more buses doesn't help 04/24/2020 - 1:20pm 26 4 0 when there is no capacity for them. Mass transit must transport a mass amount of people, or else it isn't mass transit. This plan does that (sort of) in the Regional Transit Corridors section starting on p. 58, but doesn't make it clear. People are reacting to this pink and white map like it is the Regional Transit Corridors map. They're not to blame for being confused. It might help to: 06/03/2020 - 6:12pm * put the Regional Transit Corridors section earlier in the document 26 1 0 * show the Early Opportunity Corridors on their own map * say more about the opportunity to build transit that moves more people faster (bus rapid transit, light rail, heavy rail) where this plan has identified are the places where improvements like that should be prioritized Look at the 1978 Metro Subway plan. Identify funding for long term and do 04/24/2020 - 1:22pm not rely on the state or federal government to continue funding. It's been 27 8 0 stripped for illogical reasons in the past! Establish a Transit Trust Fund through user fees or gasoline tax, or 05/06/2020 - 11:50pm 27 8 0 other means to solely dedicate to transportation projects. -

Chicago Downtown Chicago Connections

Stone Scott Regional Transportation 1 2 3 4 5Sheridan 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dr 270 ter ss C en 619 421 Edens Plaza 213 Division Division ne 272 Lake Authority i ood s 422 Sk 422 u D 423 LaSalle B w 423 Clark/Division e Forest y okie Rd Central 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie 422 The Regional Transportation Authority r P GLENVIEW 800W 600W 200W nonstop between Michigan/Delaware 620 421 0 E/W eehan Preserve Wilmette C Union Pacific/North Line 3rd 143 l Forest Baha’i Temple F e La Elm ollw Green Bay a D vice 4th v Green Glenview Glenview to Waukegan, Kenosha and Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T i lo 210 626 Evanston Elm n (RTA) provides financial oversight, Preserve bard Linden nonstop between Michigan/Delaware e Dewes b 421 146 s Wilmette 221 Dear Milw Foster and Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) funding, and regional transit planning R Glenview Rd 94 Hi 422 221 i i-State 270 Cedar nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Rand v r Emerson Chicago Downtown Central auk T 70 e Oakton National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena Map Legend Hill 147 r Cook Co 213 and Marine/Foster (5200N) for the three public transit operations Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central Courts k Central 213 93 Maple College 201 Sheridan nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Holy 422 S 148 Old Orchard Gross 206 C Northwestern Univ Hobbie and Marine/Irving Park (4000N) Dee Family yman 270 Point Central St/ CTA Trains Hooker Wendell 22 70 36 Bellevue L in Northeastern Illinois: The Chicago olf Cr Chicago A Harrison 54A 201 Evanston 206 A 8 A W Sheridan Medical 272 egan osby Maple th Central Ser 423 201 k Illinois Center 412 GOLF Westfield Noyes Blue Line Haines Transit Authority (CTA), Metra and Antioch Golf Glen Holocaust 37 208 au 234 D Golf Old Orchard Benson Between O’Hare Airport, Downtown Newberry Oak W Museum Nor to Golf Golf Golf Simpson EVANSTON Oak Research Sherman & Forest Park Oak Pace Suburban bus. -

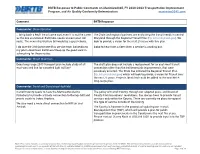

Public Comments Received and BRTB Response

BRTB Response to Public Comments on Maximize2045, FY 2020-2023 Transportation Improvement Program, and Air Quality Conformity Determination maximize2045.com Comment BRTB Response Commenter: Steve Sprecher … bring back a Red Line of some sort, even if is not the same The State and regional partners are evaluating the transit needs in central as the one envisioned. Baltimore needs an east-west rail Maryland through the Regional Transit Plan (rtp.mta.maryland.gov). We route. The new infrastructure bill would be a great choice. look to provide a vision for the next 25 years with this plan. I do love the 310 Commuter Bus service from Columbia to Good to hear from a rider when a service is working out. my job in downtown Baltimore! Keep up the good work in advocating for these routes. Commenter: Stuart Stainman Does long range 2045 transport plan include study of alt The draft plan does not include a replacement for an east-west transit east-west red line for canceled light rail line? connection other than the BaltimoreLink improvements that were previously enacted. The State has initiated the Regional Transit Plan (rtp.mta.maryland.gov) which will look to provide a vision for Transit over the next 25 years. Projects identified could be added to the next BRTB long-range plan. Commenter: David and Constance Highfield Carroll County needs to have the Metro extended to The policy of Carroll County, through our adopted plans and Board of Finksburg to provide a timely connection to Owings Mill and County Commissioners’ resolutions, has always been to provide transit points south to Johns Hopkins. -

Transportation Network Directory for People with Disabilities and Adults 50+ Montgomery County, Md

TRANSPORTATION NETWORK DIRECTORY FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES AND ADULTS 50+ MONTGOMERY COUNTY, MD REGIONAL CONNECTIONS CROSS COUNTY AND BEYOND Montgomery County, Maryland (‘the County’) cannot guarantee the relevance, completeness, accuracy, or timeliness of the information provided on the non-County links. The County does not endorse any non-County organizations' products, services, or viewpoints. The County is not responsible for any materials stored on other non-County web sites, nor is it liable for any inaccurate, defamatory, offensive or illegal materials found on other Web sites, and that the risk of injury or damage from viewing, hearing, downloading or storing such materials rests entirely with the user. Alternative formats of this document are available upon request. This is a project of the Montgomery County Commission on People with Disabilities. To submit an update, add or remove a listing, or request an alternative format, please contact: [email protected], 240-777-1246 (V), MD Relay 711. Frederick and Howard County Maryland Transit Administration (MTA) Commuter Bus Route 203: Columbia to Bethesda Route 204: Frederick to College Park Route 305: Columbia / Silver Spring / Washington, D.C. Route 315: Columbia / Silver Spring / Washington, D.C. Route 325: Columbia / Silver Spring / Washington, D.C. Route 505: Hagerstown / Myersville to Shady Grove / Rock Spring Business Park Route 515: Frederick / Urbana / Shady Grove / Rock Spring Business Park Commuter Bus Fare: One way full fare is $5.00. Major debit/credit cards are accepted on bus for one-way fares for the current trip. No debit/credit card one-way fares can be purchased for future trips.