Options in Teaching the Mahabharata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

The Mahabharata Twenty-Five Years Later

THE MAHABHARATA TWENTy-Five YEARS LATER Peter Brook in conversation with Jonathan Kalb t age eighty-five, Peter Brook does all he can to avoid interviews. He has no interest in his own legend, and as for his theatrical ideas, he has said it all before, in his autobiography (Threads of Time), in his other books (The AEmpty Space, The Shifting Point), and in the body of influential productions that established him as one of the giants of twentieth-century theatre. At the request of a common friend, he nevertheless kindly agreed to speak to me on the subject of his magnum opus, The Mahabharata—a focus of the book I was writing at the time (Great Lengths: Seven Marathon Plays from Three Decades, forthcoming). Brook was in New York rehearsing his adaptation of Mozart’s The Magic Flute at Lincoln Center and accompanying the Theatre for a New Audience presentation of Love is My Sin, his staging of Shakespeare sonnets. Although he announced in 2008 that he was giving up day-to-day operation of his theatre in Paris, Bouffes du Nord, he has been notably active. Among his other recent projects have been: Fragments, a program of five short pieces by Samuel Beckett; Athol Fugard’sSizwe Banzi is Dead; The Grand Inquisitor, adapted from Dostoyevsky; and Tierno Bokar, a parable about tolerance and fundamentalism rooted in a spiritual dispute among Sufis. The Mahabharata was Brook’s eleven-hour stage adaptation of the massive, epic cor- nerstone of Hindu literature, religion and culture, originally produced in French in 1985 and performed in English for a 1987 world tour that included the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Majestic Theatre (now The Harvey). -

Katyn Crime Had Been Committed

Katyń 80th anniversary a reminder of the crimes of Soviet Russia committed against Poles in 1937-1941 Created by: Andrzej Burghardt Zbigniew Koralewski Krzysztof Wąż © COPYRIGHT 2021 Coalition of Polish Americans Knowledge of the history of Poland, our country of origin, including the tragedies of which Katyn is a symbol, is an extremely important element of the sense of national community. For a numer of reasons, the history of Poland, especially the period of World War II, is distorted and deformed, also in the United States, so we must strive to learn the truth about these events. This presentation will acquaint you closer with: Polish Operation; secret protocol between Germany and Russia; Hitler's orders; methods of extermination of the Polish nation; the Katyn massacre; deportations of Poles to Siberia; hiding and falsifying the truth about the Katyn genocide and deportations to Siberia. Polish Operation by NKVD in 1937 „Polish Operation” was carried out by the NKVD (communist secret police) two years before the Second World War. It consisted in arresting of people of Polish origin who lived within the domain of Soviet Russia. According to the documents, almost 240,000 people were imprisoned at that time, of which almost half were murdered, the rest were sentenced to stay in labor camps or deported to Kazakhstan and Siberia. Victims of the NKVD „Polish Operation” The action covered all suspected of Polish origin. Poles were killed or deported for only one reason: because they were Poles. This served as a model for organizing later mass arrests, forced resettlements and murders such as in Katyn. -

Chapter Iv Data Analysis

CHAPTER IV DATA ANALYSIS Ramayana and Mahabharata are Wiracarita, the heroic stories which are well – known from one generation to another. These two great epics are originally written in Sanskrit. The author of Ramayana is Walmiki, and the author of Mahabharata is Bhagawan Wyasa. Ramayana and Mahabharata have been translated into various languages. In Indonesia, these two great epics have been retold in various versions such as Wayang kulit performance, dance, book, novel, and comic. For this research, the writer chooses the Mahabharata novel by Nyoman. S. Pendit. With the focus of the research on the heroic journey of Arjuna in this novel. In this chapter, the writer would like to answer and to analyze three problem formulations of this research. First, the writer would like to retell Arjuna‟s journey based on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel. After that, as the second problem formulation, the writer would like to compare to what extent the journey of Arjuna on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel fulfills the criteria of the Hero‟s Journey theory proposed by Joseph Campbell. The Hero‟s Journey theory itself consists of seventeen stages divided into three big stages: Departure – Initiation – Return. It can be seen from the journey of Arjuna in the Mahabharata novel by Nyoman. S. Pendit. After going through the several archetypal journey process framed in the Hero‟s Journey theory, Arjuna gets or shows the life virtues in himself. Therefore, as the third problem formulation, the 34 writer would like to mention what kind of life virtues showed by Arjuna on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel. -

2. a Superhit Goddess

Ganesh, lord of auspicious beginnings and father of goddess Santoshi Ma. A Superhit Goddess Jai Santoshi Maa and Caste Hierarchy in Indian Films Part One Philip Lutgendorf “Audiences were showering coins, perennials of its vast output, yet they quarter of national cinematic output) flower petals and rice at the screen constitute one of the least-studied enjoys the largest audience in appreciation of the film. They aspects of this comparatively under- throughout the Indian subcontinent entered the cinema barefoot and set studied cinema. Indeed, I will venture and beyond. Sholay (“Flames”) and up a small temple outside…. In that for scholars and critics, Deewar (“The Wall”), were both Bandra, where mythological films mythologicals have generally been heavily-promoted “multi-starrers” aren’t shown, it ran for fifty weeks. It “hard to see.” Yet DeMille’s words belonging to the then-dominant genre was a miracle”. —Anita Guha, also belie the fact that most sometimes referred to as the masala (actress who played goddess mythologicals—like most commercial (“spicy”) film: a multi-course cinematic Santoshi Ma; cited in Kabir films of any genre—flop at the box banquet incorporating suspenseful office. The comparatively few that drama, romance, comedy, violent 2001:115). have enjoyed remarkable and action sequences, and song and Genre, Film & Phenomenon sustained acclaim hence merit study dance. Both were expensive and Cecil B. DeMille’s famously both as religious expressions and as slickly made by the standards of the cynical adage, “God is box office,” successful examples of popular art and industry, and both featured Amitabh may be applied to Indian popular entertainment. -

Portrayal of Family Ties in Ancient Sanskrit Plays: a Study

Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Portrayal of Family Ties in Ancient Sanskrit Plays: A Study Dr. C. S. Srinivas Assistant Professor of English Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Technology Hyderabad India Abstract The journey of the Indian dramatic art begins with classical Sanskrit drama. The works of the ancient dramatists Bhasa, Kalidasa, Bhavabhuti and others are the products of a vigorous creative energy as well as sustained technical excellence. Ancient Sanskrit dramatists addressed several issues in their plays relating to individual, family and society. All of them shared a common interest— familial and social stability for the collective good. Thus, family and society became their most favoured sites for weaving plots for their plays. Ancient Sanskrit dramatists with their constructive idealism always portrayed harmonious filial relationships in their plays by persistently picking stories from the two great epics Ramayana and Mahabharata and puranas. The paper examines a few well-known ancient Sanskrit plays and focuses on ancient Indian family life and also those essential human values which were thought necessary and instrumental in fostering harmonious filial relationships. Keywords: Family, Filial, Harmonious, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Sanskrit drama. _______________________________________________________________________ http://www.ijellh.com 224 Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 The ideals of fatherhood and motherhood are cherished in Indian society since the dawn of human civilization. In Indian culture, the terms ‘father’ and ‘mother’ do not have a limited sense. ‘Father’ does not only mean the ‘male parent’ or the man who is the cause of one’s birth. In a broader sense, ‘father’ means any ‘elderly venerable man’. -

Buddhacarita

CLAY SANSKRIT LIBRARY Life of the Buddka by AsHvaghosHa NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS & JJC EOUNDATION THE CLAY SANSKRIT LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JOHN & JENNIFER CLAY GENERAL EDITORS RICHARD GOMBRICH SHELDON POLLOCK EDITED BY ISABELLE ONIANS SOMADEVA VASUDEVA WWW.CLAYSANSBCRITLIBRARY.COM WWW.NYUPRESS.ORG Copyright © 2008 by the CSL. All rights reserved. First Edition 2008. The Clay Sanskrit Library is co-published by New York University Press and the JJC Foundation. Further information about this volume and the rest of the Clay Sanskrit Library is available at the end of this book and on the following websites: www.ciaysanskridibrary.com www.nyupress.org ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-6216-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-6216-6 (cloth : alk. paper) Artwork by Robert Beer. Typeset in Adobe Garamond at 10.2$ : 12.3+pt. XML-development by Stuart Brown. Editorial input from Linda Covill, Tomoyuki Kono, Eszter Somogyi & Péter Szântà. Printed in Great Britain by S t Edmundsbury Press Ltd, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on acidffee paper. Bound by Hunter & Foulis, Edinburgh, Scotland. LIFE OF THE BUDDHA BY ASVAGHOSA TRANSLATED BY PATRICK OLIVELLE NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS JJC FOUNDATION 2008 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Asvaghosa [Buddhacarita. English & Sanskrit] Life of the Buddha / by Asvaghosa ; translated by Patrick Olivelle.— ist ed. p. cm. - (The Clay Sanskrit library) Poem. In English and Sanskrit (romanized) on facing pages. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-6216-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-6216-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Gautama Buddha-Poetry. I. Olivelle, Patrick. II. -

The Mahabharata

VivekaVani - Voice of Vivekananda THE MAHABHARATA (Delivered by Swami Vivekananda at the Shakespeare Club, Pasadena, California, February 1, 1900) The other epic about which I am going to speak to you this evening, is called the Mahâbhârata. It contains the story of a race descended from King Bharata, who was the son of Dushyanta and Shakuntalâ. Mahâ means great, and Bhârata means the descendants of Bharata, from whom India has derived its name, Bhârata. Mahabharata means Great India, or the story of the great descendants of Bharata. The scene of this epic is the ancient kingdom of the Kurus, and the story is based on the great war which took place between the Kurus and the Panchâlas. So the region of the quarrel is not very big. This epic is the most popular one in India; and it exercises the same authority in India as Homer's poems did over the Greeks. As ages went on, more and more matter was added to it, until it has become a huge book of about a hundred thousand couplets. All sorts of tales, legends and myths, philosophical treatises, scraps of history, and various discussions have been added to it from time to time, until it is a vast, gigantic mass of literature; and through it all runs the old, original story. The central story of the Mahabharata is of a war between two families of cousins, one family, called the Kauravas, the other the Pândavas — for the empire of India. The Aryans came into India in small companies. Gradually, these tribes began to extend, until, at last, they became the undisputed rulers of India. -

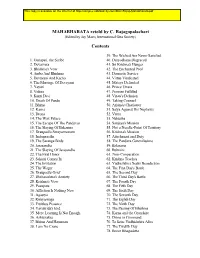

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Cinéma En Plein Air VII Édition I MICHEL PICCOLI Jardins, 8-19 Juillet 2013

Cinéma en plein air VII édition I MICHEL PICCOLI Jardins, 8-19 juillet 2013 L’édition 2013 du Cinéma en plein air rend un hommage exceptionnel à Michel Piccoli, immense artiste de l’histoire et de l’actualité du cinéma, avec un ensemble de films avec lui et de lui. Choisis avec sa collaboration, ceux-ci mettront particulièrement en valeur le rôle crucial joué par Michel Piccoli dans le cinéma européen. En parcourant l’histoire du cinéma français, il est difficile de trouver un acteur de la même étoffe que Michel Piccoli. Sa carrière cinématographique riche et diversifiée a vu l'acteur français jouer dans plus de deux cents films, qui ont donné lieu à des rencontres avec les plus grands réalisateurs transalpins et d'Italie, dans des rôles mémorables. Acteur de théâtre et de cinéma, Michel Piccoli interprète avec justesse et invention les rôles les plus complexes et opposés, s’adaptant aux univers et aux langages cinématographiques les plus divers. Artiste de renommée internationale, on le retrouve dans les films de Demy, Rivette, Sautet, Buñuel, Rouffio, Ferreri, Petri, Bellocchio, Hitchcock, Skolimowski, Doillon, Carax, Malle, Chabrol, Deville, Renoir, Godard, Lelouch, Granier-Deferre, Tavernier, Chahine, Resnais... Acteur de génie, il a également réalisé des films importants. Son étonnante capacité à investir ses rôles, à travailler dans la recherche et le mouvement continus, font de Michel Piccoli une véritable icône du cinéma. Du lundi 8 au vendredi 19 juillet pour le Cinéma en plein air l'Académie de France à Rome ouvre une fois de plus les jardins de la Villa Médicis, dont la salle de cinéma porte déjà le nom de Michel Piccoli. -

URUBHANGAM (BREAKING of THIGHS) – a TRAGEDY in INDIAN TRADITION Bhagvanbhai H.Chaudhari, Ph. D. Assoc. Professor, Dept. Of

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ DR. BHAGVANBHAI H. CHAUDHARI (5683-5688) URUBHANGAM (BREAKING OF THIGHS) – A TRAGEDY IN INDIAN TRADITION Bhagvanbhai H.Chaudhari, Ph. D. Assoc. Professor, Dept. of English, The KNSBL Arts and Commerce College, Kheralu Gujarat (India) Scholarly Research Journal's is licensed Based on a work at www.srjis.com By and large a play is considered an „imitation of folk-attitude‟ wherein the outcome of human activity may either be happy or unhappy. Since the time of ancient Greek literature in the West, the drama has been categorized as comedy and tragedy. But Bharat Muni in his Natyashastra projected it to be: (एतद्रसेषु भावेषु सववकमवक्रियास्वथ । सवोऩदेशजननं ना絍यं ऱोके भववष्यतत ॥ ) दԃु खातावनां श्रमातावनां शोकातावनां तऩस्स्वनाम ्। ववश्रास्ततजननं काऱे ना絍यमेतद्भववष्यतत ॥ ११४॥ धर्म्यं यशस्यमायुष्यं हहतं बुविवववधनव म ् । ऱोकोऩदेशजननं ना絍यमेतद्भववष्यतत ॥ ११५॥ ( १) i.e. It will [also] give relief to unlucky persons who are afflicted with sorrow and grief or [over]-work, and will be conducive to observance of duty(dharma) as well as to fame, long life, intellect and general good, and will educate people. (Ghosh 15) Further, he explains the concept and the significance of drama as ईश्वराणां ववऱासश्च स्थैयं दԃु खाहदवतस्य च । अथोऩजीववनामथो धतृ त셁饍वेगचते साम ्॥ १११॥ MAY-JUNE 2017, VOL- 4/31 www.srjis.com Page 5683 SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ DR. BHAGVANBHAI H. CHAUDHARI (5683-5688) नानाभावोऩसर्म्ऩतनं नानावस्थाततरा配मकम ्। ऱोकव配ृ तानुकरणं ना絍यमेततमया कृ तम ्॥ ११२॥ i.e. -

Discernment: the Message of the Bhagavad-Gita

Acta Theologica 2013 Suppl 17: 271-290 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v32i2S.14 ISSN 1015-8758 © UV/UFS <http://www.ufs.ac.za/ActaTheologica> K. Perumpallikunnel DISCERNMENT: THE MESSAGE OF THE BHAGAVAD-GITA ABSTRACT The Bhagavad-Gita is an intelligent response to a perennial human predicament which other religions and philosophies also tried to resolve in their own way. Human beings often stood perplexed and mystified as they confronted paradoxical situations in life that demanded action. Discerning right from wrong often became an existential predicament. The Pandava prince Arjuna found himself standing on the shaky ground of Kurukshetra not knowing the way forward. Lord Krishna outlines for him the path towards gaining flawless self-knowledge and self-mastery from his sorrowful state of confusion and opened his eyes to perceive the truths beyond appearances. Krishna instructs him that, when a person is capable of watching everything that happens within and around him dispassionately and acting with an attitude of detachment, he attains sthithaprajna (equanimity) and samadhai (liberation). 1. INTRODUCTION The subject matter of the Bhagavad-Gita (The song of God) is nothing other than discernment (Ramacharaka 2010:3). According to the Gita, discernment is all about nityanithya vastu viveka (discernment of the eternal and temporal realities) (Kaji 2001:27). Lord Krishna, the supreme Guru, tutors his confused disciple, Arjuna, to lead him from the state of maya (illusion) to the perfect understanding of satyasya satyam (really real). Krishna outlines for Arjuna the path towards gaining flawless self- knowledge and self-mastery from his sorrowful state of confusion (1:47).