California's Affirmative Action Fight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

110Th Congress 17

CALIFORNIA 110th Congress 17 CALIFORNIA (Population 2000, 33,871,648) SENATORS DIANNE FEINSTEIN, Democrat, of San Francisco, CA; born in San Francisco, June 22, 1933; education: B.A., Stanford University, 1955; elected to San Francisco Board of Super- visors, 1970–78; president of Board of Supervisors: 1970–71, 1974–75, 1978; mayor of San Francisco, 1978–88; candidate for governor of California, 1990; recipient: Distinguished Woman Award, San Francisco Examiner; Achievement Award, Business and Professional Women’s Club, 1970; Golden Gate University, California, LL.D. (hon.), 1979; SCOPUS Award for Out- standing Public Service, American Friends of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; University of Santa Clara, D.P.S. (hon.); University of Manila, D.P.A. (hon.), 1981; Antioch University, LL.D. (hon.), 1983; Los Angeles Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith’s Distinguished Serv- ice Award, 1984; French Legion d’Honneur from President Mitterand, 1984; Mills College, LL.D. (hon.), 1985; U.S. Army’s Commander’s Award for Public Service, 1986; Brotherhood/ Sisterhood Award, National Conference of Christians and Jews, 1986; Paulist Fathers Award, 1987; Episcopal Church Award for Service, 1987; U.S. Navy Distinguished Civilian Award, 1987; Silver Spur Award for Outstanding Public Service, San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association, 1987; All Pro Management Team Award for No. 1 Mayor, City and State Magazine, 1987; Community Service Award Honoree for Public Service, 1987; American Jew- ish Congress, 1987; President’s Award, St. Ignatius High School, San Francisco, 1988; Coro Investment in Leadership Award, 1988; President’s Medal, University of California at San Fran- cisco, 1988; University of San Francisco, D.H.L. -

President Richard Nixon's Daily Diary, May 16-31, 1973

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Air Force One – Appendix “B” 5/19/1973 A 2 Manifest Air Force One – Appendix “D” 5/25/1973 A 3 Log Key Biscayne, Florida – 6:40 p.m. – p 2 5/26/1973 A of 2 Sanitized 6/2000 OPENED 06/2013 4 Manifest Air Force One – Appendix “B” 5/28/1973 A 5 Manifest Air Force One – Appendix “B” 5/30/1973 A 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/19/1973 A Appendix “A” 7 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 5/20/1973 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-12 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary May 16, 1973 – May 31, 1973 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

December, 2015 Dan Schnur • Director -- Jesse M

December, 2015 Dan Schnur • Director -- Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics, University of Southern California (2008 – present) • Director -- USC Dornsife/LA Times Poll -- (2009 - present) • Chairman -- California Fair Political Practices Commission (2010-2011) • California Public Affairs Director – Edelman Public Relations (2007-2008) • Partner -- Command Focus Public Affairs (2003-2006) • Executive Director -- Center for Campaign Leadership (2001-2002) • Communications Director -- McCain for President 2000 (1999-2000) • Political Director -- Technology Network (1997-1998) • Adjunct Instructor -- UC-Berkeley (1996-2011) • Press Secretary -- Wilson for Governor (1994) • Communications Director -- Office of Governor Pete Wilson (1991-1994) • Communications Director -- California Republican Party (1990) • Deputy Press Secretary -- Republican National Committee (1989) • Field Communications Coordinator -- Bush-Quayle '88 (1987-1988) • Press Secretary -- Office of U.S. Congressman Ed Zschau (1986) • Press Assistant -- Office of U.S. Senator Paula Hawkins (1985) • Media Assistant -- Reagan-Bush '84 (1984) Dan Schnur is the Director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics at the University of Southern California, where he works to motivate students to become active in the world of politics and encourage public officials to participate in the daily life of USC. For years, Dan was one of California’s leading political and media strategists, whose record includes work on four presidential and three gubernatorial campaigns. Schnur served as -

SOHO Reflections Newsletter, Vol. 12, Issue 5

THE S.O.H.O. NEWSLETTER REFLECTIONS MAY 1980 P .O. BOX 3571 SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA 92103 (714)222-3148 National Preservation Week May I I._17 It's National Preservation Week again an annual time set aside to recognize outstanding preservation efforts, and to make more Americans and San Diegans! aware of the preservation movement and its contributions to the quality of life in every community. The theme of National Preservation Week, 1980 is "Preservation: Reusing America's Energy': and this year is co-sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy. The message is three-fold: 1) old buildings are a past investment of energy; 2) old buildings can be renovated for greater energy efficiency in their operation, and 3) new technology like solar power, for example, can be used in manv old buildings without destroying their historical and architectural cl--~racteristics. Look downtown this week at the Knights of Pythias Building at 3rd and E, which has housed the Community Arts complex, as a good example of adaptive reuse. Look at the Lyceum and Hor ton Hotels -- all freshly painted, and beautifully too. Gaslarnp is blooming, albeit too slowly for some, into a showy flower. All around us we see examples of positive preservation-- both public and private. Paul Thoryk's Soledad Franco Restaurant in the newly renovated Columbia Square is a showplace. Ted Krauss' offices at Front and Fir, an early-on example of preservation in action. Parker Industry's on-going rehabilitation in the spectacular Long Waterman House at First & Kalmia, and of course, the lovely new bed and breakfast remodel ling of the Britt House at Fourth & Maple. -

Breaking the Bank Primary Campaign Spending for Governor Since 1978

Breaking the Bank Primary Campaign Spending for Governor since 1978 California Fair Political Practices Commission • September 2010 Breaking the Bank a report by the California Fair Political Practices Commission September 2010 California Fair Political Practices Commission 428 J Street, Suite 620 Sacramento, CA 95814 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Cost-per-Vote Chart 8 Primary Election Comparisons 10 1978 Gubernatorial Primary Election 11 1982 Gubernatorial Primary Election 13 1986 Gubernatorial Primary Election 15 1990 Gubernatorial Primary Election 16 1994 Gubernatorial Primary Election 18 1998 Gubernatorial Primary Election 20 2002 Gubernatorial Primary Election 22 2006 Gubernatorial Primary Election 24 2010 Gubernatorial Primary Election 26 Methodology 28 Appendix 29 Executive Summary s candidates prepare for the traditional general election campaign kickoff, it is clear Athat the 2010 campaign will shatter all previous records for political spending. While it is not possible to predict how much money will be spent between now and November 2, it may be useful to compare the levels of spending in this year’s primary campaign with that of previous election cycles. In this report, “Breaking the Bank,” staff of the Fair Political Practices Commission determined the spending of each candidate in every California gubernatorial primary since 1978 and calculated the actual spending per vote cast—in 2010 dollars—as candidates sought their party’s nomination. The conclusion: over time, gubernatorial primary elections have become more costly and fewer people turnout at the polls. But that only scratches the surface of what has happened since 19781. Other highlights of the report include: Since 1998, the rise of the self-funded candidate has dramatically increased the cost of running for governor in California. -

The Making of California's Framework, Standards, and Tests for History

“WHAT EVERY STUDENT SHOULD KNOW AND BE ABLE TO DO”: THE MAKING OF CALIFORNIA’S FRAMEWORK, STANDARDS, AND TESTS FOR HISTORY-SOCIAL SCIENCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Bradley Fogo July 2010 © 2010 by Bradley James Fogo. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/mg814cd9837 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Samuel Wineburg, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Labaree I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Milbrey McLaughlin Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements: I wish to thank my adviser Sam Wineburg for the invaluable guidance and support he provided on this project from its inception to the final drafting. -

Chapter 8 - Executive Politics

CHAPTER 8 - EXECUTIVE POLITICS TEST BANK MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS 1. Diluted power, independent offices, and multiple avenues for group influence together give California’s executive branch its own form of A. pluralism. B. elitism. C. democracy. D. hyperpluralism. 2. The first governor to serve more than four years in the twentieth century was A. Milton Latham. B. Hiram Johnson. C. Frederick Low. D. Earl Warren. 3. The governor considered aloof and philosophical was A. Pete Wilson. B. Ronald Reagan. C. Earl Warren. D. Jerry Brown. 4. Which of the following is TRUE concerning California governors? A. They can utilize the item veto. B. They have brief “honeymoon” periods. C. They exercise “supreme executive power.” D. All of the above. 154 5. A governor’s personal staff is headed by a A. chief of staff. B. chief assistant. C. foreperson. D. chief operating officer. Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. 80 Chapter 8: Executive Politics 6. Governor Pat Brown reorganized numerous departments into A. still more departments. B. superagencies. C. a “kitchen” cabinet. D. a cabinet. 7. The internal budget process is dominated by the A. chief of staff. B. the governor. C. legislative analyst. D. Department of Finance. 8. In budget politics, the “Big Five” has shrunk to the “Big Three,” which refers to the governor and A. Assembly Speaker and his/her appointees. B. Senate Pro Tempore and his/her appointees. C. majority leader from each chamber. D. top officials in the Department of Finance. 9. Once the budget is passed, the governor has power of A. the legislative programs. -

Lessons from the Deukmejian Era for Contemporary California State Budgeting

FROM JERRYRIGGED TO PETERED OUT: LESSONS FROM THE DEUKMEJIAN ERA FOR CONTEMPORARY CALIFORNIA STATE BUDGETING Daniel J.B. Mitchell, UCLA HoSu Wu Professor of Management and Public Policy The new governor took office in the midst of a major state budget crisis. At the time he took office, it was unclear that state could pay its bills if drastic action were not taken. Yet the incoming governor was committed to a notaxincrease program. Through borrowing, the state managed to surmount its budget crisis. As the economy recovered and resulting tax revenue flowed in, it even was able to engage in major construction projects. When he stood for re election, the governor was overwhelmingly returned to office for a second term. Sadly, however, the economy began to slow during that second term. Fears mounted that the state could face a renewed budget crisis. This description may seem to depict the career to date of Arnold Schwarzenegger. He inherited a budget crisis from Gray Davis who he replaced in the 2003 recall. But the introductory vignette actually refers to the story of George Deukmejian (“Duke”) who was first elected in 1982, inheriting a budget crisis from Jerry Brown. (Deukmejian’s construction projects leaned towards prisons for most of his terms in office, needed as state sentencing laws tightened, rather than the roads and other infrastructure pushed by Schwarzenegger.) And as it turned out, the economic downturn that began to take shape towards the end of Deukmejian’s second term indeed did produce a major budget crisis, a legacy he left for his successor, Pete Wilson. -

The California Recall History Is a Chronological Listing of Every

Complete List of Recall Attempts This is a chronological listing of every attempted recall of an elected state official in California. For the purposes of this history, a recall attempt is defined as a Notice of Intention to recall an official that is filed with the Secretary of State’s Office. 1913 Senator Marshall Black, 28th Senate District (Santa Clara County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Herbert C. Jones elected successor Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Failed to qualify for the ballot 1914 Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Edwin I. Wolfe elected successor Senator James C. Owens, 9th Senate District (Marin and Contra Costa counties) Qualified for the ballot, officer retained 1916 Assemblyman Frank Finley Merriam Failed to qualify for the ballot 1939 Governor Culbert L. Olson Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Citizens Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1940 Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1960 Governor Edmund G. Brown Filed by Roderick J. Wilson Failed to qualify for the ballot 1 Complete List of Recall Attempts 1965 Assemblyman William F. Stanton, 25th Assembly District (Santa Clara County) Filed by Jerome J. Ducote Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman John Burton, 20th Assembly District (San Francisco County) Filed by John Carney Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman Willie L. -

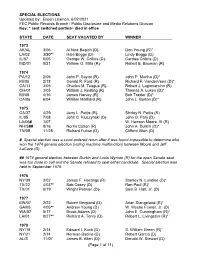

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

Congressional Directory CALIFORNIA

18 Congressional Directory CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA (Population 2000, 33,871,648) SENATORS DIANNE FEINSTEIN, Democrat, of San Francisco, CA; born in San Francisco, June 22, 1933; education: B.A., Stanford University, 1955; elected to San Francisco Board of Super- visors, 1970–78; president of Board of Supervisors: 1970–71, 1974–75, 1978; mayor of San Francisco, 1978–88; candidate for governor of California, 1990; recipient: Distinguished Woman Award, San Francisco Examiner; Achievement Award, Business and Professional Women’s Club, 1970; Golden Gate University, California, LL.D. (hon.), 1979; SCOPUS Award for Out- standing Public Service, American Friends of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; University of Santa Clara, D.P.S. (hon.); University of Manila, D.P.A. (hon.), 1981; Antioch University, LL.D. (hon.), 1983; Los Angeles Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith’s Distinguished Serv- ice Award, 1984; French Legion d’Honneur from President Mitterand, 1984; Mills College, LL.D. (hon.), 1985; U.S. Army’s Commander’s Award for Public Service, 1986; Brotherhood/ Sisterhood Award, National Conference of Christians and Jews, 1986; Paulist Fathers Award, 1987; Episcopal Church Award for Service, 1987; U.S. Navy Distinguished Civilian Award, 1987; Silver Spur Award for Outstanding Public Service, San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association, 1987; All Pro Management Team Award for No. 1 Mayor, City and State Magazine, 1987; Community Service Award Honoree for Public Service, 1987; American Jew- ish Congress, 1987; President’s Award, St. Ignatius High School, San Francisco, 1988; Coro Investment in Leadership Award, 1988; President’s Medal, University of California at San Fran- cisco, 1988; University of San Francisco, D.H.L.