Mass Spectrometryspectrometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theoretical Calculations for Electron Impact Ionization of Atoms and Molecules

Scholars' Mine Doctoral Dissertations Student Theses and Dissertations Fall 2017 Theoretical calculations for electron impact ionization of atoms and molecules Sadek Mohamed Fituri Amami Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertations Part of the Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics Commons Department: Physics Recommended Citation Amami, Sadek Mohamed Fituri, "Theoretical calculations for electron impact ionization of atoms and molecules" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 2617. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertations/2617 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEORETICAL CALCULATIONS FOR ELECTRON IMPACT IONIZATION OF ATOMS AND MOLECULES by SADEK MOHAMED FITURI AMAMI A DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the MISSOURI UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in PHYSICS 2017 Approved by Don H. Madison, Advisor Jerry L. Peacher Michael Schulz Daniel Fischer Gregory Gelles Copyright 2017 SADEK MOHAMED FITURI AMAMI All Rights Reserved iii PUBLICATION DISSERTATION OPTION This dissertation consists of the following ten articles which have been published as follows: Paper I: Pages 31-54 have been published by Phys Rev A.91.032707 (March 2015). Paper II: Pages 55-78 have been published by Phys Rev A.90.012704 (July 2014). Paper III: Pages 79-93 have been published by J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 49 185202 (September 2016). -

Electron Ionization

Chapter 6 Chapter 6 Electron Ionization I. Introduction ......................................................................................................317 II. Ionization Process............................................................................................317 III. Strategy for Data Interpretation......................................................................321 1. Assumptions 2. The Ionization Process IV. Types of Fragmentation Pathways.................................................................328 1. Sigma-Bond Cleavage 2. Homolytic or Radical-Site-Driven Cleavage 3. Heterolytic or Charge-Site-Driven Cleavage 4. Rearrangements A. Hydrogen-Shift Rearrangements B. Hydride-Shift Rearrangements V. Representative Fragmentations (Spectra) of Classes of Compounds.......... 344 1. Hydrocarbons A. Saturated Hydrocarbons 1) Straight-Chain Hydrocarbons 2) Branched Hydrocarbons 3) Cyclic Hydrocarbons B. Unsaturated C. Aromatic 2. Alkyl Halides 3. Oxygen-Containing Compounds A. Aliphatic Alcohols B. Aliphatic Ethers C. Aromatic Alcohols D. Cyclic Ethers E. Ketones and Aldehydes F. Aliphatic Acids and Esters G. Aromatic Acids and Esters 4. Nitrogen-Containing Compounds A. Aliphatic Amines B. Aromatic Compounds Containing Atoms of Nitrogen C. Heterocyclic Nitrogen-Containing Compounds D. Nitro Compounds E. Concluding Remarks on the Mass Spectra of Nitrogen-Containing Compounds 5. Multiple Heteroatoms or Heteroatoms and a Double Bond 6. Trimethylsilyl Derivative 7. Determining the Location of Double Bonds VI. Library -

Mass Spectrometry (Technically Not Spectroscopy)

Mass Spectrometry (technically not Spectroscopy) So far, In mass spec, on y Populati Intensit Excitation Energy “mass” (or mass/charge ratio) Spectroscopy is about Mass spectrometry interaction of energy with matter. measures population of ions X-axis is real. with particular mass. General Characteristics of Mass Spectrometry 2. Ionization Different variants of 1-4 -e- available commercially. 4. Ion detection 1. Introduction of sample to gas phase (sometimes w/ separation) 3. Selection of one ion mass (Selection nearly always based on different flight of ion though vacuum.) General Components of a Mass Spectrometer Lots of choices, which can be mixed and matched. direct injection The Mass Spectrum fragment “daughter” ions M+ “parent” mass Sample Introduction: Direc t Inser tion Prob e If sample is a liquid, sample can also be injected directly into ionization region. If sample isn’t pure, get multiple parents (that can’t be distinguished from fragments). Capillary Column Introduction Continous source of molecules to spectrometer. detector column (including GC, LC, chiral, size exclusion) • Signal intensity depends on both amount of molecule and ionization efficiency • To use quantitatively, must calibrate peaks with respect eltilution time ttlitotal ion curren t to quantity eluted (TIC) over time Capillary Column Introduction Easy to interface with gas or liquid chromatography. TIC trace elution time time averaged time averaged mass spectrum mass spectrum Methods of Ionization: Electron Ionization (EI) 1 - + - 1 M + e (kV energy) M + 2e Fragmentation in Electron Ionization daughter ion (observed in spectrum) neutral fragment (not observed) excited parent at electron at electron energy of energy of 15 eV 70 e V Lower electron energy yields less fragmentation, but also less signal. -

An Organic Chemist's Guide to Electrospray Mass Spectrometric

molecules Review An Organic Chemist’s Guide to Electrospray Mass Spectrometric Structure Elucidation Arnold Steckel 1 and Gitta Schlosser 2,* 1 Hevesy György PhD School of Chemistry, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/A, 1117 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] 2 Department of Analytical Chemistry, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/A, 1117 Budapest, Hungary * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 January 2019; Accepted: 8 February 2019; Published: 10 February 2019 Abstract: Tandem mass spectrometry is an important tool for structure elucidation of natural and synthetic organic products. Fragmentation of odd electron ions (OE+) generated by electron ionization (EI) was extensively studied in the last few decades, however there are only a few systematic reviews available concerning the fragmentation of even-electron ions (EE+/EE−) produced by the currently most common ionization techniques, electrospray ionization (ESI) and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI). This review summarizes the most important features of tandem mass spectra generated by collision-induced dissociation fragmentation and presents didactic examples for the unexperienced users. Keywords: tandem mass spectrometry; MS/MS fragmentation; collision-induced dissociation; CID; ESI; structure elucidation 1. Introduction Electron ionization (EI), a hard ionization technique, is the method of choice for analyses of small (<1000 Da), nonpolar, volatile compounds. As its name implies, the technique involves ionization by electrons with ~70 eV energy. This energy is high enough to yield very reproducible mass spectra with a large number of fragments. However, these spectra frequently lack the radical type molecular ions (M+) due to the high internal energy transferred to the precursors [1]. -

Methods of Ion Generation

Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 361−375 361 Methods of Ion Generation Marvin L. Vestal PE Biosystems, Framingham, Massachusetts 01701 Received May 24, 2000 Contents I. Introduction 361 II. Atomic Ions 362 A. Thermal Ionization 362 B. Spark Source 362 C. Plasma Sources 362 D. Glow Discharge 362 E. Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) 363 III. Molecular Ions from Volatile Samples. 364 A. Electron Ionization (EI) 364 B. Chemical Ionization (CI) 365 C. Photoionization (PI) 367 D. Field Ionization (FI) 367 IV. Molecular Ions from Nonvolatile Samples 367 Marvin L. Vestal received his B.S. and M.S. degrees, 1958 and 1960, A. Spray Techniques 367 respectively, in Engineering Sciences from Purdue Univesity, Layfayette, IN. In 1975 he received his Ph.D. degree in Chemical Physics from the B. Electrospray 367 University of Utah, Salt Lake City. From 1958 to 1960 he was a Scientist C. Desorption from Surfaces 369 at Johnston Laboratories, Inc., in Layfayette, IN. From 1960 to 1967 he D. High-Energy Particle Impact 369 became Senior Scientist at Johnston Laboratories, Inc., in Baltimore, MD. E. Low-Energy Particle Impact 370 From 1960 to 1962 he was a Graduate Student in the Department of Physics at John Hopkins University. From 1967 to 1970 he was Vice F. Low-Energy Impact with Liquid Surfaces 371 President at Scientific Research Instruments, Corp. in Baltimore, MD. From G. Flow FAB 371 1970 to 1975 he was a Graduate Student and Research Instructor at the H. Laser Ionization−MALDI 371 University of Utah, Salt Lake City. From 1976 to 1981 he became I. -

1 Introduction of Mass Spectrometry and Ambient Ionization Techniques

1 1 Introduction of Mass Spectrometry and Ambient Ionization Techniques Yiyang Dong, Jiahui Liu, and Tianyang Guo College of Life Science & Technology, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, No. 15 Beisanhuan East Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100029, China 1.1 Evolution of Analytical Chemistry and Its Challenges in the Twenty-First Century The Chemical Revolution began in the eighteenth century, with the work of French chemist Antoine Lavoisier (1743–1794) representing a fundamental watershed that separated the “modern chemistry” era from the “protochemistry” era (Figure 1.1). However, analytical chemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, is an ancient science and its metrological tools, basic applications, and analytical processes can be dated back to early recorded history [1]. In chronological spans covering ancient times, the middle ages, the era of the nineteenth century, and the three chemical revolutionary periods, analytical chemistry has successfully evolved from the verge of the nineteenth century to modern and contemporary times, characterized by its versatile traits and unprecedented challenges in the twenty-first century. Historically, analytical chemistry can be termed as the mother of chemistry, as the nature and the composition of materials are always needed to be iden- tified first for specific utilizations subsequently; therefore, the development of analytical chemistry has always been ahead of general chemistry [2]. During pre-Hellenistic times when chemistry did not exist as a science, various ana- lytical processes, for example, qualitative touchstone method and quantitative fire-assay or cupellation scheme have been in existence as routine quality control measures for the purpose of noble goods authentication and anti-counterfeiting practices. Because of the unavailability of archeological clues for origin tracing, the chemical balance and the weights, as stated in the earliest documents ever found, was supposed to have been used only by the Gods [3]. -

Electrification Ionization: Fundamentals and Applications

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 11-12-2019 Electrification Ionization: undamentalsF and Applications Bijay Kumar Banstola Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Analytical Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Banstola, Bijay Kumar, "Electrification Ionization: undamentalsF and Applications" (2019). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5103. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5103 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ELECTRIFICATION IONIZATION: FUNDAMENTALS AND APPLICATIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Chemistry by Bijay Kumar Banstola B. Sc., Northwestern State University of Louisiana, 2011 December 2019 This dissertation is dedicated to my parents: Tikaram and Shova Banstola my wife: Laxmi Kandel ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my advisor Professor Kermit K. Murray, for his continuous support and guidance throughout my Ph.D. program. Without his unwavering guidance and continuous help and encouragement, I could not have completed this program. I am also thankful to my committee members, Professor Isiah M. Warner, Professor Kenneth Lopata, and Professor Shengli Chen. I thank Dr. Fabrizio Donnarumma for his assistance and valuable insights to overcome the hurdles throughout my program. I appreciate Miss Connie David and Dr. -

Experimental Study on Electron Impact Double Ionization Dynamics for Atomic and Small Molecular Targets at Intermediate Incident Energy Chengjun Li

Experimental study on electron impact double ionization dynamics for atomic and small molecular targets at intermediate incident energy Chengjun Li To cite this version: Chengjun Li. Experimental study on electron impact double ionization dynamics for atomic and small molecular targets at intermediate incident energy. Other [cond-mat.other]. Université Paris Sud - Paris XI, 2013. English. NNT : 2013PA112055. tel-00867037 HAL Id: tel-00867037 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00867037 Submitted on 27 Sep 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE PARIS-SUD Ecole Doctorale Ondes et Matière Institut des Sciences Moléculaires d‟Orsay DISCIPLINE Physique THÈSE DE DOCTORAT soutenue le 25/04/2013 par Chengjun LI Experimental study on electron impact double ionization dynamics for atomic and small molecular targets at intermediate incident energy Directeur de thèse: Elena-Magdalena STAICU-CASAGRANDE MdC(HDR) (Université Paris Sud XI) Composition du jury : Président du jury : Christophe BLONDEL DR (Université Paris Sud XI) Rapporteurs -

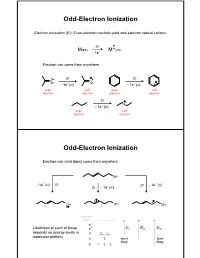

Odd-Electron Ionization

Odd-Electron Ionization Electron Ionization (EI): Even-electron neutrals yield odd-electron radical cations. EI + M(EE) M (OE) -1e- Electron can come from anywhere. EI EI O O -1e- (n) -1e- () even odd even odd electron electron electron electron EI -1e- () even odd electron electron Odd-Electron Ionization Electron can (and does) come from anywhere. OH - - -1e (n) EI EI -1e () EI - 1e- () OH OH OH vacuum level * Likelihood of each of these * IEn IE IE depedependsnds oonn eenergynergy levelslevels in n molecular orbitals: most least likely likely Odd-Electron Ionization Electron can (and does) come from anywhere. OH - - -1e (n) EI EI -1e () EI - 1e- () OH OH OH Naturally, cannot distinguish these in mass spectrometer (all have m/z = 100). But fraggpmentation patterns will be different. Even-Electron Ionization CI, MALDI and ESI: Even-electron neutrals yield even-electron cations. + + M(EE) + H MH (EE) Like EI, ion iza tion may occur a t mu ltip le p laces. H OO + H+ + H+ H + H + H H OO OO Again, instrument cannot distinguish. Fragmentation Mechanisms in EI-MS Electron Ionization: Fragmentation is always unimolecular. Two possible categories of fragmentation: parents daughters + + M (OE) A (EE) + B (OE) charge migration (radical and charge part ways) + + M (OE) A (OE) + B(EE) charge retention (neutral molecule is ejected) Important: Only daughter ions are detected by MS instrument. Released neutrals are only inferred. Alkane Fragmentation in EI-MS: EI (electron can come from any bond) or + + + + Fragmentation (one-electron bond can break either way) + + + CH 3 + CH3 15 43 57 71 + + + CH CH 3 + 3 71 43 29 15 Alkane Fragmentation in EI-MS dance n lative Abu e R m/z + + + CH3 + CH3 15 43 57 71 + + + CH CH 3 + 3 71 43 29 15 Alkane Fragmentation in EI-MS What governs which ions are predominant? 1. -

Infrared Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Infrared laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry: fundamental and applications Mark Little Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Little, Mark, "Infrared laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry: fundamental and applications" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2690. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2690 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. INFRARED LASER DESORPTION/IONIZATION MASS SPECTROMETRY: FUNDAMENTALS AND APPLICATIONS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Chemistry by Mark Little B.S., Wake Forest University, 1998 December 2006 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The popular quote, "L'enfer, c'est les autres" from an existential play by Jean-Paul Sartre is translated “Hell is other people”. I chose this quote because if it were not for all the “other people” in my life, I would be sitting on a beach right now sipping margaritas but I would not have my Ph.D. Therefore, I raise my salt covered glass to all my friends, family and colleagues for without their support this program of study would never been completed. -

Periodic Trends in Atomic Properties Why? Many Properties of Atoms Have a Repeating Pattern When Plotted with Respect to Atomic Number

Periodic Trends in Atomic Properties Why? Many properties of atoms have a repeating pattern when plotted with respect to atomic number. The similarities are due to the repeating pattern of electron configurations involving s, p, d, and f orbitals. The experimentally observed periodic trends in fact provide evidence for the orbital and shell structure of atoms and the meaningful arrangement of elements in the Periodic Table. Your ability to recognize the properties of the elements from their positions in the Periodic Table will prove useful in handling chemical compounds safely, developing new materials, finding new applications of known materials, or using chemistry in medical applications. Learning Objectives λ Develop relationships between position in the Periodic Table and electron configurations with atomic radius, ionization energy, and electron affinity. Success Criteria λ Use electron configurations to account for the relative sizes, ionization energies, and electron affinities of different atoms. λ Order elements by atomic radius, ionization energy, and electron affinity. Information Properties such as the size of an atom (atomic radius), the energy required to remove an electron from an atom (ionization energy), and the energy required to remove an electron from a negative atomic ion (electron affinity) can be understood in terms of the electron configuration of the atom and a competition between electron-nucleus attraction and electron-electron repulsion. An electron in an atom is attracted by the positively charged nucleus and repelled by the other electrons. Which one dominates depends on how effective the electrons are in getting close to each other or close to the nucleus. If the electron-nucleus attraction has a large effect, then the atom is small, has a high ionization energy, and large electron affinity. -

Internal Fragments Generated by Electron Ionization Dissociation En- Hances Protein Top-Down Mass Spectrometry Muhammad A

Internal fragments generated by electron ionization dissociation en- hances protein top-down mass spectrometry Muhammad A. Zenaidee,1 Carter Lantz,1 Taylor Perkins,1 Wonhyuek Jung,1 Rachel R. Ogorzalek Loo,2 Joseph A. Loo 1,2 1 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 2 Department of Biological Chemistry, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA ABSTRACT: Top-down proteomics by mass spectrometry (MS) involves the mass measurement of an intact protein followed by subsequent activation of the protein to generate product ions. Electron-based fragmentation methods like electron capture dissocia- tion (ECD) and electron transfer dissociation (ETD) are widely used for these types of analysis. Recently, electron ionization disso- ciation (EID), which utilizes higher energy electrons (> 20 eV) has been suggested to be more efficient for top-down protein frag- mentation compared to other electron-based dissociation methods. Here we demonstrate that the use of EID enhances protein frag- mentation and subsequent detection of protein fragments. Protein product ions can form by either single cleavage events, resulting in terminal fragments containing the C-terminus or N-terminus of the protein, or by multiple cleavage events to give rise to internal fragments that include neither the C-terminus nor N-terminus of the protein. Conventionally, internal fragments have been disre- garded as reliable assignments of these fragments were limited. Here, we demonstrate that internal fragments generated by EID can account for ~20-40% of the mass spectral signals detected by top-down EID-MS experiments. By including internal fragments, the extent of the protein sequence that can be explained from a single tandem mass spectrum increases from ~50% to ~99% for 29 kDa carbonic anhydrase II and 8.6 kDa ubiquitin.