Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation in the Yangtze Water Resources Management in China: a Legal and Institutional Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irrigation of World Agricultural Lands: Evolution Through the Millennia

water Review Irrigation of World Agricultural Lands: Evolution through the Millennia Andreas N. Angelakιs 1 , Daniele Zaccaria 2,*, Jens Krasilnikoff 3, Miquel Salgot 4, Mohamed Bazza 5, Paolo Roccaro 6, Blanca Jimenez 7, Arun Kumar 8 , Wang Yinghua 9, Alper Baba 10, Jessica Anne Harrison 11, Andrea Garduno-Jimenez 12 and Elias Fereres 13 1 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion and Union of Hellenic Water Supply and Sewerage Operators, 41222 Larissa, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Land, Air, and Water Resources, University of California, California, CA 95064, USA 3 School of Culture and Society, Department of History and Classical Studies, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark; [email protected] 4 Soil Science Unit, Facultat de Farmàcia, Universitat de Barcelona, 08007 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 5 Formerly at Land and Water Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations-FAO, 00153 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Catania, 2 I-95131 Catania, Italy; [email protected] 7 The Comisión Nacional del Agua in Mexico City, Del. Coyoacán, México 04340, Mexico; [email protected] 8 Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi 110016, India; [email protected] 9 Department of Water Conservancy History, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing 100048, China; [email protected] 10 Izmir Institute of Technology, Engineering Faculty, Department of Civil -

Emergence, Concept, and Understanding of Pan-River-Basin

HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com International Soil and Water Conservation Research 3 (2015) 253–260 www.elsevier.com/locate/iswcr Emergence, concept, and understanding of Pan-River-Basin (PRB) Ning Liu The Ministry of Water Resources, Beijing 10083, China Received 10 December 2014; received in revised form 20 September 2015; accepted 11 October 2015 Available online 4 November 2015 Abstract In this study, the concept of Pan-River-Basin (PRB) for water resource management is proposed with a discussion on the emergence, concept, and application of PRB. The formation and application of PRB is also discussed, including perspectives on the river contribution rates, harmonious levels of watershed systems, and water resource availability in PRB system. Understanding PRB is helpful for reconsidering river development and categorizing river studies by the influences from human projects. The sustainable development of water resources and the harmonization between humans and rivers also requires PRB. & 2015 International Research and Training Center on Erosion and Sedimentation and China Water and Power Press. Production and Hosting by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Keywords: Aquatic Base System; Harmonization of humans and rivers; Pan-River-Basin; River contribution rate; Water transfer 1. Emergence of Pan-River-Basin A river basin (or watershed) is the area of land where surface water, including rain, melting snow, or ice, converges to a single point at a lower elevation, usually the exit of the basin. From the exit, the water joins another water body, such as a river, lake, reservoir, estuary, wetland, or the ocean. -

Assessment of Japanese and Chinese Flood Control Policies

京都大学防災研究所年報 第 53 号 B 平成 22 年 6 月 Annuals of Disas. Prev. Res. Inst., Kyoto Univ., No. 53 B, 2010 Assessment of Japanese and Chinese Flood Control Policies Pingping LUO*, Yousuke YAMASHIKI, Kaoru TAKARA, Daniel NOVER**, and Bin HE * Graduate School of Engineering ,Kyoto University, Japan ** University of California, Davis, USA Synopsis The flood is one of the world’s most dangerous natural disasters that cause immense damage and accounts for a large number of deaths and damage world-wide. Good flood control policies play an extremely important role in preventing frequent floods. It is well known that China has more than 5000 years history and flood control policies and measure have been conducted since the time of Yu the great and his father’s reign. Japan’s culture is similar to China’s but took different approaches to flood control. Under the high speed development of civil engineering technology after 1660, flood control was achieved primarily through the construction of dams, dykes and other structures. However, these structures never fully stopped floods from occurring. In this research, we present an overview of flood control policies, assess the benefit of the different policies, and contribute to a better understanding of flood control. Keywords: Flood control, Dujiangyan, History, Irrigation, Land use 1. Introduction Warring States Period of China by the Kingdom of Qin. It is located in the Min River in Sichuan Floods are frequent and devastating events Province, China, near the capital Chengdu. It is still worldwide. The Asian continent is much affected in use today and still irrigates over 5,300 square by floods, particularly in China, India and kilometers of land in the region. -

A2Z About China

A2Z about China CA HEMANT C. LODHA www.a2z4all.com Agriculture & Irrigation • 1st world wide in farm output • Largest producer of Rice. Also produces Wheat, Potatos, Sorghum, Peanuts, Tea, Millet, Barley, Cotton, Oil seed, Pork, Tobacco and fish. • China accounts for 1/3rd of total fish production of world. • 15% of total area is cultivated • 13% GDP is from agriculture • 76.17% population is engaged in agriculture • Total Irrigated area 53.8 ha • Dujiangyan irrigation infrastructure built in 256 BC by the Kingdom of Qin, located in Min River in Sichun. It is still in use today to irrigate over 5,300 square kilometers of land in the he Dujiangyan along with the Zhengguo Canal in Shaanixi Privince & Lingqu Canal in Guangxi Province are known as “The three greatest hydraulic engineering projects of the Qin Dynasty • Turpan water system called as karez water system located in the Turpan Depression, Xinjiang, China is also as one of the 3 greatest water projects • China is believed to have more than 80000 Dams • The Three Gorges Dam is the world's larges power station in terms of installed capacity of 21000 MW CA HEMANT C. LODHA www.a2z4all.com 2 Budget, Taxation & GDP • GDP US$ 9.872 Trillion • Individual Income tax highest slab 45% • Corporate Income Tax highest slab 25% • Yearly 9.79 trillion yuan • Major 8 type of taxes categorised as Income tax, Resource Tax, Special purpose tax, custom duty, property tax, Behaviour tax, Agriculture tax, Turnover tax . CA HEMANT C. LODHA www.a2z4all.com 3 Capital & Major Cities • Capital – Beijing • Major cities – Shanghai, Tianjin, Hong Kong, Chongqing, Wuhan, Harbin, Shengyang, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Xian, Changchun, Dalian. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

Recoding Capital: Socialist Realism and Maoist Images (1949-1976) by Young Ji Victoria Lee Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Stanley Abe, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Gennifer Weisenfeld Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT Recoding Capital: Socialist Realism and Maoist Images (1949-1976) by Young Ji Victoria Lee Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Stanley Abe, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Gennifer Weisenfeld An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Young Ji Victoria Lee 2014 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the visual production of capital in socialist realist images during the Maoist era (1949-1976). By deconstructing the pseudo-opposition between capitalism and socialism, my research demonstrates that, although the country was subject to the unchallenged rules of capital and its accumulation in both domestic and international spheres, Maoist visual culture was intended to veil China’s state capitalism and construct its socialist persona. This historical analysis illustrates the ways in which the Maoist regime recoded and resolved the versatile contradictions of capital in an imaginary socialist utopia. Under these conditions, a wide spectrum of Maoist images played a key role in shaping the public perception of socialism as a reality in everyday lives. -

Searchable PDF Format

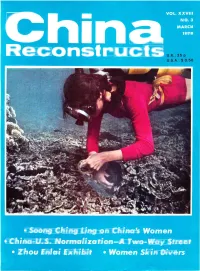

7- a :DL' It- {ol :-_ T[TfolIF AYil Ere iIfrE'II rIjIe irq;t tI.a' l.li iT]Etf;.r a 1t tIo T a I .l a /,a l '^'l o ,i6NIj IET=T 4 ril ol it , f' z 7l tlfrF- 'q CH RECO NSTRUCTS INA PUBLI5HED MONTHLY IN ENGLISH, FRENCH; SPANISH, ARABIC AND BIMONTHLY IN GERMAN BY THE CHINA WELFARE INSTITUIE t\D I ii. (sooNc cHtNG L|NG, CHATRMAN) voL. xxvilt No. s MARCH I979 CONTENIS Our Postbag Modernization and Women Cartoons by Wang Letian a Soong Ching Ling, o Vice-Choir- Across the Land: New Shanghai General mon ol the Notionol People's Con- Petrochemical Works 4 gress, Honorory President ol the No- China's Women in Our New Long March tionol Women's Federotion ond Soong Ching Ling 6 plominent for o holl century in the women's movement, The Women Meet (poem) Rewi Alley 11 tells obout the present roles of Chinese women in Norma ization Has a History A Two-Way the society os well os ot home (p. 6). Street Ma Haide - 12 And on interview with luo Qiong, Record of a Fighting Life Exhibition on Vice-Choirmon of the Notionol Wom- Zhou - 19 Enlai Su Donghai en's Federotion, who soys the tor- Qingdao Port City and Summer Resort get - is not men but complete Zeng Xiang0ing 26 emoncipotion through sociolist pro- Things Chinese: Laoshan Mineral Water e.) gress (p. 33). The Women's Movement in China-An lnter- Pages 6 and 33 view with Luo Qiong 'The Donkey Seller' Bao Wenqing 37 Wood Carving Continues Fu Tianchou 42 The Record of New Spelling ior Names and Places 45 a Fighting Life The Silence Explodes A Play about the Tian An Men Incident- Ren Zhiji and A tour through E^^ t;^^^: I dtl Jldoal 46 on exhibition Stamps ot New China Arts and Crafts 49 on the lote Cultural Notes: 'Women Skin Divers', a Color Premier Zhou Documentary Li Wenbin 50 Enloi. -

Where Is Dujiangyan Irrigation System ? Dujiangyan Irrigation System Is Located in the Min River, Which Is in the Sichuan Province of China

Dujiangyan Irrigation System, China Fish Mouth Levee - Irrigation head at Dujiangyan Irrigation System in China. Dujiangyan is an irrigation system built around 256 BC by the Qin Dynasty in China. The infrastructure was built during the Warring States Period, though construction continued throughout the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties. The various dynasties worked to enlarge and modify the irrigation system. Located in the Min River in China, the irrigation system was very advanced for its time and is still used today, irrigating 5,300 square kilometers (2,046 square miles) of land, supplying water to the Chengdu plains. The Dujiangyan system, along with the Zhengguo Canal (in Shaanxi Province) and Lingqu Canal (in Guangxi Province) are together known as the three great hydraulic engineering projects of the Qin Dynasty. Dujiangyan is considered a feat of engineering, utilizing the natural geography and water features to divert water, drain sediment, and regulate flood and flow control. The system uses no dams, making it a place of interest for scientists as well, as it allows fish to flow freely down the river. The main constructions of the Dujiangyan system include the Yuzui Bypass Dike, the Feishayan Floodgate, and the Baopingkou Diversion Passage. Yuzui, also known as the Fish Mouth Levee, is the irrigation head, resembling a fish mouth. This portion prevents floods by dividing the river into inner and outer streams. The inner stream carries about 60% of the flow normally, but during floods, it carries 40% to protect the surrounding lands. Feishayan, or the Flying Sand Weir is a 200-meter (656 feet) wide opening, connecting the inner and outer streams. -

Ancient Irrigation Canals Mapped from Corona Imageries and Their Implications in Juyan Oasis Along the Silk Road

sustainability Article Ancient Irrigation Canals Mapped from Corona Imageries and Their Implications in Juyan Oasis along the Silk Road Ningke Hu 1,2, Xin Li 2,3,*, Lei Luo 4 and Liwei Zhang 1 1 School of Geography and Tourism, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an 710062, China; [email protected] (N.H.); [email protected] (L.Z.) 2 Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China 3 CAS Center for Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China 4 Institute of Remote Sensing and Digital Earth, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100094, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 May 2017; Accepted: 18 July 2017; Published: 23 July 2017 Abstract: Historical records and archaeological discoveries have shown that prosperous agricultural activities developed in the ancient Juyan Oasis of northwestern China, an important oasis that once flourished on the ancient Silk Road. However, how the irrigation canals were distributed in historical time was unknown. Here, we identified and mapped the spatial distribution of ancient abandoned irrigation canals that were built using CORONA photographs and field inspections. This work found that ancient irrigation canals are large-scale and distributed throughout the desertified environment, with three hierarchical organization of first-, second-, and third-order irrigation canals (the total length of the first- and second-order-irrigation canals is dramatically more than 392 km). This study further indicates that ancient irrigation methods and modern irrigation systems in arid regions of China share the same basic irrigation design. -

Water Management in the Yellow River Basin: Background, Current Critical Issues and Future Research Needs

Research Report 3 Water Management in the Yellow River Basin: Background, Current Critical Issues and Future Research Needs Mark Giordano, Zhongping Zhu, Ximing Cai, Shangqi Hong, Xuecheng Zhang and Yunpeng Xue Postal Address: IWMI, P O Box 2075, Colombo, Sri Lanka Location: 127 Sunil Mawatha, Pelawatte, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka International Telephone: +94-11 2787404, 2784080 Fax: +94-11 2786854 Water Management Email: [email protected] Website: www.iwmi.org/assessment Institute ISSN 1391-9407 ISBN 92-9090-551-4 The Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture takes stock of the costs, benefits and impacts of the past 50 years of water development for agriculture, the water management challenges communities are facing today, and solutions people have developed. The results of the Assessment will enable farming communities, governments and donors to make better-quality investment and management decisions to meet food and environmental security objectives in the near future and over the next 25 years. The Research Report Series captures results of collaborative research conducted under the Assessment. It also includes reports contributed by individual scientists and organizations that significantly advance knowledge on key Assessment questions. Each report undergoes a rigorous peer-review process. The research presented in the series feeds into the Assessment’s primary output—a “State of the World” report and set of options backed by hundreds of leading water and development professionals and water users. Reports in this series may be copied freely and cited with due acknowledgement. Electronic copies of reports can be downloaded from the Assessment website (www.iwmi.org/assessment). If you are interested in submitting a report for inclusion in the series, please see the submission guidelines available on the Assessment website or through written request to: Sepali Goonaratne, P.O. -

Study on Local Water Culture Modeling Mechanism from the Perspective of Cultural Ecology

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 237 3rd International Conference on Humanities Science, Management and Education Technology (HSMET 2018) Study on Local Water Culture Modeling Mechanism from the Perspective of Cultural Ecology: A Case Study of the Middle Yellow River Basin Guan-yu Zhong1,a, Min Xiang1, Ming-dong Jiang1,2,b,*, Hui Zhou3, Shao-xuan Zheng1, Lei Wang1 1 School of Business Administration, Hohai University, Changzhou 213022, China 2Study and Research Group of The thought of socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new er a, Hohai University, Changzhou 213022, China 3College of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Hohai University, Changzhou 213022, China [email protected],[email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: Water culture, Cultural ecology, Cultural management. Abstract. The Middle Yellow River Basin, as an important birthplace of Chinese culture, has an irreplaceable important position in the Chinese cultural landscape. It has created a splendid water culture represented by a self-reliant, hard-working culture and a pioneering and innovative culture. In the course of the formation and development of the water culture in the Middle Yellow River Basin, the material civilization and the ecological environment in the area were persistent to promote each other, and completed the self-enrichment and elevation of the local water culture. Such a molding mechanism continues to circulate in a cyclical manner, embodied in the history of farming civilization and commercial civilization in the Middle Yellow River Basin for more than two thousand years. 1. Introduction Culture is a group of people in a certain geographical area. In a relatively long historical period, due to the continuous recognition, adaptation, utilization, and transformation of the ecological environment in which culture developed, the material civilizations that support its survival and development are produced and accumulated. -

State and Irrigation: Archaeological and Textual Evidence of Water Management in Late Bronze Age China

Article Title: State and irrigation: Archaeological and textual evidence of water management in late Bronze Age China Article Type: Authors: Full name and affiliation; email address if corresponding author; any conflicts of interest First author Yijie Zhuang, Institute of Archaeology, University College London, [email protected]; no any conflicts of interest Abstract Ancient China remains an important case to investigate the relationship between statecraft development and ‘total power’. While important economic and social developments were achieved in the late Neolithic, it was not until the late Bronze Age (first millennium BC) that state-run irrigation systems began to be built. Construction of large-scale irrigation projects, along with walls and defensive facilities, became vital to regional states who were frequently involved in chaotic warfare and desperate to increase food production to feed the growing population. Some of the irrigation infrastructures were brought into light by recent archaeological surveys. We scrutinise fast accumulating archaeological evidence and review rich historical accounts on late Bronze Age irrigation systems. While the credibility of historical documents is often questioned, with a robust integration with archaeological data, they provide important information to understand functions and maintenance of the irrigation projects. We investigate structure and organisation of large-scale irrigation systems built and run by states and their importance to understanding dynamic trajectories to social power in late Bronze Age China. Cleverly designed based on local environmental and hydrological conditions, these projects fundamentally changed water management and farming patterns, with dramatic ecological consequences in different states. Special bureaucratic divisions were created and laws were made to further enhance the functioning of these large-scale irrigation systems. -

Developments in Water Dams and Water Harvesting Systems Throughout History in Different Civilizations

International Journal of Hydrology Book Review Open Access Developments in water dams and water harvesting systems throughout history in different civilizations Abstract Volume 2 Issue 2 - 2018 The use of water for domestic and agricultural purpose is not a new phenomenon. It has been used throughout centuries all over the world. After food, water is the basic Alper Baba,1 Chr Tsatsanifos,2 Fatma El component of human life and their settlement. This paper considers developments in Gohary,3 Jacinta Palerm,4 Saifullah Khan,5 S water dams and water harvesting systems throughout history in different civilisations. Ali Mahmoudian,6 Abdelkader T Ahmed,7 The major component of this review consists of hydraulic dams during Pre-Historical 8,9 Time, Bronze Ages (Minoan Era, Indus Valley Civilization, Early Ancient Egyptian Gökmen Tayfur,1 Yannis G Dialynas, 10 Era, Hittites in Anatolia, and Mycenaean Civilization), Historical Period, (Pre- Andreas N Angelakis 1 Columbian, Archaic Period, Classical Greek and Hellenistic Civilizations, Gandahara Department of Civil Engineering, Izmir Institute of Technology, and Mauryan Empire, Roman Period, and early Chinese dynasties), Medieval times Engineering Faculty, Turkey 2Pangaea Consulting Engineers Ltd, Greece (Byzantine Period, Sui, Tang and Song Dynasties in China, Venetian Period, Aztec 3Department of Water Pollution Research, National Research Civilization, and Incas) and Modern Time (Ottoman Period and Present Time). The Centre, Egypt main aim of the review is to present advances in design and construction of water 4Colegio de Posgraduados de Chapingo, Mexico dams and water harvesting systems of the past civilizations with reference to its use 5Institute of Social Sciences and Directorate of Distance for domestic as well as agricultural purposes, its impact on different civilizations Education, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Pakistan 6 and its comparison to the modern technological era.