2. a Superhit Goddess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata Twenty-Five Years Later

THE MAHABHARATA TWENTy-Five YEARS LATER Peter Brook in conversation with Jonathan Kalb t age eighty-five, Peter Brook does all he can to avoid interviews. He has no interest in his own legend, and as for his theatrical ideas, he has said it all before, in his autobiography (Threads of Time), in his other books (The AEmpty Space, The Shifting Point), and in the body of influential productions that established him as one of the giants of twentieth-century theatre. At the request of a common friend, he nevertheless kindly agreed to speak to me on the subject of his magnum opus, The Mahabharata—a focus of the book I was writing at the time (Great Lengths: Seven Marathon Plays from Three Decades, forthcoming). Brook was in New York rehearsing his adaptation of Mozart’s The Magic Flute at Lincoln Center and accompanying the Theatre for a New Audience presentation of Love is My Sin, his staging of Shakespeare sonnets. Although he announced in 2008 that he was giving up day-to-day operation of his theatre in Paris, Bouffes du Nord, he has been notably active. Among his other recent projects have been: Fragments, a program of five short pieces by Samuel Beckett; Athol Fugard’sSizwe Banzi is Dead; The Grand Inquisitor, adapted from Dostoyevsky; and Tierno Bokar, a parable about tolerance and fundamentalism rooted in a spiritual dispute among Sufis. The Mahabharata was Brook’s eleven-hour stage adaptation of the massive, epic cor- nerstone of Hindu literature, religion and culture, originally produced in French in 1985 and performed in English for a 1987 world tour that included the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Majestic Theatre (now The Harvey). -

Chapter Iv Data Analysis

CHAPTER IV DATA ANALYSIS Ramayana and Mahabharata are Wiracarita, the heroic stories which are well – known from one generation to another. These two great epics are originally written in Sanskrit. The author of Ramayana is Walmiki, and the author of Mahabharata is Bhagawan Wyasa. Ramayana and Mahabharata have been translated into various languages. In Indonesia, these two great epics have been retold in various versions such as Wayang kulit performance, dance, book, novel, and comic. For this research, the writer chooses the Mahabharata novel by Nyoman. S. Pendit. With the focus of the research on the heroic journey of Arjuna in this novel. In this chapter, the writer would like to answer and to analyze three problem formulations of this research. First, the writer would like to retell Arjuna‟s journey based on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel. After that, as the second problem formulation, the writer would like to compare to what extent the journey of Arjuna on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel fulfills the criteria of the Hero‟s Journey theory proposed by Joseph Campbell. The Hero‟s Journey theory itself consists of seventeen stages divided into three big stages: Departure – Initiation – Return. It can be seen from the journey of Arjuna in the Mahabharata novel by Nyoman. S. Pendit. After going through the several archetypal journey process framed in the Hero‟s Journey theory, Arjuna gets or shows the life virtues in himself. Therefore, as the third problem formulation, the 34 writer would like to mention what kind of life virtues showed by Arjuna on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel. -

The Mahabharata

VivekaVani - Voice of Vivekananda THE MAHABHARATA (Delivered by Swami Vivekananda at the Shakespeare Club, Pasadena, California, February 1, 1900) The other epic about which I am going to speak to you this evening, is called the Mahâbhârata. It contains the story of a race descended from King Bharata, who was the son of Dushyanta and Shakuntalâ. Mahâ means great, and Bhârata means the descendants of Bharata, from whom India has derived its name, Bhârata. Mahabharata means Great India, or the story of the great descendants of Bharata. The scene of this epic is the ancient kingdom of the Kurus, and the story is based on the great war which took place between the Kurus and the Panchâlas. So the region of the quarrel is not very big. This epic is the most popular one in India; and it exercises the same authority in India as Homer's poems did over the Greeks. As ages went on, more and more matter was added to it, until it has become a huge book of about a hundred thousand couplets. All sorts of tales, legends and myths, philosophical treatises, scraps of history, and various discussions have been added to it from time to time, until it is a vast, gigantic mass of literature; and through it all runs the old, original story. The central story of the Mahabharata is of a war between two families of cousins, one family, called the Kauravas, the other the Pândavas — for the empire of India. The Aryans came into India in small companies. Gradually, these tribes began to extend, until, at last, they became the undisputed rulers of India. -

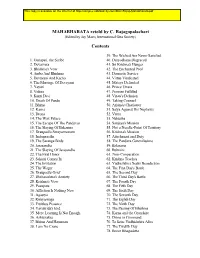

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Unit 2 Radio, Television and Cinema

UNIT 2 RADIO, TELEVISION AND CINEMA 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Origin and Development of Radio in India 2.2.1 The Indian Broadcasting Company 2.2.2 All India Radio 2.2.3 First Three Plans 2.2.4 Chanda Committee 2.25 Code for Broadcasteis 2.2.6 Verghese Committee 2.2.7 The Present Status 1 2.2.8 Audiena Research I 2.2.9 Radio's Effectiveness 23 Origin and Deveiopment of Television in India Ii I 2.3.1 TV Comes to India 2.3.2 SITE 2.3.3 Commercial Servia I 2.3.4 National Broadcest Trust I 23.5 Development in the Eighties 2.3.6 Joshi Committee ! 2.3.7 Video Boom 2.3.8 Cable TV 2.3.9 Effectiveness of Doordarshan 2.4 Origin and Development of Films in India 2.4.1 The Beginning 2.4.2 Film mesto India 2.4.3 The Silent Era 2.4.4 The Talkie 2.4.5 Government Oiganizations 2.4.6 Need for Good Films 2.5 Let Us Sum Up 2.6 Glossary 2.7 Further Reading 2.8 Check Your Pmgms : Model Answers 2.0' OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you should be able to : trace the development of radio, TV and film over the yeam ae a media of maw cbmrnunication; describe the reach and effectiveness of mdio, TV and film as media of mass communication; compare the development of radio, TV and film in India. 2.1 INTRODUCTION In unit 1 we traced the origin and development of the Indian press. -

Discernment: the Message of the Bhagavad-Gita

Acta Theologica 2013 Suppl 17: 271-290 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v32i2S.14 ISSN 1015-8758 © UV/UFS <http://www.ufs.ac.za/ActaTheologica> K. Perumpallikunnel DISCERNMENT: THE MESSAGE OF THE BHAGAVAD-GITA ABSTRACT The Bhagavad-Gita is an intelligent response to a perennial human predicament which other religions and philosophies also tried to resolve in their own way. Human beings often stood perplexed and mystified as they confronted paradoxical situations in life that demanded action. Discerning right from wrong often became an existential predicament. The Pandava prince Arjuna found himself standing on the shaky ground of Kurukshetra not knowing the way forward. Lord Krishna outlines for him the path towards gaining flawless self-knowledge and self-mastery from his sorrowful state of confusion and opened his eyes to perceive the truths beyond appearances. Krishna instructs him that, when a person is capable of watching everything that happens within and around him dispassionately and acting with an attitude of detachment, he attains sthithaprajna (equanimity) and samadhai (liberation). 1. INTRODUCTION The subject matter of the Bhagavad-Gita (The song of God) is nothing other than discernment (Ramacharaka 2010:3). According to the Gita, discernment is all about nityanithya vastu viveka (discernment of the eternal and temporal realities) (Kaji 2001:27). Lord Krishna, the supreme Guru, tutors his confused disciple, Arjuna, to lead him from the state of maya (illusion) to the perfect understanding of satyasya satyam (really real). Krishna outlines for Arjuna the path towards gaining flawless self- knowledge and self-mastery from his sorrowful state of confusion (1:47). -

A Summary of the Mahabharata

A Summary of The Mahabharata by Aneeta Sundararaj (heavily augmented by Amy Allison) http://www.homehighlight.org/humanities-and-science/cultures/a-summary-of-the-mahabharata.html The Mahabharata is an epic that comprises one hundred thousand stanzas of verse divided into eighteen books, or parvas. It is the largest single literary work in existence. Originally composed in the ancient language of Sanskrit sometime between 400 BC and 400 AD, it is set in a legendary era thought to correspond to the period of Indian culture and history in approximately the tenth century BC. The original “author” was Vyasa who tried to tell about the Great War between the Pandavas and the Kauravas - cousins who claimed to be the rightful rulers of a kingdom. The background to get to where the epic starts is very confusing (in medias res). I’ll present the background a bit here just to lay the groundwork. Background King Santanu married a strange woman he found by the river. They had many children and she drowned all of them (I told you she was strange). The king stopped her from downing the last child (a boy). She then said she was a goddess and that this child was a god but had to remain on earth as punishment for stealing a sacred cow in a past life. The child was named Devavratha, but to confuse you he is called Bhishma (one of firm vow). The goddess went back to wherever it is that goddesses go, and the king continued ruling. One day he fell in love with a woman who ran a ferry; her name was Satyavathi. -

Yakshagana Plays Based on Mahabharata

Yakshagana Plays Based on Mahabharata No Prasanga Name Author 1. Akshayambara Vilasa Thalengala Shambhatta 2. Anusalva Garva Bhanga matthu Niladhwajana Kalaga Ajjana Gaddhe Shankaranarayana 3. Abhaya Pradhana Dr D Sadashiva Bhatta 4. Abhimanyu Kalaga matthu Saindhava Vadhe 5. Abhimanyu Kalaga Parameshwara 6. Abhimanyu Kalaga Venkatesha V Pai 7. Ashwaththama Kiriya Balipa Narayana Bhagavatha 8. Ashwamedha Jwale Hosthota Manjunatha Bhagavatha 9. Ashwamedha Parva Kudreppadi Ishwara 10. Ashwamedha Parva Shivarama Hegade Bale Gaddhe 11. Adhiparva Sam. M. V. Hegade 12. Indrakeelaka Vishnu Ramaputra 13. Indhrakeelaka Devidasa 14. Uttharada Paurusha Puttanna, Mangalore 15. Uddhalaka Sheni Gopalakrishna Bhat [or Vishma Dampatya] 16. Ubhaya kula Billoja Bottakere Purushottama Poonja 17. Ekalavya Pandeshwara Kadappa 18. Ekalavya Hosthota Manjunatha Bhatta 19. Eni Bandhana Panduranga Ananta Shenoy 20. Airavata Parthisubba 21. Kanakangi Kalyana Nityananda Avadhoota 22. Karna Kshama Yachana Babu Kudthadka [Or Drona Senadhipatya] 23. Karna Pattabhisheka Seethanadi Ganapayya Shetty 24. Karna Parva Gerasoppe Shanth(ppa)yya 25. Karna Parva Venkatachala Bhatta,Keremane 26. Karna Ratnavathi M G Baravani 27. Karnarjunara Kalaga Venkata 28. Kitnaraja Parsango Badakabailu Parameshwarayya 29. Keechaka Vadham Naraharikeshava Bhatta, Chipageri 30. Kunti Swayamvara Seetanadhi Ganapayya Shetty 31. Kurukshetra Adura Balakila Vishnayya 32. Krishna Garudi Kota Srinivasa Nayaka 33. Krishnarjunara Kalaga Halemakkirama 34. Krishnarjunara Kalaga Mulki Ramakrishna 35. Krishnarjunara Kalaga Peruvadi Sankayya Bhagavata 36. Krishnarjunara Kalaga Balipa Narayana Bhagavata 37. Khandava Vana Dahana Ajjana Gadde Ganapayya Bhagavata 38. Gandugali Bhimasena Seetandi Ganapayya Shetty 39. Gadhaparva Subbanna Shastri, Chakrakodi 40. Gadhaparva Balipa Narayana Bhagavatha 41. Gandhari Anantaram Bangadi 42. Geetopadesha Malpe Ramadasa Samaga 43. Guru Drona Korgi Suryanarayana Upadhyaya 44. Ghatotkacha Janma M G Baravani 45. -

International Multidisciplinary Peer-Reviewed Journal ISSN: Print: 2347-5021 ISSN: Online: 2347-503X

Research Chronicler: International Multidisciplinary Peer-Reviewed Journal ISSN: Print: 2347-5021 www.research-chronicler.com ISSN: Online: 2347-503X The Vision of Darkness in Andha Yug Basavaraj Naikar Professor & Chairman, Department of English, Karnatak University, Dharwad, Karnataka, India Dharmavir Bharati (1926-97) the Hindi convey. Thus the premiere had to wait till author was born in Allahabad, Uttar 1962, produced by Satyadev Dubey on Pradesh. He studied there and participated Theatre Unit‘s rooftop stage in Bombay. in the anti-British Quit India movement. Subsequently the National School of He earned a doctorate in Siddha saint Drama performed it in 1963, directed by literature in 1947, and then became a full- Alkazi, and revived it several times. Many time journalist, editing the weekly directors in other languages, like Ajitesh DharmaYug from 1960 to 1989. His Bandyopadhyay (Bengali, 1970) and Ratan journal was a war correspondent in Thiyam (Manipuri, 1993), also staged Bangladesh in 1971, made a tremendous important versions.‖ 1 impact. He was also a poet, novelist and His play, Andha Yug, translated into essayist. His two novels, Gunahonka English by Alok Bhalla, deals with the Devata (The God of Sins) and Suraj Ka epical theme of the conflict between the Satvan Ghoda (The Seventh Horse of the Kauravas and the Pandavas culminating Sun) are classics of Hindi literature. He into climax on the eighteenth day of has published five one-act plays under the Kurukshetra war. Although the theme is title Nadi Pyasi Thi (The River was borrowed from the last part of Vyasa‘s Thirsty, 1954), often produced by schools, Mahabharata, Dharmavir Bharati has colleges and amateur groups. -

Download Download

The Taming of Alii1 Vijaya Ramaswamy ABSTRACT The story of Alii figures in the Tamil version of the Mahabharata. She is described as a type of "Amazonian" beauty, a vehement hater of men. In the zigzag movement of the Alii legend through space and time, the heroine Alii as well as the Alii myth get tamed and subsumed into the patriarchal register. RESUME L'histoire d'Alli figure dans la version tamile de Mahabharata. Elle est decrite comme un genre de beaute "amazonienne," une femme qui a une haine vehemente envers les hommes. Dans le zigzag de la legende d'Alli a travers l'espace et le temps, l'heroi'ne Alii ainsi que le mythe d'Alli sont apprivoises et subsumes dans le registre patriarcal. Myths and legends are not frozen in time. dramatised versions of Alii both on stage and on This article looks at the changing perceptions of screen. The available multiple texts, however, by women in Tamil society and the imaging of Tamil and large represent the voice of patriarchy. women within the male patriarchal register, Although the nature and content of the Alii myth(s) focusing on the transformational qualities of myths. suggest a non-patriarchal origin, there are no extant I contextualize some leading Tamil myths that are versions that have not been diluted by "patriarchal women-centred in terms of their historical and taming." Therefore the recovery of the geographical specificity. A critical study of such a non-patriarchal Alii has to be done by fragmenting leading Tamil myth - the legend of Alii - the mega-narrative of the "Mahabharata Alii" and demonstrates the gradual process by which an examining the sub-text of these versions. -

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Agnatavasa of Pandavas the Events

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Agnatavasa of Pandavas The events of Virataparva that relate to the agnatavasa of Pandavas are described in 23rd chapter. After completing the twelve years period of Vanavasa Pandavas took leave of Dhaumya, other sages and Brahman’s and made up their mind to undergo agnatavasa. They went to capital city of Virata. Before they entered the city they hid their weapons on a Sami tree in the outskirts of the city. The five Pandavas assumed the form of an ascetic, a cook, a eunuch, a charioteer, and a cowherd respectively. Draupadi assumed the form of Sairandhri i.e. a female artisan. Bhima assumed the form of cook for two reasons i) He never took food prepared by others ii) He did not want to reveal his great knowledge by assuming a Brahmana form. During their Agnatavasa they did not serve Virata or any other person. The younger brothers of Yudhishtira served Lord Hari and their eldest brother Yudhishtira in whom also God was present by the name of Yudhishtira One day a wrestler who had become invincible by the boon of Siva came to Virata's city. The wrestlers maintained by Virata were not able to meet his challenge. The ascetic i.e.Yudhishtira suggested to king Virata that the cook who had the skill in wrestling well could be asked to wrestle with him. The cook i.e., Bhima, wrestled with him and killed. Kichaka is Killed Ten months after Pandava's stay at Virata's palace, Kichaka, the brother of Queen Sudesna came. He was away to conquer the neighboring kings. -

A Fresh Perspective on the Astronomy of the Mahabharata

ISBN: 978-1-9051860-1-3 © Dr Manish Pandit 2019 !ii Dedicated To My Gurus and Divine Mother Kali !i Foreword 3067BCE: A Fresh Perspective on the Astronomy of the Mahabharata I made the film “Krishna: History or Myth” in 2008 after a set of severe arguments on the subject of the historicity of Sri Krishna and Sri Rama, one of which was with a junior doctor when working as a surgeon in 2002 in the West Midlands. I had come across several pieces of research which claimed to corroborate the astronomy of the Mahabharata war. Amongst these were the research by PV Vartak, (5561BCE) a senior MBBS doctor residing in Pune who I have had the pleasure of meeting years ago in Pune, the research by Dr Narahari Achar from Memphis (3067BCE), Balakrishna and Sengupta (2449BCE) among others. I never wanted to really make a film on the subject, but nobody else was willing, partly due to the cost involved in the shooting of such a film (those were the days when digital film cameras were only just about becoming affordable) and of the course nobody wanted to take the risk of making a film which most Indian, English language, Hinduphobic channels would not show. I also had to check and see which piece of research was actually true: 5561BCCE, 3067BCE, 3139BCE, 3043BCE or indeed 1478BCE or 2449BCE among others. It took me a lot of time to go through the various pieces of research from 2004 to 2007 and eventually after taking great care to !ii exclude the wrong pieces of research, I sat down and corroborated the research on Redshift.