I. Buchler Measuring the Development of Kinship Terminologies: Scalogram and Transformational Accounts of Omaha-Type Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Cultural Anthropology and British Social Anthropology

Anthropology News • January 2006 IN FOCUS ANTHROPOLOGY ON A GLOBAL SCALE In light of the AAA's objective to develop its international relations and collaborations, AN invited international anthropologists to engage with questions about the practice of anthropology today, particularly issues of anthropology and its relationships to globaliza- IN FOCUS tion and postcolonialism, and what this might mean for the future of anthropology and future collaborations between anthropologists and others around the world. Please send your responses in 400 words or less to Stacy Lathrop at [email protected]. One former US colleague pointed out American Cultural Anthropology that Boas’s four-field approach is today presented at the undergradu- ate level in some departments in the and British Social Anthropology US as the feature that distinguishes Connections and Four-Field Approach that the all-embracing nature of the social anthropology from sociology, Most of our colleagues’ comments AAA, as opposed to the separate cre- highlighting the fact that, as a Differences German colleague noted, British began by highlighting the strength ation of the Royal Anthropological anthropologists seem more secure of the “four-field” approach in the Institute (in 1907) and the Associa- ROBERT LAYTON AND ADAM R KAUL about an affinity with sociology. US. One argued that this approach is tion of Social Anthropologists (in U DURHAM Clearly British anthropology traces in fact on the decline following the 1946) in Britain, contributes to a its lineage to the sociological found- deeper impact that postmodernism higher national profile of anthropol- ing fathers—Durkheim, Weber and consistent self-critique has had in the US relative to the UK. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Kinship Terminology

Fox (Mesquakie) Kinship Terminology IVES GODDARD Smithsonian Institution A. Basic Terms (Conventional List) The Fox kinship system has drawn a fair amount of attention in the ethno graphic literature (Tax 1937; Michelson 1932, 1938; Callender 1962, 1978; Lounsbury 1964). The terminology that has been discussed consists of the basic terms listed in §A, with a few minor inconsistencies and errors in some cases. Basically these are the terms given by Callender (1962:113-121), who credits the terminology given by Tax (1937:247-254) as phonemicized by CF. Hockett. Callender's terms include, however, silent corrections of Tax from Michelson (1938) or fieldwork, or both. (The abbreviations are those used in Table l.)1 Consanguines Grandparents' Generation (1) nemesoha 'my grandfather' (GrFa) (2) no hkomesa 'my grandmother' (GrMo) Parents' Generation (3) nosa 'my father' (Fa) (4) nekya 'my mother' (Mo [if Ego's female parent]) (5) nesekwisa 'my father's sister' (Pat-Aunt) (6) nes'iseha 'my mother's brother' (Mat-Unc) (7) nekiha 'my mother's sister' (Mo [if not Ego's female parent]) 'Other abbreviations used are: AI = animate intransitive; AI + O = tran- sitivized AI; Ch = child; ex. = example; incl. = inclusive; m = male; obv. = obviative; pi. = plural; prox. = proximate; sg. = singular; TA = transitive ani mate; TI-0 = objectless transitive inanimate; voc. = vocative; w = female; Wi = wife. Some citations from unpublished editions of texts by Alfred Kiyana use abbreviations: B = Buffalo; O = Owl (for these, see Goddard 1990a:340). 244 FOX -

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean Prepared by: Dr. Godfrey St. Bernard The University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Phone Contacts: 1-868-776-4768 (mobile) 1-868-640-5584 (home) 1-868-662-2002 ext. 2148 (office) E-mail Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] Prepared for: United Nations Division of Social Policy and Development Department of Economic and Social Affairs Program on the Family Date: May 23, 2003 Introduction Though an elusive concept, the family is a social institution that binds two or more individuals into a primary group to the extent that the members of the group are related to one another on the basis of blood relationships, affinity or some other symbolic network of association. It is an essential pillar upon which all societies are built and with such a character, has transcended time and space. Often times, it has been mooted that the most constant thing in life is change, a phenomenon that is characteristic of the family irrespective of space and time. The dynamic character of family structures, - including members’ status, their associated roles, functions and interpersonal relationships, - has an important impact on a host of other social institutional spheres, prospective economic fortunes, political decision-making and sustainable futures. Assuming that the ultimate goal of all societies is to enhance quality of life, the family constitutes a worthy unit of inquiry. Whether from a social or economic standpoint, the family is critical in stimulating the well being of a people. The family has been and will continue to be subjected to myriad social, economic, cultural, political and environmental forces that shape it. -

Anthropology of Race 1

Anthropology of Race 1 Knowing Race John Hartigan What do we know about race today? Is it surprising that, after a hun- dred years of debate and inquiry by anthropologists, not only does the answer remain uncertain but also the very question is so fraught? In part, this reflects the deep investments modern societies have made in the notion of race. We can hardly know it objectively when it constitutes a pervasive aspect of our identities and social landscapes, determining advantage and disadvantage in a thoroughgoing manner. Yet, know it we do. Perhaps mis- takenly, haphazardly, or too informally, but knowledge claims about race permeate everyday life in the United States. As well, what we understand or assume about race changes as our practices of knowledge production also change. Until recently, a consensus was held among social scientists—predi- cated, in part, upon findings by geneticists in the 1970s about the struc- ture of human genetic variability—that “race is socially constructed.” In the early 2000s, following the successful sequencing of the human genome, counter-claims challenging the social construction consensus were formu- lated by geneticists who sought to support the role of genes in explaining race.1 This volume arises out of the fracturing of that consensus and the attendant recognition that asserting a constructionist stance is no longer a tenable or sufficient response to the surge of knowledge claims about race. Anthropology of Race confronts the problem of knowing race and the challenge of formulating an effective rejoinder both to new arguments and sarpress.sarweb.org COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 3 John Hartigan data about race and to the intense desire to know something substantive about why and how it matters. -

The Hmong Culture: Kinship, Marriage & Family Systems

THE HMONG CULTURE: KINSHIP, MARRIAGE & FAMILY SYSTEMS By Teng Moua A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree With a Major in Marriage and Family Therapy Approved: 2 Semester Credits _________________________ Thesis Advisor The Graduate College University of Wisconsin-Stout May 2003 i The Graduate College University of Wisconsin-Stout Menomonie, Wisconsin 54751 ABSTRACT Moua__________________________Teng_____________________(NONE)________ (Writer) (Last Name) (First) (Initial) The Hmong Culture: Kinship, Marriage & Family Systems_____________________ (Title) Marriage & Family Therapy Dr. Charles Barnard May, 2003___51____ (Graduate Major) (Research Advisor) (Month/Year) (No. of Pages) American Psychological Association (APA) Publication Manual_________________ (Name of Style Manual Used In This Study) The purpose of this study is to describe the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family systems in the format of narrative from the writer’s experiences, a thorough review of the existing literature written about the Hmong culture in these three (3) categories, and two structural interviews of two Hmong families in the United States. This study only gives a general overview of the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family systems as they exist for the Hmong people in the United States currently. Therefore, it will not cover all the details and variations regarding the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family which still guide Hmong people around the world. Also, it will not cover the ii whole life course transitions such as childhood, adolescence, adulthood, late adulthood or the aging process or life core issues. This study is divided into two major parts: a review of literature and two interviews of the two selected Hmong families (one traditional & one contemporary) in the Minneapolis-St. -

Social Organization III

08Ch08_Miller.QXD 12/15/08 9:34 PM Page 198 PART Social Organization III 8 Kinship and Domestic Life Social Groups and Social 9 Stratification 10 Politics, Conflict, and Social Order 08Ch08_Miller.QXD 12/15/08 9:34 PM Page 199 FREDY PECCERELLI, A FORENSIC ANTHROPOLOGIST, risks his personal security working for victims of political violence in his homeland. Peccerelli is founder and executive director of the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Founda- tion (Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala or FAFG), a group that focuses on the recovery and identifica- tion of some of the 200 000 people, mostly indigenous Maya of the mountainous regions, that Guatemalan military forces killed or “disappeared” during the brutal civil war that occurred between the mid-1960s and the mid-1990s. Peccerelli was born in Guatemala. His family immigrated to the United States when his father, a lawyer, was threatened by death squads. He grew up in New York and attended Brooklyn College in the 1990s. But he felt a need to reconnect with his heritage and began to study anthropology as a vehicle that would allow him to serve his country. The FAFG scientists excavate clandestine mass graves, exhume the bodies, and identify them through several means, such as matching dental and/or medical records. Anthropologists In studying skeletons, they try to determine the person’s age, gender, stature, ancestry, and lifestyle. DNA studies at are few because of the expense. The scientists also collect Work information from relatives of the victims and from eye- witnesses of the massacres. Since 1992, the FAFG team has discovered and exhumed approximately 200 mass grave sites in villages, fields, and churches. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

Formal Analysis of Kinship Terminologies and Its Relationship to What Constitutes Kinship (Complete Text)

MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 1 NO. 1 PAGE 1 OF 46 NOVEMBER 2000 FORMAL ANALYSIS OF KINSHIP TERMINOLOGIES AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO WHAT CONSTITUTES KINSHIP (COMPLETE TEXT) 1 DWIGHT W. READ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90035 [email protected] Abstract The goal of this paper is to relate formal analysis of kinship terminologies to a better understanding of who, culturally, are defined as our kin. Part I of the paper begins with a brief discussion as to why neither of the two claims: (1) kinship terminologies primarily have to do with social categories and (2) kinship terminologies are based on classification of genealogically specified relationships traced through genitor and genetrix, is adequate as a basis for a formal analysis of a kinship terminology. The social category argument is insufficient as it does not account for the logic uncovered through the formalism of rewrite rule analysis regarding the distribution of kin types over kin terms when kin terms are mapped onto a genealogical grid. Any formal account must be able to account at least for the results obtained through rewrite rule analysis. Though rewrite rule analysis has made the logic of kinship terminologies more evident, the second claim must also be rejected for both theoretical and empirical reasons. Empirically, ethnographic evidence does not provide a consistent view of how genitors and genetrixes should be defined and even the existence of culturally recognized genitors is debatable for some groups. In addition, kinship relations for many groups are reckoned through a kind of kin term calculus independent of genealogical connections. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

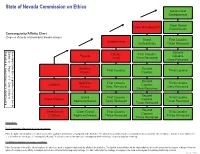

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

What's in a Name? Examining the Creation and Use of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Labels

Issues in Religion and Psychotherapy Volume 37 Number 1 Article 8 2015 What's in a Name? Examining the Creation and Use of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Labels Loren B. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/irp Recommended Citation Brown, Loren B. (2015) "What's in a Name? Examining the Creation and Use of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Labels," Issues in Religion and Psychotherapy: Vol. 37 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/irp/vol37/iss1/8 This Article or Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Issues in Religion and Psychotherapy by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Brown What’s in a Name Brown What’s in a Name? Examining the Creation and Use of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Labels Loren B. Brown, PhD Brigham Young University hat’s in a name?” Juliet famously asks. “That 2009; Sell, 1997). Attempts to be inclusive can lead to “Wwhich we call a rose / By any other name cumbersome lists (Zimmer et al., 2014), and attempts would smell as sweet” (Shakespeare, 1599/1914, to be efficient can lead to reductionist language which 2.2.47-48). Juliet suggests that the flower’s name leaves some individuals feeling misunderstood, ex- could easily be changed without altering our expe- cluded, marginalized, or invisible (Petchesky, 2009). rience of the flower’s scent. She extends this logic to Discussing this topic can lead to related conversa- her label as a Capulet and Romeo’s as a Montague, ar- tions about equality, gender roles, marriage, religious guing that since a name is not intrinsically connected freedom, historical oppression, and politics—subjects to one’s physical parts or personality, they should not on which there is no shortage of firm convictions and allow their surnames to get in the way of their love strong emotions.