A Brief Review of Key Models in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychopathology and Crime Causation: Insanity Or Excuse?

Fidei et Veritatis: The Liberty University Journal of Graduate Research Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 4 2016 Psychopathology and Crime Causation: Insanity or Excuse? Meagan Cline Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fidei_et_veritatis Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Cline, Meagan (2016) "Psychopathology and Crime Causation: Insanity or Excuse?," Fidei et Veritatis: The Liberty University Journal of Graduate Research: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fidei_et_veritatis/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fidei et Veritatis: The Liberty University Journal of Graduate Research by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cline: Psychopathology and Crime Causation: Insanity or Excuse? PSYCHOPATHOLOGY AND CRIME CAUSATION: INSANITY OR EXCUSE? By Meagan Cline One of the most controversial topics in the criminal justice industry is the "insanity defense" and its applicability or validity in prosecuting criminal cases. The purpose of this assignment is to identify and discuss psychopathology and crime causation in terms of mental illness, research, and the insanity defense. For this evaluation, information was gathered from scholarly research, textbooks, dictionaries, and published literature. These sources were then carefully reviewed and applied to the evaluation in a concise, yet informative, manner. This assignment also addresses some of the key terms in psychopathology and crime causation, including various theories, definitions, and less commonly known relevant factors influencing claims of mental instability or insanity. -

Televisionization: Enactments of TV Experiences in Novels from 1970 to 2010 Claudia Weber

Claudia Weber Claudia Televisionization Enactments of TV Experiences in Novels from 1970 to 2010 Claudia Weber Televisionization Claudia Weber pursued her doctoral studies both at Stock- holm University, Sweden and Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen, Germany. She is now employed at Technische Universität Darmstadt, Germany where she works in higher education didactics. ISBN 978-91-7447-979-9 Department of English Doctoral Thesis in English at Stockholm University, Sweden 2014 Televisionization: Enactments of TV Experiences in Novels from 1970 to 2010 Claudia Weber Televisionization Enactments of TV Experiences in Novels from 1970 to 2010 Claudia Weber © Claudia Weber, Stockholm University 2014 ISBN 978-91-7447-979-9 Printed in Sweden by Stockholm University Press, Stockholm 2014 Distributor: Department of English Abstract TV’s conquest of the American household in the period from the 1940s to the 1960s went hand in hand with critical discussions that revolved around the disastrous impact of television consumption on the viewer. To this day, watching television is connected with anxieties about the trivialization and banalization of society. At the same time, however, people appreciate it both as a source of information and entertainment. Television is therefore ‘both…and:’ entertainment and anxiety; distraction and allurement; compan- ionship and intrusion. When the role and position of television in culture is ambiguous, personal relations with, attitudes towards, and experiences of television are equally ambivalent, sometimes even contradictory, but the public and academic discourses on television tend to be partial. They focus on the negative impact of television consumption on the viewer, thereby neglecting whatever positive experiences one might associate with it. -

'The Assault on Mount B' by Rod Fee 1/129

‘The Assault on Mount B’ by Rod Fee 1/129 Rod Fee ID:0826790 ‘The Assault on Mount B: understanding the role of story in self-delusion in our personal histories.’ A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2015 Faculty: Applied Humanities School: Languages and Social Sciences Primary Supervisor: Dr Paul Mountfort Secondary Supervisor: Dr Maria O’Connor ‘The Assault on Mount B’ by Rod Fee 2/129 ATTESTATION OF AUTHORSHIP I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person (except where explicitly defined in the acknowledgements), nor material which to a substantial extent has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institution of higher learning. R H Fee ‘The Assault on Mount B’ by Rod Fee 3/129 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge the assistance of: 1. My two supervisors Dr Paul Mountfort and Dr Maria O’Connor, and Associate Professor Mark Jackson mentor supervisor, all of AUT University ‘The Assault on Mount B’ by Rod Fee 4/129 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS 1. All intellectual property including copyright, is retained by the candidate in the content of the candidate’s thesis. For the removal of doubt, publication by the candidate of this or any derivative work does not change the intellectual property rights of the candidate in relation to the thesis. 2. I confirm that my thesis does not contain plagiarised material or material for which the copyright or other intellectual property belongs to a third party. -

The Role of Psychopathology in the New Psychiatric Era

Psychopathology of the present The role of psychopathology in the new psychiatric era M. Luciano1, V. Del Vecchio1, G. Sampogna1, D. Sbordone1, A. Fiorillo1, D. Bhugra2 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of Naples SUN, Naples, Italy; 2 Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College, London, UK; World Psychiatric Association Summary based their practice over the last century. Re-examination The recent increase in mental health problems probably reflects should include the paradigm of mental disorders as nosologi- the fragmentation of social cohesion of modern society, with cal entities with the development of a new psychiatric nosol- changes in family composition, work and living habits, peer ogy, the concept of single disease entity, and a patient-cen- communication and virtual-based reality. Fragmentation can tered psychopathology, since actual descriptions are not able also be due to the rapid expansion of urban agglomerations, to catch the inner world and reality of patients with mental too often chaotic and unregulated, the increase of market illicit health problems. Some of these changes will be highlighted substances, the reduction of social networks and the increase of and discussed in this paper. social distance among people. As society changes, psychiatry has to adapt its role and target, moving from the treatment of Key words mental disorders to the management of mental health problems. This adaptation will require a re-examination of the paradigms Psychopathology • Biopsychosocial model • Nosology and classifica- of psychiatry on which mental healthcare professionals have tion of mental disorders • DSM-5 Introduction The fragmentation of social cohesion, which has de- termined changes in family composition, working and Since the institution of asylums, which had been func- living habits, problems in peer communication and the tioning for several centuries, introduction of antipsy- constitution of virtual-based realities, has brought many chotic drugs brought about a revolution. -

Learning from Delusions

OPINION Brian Martin nce or twice a year, I receive a call or Learning email from some- O one claiming to be under intensive tar- geted surveillance by the govern- from Delusions ment. They contact me because there’s a lot of material on my website about whistleblowing, and some about surveillance. I know governments carry out massive sur- veillance operations, for example collecting all sorts of electronic With others, the delusion is more ers, it just doesn’t make sense: there communications. However, these obvious, for example when they say is no obvious reason for them to be callers believe they have been spe- that a television program contains a an ongoing target of personalized cially selected as surveillance tar- message specifically designed and surveillance and harassment. gets, and sometimes for electronic inserted to affect their minds. or chemical bombardment too. My friend Steve Wright used The Truman Show Delusion One caller said he had written to work for the Omega Founda- With this background, I noticed a a political novel — unpublished — tion in Britain, which studies the book entitled Suspicious Minds. On and therefore the government was technology of repression, includ- the book jacket is the teaser “The monitoring his calls and following ing technologies for surveillance Truman Show delusion and other his every movement. He was very and electronic assault. He told me strange beliefs.” convincing. I suggested that he the Foundation would regularly The Truman Show is the name obtain evidence of the surveillance, hear from people who believed they of a film presenting the fictional but he always had some excuse, so were being electronically harassed. -

The Role of Psychopathology in Modern Psychiatry

JOURNAL OF PSYCHOPATHOLOGY Editorial 2018;24:111-112 A. Fiorillo1, B. Dell’Osso2, The role of psychopathology 3 4 G. Maina , A. Fagiolini in modern psychiatry 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Naples, Italy; 2 University of Milan, Department of Mental Health, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Psychiatry has been significantly influenced by the social, economic and Policlinico, Milan, Italy; Department of scientific changes that have occurred within the last few years. These in- Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Bipolar Disorders Clinic, Stanford University, CA, USA; fluences have evolved psychiatry into a modern medical specialty that is “Aldo Ravelli” Center for Neurotechnology increasingly knowledgeable about the structure and function of the brain, and Brain Therapeutic, University of Milan, mind (thoughts, feelings, and consciousness), behaviors and social re- Italy; 3 Rita Levi Montalcini Department of Neuroscience, University of Turin, Italy; lationships. Nonetheless, this knowledge has not uniformly spread and, 4 University of Siena, Department of Molecular in many institutions, psychiatric education and practice remain largely and Developmental Medicine, Siena, Italy based on knowledge developed over the last century. Over a century ago, the target of psychiatry was madness, and psychiatrists were called “alienists” 1. Along the years, the target has changed: for a number of years psychiatrists have been asked to treat mental disorders, and now the target has evolved to include the promotion of the mental health of the general population 2 3. In fact, some traditional illnesses have seemingly disappeared from clinical observation (e.g., organic brain disorder or in- volutional depression which were listed among the DSM-III diagnoses), while new forms of mental health problems have become of frequent ob- servation by psychiatrists. -

People with Dementia As Witnesses to Emotional Events

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: People with Dementia as Witnesses to Emotional Events Author: Aileen Wiglesworth, Ph.D., Laura Mosqueda, M.D. Document No.: 234132 Date Received: April 2011 Award Number: 2007-MU-MU-0002 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Laura Mosqueda, M.D. INSTITION: The Regents of the University of California, UC, Irvine, School of Medicine, Program in Geriatrics GRANT NUMBER: 2007-MU-MU-0002 TITLE OF PROJECT: People with Dementia as Witnesses to Emotional Events AUTHORS: Aileen Wiglesworth, PhD, Laura Mosqueda, MD DATE: December 23, 2009 Abstract Purpose: Demented elders are often the only witnesses to crimes against them, such as physical or financial elder abuse, yet they are disparaged and discounted as unreliable. Clinical experience with this population indicates that significant emotional experiences may be salient to people with dementia, and that certain behaviors and characteristics enhance their credibility as historians. -

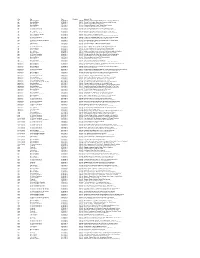

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 07/03/2013 0

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 07/03/2013 0:04:00 Doctors Recommend Baby Boomers Get Tested For Hepatitis C Age Morning Edition 07/05/2013 0:04:59 Seniors Flex Creative Muscles In Retirement Arts Colonies Age Tell Me More 07/08/2013 0:16:26 Winning Gold In Their Golden Years Age Morning Edition 07/11/2013 0:03:44 Chinatown 'Blessing Scams' Target Elderly Women Age Here & Now 07/18/2013 0:03:42 Cleveland Hosts National Senior Games Age All Things Considered 07/22/2013 0:07:20 Can Elderly Patients With Dementia Consent To Sex? Age All Things Considered 07/24/2013 0:05:37 Move Over Nursing Homes - There's Something Different Age Here & Now 07/25/2013 0:04:12 New Alzheimer's Research Could Lead To Treatments Age All Things Considered 07/26/2013 0:03:54 Age Hasn't Stopped This Man From Swimming And Winning Age Weekend Edition Sunday 07/28/2013 0:03:42 Athletic Glory At An Advanced Age Age Morning Edition 07/31/2013 0:03:55 Pickleball, Anyone? Senior Athletes Play New Games And Old Age All Things Considered 07/31/2013 0:04:45 For One Seniors Basketball Team, The Game Never Gets Old Age Here & Now 08/01/2013 0:16:27 Nursing Home Encourages Residents To Have Sex Age All Things Considered (Weekend) 08/03/2013 0:03:16 Worms' Bright Blue Death Could Shed Light On Human Aging Age Tell Me More 08/07/2013 0:01:35 Never Too Old To Take Gold Age Tell Me More 08/12/2013 0:19:38 Are We Ready For A Massive Aging Population? Age Morning Edition 08/20/2013 0:04:43 Older Farmers Seem To Be In No Hurry At All Age All Things Considered 08/23/2013 0:04:12 Summer Nights: Senior Softball In Huntington Beach, Calif. -

An Examination of Psychopathology and Daily Impairment in Adolescents with Social Anxiety Disorder

University of Central Florida STARS Faculty Bibliography 2010s Faculty Bibliography 1-1-2014 An Examination of Psychopathology and Daily Impairment in Adolescents with Social Anxiety Disorder Franklin Mesa University of Central Florida Deborah C. Beidel University of Central Florida Brian E. Bunnel University of Central Florida Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/facultybib2010 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Bibliography at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Bibliography 2010s by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Mesa, Franklin; Beidel, Deborah C.; and Bunnel, Brian E., "An Examination of Psychopathology and Daily Impairment in Adolescents with Social Anxiety Disorder" (2014). Faculty Bibliography 2010s. 5834. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/facultybib2010/5834 An Examination of Psychopathology and Daily Impairment in Adolescents with Social Anxiety Disorder Franklin Mesa*, Deborah C. Beidel, Brian E. Bunnell University of Central Florida, Orlando, Florida, United States of America Abstract Although social anxiety disorder (SAD) is most often diagnosed during adolescence, few investigations have examined the clinical presentation and daily functional impairment of this disorder exclusively in adolescents. Prior studies have demonstrated that some clinical features of SAD in adolescents are unique relative to younger children with the condition. Furthermore, quality of sleep, a robust predictor of anxiety problems and daily stress, has not been examined in socially anxious adolescents. In this investigation, social behavior and sleep were closely examined in adolescents with SAD (n = 16) and normal control adolescents (NC; n = 14). -

Dan Klein Psych a 338; 632-7859

Dan Klein Psych A 338; 632-7859 PSY 596 - PSYCHOPATHOLOGY II: Externalizing and Psychotic Disorders Spring, 2018 The goal of this class is to familiarize you with current concepts and research on child, adolescent, and adult psychopathology. The class meets on Thursdays from 1:00-2:50 in Psych B 316. This is the second semester of a two-semester sequence. During the previous semester, we covered conceptual models and methods and the internalizing disorders (mood and anxiety disorders). This semester, we will deal primarily with externalizing and non-mood psychotic disorders. Class meetings will consist of lectures designed to provide a broad overview of the topic for that class and discussion. Typically, we will cover diagnosis and classification, epidemiology, course, and the genetic, neurobiological, and psychosocial factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis and maintenance of the disorder. We will not discuss treatment, as that is the focus of other courses. The required readings, listed below, will generally consist of 5-6 papers per week. Please make the time to read each of the assigned articles. Some of the readings will be difficult, so don't be discouraged if you have to struggle with them. Focus on the main questions, findings, and implications of the papers, and don’t worry if you cannot grasp the more technical details. Readings that address diversity issues are indicated by a + symbol. Almost all of the readings are available in the campus library electronic journal collections; I have placed a * in front of the exceptions. You may find it helpful to read the relevant sections from the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV), although I am not assigning it. -

Major Depressive Disorder in Children and Adolescents: Etiologies, Course, Gender Differences, and Treatments

VISTAS Online VISTAS Online is an innovative publication produced for the American Counseling Association by Dr. Garry R. Walz and Dr. Jeanne C. Bleuer of Counseling Outfitters, LLC. Its purpose is to provide a means of capturing the ideas, information and experiences generated by the annual ACA Conference and selected ACA Division Conferences. Papers on a program or practice that has been validated through research or experience may also be submitted. This digital collection of peer-reviewed articles is authored by counselors, for counselors. VISTAS Online contains the full text of over 500 proprietary counseling articles published from 2004 to present. VISTAS articles and ACA Digests are located in the ACA Online Library. To access the ACA Online Library, go to http://www.counseling.org/ and scroll down to the LIBRARY tab on the left of the homepage. n Under the Start Your Search Now box, you may search by author, title and key words. n The ACA Online Library is a member’s only benefit. You can join today via the web: counseling.org and via the phone: 800-347-6647 x222. Vistas™ is commissioned by and is property of the American Counseling Association, 5999 Stevenson Avenue, Alexandria, VA 22304. No part of Vistas™ may be reproduced without express permission of the American Counseling Association. All rights reserved. Join ACA at: http://www.counseling.org/ Suggested APA style reference information can be found at http://www.counseling.org/library/ Article 2 Major Depressive Disorder in Children and Adolescents: Etiologies, Course, Gender Differences, and Treatments Paper based on a program presented at the 48th South Carolina Counseling Association Conference, February 24, 2012, Myrtle Beach, SC. -

A CULTURAL HISTORY of MADNESS - Bloomsbury

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF MADNESS - Bloomsbury GENERAL EDITORS Jonathan Sadowsky, Case Western Reserve University, USA Chiara Thumiger, Kiel University, Germany AIMS & SCOPE Madness has strikingly ambiguous images in human history. All human societies seem to have a concept of madness, yet those concepts show extraordinary variance. Madness is widely seen, across time and cultures, as a medical problem, yet it often gestures towards other domains, including the religious, the moral, and the artistic. Madness impinges on the most personal and private sphere of human experience: how we understand the world, express ourselves about it, and share our mental, emotional and sensorial life with others. At the same time, madness is a public concern, often seeming to demand public response, at least by the immediate community, and often by the state. Madness is usually to some extent a disability, something that compromises functioning, yet is often also seen as a source of brilliance and inspiration. Madness is, virtually by definition, characterized by anomalous behavior, affect, and beliefs in any given context, and yet—partly because of this, and partly in spite of it— madness can be the most telling index of what a given society regards as normal or idealises as paradigm of functionality and health. In the ancient world, for example, reference to madness was used to qualify extraordinary characters, as in the famous case of the ‘melancholic’ as gifted individual, or of mania as associated to divine or poetic inspiration; unique experiences (religious, especially initiatory, but also creative and emotional); socio- political status (e.g., guilt deemed worthy of severe punishment, pollution); illness and bodily disturbance.