Hollywood Deals: Soft Contracts for Hard Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jason Constantine Promoted to President of Acquisitions and Coproductions for Lionsgate

JASON CONSTANTINE PROMOTED TO PRESIDENT OF ACQUISITIONS AND COPRODUCTIONS FOR LIONSGATE Move Reflects Continued Growth of Company's Motion Picture Operations SANTA MONICA, CA and VANCOUVER, BC (July 15, 2008) – Reflecting the continued growth of Lionsgate's motion picture business, eight-year Lionsgate veteran Jason Constantine has been promoted to President of Acquisitions and Coproductions for the Company's Motion Picture Group, it was announced today by Lionsgate co-Chief Operating Officer and Motion Picture Group President Joe Drake, to whom he reports. Lionsgate (NYSE: LGF) is the leading next generation filmed entertainment studio. Constantine will continue to oversee the tracking and acquisition of all theatrical films for Lionsgate, play an instrumental role in the creative oversight of prebuy projects in development, production and postproduction, and manage the day-to-day operations of Lionsgate's acquisition team. Constantine has played a key role in the acquisition of such Lionsgate box office hits and critical successes as the Saw franchise, which has grossed more than $500 million at the box office worldwide on its way to becoming the most popular horror franchise in history, Academy Award (R)-winning Best Picture CRASH, LORD OF WAR, GIRL WITH A PEARL EARRING, OPEN WATER, AWAY FROM HER and THE DESCENT. Recent acquisitions for the Company's upcoming motion picture slate include CONAN THE BARBARIAN, a potential action franchise slated for 2009 release, the action thriller BANGKOK DANGEROUS, starring Nicolas Cage as a hitman with a score to settle, TRANSPORTER 3, the next installment in the popular action franchise starring Jason Statham, and the romantic comedy CHILLED IN MIAMI, starring Renee Zellweger and Harry Connick, Jr. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Compare Results

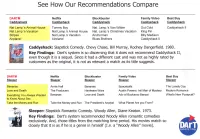

See How Our Recommendations Compare DARTM BestCaddvshackCaddyshackBuy AnchormanCaddvshackNat.BlockbusterBluesTommyNatCaddvshackAirplane!NetflixII Lamp.'sLamp.'sLamp.CaddyshackOutFamilyCaddvshackKingBillyBrothersBoyColdMadisonPin'sVanChristmasVideoAnimalVacationWilderII HouseVacation CaddvshackNat Lamp.'s VacationAirplane!Stripes Nat Lamp.'s Animal House Caddyshack: Slapstick Comedy. Chevy Chase, Bill Murray, Rodney Dangerfield. 1980. Key Findings: Dart's system is so discerning that it does not recommend Caddyshack II, even though it is a sequel. Since it had a different cast and was not as highly rated by customers as the original, it is not as relevant a match as its title suggests. DARTM AustinAdvSpaceballsSleeperFamilyWhatBlockbusterTheLoveHardwareBananasofPresident'sandPlanetPowers:BuckarooAnnieVideoTheSleeperTakeNetflixBananasDeathWarsWhat'sTheBestSleeperModernProducersAretheHallLonelyIntiBuyAnalystyouMoneyBanzaiNewManRomanceFrom?GuyPussycat?ofandMysteryRun SleepertoLoveKnowandAboutDeathSex Take the Money and Run EverythingBananas You Always Wanted Sleeper: Slapstick Romantic Comedy. Woody Allen, Diane Keaton. 1973. Key Findings: Dart's system recommended Woody Allen romantic comedies exclusively. And, chose titles from the matching time period. His movies match so closely that it is as if he is a genre in himself (I.e. a "Woody Allen" movie). DARTM WhereFamilyTearsRamboBestRamboTheofEaglesBeastVideoBuyIIItheTheCobraCommandoRockyOnMissingNetflixBlockbusterRamboRambo:IronIIISunDeadlyDogsEagleDareIVIIIinFirstofActionGroundWarBlood -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Dvds, Music Are Rent-Free at APL by KIMBERLY COON Couldn’T find Anyone to Borrow find Something to Suit Their Way Said

Page 4 ANDERSONIAN / Entertainment April 19, 2006 DVDs, music are rent-free at APL BY KIMBERLY COON couldn’t find anyone to borrow find something to suit their way said. ing free from the library is that ANDERSONIAN STAFF it from. tastes. It’s free for everyone, and cardholders 18 and older can Their solution? The Ander- From TV favorites like AU students need only to bring check out up 10 DVDs and hen sophomore Maggie son Public Library. Friends, Will & Grace, Alias and a copy of their current class 10 videos on their card at one WGrumieaux and junior “The library is a great place even 90210 to recently popular schedule and current photo time. Katie Briski discovered their to get DVDs and videos,” Bris- movies like “Fever Pitch,” “Le- identification to sign up for a For more information, love for the WB’s popular series ki said. She discovered the place gally Blonde” and “Hitch,” the card. check out the library’s web site Gilmore Girls, they couldn’t stop last summer. “They really have a library boasts variety. Check-out times range from at http://www.and.lib.in.us/. watching the show on DVD. lot more than people think.” Classics like “Pretty Wom- seven days for DVDs and vid- “It’s just one of those In addition to books and an” and Marilyn Monroe’s fa- eos to 14 days for new books, shows,” Grumieaux said. “It’s other resources, the library of- mous “Seven Year Itch” are also audiobooks and CDs, but all fun to watch, and I feel like I fers free rental of videos, CDs available, and if you’re willing items can easily be renewed. -

275. – Part One

275. – PART ONE 275. Clifford (1994) Okay, here’s the deal: I don’t know you, you don’t know me, but if you are anywhere near a television right now I need you to stop whatever it is that you’re doing and go watch “Clifford” on HBO Max. This is another film that has a 10% score on Rotten Tomatoes which just leads me to believe that all of the critics who were popular in the nineties didn’t have a single shred of humor in any of their non-existent funny bones. I loved this movie when I was seven, and I love it even more when I’m thirty-three. It’s genius. Martin Short (who at the time was forty-four) plays a ten-year-old hyperactive nightmare child from hell. I mean it, this kid might actually be the devil. He is straight up evil, conniving, manipulative and all-told probably causes no less than ten million dollars-worth of property damage. And, again, the plot is so simple – he just wants to go to Dinosaur World. There are so many comedy films with such complicated plots and motivations for their characters, but the simplistic genius of “Clifford” is just this – all this kid wants on the entire planet is to go to Dinosaur World. That’s it. The movie starts with him and his parents on an plane to Hawaii for a business trip, and Clifford knows that Dinosaur Land is in Los Angeles, therefore he causes so much of a ruckus that the plane has to make an emergency landing. -

Seawood Village Movies

Seawood Village Movies No. Film Name 1155 DVD 9 1184 DVD 21 1015 DVD 300 348 DVD 1408 172 DVD 2012 704 DVD 10 Years 1175 DVD 10,000 BC 1119 DVD 101 Dalmations 1117 DVD 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 DVD 12 Rounds 843 DVD 127 Hours 446 DVD 13 Going on 30 474 DVD 17 Again 523 DVD 2 Days In New York 208 DVD 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 DVD 21 Jump Street 1145 DVD 27 Dresses 1079 DVD 3:10 to Yuma 1124 DVD 30 Days of Night 204 DVD 40 Year Old Virgin 1101 DVD 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 DVD 50 First Dates 117 DVD 6 Souls 1205 DVD 88 Minutes 177 DVD A Beautiful Mind 643 DVD A Bug's Life 255 DVD A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 DVD A Christmas Carol 581 DVD A Christmas Story 506 DVD A Good Day to Die Hard 212 DVD A Knights Tale 848 DVD A League of Their Own 856 DVD A Little Bit of Heaven 1053 DVD A Mighty Heart 961 DVD A Thousand Words 1139 DVD A Turtle's Tale: Sammy's Adventure 376 DVD Abduction 540 DVD About Schmidt 1108 DVD Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter 1160 DVD Across the Universe 812 DVD Act of Valor 819 DVD Adams Family & Adams Family Values 724 DVD Admission 519 DVD Adventureland 83 DVD Adventures in Zambezia 745 DVD Aeon Flux 585 DVD Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 DVD Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 496 DVD Alex & Emma 79 DVD Alex Cross 947 DVD Ali 1004 DVD Alice in Wonderland 525 DVD Alice in Wonderland - Animated 838 DVD Aliens in the Attic 1034 DVD All About Steve 1103 DVD Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 785 DVD Alpha and Omega 970 DVD Alpha Dog 522 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked -

GREG TILLMAN Editor

GREG TILLMAN Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. THE NIGHT STALKER (limited series) Tiller Russell Netflix Prod: Eli Holzman, Aaron Saidman, Tim Walsh, Cameron Jewell BROCKMIRE (season 3) Various IFC / Funny or Die Prod: Joel Church-Cooper, Tim Kirkby, Joe Farrell, Elizabeth Baquet, Mike Farah GHOSTED (season 1) Various Fox / 3 Arts Entertainment Prod: Kevin Etten, Tom Gornican, Oliver Obst, Mark Schulman, Adam Scott FLAKED (seasons 1-2) Various Netflix Prod: Mitchell Hurwitz, Peter Principato, Ben Silverman, Wally Pfister DOGS OF WAR (series) Various A + E / Custom Productions OUTLAW EMPIRES (series) Various Discovery / Creator: Kurt Sutter LAGUNA BEACH (series) Various MTV SMALL TOWN SECRETS (series) Various CMT / Planet Grande FEARLESS: DAVE MIRRA BMX (series) Various Outdoor Life Feature Films / Documentaries PROJECT STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. UNTITLED SHANIA TWAIN DOCUMENTARY Fran Strine Tiny Terror Productions OPERATION ODESSA (documentary) Tiller Russell Showtime Official Selection: SXSW Film Festival + Miami Film Festival Prod: Eli Holzman, Aaron Saidman, Sheldon Yellen SHE’S FUNNY THAT WAY* Peter Bogdanovich Lionsgate Premiere / Lagniappe Films THAT AWKWARD MOMENT Tom Gormican Focus Features / Treehouse Pictures ELSEWHERE Nathan Hope IM Global / Lost Toys THE ZODIAC Alex Bulkley Myriad Films / ShadowMachine KISSING JESSICA STEIN Charles Herman-Wurmfeld Fox Searchlight Audience Award - Best Feature: IFP West Los Angeles Film Festival Prod: Doug Liman, Mark Pincus, FedEx Audience Award: Miami Film Festival Brad -

Uncertainty in the Movie Industry: Does Star Power Reduce the Terror of the Box O�Ce?

Uncertainty in the Movie Industry: Does Star Power Reduce the Terror of the Box O±ce?¤ Arthur De Vany Department of Economics Institute for Mathematical Behavioral Sciences University of California Irvine, CA 92697 USA W. David Walls School of Economics and Finance The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong Abstract Everyone knows that the movie business is risky. But how risky is it? Do strategies exist that reduce risk? We investigate these ques- tions using a sample of over 2000 motion pictures. We discover that the movies are very risky indeed. Box-o±ce revenue dynamics are a Le'vy stable process and are asymptotically Pareto-distributed with in¯nite variance. The mean is dominated by rare blockbuster movies that are located in the far right tail. There is no typical movie be- cause box o±ce revenue outcomes do not converge to an average, they diverge over all scales. Movies with stars in them have higher revenue ¤This paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Economic Associa- tion, New York, January 1999. Walls received support from the Committee on Research and Conference Grants of the University of Hong Kong. De Vany received support from the Private Enterprise Research Center of Texas A&M University. 1 expectations, but in¯nite variance. Only 19 stars have a positive cor- relation with the probability that a movie will be a hit. No star is \bankable" if bankers want sure things; they all carry signi¯cant risk. The highest grossing movies enjoy long runs and their total revenue is only weakly associated with their opening revenue. -

Executive Producer

‘CHRISTMAS UNDER WRAPS’ PRODUCTION BIOS JEFFREY SCHENCK (Executive Producer) – Jeffrey Schenck is an independent film and television producer who has his own production company, ARO ENTERTAINMENT along with owning and operating HYBRID with his producing partner, Barry Barnholtz. Schenck's professional roots are also strongly intertwined with his personal history. His great uncles, Joe and Nick Schenck, were involved in the origins of the motion picture business, including the founding and management of MGM and Fox. Prior to starting ARO and HYBRID, Schenck was the president of Regent Studios and over the past thirteen years with the company, had been involved with over fifty movies from conception to completion. Schenck oversaw the entire production arm of Regent, which services content for all of the company's distribution platforms as well as other television networks. He was responsible for the studio's operations including development, financing and all aspects of budgeting and physical production. Schenck also directed the domestic distribution relationships including television and home entertainment. Under Schenck's leadership, Regent became one of the most prolific producers of television/DVD content in the entertainment industry. Notable films he produced include several highly rated television films such as “Doomsday Rock,” “Catch Me If You Can” (Family Channel), “Chupacabra,” “Ice Spiders” (Syfy Channel),”I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus” (Pax), “Eve’s Christmas,” “Home for the Holidays” (Lifetime), “Chasing Chrsitmas” and “Christmas -

Sundayiournal

STANDING STRONG FOR 1,459 DAYS — THE FIGHT'S NOT OVER YET JULY 11-17, 1999 THE DETROIT VOL. 4 NO. 34 75 CENTS S u n d a yIo u r n a l PUBLISHED BY LOCKED-OUT DETROIT NEWSPAPER WORKERS ©TDSJ JIM WEST/Special to the Journal Nicholle Murphy’s support for her grandmother, Teamster Meka Murphy, has been unflagging. Marching fourward Come Tuesday, it will be four yearsstrong and determined. In this editionOwens’ editorial points out the facthave shown up. We hope that we will since the day in July of 1995 that ofour the Sunday Journal, co-editor Susanthat the workers are in this strugglehave contracts before we have to put Detroit newspaper unions were forcedWatson muses on the times of happiuntil the end and we are not goingtogether any another anniversary edition. to go on strike. Although the companess and joy, in her Strike Diarywhere. on On Pages 19-22 we show offBut four years or 40, with your help, nies tried mightily, they never Pagedid 3. Starting on Page 4, we putmembers the in our annual Family Albumsolidarity and support, we will be here, break us. Four years after pickingevents up of the struggle on the record.and also give you a glimpse of somestanding of strong. our first picket signs, we remainOn Page 10, locked-out worker Keiththe far-flung places where lawn signs— Sunday Journal staff PAGE 10 JULY 11 1999 Co-editors:Susan Watson, Jim McFarlin --------------------- Managing Editor: Emily Everett General Manager: Tom Schram Published by Detroit Sunday Journal Inc.