Appendix E Detailed Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naylor Road Metro Station Area Accessibility Study

Naylor Road Metro Station Area Accessibility Study Pedestrian and Bicycle Metro Station Access Transportation Land-Use Connection (TLC) National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission May 2011 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Recommendations ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Study Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Study Process ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Background .................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Planning Context and Past Studies ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Existing Conditions and Challenges ............................................................................................................. 10 Public Outreach ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Appendix 5 Station Descriptions And

Appendix 5 Station Descriptions and Technical Overview Stage 2 light rail transit (LRT) stations will follow the same standards, design principles, and connectivity and mobility requirements as Stage 1 Confederation Line. Proponent Teams were instructed, through the guidelines outlined in the Project Agreement (PA), to design stations that will integrate with Stage 1, which include customer facilities, accessibility features, and the ability to support the City’s Transportation Master Plan (TMP) goals for public transit and ridership growth. The station features planned for the Stage 2 LRT Project will be designed and built on these performance standards which include: Barrier-free path of travel to entrances of stations; Accessible fare gates at each entrance, providing easy access for customers using mobility devices or service animals; Tactile wayfinding tiles will trace the accessible route through the fare gates, to elevators, platforms and exits; Transecure waiting areas on the train platform will include accessible benches and tactile/Braille signs indicating the direction of service; Tactile warning strips and inter-car barriers to keep everyone safely away from the platform edge; Audio announcements and visual displays for waiting passengers will precede each train’s arrival on the platform and will describe the direction of travel; Service alerts will be shown visually on the passenger information display monitors and announced audibly on the public-address system; All wayfinding and safety signage will be provided following the applicable accessibility standards (including type size, tactile signage, and appropriate colour contrast); Clear, open sight lines and pedestrian design that make wayfinding simple and intuitive; and, Cycling facilities at all stations including shelter for 80 per cent of the provided spaces, with additional space protected to ensure cycling facilities can be doubled and integrated into the station’s footprint. -

BRTOD – State of the Practice in the United States

BRTOD – State of the Practice in the United States By: Andrew Degerstrom September 2018 Contents Introduction .............................................................................................1 Purpose of this Report .............................................................................1 Economic Development and Transit-Oriented Development ...................2 Definition of Bus Rapid Transit .................................................................2 Literature Review ..................................................................................3 BRT Economic Development Outcomes ...................................................3 Factors that Affect the Success of BRTOD Implementation .....................5 Case Studies ...........................................................................................7 Cleveland HealthLine ................................................................................7 Pittsburgh Martin Luther King, Jr. East Busway East Liberty Station ..... 11 Pittsburgh Uptown-Oakland BRT and the EcoInnovation District .......... 16 BRTOD at home, the rapid bus A Line and the METRO Gold Line .........20 Conclusion .............................................................................................23 References .............................................................................................24 Artist rendering of Pittsburgh's East Liberty neighborhood and the Martin Luther King, Jr. East Busway Introduction Purpose of this Report If Light Rail Transit (LRT) -

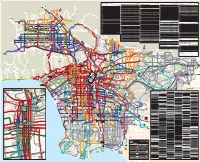

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

Comments to Paine Field Airport; They Have Been Noted

SnohoniLt 1) • 17’ 1 J ,4$~ic~ Comments Countvkitport u amer len ~F Environtuental Assessinen~ ~~S4LW, LOft. 9~t7f NSCtEwJ cn~, cc~c i2~k ~u u~ COMMENTS: A~ 4o~i-c ~M ~—Tw*~ C Ia Dave Waggoner Cayla Morgan Director Environmental Protection Spedalist Snohomish County Airport Seattle Airports District Office Comments to 3220 100th Street Southwest or Federal Aviation Administration Everett, Washington 98204 1601 Lind Avenue, SW Barnard Dunkelberg >? Company Email. [email protected] Renton, Washington 98057-3356 BridgeNet International Email. [email protected] Synergy Consultants Gibson Traffic Consultants Thank You! D.1 Response to Comment Dear Jeanne and George Dalton: Thank you for your comments to Paine Field Airport; they have been noted. D.2 -Original Message— From: [email protected] [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Wednesday, January 20, 2010 5:40 PM To: Waggoner, Dave; Dolan, Bill; Ryk Dunkelberg; Ryan Hayes Cc: [email protected]; [email protected]; Roland. J.McKee@faa . gov Subject: Fw: Paine Field review Cayla Morgan Environmental Protection Specialist Seattle Airports District Office Federal Aviation Administration 425—227—2653 Forwarded by Cayla Morgan/ANM/FAA on 01/20/2010 04:38 PM I > From: I I > I > IStephen Dana <[email protected]> > > I To: I > I > Cayla Morgan/ANM/FAA@FAA I > > Date: I > > 101/20/2010 03:22 PM > > Subject: I > > IPaine Field review > D.3 January 19, 2010 Cayla Morgan Environmental Protection Specialist Seattle Airport District Office, FAA 1601 Lind Ave SW Renton, WA 98057 Ms. Morgan, The matter of commercial air service at Paine field is up for environmental review before your office in the coming weeks. -

Pentagon City Metro Station Second Elevator Transportation Commission

Pentagon City Metro Station Second Elevator Transportation Commission July 01, 2021 Pentagon City Metro Station Second Elevator • BACKGROUND: The Pentagon City Metrorail station is one of the highest in terms of ridership among stations in Northern Virginia,. • Provides access to multiple retail, government, and commercial office buildings, and is a transfer point for regional and local transit buses and numerous private bus services. • Construction of a new second elevator Intersection of S Hayes and S 12th Streets on the north side of the passageway corresponds to the new second New Elevator Existing elevator being in the general area of Elevator the pedestrian path for people crossing S. Hayes Street. July 01, 2021 Pentagon City Metro Station Second Elevator Project Scope: • The second elevator will eliminate the need to cross six (6) lanes of traffic, two parking lanes, and a bike lane to reach the elevator on the east side of S. Hayes Street. • Improves ADA access and access for passengers with strollers and luggage. • Provide redundancy, in accordance with current WMATA design criteria, when one of the elevators is out of service for any reason. July 01, 2021 Pentagon City Metro Station Second Elevator Construction Phase: On January 25, 2021, Arlington County received two (2) bids • The low bidder, W.M. Schlosser Company, Inc. was awarded the contract on April 19, 2021 for $6.4 mil. • The County and Procon (CM), will work together with the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) to ensure construction is performed -

Public Hearing Will Pertaintoapplicablefares Asmodified

Proposed Changes in Fares, Crossing Charges, and Service Hearings will be held on proposed changes in fares at the locations, dates, and times noted below. The public is invited to comment on the proposed changes which are summarized below and pertain, as applicable, to MTA Long Island Rail Road (LIRR), MTA Metro-North Railroad (Metro-North), MTA New York City Transit (NYCT), the Manhattan and Bronx Surface Transit Operating Authority (MaBSTOA), and MTA Bus and to crossing charges on MTA Bridges &Tunnels (Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority). The fare and toll proposals allow for a range of options to be considered; increases to fares or crossing charges may be less than the maximum amounts specified. Following the hearings, after considering public comment, the Boards of the MTA and its affiliated agencies will decide which potential fare adjustments to adopt. Space limitations prevent newspaper publication of each proposed new fare or crossing charge. For more complete descriptions of these potential changes, please consult information posted at MTA stations and on the MTA website, www.mta.info, or call (646) 252-6777. Following hearings, one or more of the proposed changes listed below could be adopted: NYCT, MaBSTOA, MTA Bus, SIR: LIRR & Metro North: Fares for Subway (NYCT), Local Bus (NYCT, MaBSTOA, and MTA Bus), and SIR: • Increase monthly tickets up to 4% and not more than $15. Increase weekly Base Single Ride Fare (currently $3.00 for Single Ride Ticket, and $2.75 for tickets up to 4% and not more than $5.75. Increase fares in an amount from 0 cash payment and Pay-Per-Ride (zero) to 10% on all other ticket types, with any increase greater than 6% held MetroCard®): to a maximum increase of $0.50 per trip. -

This Re-Route Will Start at the Biginning of Revenue Service Untill B.C.C

THIS RE-ROUTE WILL START AT THE BIGINNING OF REVENUE SERVICE UNTILL B.C.C. GIVES THE ALL CLEAR. REROUTE ADVISORY: Route #2 Ponce De Leon, #3 Auburn Ave, #6 Emory, #9 Boulevard/Tilson Road, #21 Memorial Drive, #26 Marietta Street, #36 Virginia Highland, #40 Downtown, #42 Pryor Road, #49 McDonough Blvd, #50 D.L. Hollowell Pkwy, #51 J.E. Boone, #55 Jonesboro Road, #94 Northside Drive, #102 Little Five Points, #107 Glenwood, #186 Rainbow Drive, #809 Monroe Drive, #813 Atlanta Student Movement, #816 North Highland Ave, #832 Grant Park, and #899 Old Fourth Ward. WHAT: 2020 Publix Atlanta Marathon & 5k WHERE: The Marathon will start at Marietta Street and Centennial Olympic Park Drive. The Route/Course will travel through various streets in the City of Atlanta and Dekalb County. WHEN: Sunday, March 1, 2020 TIMES: 7:00 a.m. – 2:00 p.m. or Until the All clear is given by B.C.C. Buses in and around the Marathon will be rerouted during the Marathon/5k. Bus routes intersecting with Race/Runners will be delayed. Atlanta Police will allow traffic to flow between gaps in the Race. Reroute as follows: OUTBOUND: Route #2 from North Avenue Station to East Lake Station (South Loop) Regular route Expect Delays crossing North Highland Avenue. INBOUND: Route #2 from East Lake Station to North Avenue Station Regular route Expect Delays crossing North Highland Avenue. Regular route Page 1 of 20 OUTBOUND: Route #3 from H.E. Holmes Station to West End Station Continue M.L.K. Jr. Drive Right – Joseph E. Lowery Blvd. -

![[Title Over Two Lines (Shift+Enter to Break Line)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4038/title-over-two-lines-shift-enter-to-break-line-134038.webp)

[Title Over Two Lines (Shift+Enter to Break Line)]

BUS TRANSFORMATION PROJECT White Paper #2: Strategic Considerations October 2018 DRAFT: For discussion purposes 1 1 I• Purpose of White Paper II• Vision & goals for bus as voiced by stakeholders III• Key definitions IV• Strategic considerations Table of V• Deep-dive chapters to support each strategic consideration Contents 1. What is the role of Buses in the region? 2. Level of regional commitment to speeding up Buses? 3. Regional governance / delivery model for bus? 4. What business should Metrobus be in? 5. What services should Metrobus operate? 6. How should Metrobus operate? VI• Appendix: Elasticity of demand for bus 2 DRAFT: For discussion purposes I. Purpose of White Paper 3 DRAFT: For discussion purposes Purpose of White Paper 1. Present a set of strategic 2. Provide supporting analyses 3. Enable the Executive considerations for regional relevant to each consideration Steering Committee (ESC) to bus transformation in a neutral manner set a strategic direction for bus in the region 4 DRAFT: For discussion purposes This paper is a thought piece; it is intended to serve as a starting point for discussion and a means to frame the ensuing debate 1. Present a The strategic considerations in this paper are not an set of strategic exhaustive list of all decisions to be made during this considerations process; they are a set of high-level choices for the Bus Transformation Project to consider at this phase of for regional strategy development bus transformation Decisions on each of these considerations will require trade-offs to be continually assessed throughout this effort 5 DRAFT: For discussion purposes Each strategic consideration in the paper is 2. -

Proposed Program of High Capacity Transit Improvements City of Atlanta DRAFT

Proposed Program of High Capacity Transit Improvements City of Atlanta DRAFT Estimated Capital Cost (Base Year in Estimated O&M Cost (Base Year in Millions) Millions) Project Description Total Miles Local Federal O&M Cost Over 20 Total Capital Cost Annual O&M Cost Share Share Years Two (2) miles of heavy rail transit (HRT) from HE Holmes station to a I‐20 West Heavy Rail Transit 2 $250.0 $250.0 $500.0 $13.0 $312.0 new station at MLK Jr Dr and I‐285 Seven (7) miles of BRT from the Atlanta Metropolitan State College Northside Drive Bus Rapid Transit (south of I‐20) to a new regional bus system transfer point at I‐75 7 $40.0 N/A $40.0 $7.0 $168.0 north Clifton Light Rail Four (4) miles of grade separated light rail transit (LRT) service from 4 $600.0 $600.0 $1,200.0 $10.0 $240.0 Contingent Multi‐ Transit* Lindbergh station to a new station at Emory Rollins Jurisdicitional Projects I‐20 East Bus Rapid Three (3) miles of bus rapid transit (BRT) service from Five Points to 3 $28.0 $12.0 $40.0 $3.0 $72.0 Transit* Moreland Ave with two (2) new stops and one new station Atlanta BeltLine Twenty‐two (22) miles of bi‐directional at‐grade light rail transit (LRT) 22 $830 $830 $1,660 $44.0 $1,056.0 Central Loop service along the Atlanta BeltLine corridor Over three (3) miles of bi‐directional in‐street running light rail transit Irwin – AUC Line (LRT) service along Fair St/MLK Jr Dr/Luckie St/Auburn 3.4 $153 $153 $306.00 $7.0 $168.0 Ave/Edgewood Ave/Irwin St Over two (2) miles of in‐street bi‐directional running light rail transit Downtown – Capitol -

SOUND TRANSIT MOTION NO. M99-75 Mukilteo Memorandum Of

SOUND TRANSIT MOTION NO. M99-75 Mukilteo Memorandum of Understanding Relating to the Federal Surplus Action of the Mukilteo Tank Farm Parcel BACKGROUND AND COMMENTS Meeting: Date: Type of Action: Staff Contact: Phone: Board of Directors 10/28/99 Discussion/Possible Action Paul Price 398-5111 Barry Hennelly 689-4925 ACTION: Motion No. M99-75 would authorize the Executive Director to execute a Memorandum of Understanding establishing cooperation between Sound Transit, Port of Everett, City of Mukilteo, Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), and City of Everett for the acquisition of the Mukilteo Tank Farm property from the United States Air Force through the Department of Defense surplus property process. BACKGROUND: Sound Move calls for Sounder commuter rail to serve the City of Mukilteo as part of the Everett-to Seattle project. This Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) allows Sound Transit to participate in a process whereby the federal government will surplus property (the Mukilteo Tank Farm) to the Port of Everett, WSDOT Ferries, Sound Transit and cities of Mukilteo and Everett. The Port of Everett is the lead applicant. The Mukilteo tank farm is a former fuel tank farm site, covering approximately 22 acres of the City of Mukilteo's waterfront. This property is adjacent to Sounder's preferred Mukilteo station location. The property would be used to provide land for beneficial public uses on Mukilteo's waterfront. Sound Transit would be allocated a portion of land sufficient to support Sounder Commuter Rail needs at the Mukilteo Station. Opportunities identified for consideration by the parties of this MOU may include: 1. -

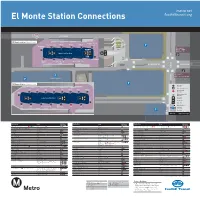

El Monte Station Connections Foothilltransit.Org

metro.net El Monte Station Connections foothilltransit.org BUSWAY 10 Greyhound Foothill Transit El Monte Station Upper Level FT Silver Streak Discharge Only FT486 FT488 FT492 Eastbound Metro ExpressLanes Walk-in Center Discharge 24 25 26 27 28 Only Bus stop for: 23 EMT Red, EMT Green EMS Civic Ctr Main Entrance Upper Level Bus Bays for All Service B 29 22 21 20 19 18 Greyhound FT481 FT Silver Streak Metro Silver Line Metro Bike Hub FT494 Westbound RAMONA BL RAMONA BL A Bus stop for: EMS Flair Park (am/pm) Metro Parking Structure Division 9 Building SANTA ANITA AV El Monte Station Lower Level 1 Bus Bay A Bus Stop (on street) 267 268 487 190 194 FT178 FT269 FT282 2 Metro Rapid 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Bus Bay 577X Metro Silver Line 8 18 Bus Bay Lower Level Bus Bays Elevator 76 Escalator 17 Bike Rail 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 EMS Bike Parking 270 176 Discharge Only Commuter 770 70 Connection Parking Building 13-0879 ©2012 LACMTA DEC 2012 Subject to Change Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Street Stop Street Stop Street Stop 7th St/Metro Center Rail Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 Hacienda Heights FT282 16 Pershing Square Metro Rail Station Metro Silver Line , 70, 76, 770, 1 2 17 18 37th St/USC Transitway Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 FT Silver Streak 19 20 21 Harbor Fwy Metro Rail Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 Pomona TransCenter ÅÍ FT Silver Streak 28 Alhambra 76, 176 6 17 Highland Park 176 6 Altadena 267, 268 9 10 Puente Hills Mall FT178, FT282 14 16 Industry Å 194, FT282 13 16 Arcadia 268,