The Top-Two, Take Two: Did Changing the Rules Change the Game in Statewide Contests?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Video Games in the Supreme Court

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2017 Newbs Lose, Experts Win: Video Games in the Supreme Court Angela J. Campbell Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1988 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3009812 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Angela J. Campbell* Newbs Lose, Experts Win: Video Games in the Supreme Court Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................... 966 II. The Advantage of a Supreme Court Expert ............ 971 A. California’s Counsel ............................... 972 B. Entertainment Merchant Association’s (EMA) Counsel ........................................... 973 III. Background on the Video Game Cases ................. 975 A. Cases Prior to Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Ass’n .............................................. 975 B. Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Ass’n .......... 978 1. Before the District Court ...................... 980 2. Before the Ninth Circuit ....................... 980 3. Supreme Court ................................ 984 IV. Comparison of Expert and Non-Expert Representation in Brown ............................................. 985 A. Merits Briefs ...................................... 985 1. Statement of Facts ............................ 986 a. California’s Statement -

110Th Congress 17

CALIFORNIA 110th Congress 17 CALIFORNIA (Population 2000, 33,871,648) SENATORS DIANNE FEINSTEIN, Democrat, of San Francisco, CA; born in San Francisco, June 22, 1933; education: B.A., Stanford University, 1955; elected to San Francisco Board of Super- visors, 1970–78; president of Board of Supervisors: 1970–71, 1974–75, 1978; mayor of San Francisco, 1978–88; candidate for governor of California, 1990; recipient: Distinguished Woman Award, San Francisco Examiner; Achievement Award, Business and Professional Women’s Club, 1970; Golden Gate University, California, LL.D. (hon.), 1979; SCOPUS Award for Out- standing Public Service, American Friends of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; University of Santa Clara, D.P.S. (hon.); University of Manila, D.P.A. (hon.), 1981; Antioch University, LL.D. (hon.), 1983; Los Angeles Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith’s Distinguished Serv- ice Award, 1984; French Legion d’Honneur from President Mitterand, 1984; Mills College, LL.D. (hon.), 1985; U.S. Army’s Commander’s Award for Public Service, 1986; Brotherhood/ Sisterhood Award, National Conference of Christians and Jews, 1986; Paulist Fathers Award, 1987; Episcopal Church Award for Service, 1987; U.S. Navy Distinguished Civilian Award, 1987; Silver Spur Award for Outstanding Public Service, San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association, 1987; All Pro Management Team Award for No. 1 Mayor, City and State Magazine, 1987; Community Service Award Honoree for Public Service, 1987; American Jew- ish Congress, 1987; President’s Award, St. Ignatius High School, San Francisco, 1988; Coro Investment in Leadership Award, 1988; President’s Medal, University of California at San Fran- cisco, 1988; University of San Francisco, D.H.L. -

California's Affirmative Action Fight

Research & Occasional Paper Series: CSHE.5.18 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY http://cshe.berkeley.edu/ The University of California@150* CALIFORNIA’S AFFIRMATIVE ACTION FIGHT: Power Politics and the University of California March 2018 John Aubrey Douglass** UC Berkeley Copyright 2018 John Aubrey Douglass, all rights reserved. ABSTRACT This essay discusses the contentious events that led to the decision by the University of California’s Board of Regents to end affirmative action in admissions, hiring and contracting at the university in July 1995. This was a significant decision that provided momentum to California’s passage of Proposition 209 the following year ending “racial preferences” for all of the state’s public agencies. Two themes are offered. In virtually any other state, the debate over university admissions would have bled beyond the confines of a university’s governing board. The board would have deferred to lawmakers and an even more complicated public discourse. The University of California’s unusual status as a “public trust” under the state constitution, however, meant that authority over admissions was the sole responsibility of the board. This provided a unique forum to debate affirmative action for key actors, including Regent Ward Connerly and Governor Pete Wilson, to pursued fellow regents to focus and decide on a hotly debated social issue related to the dispersal of a highly sought public good – access to a selective public university. Two themes are explored. The first focuses on the debate within the university community and the vulnerability of existing affirmative action programs and policies—including a lack of unanimity among the faculty regarding the use of racial preferences. -

December, 2015 Dan Schnur • Director -- Jesse M

December, 2015 Dan Schnur • Director -- Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics, University of Southern California (2008 – present) • Director -- USC Dornsife/LA Times Poll -- (2009 - present) • Chairman -- California Fair Political Practices Commission (2010-2011) • California Public Affairs Director – Edelman Public Relations (2007-2008) • Partner -- Command Focus Public Affairs (2003-2006) • Executive Director -- Center for Campaign Leadership (2001-2002) • Communications Director -- McCain for President 2000 (1999-2000) • Political Director -- Technology Network (1997-1998) • Adjunct Instructor -- UC-Berkeley (1996-2011) • Press Secretary -- Wilson for Governor (1994) • Communications Director -- Office of Governor Pete Wilson (1991-1994) • Communications Director -- California Republican Party (1990) • Deputy Press Secretary -- Republican National Committee (1989) • Field Communications Coordinator -- Bush-Quayle '88 (1987-1988) • Press Secretary -- Office of U.S. Congressman Ed Zschau (1986) • Press Assistant -- Office of U.S. Senator Paula Hawkins (1985) • Media Assistant -- Reagan-Bush '84 (1984) Dan Schnur is the Director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics at the University of Southern California, where he works to motivate students to become active in the world of politics and encourage public officials to participate in the daily life of USC. For years, Dan was one of California’s leading political and media strategists, whose record includes work on four presidential and three gubernatorial campaigns. Schnur served as -

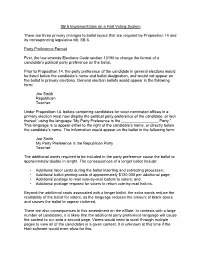

Proposition 14 Implementation on a Hart Voting System

SB 6 Implementation on a Hart Voting System There are three primary changes to ballot layout that are required by Proposition 14 and its corresponding legislative bill, SB 6. Party Preference Format First, the law amends Elections Code section 13150 to change the format of a candidate’s political party preference on the ballot. Prior to Proposition 14, the party preference of the candidate in general elections would be listed below the candidate’s name and ballot designation, and would not appear on the ballot in primary elections. General election ballots would appear in the following form: Joe Smith Republican Teacher Under Proposition 14, ballots containing candidates for voter-nominated offices in a primary election must now display the political party preference of the candidate, or lack thereof, using the language “My Party Preference is the _________________ Party.” This language is to appear either to the right of the candidate’s name, or directly below the candidate’s name. The information would appear on the ballot in the following form: Joe Smith My Party Preference is the Republican Party Teacher The additional words required to be included in the party preference cause the ballot to approximately double in length. The consequences of a longer ballot include: • Additional labor costs during the ballot inserting and extracting processes; • Additional ballot printing costs of approximately $120,000 per additional page; • Additional postage to mail vote-by-mail ballots to voters; and • Additional postage required for voters to return vote-by-mail ballots. Beyond the additional costs associated with a longer ballot, the extra words reduce the readability of the ballot for voters, as the language reduces the amount of blank space and causes the ballot to appear cluttered. -

Official Ballot June 3, 2014 Direct Primary Election San Luis Obispo County, California

OFFICIAL BALLOT JUNE 3, 2014 DIRECT PRIMARY ELECTION SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTERS: BT 4 To vote, fill in the oval like this: Vote both sides of the card. To vote for the candidate of your choice, fill in the OVAL next to the candidate's name. Do not vote for more than the number of candidates allowed (i.e. vote for no more than Two). To vote for a qualified write-in candidate, write in the candidate's full name on the Write-In line and fill in the OVAL next to it. To vote on a measure, fill in the OVAL next to the word "Yes" or the word "No". If you tear, deface or wrongly mark this ballot, return it to the Elections Official and get another. VOTER-NOMINATED AND NONPARTISAN OFFICES All voters, regardless of the party preference they disclosed upon registration, or refusal to disclose a party preference, may vote for any candidate for a voter-nominated or nonpartisan office. The party preference, if any, designated by a candidate for a voter-nominated office is selected by the candidate and is shown for the information of the voters only. It does not imply that the candidate is nominated or endorsed by the party or that the party approves of the candidate. The party preference, if any, of a candidate for a nonpartisan office does not appear on the ballot. STATE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR CONTROLLER Vote for One Vote for One GOVERNOR Vote for One ERIC KOREVAAR DAVID EVANS Party Preference: Democratic Party Preference: Republican ANDREW BLOUNT Scientist/Businessman/Parent Chief Financial Officer Party Preference: Republican Mayor/Businessperson DAVID FENNELL ASHLEY SWEARENGIN Party Preference: Republican Party Preference: Republican RAKESH KUMAR CHRISTIAN Entrepreneur Mayor, City of Fresno Party Preference: None Small Business Owner AMOS JOHNSON BETTY T. -

Video Games As Free Speech

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Video Games as Free Speech Benjamin Cirrinone University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cirrinone, Benjamin, "Video Games as Free Speech" (2014). Honors College. 162. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/162 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIDEO GAMES AS FREE SPEECH by Benjamin S. Cirrinone A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: James E.Gallagher, Associate Professor of Sociology Emeritus & Honors Faculty Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science/Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Mark Haggerty, Rezendes Professor for Civic Engagement, Honors College Copyright © 2014 Benjamin Cirrinone All rights reserved. This work shall not be reproduced in any form, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in review, without permission in written form from the author. Abstract The prevalence of video game violence remains a concern for members of the mass media as well as political actors, especially in light of recent shootings. However, many individuals who criticize the industry for influencing real-world violence have not played games extensively nor are they aware of the gaming community as a whole. -

Breaking the Bank Primary Campaign Spending for Governor Since 1978

Breaking the Bank Primary Campaign Spending for Governor since 1978 California Fair Political Practices Commission • September 2010 Breaking the Bank a report by the California Fair Political Practices Commission September 2010 California Fair Political Practices Commission 428 J Street, Suite 620 Sacramento, CA 95814 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Cost-per-Vote Chart 8 Primary Election Comparisons 10 1978 Gubernatorial Primary Election 11 1982 Gubernatorial Primary Election 13 1986 Gubernatorial Primary Election 15 1990 Gubernatorial Primary Election 16 1994 Gubernatorial Primary Election 18 1998 Gubernatorial Primary Election 20 2002 Gubernatorial Primary Election 22 2006 Gubernatorial Primary Election 24 2010 Gubernatorial Primary Election 26 Methodology 28 Appendix 29 Executive Summary s candidates prepare for the traditional general election campaign kickoff, it is clear Athat the 2010 campaign will shatter all previous records for political spending. While it is not possible to predict how much money will be spent between now and November 2, it may be useful to compare the levels of spending in this year’s primary campaign with that of previous election cycles. In this report, “Breaking the Bank,” staff of the Fair Political Practices Commission determined the spending of each candidate in every California gubernatorial primary since 1978 and calculated the actual spending per vote cast—in 2010 dollars—as candidates sought their party’s nomination. The conclusion: over time, gubernatorial primary elections have become more costly and fewer people turnout at the polls. But that only scratches the surface of what has happened since 19781. Other highlights of the report include: Since 1998, the rise of the self-funded candidate has dramatically increased the cost of running for governor in California. -

Glen Park News Fall 2011

GPN glen park news Fall 2011 The Newspaper of the Glen Park Association Volume 29, No. 3 www.glenparkassociation.org Glen Canyon Park Plan Moves Forward Picture Glen Canyon Park with a new playground and tennis courts, an accessi- ble trail leading directly into by the canyon, a new plaza and Bonnee native plants garden, and Waldstein repaired Recreation Center and bathrooms, roof and heat- Elizabeth ing system. Those are ele- Weise ments of the Glen Canyon The Glen Canyon Park Improvement Plan, a Park tennis conceptual plan to improve the park that courts, with won key approvals by the Recreation and eucalyptus Park Commission and Board of Supervi- trees beyond. sors this summer. A proposed The nonprofit Trust for Public Land, redesign of the which crafted the proposal with help from park would move City officials, neighbors and advocacy the tennis courts groups, received the mayoral-appointed and require the commission’s OK of the plan in August. cutting of the trees, a move Now the design team is working on ardently opposed a more detailed plan to be presented to by some. Glen Park this fall. Among the outstand- ing issues that must be resolved: Photo • The size of the playground and the by materials to be used to build it. Parents Elizabeth Weise want to make sure that the equipment is free of toxins. should the chainsaws be fired up. hillside—with connectors that make Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks • Proposed removal of the eucalyptus • Whether improved access between sense. A handicapped-accessible trail Bond approved by voters in 2008, and trees on the hill above the present ten- the top of the park and the School of the loop would be created along Alms Road $900,000 set aside by the City for trail nis courts. -

The Making of California's Framework, Standards, and Tests for History

“WHAT EVERY STUDENT SHOULD KNOW AND BE ABLE TO DO”: THE MAKING OF CALIFORNIA’S FRAMEWORK, STANDARDS, AND TESTS FOR HISTORY-SOCIAL SCIENCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Bradley Fogo July 2010 © 2010 by Bradley James Fogo. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/mg814cd9837 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Samuel Wineburg, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Labaree I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Milbrey McLaughlin Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements: I wish to thank my adviser Sam Wineburg for the invaluable guidance and support he provided on this project from its inception to the final drafting. -

W Pacific Citiroil

INSIDE PAGE 9 CoLTbm Sakaimito: MIS Nisei GIs feced aihird’ war WEiloUWwd I92« Pacific Citiroil Notkxxjl PubScaflon of the Japanese American Cittzans LBogue (JACL) >d (US.. Canj / $1 JO (Japan Air) 2822/ Vol. 124. No. 10 I i.'ioy i 6-June 5 i997 Mainland ties suspected in graffiti at Oahu cemeteries HONOLULU—Joint police and etery in Kaneohe, Gov. Ben FBI task forced collected evidence C^ayetano said as he was leaving a and analy^ the blood-red spray defaced col umbarian wall Sunday. graffiti which desecrated some 260 This desecration is the worst I grave markers at seven Oahu cem have ever seen. It’s outrageous. ” eteries and 22 walls of the The message on the wall read: columbarium at the Nati<mal Me “My love was greater that your morial Cemetery of the Pacific (the love. Now my hate is greater than Punchbowl ) during the nigh t hours your hate. HPD [Honolulu Police of April 19-20. Department] ignores hate crime. ^ j VV Police Capt. Doug Miller Let them ignore this tag ." Wednesday (April 23) said the in The same message on one marble vestigators believe the vandalism wall at the Punchbowl was signed: was done by a group of individuals, “We are Ps.A.R.I H- (Psychos po^bly with ties to the Mainland. Against Racism in Hawaii. T “Differences in handwriting would Police ChiefMichael Nakamursu indicate more than one individual promising Action, declared; “I will ri#-'' was involved," he felt. And since stick my ne^ out and say it will be there were seven sites involved in solved eventually.