Gender Differences in the Experience of Psychosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Televisionization: Enactments of TV Experiences in Novels from 1970 to 2010 Claudia Weber

Claudia Weber Claudia Televisionization Enactments of TV Experiences in Novels from 1970 to 2010 Claudia Weber Televisionization Claudia Weber pursued her doctoral studies both at Stock- holm University, Sweden and Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen, Germany. She is now employed at Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany where she works in higher education didactics. ISBN 978-91-7447-979-9 Department of English Doctoral Thesis in English at Stockholm University, Sweden 2014 Televisionization: Enactments of TV Experiences in Novels from 1970 to 2010 Claudia Weber Televisionization Enactments of TV Experiences in Novels from 1970 to 2010 Claudia Weber © Claudia Weber, Stockholm University 2014 ISBN 978-91-7447-979-9 Printed in Sweden by Stockholm University Press, Stockholm 2014 Distributor: Department of English Abstract TV’s conquest of the American household in the period from the 1940s to the 1960s went hand in hand with critical discussions that revolved around the disastrous impact of television consumption on the viewer. To this day, watching television is connected with anxieties about the trivialization and banalization of society. At the same time, however, people appreciate it both as a source of information and entertainment. Television is therefore ‘both…and:’ entertainment and anxiety; distraction and allurement; compan- ionship and intrusion. When the role and position of television in culture is ambiguous, personal relations with, attitudes towards, and experiences of television are equally ambivalent, sometimes even contradictory, but the public and academic discourses on television tend to be partial. They focus on the negative impact of television consumption on the viewer, thereby neglecting whatever positive experiences one might associate with it. -

'The Assault on Mount B' by Rod Fee 1/129

‘The Assault on Mount B’ by Rod Fee 1/129 Rod Fee ID:0826790 ‘The Assault on Mount B: understanding the role of story in self-delusion in our personal histories.’ A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2015 Faculty: Applied Humanities School: Languages and Social Sciences Primary Supervisor: Dr Paul Mountfort Secondary Supervisor: Dr Maria O’Connor ‘The Assault on Mount B’ by Rod Fee 2/129 ATTESTATION OF AUTHORSHIP I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person (except where explicitly defined in the acknowledgements), nor material which to a substantial extent has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institution of higher learning. R H Fee ‘The Assault on Mount B’ by Rod Fee 3/129 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge the assistance of: 1. My two supervisors Dr Paul Mountfort and Dr Maria O’Connor, and Associate Professor Mark Jackson mentor supervisor, all of AUT University ‘The Assault on Mount B’ by Rod Fee 4/129 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS 1. All intellectual property including copyright, is retained by the candidate in the content of the candidate’s thesis. For the removal of doubt, publication by the candidate of this or any derivative work does not change the intellectual property rights of the candidate in relation to the thesis. 2. I confirm that my thesis does not contain plagiarised material or material for which the copyright or other intellectual property belongs to a third party. -

Learning from Delusions

OPINION Brian Martin nce or twice a year, I receive a call or Learning email from some- O one claiming to be under intensive tar- geted surveillance by the govern- from Delusions ment. They contact me because there’s a lot of material on my website about whistleblowing, and some about surveillance. I know governments carry out massive sur- veillance operations, for example collecting all sorts of electronic With others, the delusion is more ers, it just doesn’t make sense: there communications. However, these obvious, for example when they say is no obvious reason for them to be callers believe they have been spe- that a television program contains a an ongoing target of personalized cially selected as surveillance tar- message specifically designed and surveillance and harassment. gets, and sometimes for electronic inserted to affect their minds. or chemical bombardment too. My friend Steve Wright used The Truman Show Delusion One caller said he had written to work for the Omega Founda- With this background, I noticed a a political novel — unpublished — tion in Britain, which studies the book entitled Suspicious Minds. On and therefore the government was technology of repression, includ- the book jacket is the teaser “The monitoring his calls and following ing technologies for surveillance Truman Show delusion and other his every movement. He was very and electronic assault. He told me strange beliefs.” convincing. I suggested that he the Foundation would regularly The Truman Show is the name obtain evidence of the surveillance, hear from people who believed they of a film presenting the fictional but he always had some excuse, so were being electronically harassed. -

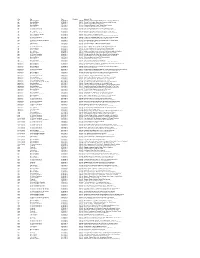

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 07/03/2013 0

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 07/03/2013 0:04:00 Doctors Recommend Baby Boomers Get Tested For Hepatitis C Age Morning Edition 07/05/2013 0:04:59 Seniors Flex Creative Muscles In Retirement Arts Colonies Age Tell Me More 07/08/2013 0:16:26 Winning Gold In Their Golden Years Age Morning Edition 07/11/2013 0:03:44 Chinatown 'Blessing Scams' Target Elderly Women Age Here & Now 07/18/2013 0:03:42 Cleveland Hosts National Senior Games Age All Things Considered 07/22/2013 0:07:20 Can Elderly Patients With Dementia Consent To Sex? Age All Things Considered 07/24/2013 0:05:37 Move Over Nursing Homes - There's Something Different Age Here & Now 07/25/2013 0:04:12 New Alzheimer's Research Could Lead To Treatments Age All Things Considered 07/26/2013 0:03:54 Age Hasn't Stopped This Man From Swimming And Winning Age Weekend Edition Sunday 07/28/2013 0:03:42 Athletic Glory At An Advanced Age Age Morning Edition 07/31/2013 0:03:55 Pickleball, Anyone? Senior Athletes Play New Games And Old Age All Things Considered 07/31/2013 0:04:45 For One Seniors Basketball Team, The Game Never Gets Old Age Here & Now 08/01/2013 0:16:27 Nursing Home Encourages Residents To Have Sex Age All Things Considered (Weekend) 08/03/2013 0:03:16 Worms' Bright Blue Death Could Shed Light On Human Aging Age Tell Me More 08/07/2013 0:01:35 Never Too Old To Take Gold Age Tell Me More 08/12/2013 0:19:38 Are We Ready For A Massive Aging Population? Age Morning Edition 08/20/2013 0:04:43 Older Farmers Seem To Be In No Hurry At All Age All Things Considered 08/23/2013 0:04:12 Summer Nights: Senior Softball In Huntington Beach, Calif. -

A CULTURAL HISTORY of MADNESS - Bloomsbury

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF MADNESS - Bloomsbury GENERAL EDITORS Jonathan Sadowsky, Case Western Reserve University, USA Chiara Thumiger, Kiel University, Germany AIMS & SCOPE Madness has strikingly ambiguous images in human history. All human societies seem to have a concept of madness, yet those concepts show extraordinary variance. Madness is widely seen, across time and cultures, as a medical problem, yet it often gestures towards other domains, including the religious, the moral, and the artistic. Madness impinges on the most personal and private sphere of human experience: how we understand the world, express ourselves about it, and share our mental, emotional and sensorial life with others. At the same time, madness is a public concern, often seeming to demand public response, at least by the immediate community, and often by the state. Madness is usually to some extent a disability, something that compromises functioning, yet is often also seen as a source of brilliance and inspiration. Madness is, virtually by definition, characterized by anomalous behavior, affect, and beliefs in any given context, and yet—partly because of this, and partly in spite of it— madness can be the most telling index of what a given society regards as normal or idealises as paradigm of functionality and health. In the ancient world, for example, reference to madness was used to qualify extraordinary characters, as in the famous case of the ‘melancholic’ as gifted individual, or of mania as associated to divine or poetic inspiration; unique experiences (religious, especially initiatory, but also creative and emotional); socio- political status (e.g., guilt deemed worthy of severe punishment, pollution); illness and bodily disturbance. -

CNS Spectrums

CNS Spectrums http://journals.cambridge.org/CNS Additional services for CNS Spectrums: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The following abstracts were presented as posters at the 2015 NEI Psychopharmacology Congress CNS Spectrums / Volume 21 / Issue 01 / February 2016, pp 77 - 121 DOI: 10.1017/S1092852915000905, Published online: 22 February 2016 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1092852915000905 How to cite this article: (2016). The following abstracts were presented as posters at the 2015 NEI Psychopharmacology Congress. CNS Spectrums, 21, pp 77-121 doi:10.1017/S1092852915000905 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CNS, IP address: 12.12.207.2 on 15 Mar 2016 CNS Spectrums (2016), 21,77–121. © Cambridge University Press 2016 doi:10.1017/S1092852915000905 ABSTRACTS The following abstracts were presented as posters at the 2015 NEI Psychopharmacology Congress Congratulations to the scientific poster winners of the 2015 NEI Psychopharmacology Congress! st 1 PLACE: Tardive Dyskinesia in the Era of Second Generation Antipsychotics: A Case Report and Literature Review (page 22) nd 2 PLACE: Comparing Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) and ECT for Treatment Resistant Depression in Elderly Population (page 37) rd 3 PLACE: The Complex Multimodal Management of First-Psychotic Episode in Patients with Morphometric Alteration in Hippocampal Formation (page 30) Violent Video Games – Physiological and variability, emotion, sleep quality, violent video game, Psychological Impact on Children and desensitization, aggressiveness”. Adolescents: Literature Review RESULTS: Literature so far shows an association between Sree Latha Krishna Jadapalle, MD1 and Monifa daily exposure to violent video games and number of Seawell, MD1 depressive and anxiety symptoms among pre-adolescent youth. -

Magic, Explanations, and Evil: the Origins and Design of Witches and Sorcerers

Magic, Explanations, and Evil The Origins and Design of Witches and Sorcerers Manvir Singh In nearly every documented society, people believe that some misfortunes are caused by malicious group mates using magic or supernatural powers. Here I report cross-cultural patterns in these beliefs and propose a theory to explain them. Using the newly created Mystical Harm Survey, I show that several conceptions of malicious mystical practitioners, including sorcerers (who use learned spells), possessors of the evil eye (who transmit injury through their stares and words), and witches (who possess superpowers, pose existential threats, and engage in morally abhorrent acts), recur around the world. I argue that these beliefs develop from three cultural selective processes: a selection for intuitive magic, a selection for plausible explanations of impactful misfortune, and a selection for demonizing myths that justify mistreatment. Separately, these selective schemes produce traditions as diverse as shamanism, conspiracy theories, and campaigns against heretics—but around the world, they jointly give rise to the odious and feared witch. I use the tripartite theory to explain the forms of beliefs in mystical harm and outline 10 predictions for how shifting conditions should affect those conceptions. Societally corrosive beliefs can persist when they are intuitively appealing or they serve some believers’ agendas. Online enhancements: supplemental material and tables. “I fear them more than anything else,”1 said Don Talayesva about witches. By then, the Hopi man suspected his grand- mother, grandfather, and in-laws of using dark magic against him. Introduction Humans in nearly every documented society believe that some illnesses and hardships are the work of envious or malig- Beliefs in witches and sorcerers are disturbing and calamitous. -

Faith Healer and Cultural Belief to Development of Psychopathology: a Case Report Iftikar Hussain1, Soumik Sengupta2, Sucheta Saha3

CASE REPORT Faith Healer and Cultural Belief to Development of Psychopathology: A Case Report Iftikar Hussain1, Soumik Sengupta2, Sucheta Saha3 ABSTRACT The presentation of mental illness and understanding of the patient’s experience with regard to psychopathology is quite unique and cannot be generalized due to the diverse etiological factors. In understanding and managing psychopathology, cultural knowledge plays a vital role. It has been seen that most of the interventions, in a similar fashion, need an understanding of historical roots in the specific cultural background and they also shape the psychotherapy models. The current case shows us the development of psychopathology with regard to cultural belief as well as discerning the symptom profile associated with it. Mr X, a 41-year-old gentleman from a rural area of Assam, presented with complaints about a “living thing” inhabiting his abdomen for the last 2 years and has been growing ever since. He claims that an enraged faith healer with incredible powers had done so to him. He was diagnosed with persistent delusional disorder at LGBRIMH and was managed with both pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. In nonpharmacological interventions, coping strategies and insight-oriented psychotherapy in context to his cultural beliefs were given. Significant improvement was seen after 2 months and at 3 months his socio-occupational functioning improved as well. Keywords: Cultural beliefs, Faith healer, Psychopathology. Indian Journal of Private Psychiatry (2019): 10.5005/jp-journals-10067-0026 INTRODUCTION 1–3Department of Psychiatry, Lokopriya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Understanding the dynamic interplay of cultural forces can be Institute of Mental Health, Tezpur, Assam, India an eye-opener to how people manifest symptoms, cope with Corresponding Author: Iftikar Hussain, Department of Psychiatry, psychological challenges, and how it aids in accurate diagnosis. -

Taxonomising Delusions: Content Or Aetiology?

Cognitive Neuropsychiatry ISSN: 1354-6805 (Print) 1464-0619 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/pcnp20 Taxonomising delusions: content or aetiology? Peter Clutton, Stephen Gadsby & Colin Klein To cite this article: Peter Clutton, Stephen Gadsby & Colin Klein (2017) Taxonomising delusions: content or aetiology?, Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 22:6, 508-527, DOI: 10.1080/13546805.2017.1404975 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2017.1404975 Published online: 20 Nov 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 37 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=pcnp20 Download by: [Macquarie University Library] Date: 04 December 2017, At: 12:37 COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHIATRY, 2017 VOL. 22, NO. 6, 508–527 https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2017.1404975 Taxonomising delusions: content or aetiology? Peter Clutton a, Stephen Gadsby b and Colin Klein a aDepartment of Philosophy, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia; bSchool of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Introduction: Many theoretical treatments assume (often implicitly) Received 2 April 2017 that delusions ought to be taxonomised by the content of aberrant Accepted 1 November 2017 beliefs. A theoretically sound, and comparatively under-explored, KEYWORDS alternative would split and combine delusions according to their Delusions; aetiology; underlying cognitive aetiology. taxonomy; belief; content Methods: We give a theoretical review of several cases, focusing on monothematic delusions of misidentification and on somatoparaphrenia. Results: We show that a purely content-based taxonomy is empirically problematic. It does not allow for projectability of discoveries across all members of delusions so delineated, and lumps together delusions that ought to be separated. -

Delusions in Early Intervention for Psychosis: Baseline

Delusions in Early Intervention for Psychosis: Baseline, Longitudinal and Cross-Cultural Contexts Ann-Catherine Lemonde, BA Department of Psychiatry McGill University November 2020 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of requirements of degree of Master’s of Science (M.Sc.) © Ann-Catherine Lemonde, 2020 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... 4 CONTRIBUTIONS OF AUTHORS ........................................................................................ 6 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 8 RÉSUMÉ ................................................................................................................................. 10 CHAPTER 1. THESIS INTRODUCTION: LITERATURE REVIEW AND RATIONALE ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.1 WHAT BELIEFS DO WE HOLD ABOUT DELUSIONS? ............................................................... 13 1.2 DELUSIONS IN THE EARLIEST PHASES OF PSYCHOSIS ........................................................... 16 1.3 WHAT CAN CONTEXT TEACH US ABOUT DELUSIONS?.......................................................... 19 1.4 OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................................................... 20 1.5 REFERENCES -

Do Psychologists Need to Know About Twerking? Why Staying Current with Adolescent Culture Is Critical to Effective Research and Practice

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 1, Issue 7, May 2014, PP 29-35 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) www.arcjournals.org Do Psychologists Need to Know About Twerking? Why Staying Current with Adolescent Culture is Critical to Effective Research and Practice Kelly-Ann Allen Meredith O’Connor Toorak College, Mount Eliza Institute of Positive Education The Melbourne Graduate School of Education Geelong Grammar School, Department of The University of Melbourne Paediatrics, The University of Melbourne [email protected] Murdoch Childrens Research Institute Royal Children’s Hospital Tracii Ryan Nerelie C. Freeman Department of Psychology School of Psychology & Psychiatry RMIT University Monash University Abstract: Through social media platforms (e.g., YouTube, Facebook), twerking became an online phenomenon in 2013 among young people in many Western countries, but has yet to appear in any scholarly discussions. This paper explores how well psychologists who are working with young people are ‘keeping up’ with a rapidly changing social landscape of popular youth culture, and whether it is important for them to do so. We argue that the hypermediacy of current adolescent culture poses significant challenges to the field of psychology in translating relevant, meaningful, and timely research and intervention. In identifying challenges currently experienced by psychologists that hamper efforts to maintain social cohesion with young people, we offer suggestions on how psychologists can address these challenges in research and practice. Keywords: social cohesion, psychology, adolescent mental health, popular culture, social media, twerking, SNS, youth With a focus on rapid exchanges of information across the globe, social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, YouTube, Twitter) have had a radical impact on adolescent development (e.g., identity formation; Caroll & Kirkpatrick, 2011; Davis, 2012; Ito et al. -

A Brief Review of Key Models in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For

Mini Review iMedPub Journals ACTA PSYCHOPATHOLOGICA 2017 www.imedpub.com ISSN 2469-6676 Vol.3 No. S2:84 DOI: 10.4172/2469-6676.100156 Peter Phiri*, Shanaya Rathod, A Brief Review of Key Models in Cognitive Hannah Carr and David Kingdon Behaviour Therapy for Psychosis Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK Abstract *Corresponding author: Peter Phiri Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) was originally developed as a comprehensive theory for treating depression. It has, however, since been extensively used to [email protected] treat a wide range of emotional and mental health problems and is now a plausible [email protected] treatment of choice for schizophrenia and associated psychotic symptoms. This review highlights the different models of CBT used for treating psychosis. These R&D Manager, Southern Health NHS models have varying background, theory and rationale. Overall, literature shows Foundation Trust, Tom Rudd Unit, that there are several models and approaches available but an underlying factor Moorgreen Hospital, Botley Road, West End shared by all is the centricity of collaborative empiricism and individual formulation Southampton, UK. of specific presentations, however this varies across models. These models begin to address the impact of culture on treatment of psychosis. That is, they begin to acknowledge that different cultures may have different interpretations of a Tel: 02380475112 psychotic presentation such as delusions. It is imperative that models such as those presented here begin to acknowledge cultural influences and take these into account during their formation. This will have an impact on the way psychosis Citation: Phiri P, Rathod S, Carr H, is treated using CBT.