“The Flood.” by Hannah Dübgen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structure and Meaning in Lamentations Homer Heater Liberty University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate Faculty Publications and Presentations School 1992 Structure and Meaning in Lamentations Homer Heater Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Heater, Homer, "Structure and Meaning in Lamentations" (1992). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 283. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/283 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate School at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Structure and Meaning in Lamentations Homer Heater, Jr. Professor of Bible Exposition Dallas Theological Seminary, Dallas, Texas Lamentations is perhaps the best example in the Bible of a com bination of divine inspiration and human artistic ability. The depth of pathos as the writer probed the suffering of Zion and his own suf fering is unprecedented. Each chapter is an entity in itself, a com plete poem.1 The most obvious literary device utilized by the poet is the acrostic; that is, poems are built around the letters of the alpha bet. -

Samuel D Giere Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository , 80@ 2647;=0 91 /,B 980 * ,8 48>0<>0A>?,6 34=>9<B 91 2080=4= %"%!( 48 30-<0@ ,8/ 2<005 >0A>= ?; >9 &$$ .0 =CNUGM /" 2KGRG , >JGSKS =UDNKTTGF HPR TJG /GIRGG PH ;J/ CT TJG ?OKVGRSKTY PH =T" ,OFRGWS &$$) 1UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO <GSGCREJ+=T,OFRGWS*1UMM>GXT CT* JTTQ*##RGSGCREJ!RGQPSKTPRY"ST!COFRGWS"CE"UL# ;MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN* JTTQ*##JFM"JCOFMG"OGT#%$$&'#%(( >JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT >JKS KTGN KS MKEGOSGF UOFGR C .RGCTKVG .PNNPOS 6KEGOSG A NEW GLIMPSE OF DAY ONE: AN INTERTEXTUAL HISTORY OF GENESIS 1.1-5 IN HEBREW AND GREEK TEXTS UP TO 200 CE BY SAMUEL D. GIERE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SUBMITTED 22 MAY 2006 ST MARY’S COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS ABSTRACT ABSTRACT This thesis is an unconventional history of the interpretation of Day One, Genesis 1.1-5, in Hebrew and Greek texts up to c. 200 CE. Using the concept of ‘intertextuality’ as developed by Kristeva, Derrida, and others, the method for this historical exploration looks at the dynamic interteconnectedness of texts. The results reach beyond deliberate exegetical and eisegetical interpretations of Day One to include intertextual, and therefore not necessarily deliberate, connections between texts. The purpose of the study is to gain a glimpse into the textual possibilities available to the ancient reader / interpreter. Central to the method employed is the identification of the intertexts of Day One. -

Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 As a Stylistic Guide

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2008 Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide Jonathan Candler Kilgore University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Composition Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kilgore, Jonathan Candler, "Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide" (2008). Dissertations. 1129. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC GUIDE by Jonathan Candler Kilgore A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts August 2008 COPYRIGHT BY JONATHAN CANDLER KILGORE 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC -

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah's Flood and Plate Tectonics

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah’s Flood and Plate Tectonics by Steven Ball, Ph.D. September 2003 Dedication I dedicate this work to my friend and colleague Rodric White-Stevens, who delighted in discussing with me the geologic wonders of the Earth and their relevance to Biblical faith. Cover picture courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, copyright free 1 Introduction It seems that no subject stirs the passions of those intending to defend biblical truth more than Noah’s Flood. It is perhaps the one biblical account that appears to conflict with modern science more than any other. Many aspiring Christian apologists have chosen to use this account as a litmus test of whether one accepts the Bible or modern science as true. Before we examine this together, let me clarify that I accept the account of Noah’s Flood as completely true, just as I do the entirety of the Bible. The Bible demonstrates itself to be reliable and remarkably consistent, having numerous interesting participants in various stories through which is interwoven a continuous theme of God’s plan for man’s redemption. Noah’s Flood is one of those stories, revealing to us both God’s judgment of sin and God’s over-riding grace and mercy. It remains a timeless account, for it has much to teach us about a God who never changes. It is one of the most popular Bible stories for children, and the truth be known, for us adults as well. It is rather unfortunate that many dismiss the account as mythical, simply because it seems to be at odds with a scientific view of the earth. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Virtual Edition in Honor of the 74Th Festival

ARA GUZELIMIAN artistic director 0611-142020* Save-the-Dates 75th Festival June 10-13, 2021 JOHN ADAMS music director “Ojai, 76th Festival June 9-12, 2022 a Musical AMOC music director Virtual Edition th Utopia. – New York Times *in honor of the 74 Festival OjaiFestival.org 805 646 2053 @ojaifestivals Welcome to the To mark the 74th Festival and honor its spirit, we bring to you this keepsake program book as our thanks for your steadfast support, a gift from the Ojai Music Festival Board of Directors. Contents Thursday, June 11 PAGE PAGE 2 Message from the Chairman 8 Concert 4 Virtual Festival Schedule 5 Matthias Pintscher, Music Director Bio Friday, June 12 Music Director Roster PAGE 12 Ojai Dawns 6 The Art of Transitions by Thomas May 16 Concert 47 Festival: Future Forward by Ara Guzelimian 20 Concert 48 2019-20 Annual Giving Contributors 51 BRAVO Education & Community Programs Saturday, June 13 52 Staff & Production PAGE 24 Ojai Dawns 28 Concert 32 Concert Sunday, June 14 PAGE 36 Concert 40 Concert 44 Concert for Ojai Cover art: Mimi Archie 74 TH OJAI MUSIC FESTIVAL | VIRTUAL EDITION PROGRAM 2020 | 1 A Message from the Chairman of the Board VISION STATEMENT Transcendent and immersive musical experiences that spark joy, challenge the mind, and ignite the spirit. Welcome to the 74th Ojai Music Festival, virtual edition. Never could we daily playlists that highlight the 2020 repertoire. Our hope is, in this very modest way, to honor the spirit of the 74th have predicted how altered this moment would be for each and every MISSION STATEMENT Ojai Music Festival, to pay tribute to those who imagined what might have been, and to thank you for being unwavering one of us. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

Toward a Theory of Formal Function in Stravinsky’S Neoclassical Keyboard Works

Toward a Theory of Formal Function in Stravinsky’s Neoclassical Keyboard Works Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Mueller, Peter M. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 03:29:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/626657 TOWARD A THEORY OF FORMAL FUNCTION IN STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICAL KEYBOARD WORKS by Peter M. Mueller __________________________ Copyright © Peter M. Mueller 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Valse Triste, Op. 44, No. 1

Much of the Sibelius Violin Concerto’s beauty comes from its eccentricity — while it has elements of a traditional Romantic concerto, Sibelius constantly asks the musicians to play in quirky, counterintuitive ways, and often pits the soloist and orchestra against each other. BOB ANEMONE, NCS VIOLIN Valse triste, Op. 44, No. 1 JEAN SIBELIUS BORN December 8, 1865, in Hämeenlinna, Finland; died September 20, 1957, in Järvenpää, Finland PREMIERE Composed 1903; first performance December 2, 1903, in Helsinki, conducted by the composer OVERVIEW Though Sibelius is universally recognized as the Finnish master of the symphony, tone poem, and concerto, he also produced a large amount of music in the more intimate forms, including the scores for 11 plays — the music to accompany a 1926 production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest was his last orchestral work. Early in 1903, Sibelius composed the music to underscore six scenes of a play by his brother-in-law, Arvid Järnefelt, titled Kuolema (“Death”). Among the music was a piece accompanying the scene in which Paavali, the central character, is seen at the bedside of his dying mother. She tells him that she has dreamed of attending a ball. Paavali falls asleep, and Death enters to claim his victim. The mother mistakes Death for her deceased husband and dances away with him. Paavali awakes to find her dead. Sibelius gave little importance to this slight work, telling a biographer that “with all retouching [it] was finished in a week.” Two years later he arranged the music for solo piano and for chamber orchestra as Valse triste (“Sad Waltz”), and sold it outright to his publisher, Fazer & Westerlund, for a tiny fee. -

5 Noah and the Flood

5 Noah and the Flood Read Genesis 6–9 Go into the ark, you and all your household, for I have seen that you alone are righteous. Genesis 7:ı he story of Noah is told to illustrate how deeply the human Tfamily has fallen into sinfulness. Sin is now so universal that a troubled God decides to complete the work of destruction that the human family has begun (Genesis 6:13). However, God sees that Noah is a good man and decides that humanity will survive through Noah’s family. God tells Noah to build an ark, which God will use to save Noah’s family and members of the animal kingdom. God is pained by and disappointed in humankind, but in his mercy he will save the human family through Noah. Noah builds the ark and, following God’s instructions, loads himself, his family, and the animals into it. God closes the door of the ark, showing his care for all inside and for the future human family. The flood comes, joining the waters of the sky with the waters on the earth. As the ark floats higher, everything beneath 11 12 • Noah and the Flood it drowns. For forty days and nights it rains. It is another 150 days before the water recedes. Then God remembers Noah. In his remembering, God begins the process of re-creation: “And God made a wind blow over the earth, and the waters subsided” (Genesis 8:1). Noah sends out birds to see if it is safe to disembark. He first sends a raven, then a dove. -

CHAN 9408 Cover.Qxd 26/3/08 11:34 Am Page 1

CHAN 9408 cover.qxd 26/3/08 11:34 am Page 1 Chan 9408 CHANDOS Stravinsky The Rite of Spring Requiem Canticles + Canticum Sacrum Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi CHAN 9408 BOOK.qxd 26/3/08 11:37 am Page 2 Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The Rite of Spring 32:42 PART I – Adoration of the Earth 1 Introduction – 3:13 2 The Augurs of Spring – Dances of the Young Girls – 3:46 3 Ritual of Abduction – 1:20 4 Spring Rounds – 3:31 5 Ritual of the River Tribes – 1:51 6 Procession of the Sage – 0:43 7 The Sage – 0:23 8 Dance of the Earth 1:16 PART II – The Sacrifice 9 Introduction – 3:57 10 Mystic Circles of the Young Girls – 3:11 11 Igor Stravinsky Glorification of the Chosen One – 1:26 12 0:49 AKG London Evocation of the Ancestors – 13 Ritual Action of the Ancestors – 3:06 14 Sacrificial Dance (The Chosen One) 4:09 Raynal Malsam bassoon solo 3 CHAN 9408 BOOK.qxd 26/3/08 11:37 am Page 4 Canticum Sacrum 16:40 Chorale Variations 10:40 15 Dedicatio 0:40 on the Christmas Carol ‘Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich 16 III Euntes in mundum 1:59 her’ (J. S. Bach) 17 III Surge, aquilo 2:25 32 Chorale 0:48 III Ad Tres Virtutes Hortationes 0:41 33 Variation I In canone all’Ottava 1:13 18 Caritas – 2:12 34 Variation II Alio modo in canone alla Quinta 1:14 19 Spes – 1:47 35 Variation III In canone alla Settima 1:51 20 Fides 2:46 36 Variation IV In canone all’Ottava per augmentationem 2:30 21 IV Brevis Motus Cantilenae 2:41 37 Variation V L’altra sorte del canone al rovescio 3:04 22 IV Illi autem profecti 1:58 TT 74:35 Requiem Canticles 14:01 Irène Friedli alto 23 Prelude 1:06 Frieder Lang tenor 24 Exaudi 1:34 Michel Brodard bass 25 Dies irae – 0:58 Chœur Pro Arte de Lausanne 26 Tuba mirum 1:07 Chœur de Chambre Romande 27 Interlude 2:31 André Charlet choir master 28 Rex tremendae 1:17 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande 29 Lacrimosa 1:55 Jean Piguet leader 30 Libera me 0:58 31 Postlude 2:18 Neeme Järvi 4 5 CHAN 9408 BOOK.qxd 26/3/08 11:37 am Page 6 process too. -

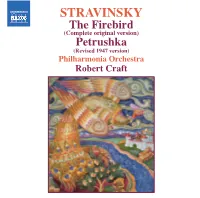

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise.