The Italian Twins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Courier Gazette : December 22, 1885

T he Courier-Gazette. ROCKLAND OA7.ETTK KSTABI ISHED 1R40. ( (TWO nnl.I.ARR A VKAIl IN ADTANCRl ROCKLAND COURIER ERTARMSHRD 1074. | <fln $lress is tbe 3irtbtincbean jfeber that Jfiobes tbe tfdlorlb at if too Dollars a (bar (SINUI.E COI-1K8 PRICK FIVK CKMT8. V o l . 4.—N e w S e r i e s . ROCKLAND, MAINE, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 22, 1885. N u m b e r 49. T h e coij ri er-gazette VAGRANT CHRISTMAS MUSINGS. that served as a dressing-room screen, Aldor THE CHRISTMAS POEM. “ There’s life for you. Nothing mewling us lilt iis with Ids skunk, anil when wilh great about that,” said the sporting editor, trium illdlcitlty we recovered from our confusion E oitfo by W. o. Fri.i.r.R, .Ir. W hat a good “Wliat in the matter ?” asked the managing phantly. tlmcChristinasls! and entered upon our song, he lifted up Ids editor. “ Where arc the liells in this poem ?’’ Inquired voire in such long-sustained and powerful the exchange editor ns he laid down bin It was n North Carolina man who mliireiRcd Oh, come now, The youngest young man on tlie staffhnd for Imitations of n eow, that we quite lost our scissors nnd rested the corns on his thumb. hi» petition to lltu Majesty President Cleve don't be so crnl>- some minutes liecn roving the dirty walls of the presenco of mind, and in a moment of rash “ You don’t seem to snv anything about tlie land. lie ought to have the oflico. -

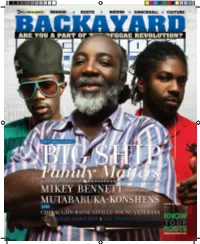

Untitled Will Be out in Di Near Near Future Tracks on the Matisyahu Album, I Did Something with Like Inna Week Time

BACKAYARD DEEM TEaM Chief Editor Amilcar Lewis Creative/Art Director Noel-Andrew Bennett Managing Editor Madeleine Moulton (US) Production Managers Clayton James (US) Noel Sutherland Contributing Editors Jim Sewastynowicz (US) Phillip Lobban 3G Editor Matt Sarrel Designer/Photo Advisor Andre Morgan (JA) Fashion Editor Cheridah Ashley (JA) Assistant Fashion Editor Serchen Morris Stylist Judy Bennett Florida Correspondents Sanjay Scott Leroy Whilby, Noel Sutherland Contributing Photographers Tone, Andre Morgan, Pam Fraser Contributing Writers MusicPhill, Headline Entertainment, Jim Sewastynowicz, Matt Sarrel Caribbean Ad Sales Audrey Lewis US Ad Sales EL US Promotions Anna Sumilat Madsol-Desar Distribution Novelty Manufacturing OJ36 Records, LMH Ltd. PR Director Audrey Lewis (JA) Online Sean Bennett (Webmaster) [email protected] [email protected] JAMAICA 9C, 67 Constant Spring Rd. Kingston 10, Jamaica W.I. (876)384-4078;(876)364-1398;fax(876)960-6445 email: [email protected] UNITED STATES Brooklyn, NY, 11236, USA e-mail: [email protected] YEAH I SAID IT LOST AND FOUND It seems that every time our country makes one positive step forward, we take a million negative steps backward (and for a country with about three million people living in it, that's a lot of steps we are all taking). International media and the millions of eyes around the world don't care if it's just that one bad apple. We are all being judged by the actions of a handful of individuals, whether it's the politician trying to hide his/her indiscretions, to the hustler that harasses the visitors to our shores. It all affects our future. -

Tarrus Riley “I Have to Surprise You

MAGAZINE #18 - April 2012 Busy Signal Clinton Fearon Chantelle Ernandez Truckback Records Fashion Records Pablo Moses Kayla Bliss Sugar Minott Jah Sun Reggae Month Man Free Tarrus Riley “I have to surprise you. The minute I stop surprising you we have a problem” 1/ NEWS 102 EDITORIAL by Erik Magni 2/ INTERVIEWS • Chantelle Ernandez 16 Michael Rose in Portland • Clinton Fearon 22 • Fashion Records 30 104 • Pablo Moses 36 • Truckback Records 42 • Busy Signal 48 • Kayla Bliss 54 Sizzla in Hasparren SUMMARY • Jah Sun 58 • Tarrus Riley 62 106 3/ REVIEWS • Ital Horns Meets Bush Chemists - History, Mystery, Destiny... 68 • Clinton Fearon - Heart and Soul 69 Ras Daniel Ray, Tu Shung • 149 Records #1 70 Peng and Friends in Paris • Sizzla In Gambia 70 Is unplugged the next big thing in reggae? 108 • The Bristol Reggae Explosion 3: The 80s Part 2 71 • Man Free 72 In 1989 MTV aired the first episode of the series MTV Unplugged, a TV show • Tetrack - Unfinished Business 73 where popular artists made new versions of their own more familiar electron- • Jah Golden Throne 74 Anthony Joseph, Horace ic material using only acoustic instrumentation. It became a huge success • Ras Daniel Ray and Tu Shung Peng - Ray Of Light 75 Andy and Raggasonic at and artists and groups such as Eric Clapton, Paul McCartney and Nirvana per- • Peter Spence - I’ll Fly Away 76 Chorus Festival 2012 formed on the show, and about 30 unplugged albums were also released. • Busy Signal - Reggae Music Again 77 • Rod Taylor, Bob Wasa and Positive Roots Band - Original Roots 78 • Cos I’m Black Riddim 79 110 Doing acoustic versions of already recorded electronic material has also been • Tarrus Riley - Mecoustic 80 popular in reggae music. -

Image to PDF Conversion Tools

Complete Radio Programs By The Hour, A Page To A Day Long Wave 5 Short Wave °RADIO Cents News Spots the Copy it Pictures MICR'PlIONE $1.50 Year N olume Ill. No. 35 \X TEK ENDING SEPTLIBkli 1931 Published Week y E This and That E. Communications Commission Denies Ç .. By Morris Hastings THE PROGRAM schedule for Attempting `New Deal Censorship' next season, as announced in a recent issue of The MIaRo- PHONE, shows clearly the strength and, more clearly still, the weak- Biggest Football Schedule Political ness of radio. Its strength lies in in its ability Fate oritism to foster char- In History Of The Networks acters such as A m o s 'n' l.earfin Lady Is Charged ANDY, thc Best Games Sore Throat GOLD BERGS, 1 By The MICROPHONE'S Simi-i4 t h e person- Washington Correspondent ages of the Of Season to Helps to Win "Roses a n Steady drum -fire of charges that D r u m s" be Broadcast An Audition the Communications Commission s k e tches, was preparing to clamp down cen- How it feels to become a na- BILLY BATCH - sorship on the radio was expected to tional radio star overnight was ELOR - all of At least 18 ipajor college foot- evoke a statement from the Commis- whom, it is ball games will be broadcast over told to The MICROPHONE in an sion definitely indicating what it in- thought ap- the Columbia network and the exclusive interview with ROWENE tends to do. parent, many outstanding games of the season WILLIAMS, winner of the recent The Commission has no authority will also be heard over the NBC Columbia nationwide audition in law Mr. -

New Square Dance Vol. 24, No. 4 (Apr. 1969)

APRIL 1969 SOURRE ■ RNCE THE EDITORS' PAGE 4 Webster's Dictionary defines "vaca- tion" as "a period of absence from work, for recreation." Look at the 1. Dance as much as you like, but word "recreation" a s-creation, a take a break if you feel pressure to time for renewal, for ise in the rat- keep going. (Vacations are times to race, for more relaxing )ursuits than get away from pressure and tension). during the working year. 2. Visit spots of interest in the area As spring rolls around after the long where you are-- natural as well as winter, a young man's fancy turns to commercial. thoughts of love, but many a dancer's 3. Be sure to include time for partici- fancy turns to square dancing vaca- pation in available activities, golf, swim tions-- one day festivals, weekends, ming, tennis-- maybe even bridge. weeks, fortnights. You'll find all 4. Make new friends and acquain- lengths, sites, and kinds listed in this tances -- good conversation and fellow- special issue. Whether your taste runs ship are relaxing at any time. to a plush hotel, a rustic resort or a do- 5. Tell your favorite partner once a it-yourself campsite, there's a vacation day that you are enjoying yourself and that will suit it. like being with him (her). We'd like to offer several tips for get- ting the most out of your 1969 vacation And when you have a ball on a S/D with the reminder that you can enjoy a vacation, be sure to tell the director square dance vacation without total ab- you read about it in SQUARE DANCE- sorption in the hobby. -

Achy Breaky Song (3:19)

"Weird Al" Yankovic - Achy Breaky Song (3:19) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Addicted to Spuds (3:41) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Amish Paradise (3:18) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Bohemian Polka (3:38) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Eat It (3:11) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Fat (3:34) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Gump (2:09) "Weird Al" Yankovic - I Love Rocky Road (2:32) "Weird Al" Yankovic - I Remember Larry (3:37) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Livin' In The Fridge (3:21) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Phony Calls (3:17) "Weird Al" Yankovic - Syndicated Inc. (3:53) "Weird Al" Yankovic - The Night Santa Went Crazy (3:56) "Weird Al" Yankovic - The Rye Or The Kaiser (Theme from Rocky XIII) (3:30) 'NSync Featuring Nelly - Girlfriend (Neptunes Remix) (4:43) 'Til Tuesday - Coming Up Close (4:31) 'til Tuesday - Voices Carry (4:13) 'til Tuesday - What About Love (3:55) *NSYNC - Crazy For You (3:37) *NSYNC - God Must Have Spent A Little More Time On You (4:35) *NSYNC - Here We Go (3:31) *NSYNC - I Just Wanna Be With You (4:00) *NSYNC - I Want You Back (3:18) *NSYNC - Tearin' Up My Heart (3:26) *NSYNC - You Got It (3:29) 1 - Fox Trot Mixer (3:30) 1 - Rumba (3:13) 1 - Waltz (2:40) 1 Giant Leap Feat. Robbie Williams & Maxi Jazz - My Culture (3:55) 10 - Fox Trot (3:10) 10 - Fox Trot (3:14) 10 - Waltz Mixer (2:27) 10 cc - The Things We Do For Love (3:18) 10 Years - Novacaine (2:44) 10 Years - Through The Iris (3:25) 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days (3:35) 101 Strings Orchestra - 2001 A Space Odyssey Fanfare (1:14) 10cc - I'm Not In Love (3:47) 11 - Waltz Mixer (2:50) 11 - WC (3:43) 11 - West Coast Swing (3:09) 12 - V. -

American Square Dance Vol. 41, No. 2

AMERICAN SQURRE DANCE A LOW COST WAY TO • • COMPLETE THE SQUARE DANCE LOOK MATCHING ACCESSORIES Bola Buckle Collar Tip. Scarf Slide Peedaat Earrimp Mother of Pearl 9.00 10.00 8.00 5.00 6.00 6.00 Black Onyx 11.00 12.00 8.00 7.00 9.00 8.00 Blue Onyx 11.00 12.00 9.00 8.00 9.00 8.00 • Tiger Eye 16.00 18.00 12.00 9.00 15.00 10.00 Abalone 9.00 10.00 8.00 5.00 6.00 6.00 Goldstone 11.00 12.00 8.00 8.00 9.00 8.00 "POUNDED GOLD" or "POUNDED SILVER" Square Dame Figure 2 Pleas Sou • oa% $24.00 per set HOLLY HILLS ROSES A Bouquet set for Square and Round Dancers Buckle - Bola - Collar Tips Ladies Matching Pendant $10.00 $24.00 set These delightful sets come in 3 styles: BLUE ROSE- RED ROSE - YELLOW ROSE ... AND......FOR YOUR PARTNER Goldtone Setting Available le a . ) axt. Matching PendantsS5.00 Buckles Fit Western Matching Earrings $11.00 Snapron Belts up to Is" Gemstone list on request WHISTLES - $4.00 Member - NASRDS "TRACK 2" or "LOAD THE BOAT" (Holly Hills Specials) • RAYON BOLA CORDS -- SI.50 ea. 1411, 611, BLACK. BROWN. WHITE, NAVY, 2-G2 Holly Lane BEIGE, KELLY GREEN, FOREST P.O. Box 233 GREEN. ROYAL BLUE, BLUE. GOLD. Tuckerton, N.J. 08087 TURQUOISE. SILVER, RED, GRAY. (609) 296-1205 MAROON OR GARNET. Add $1.50 for postage 4-PLY LEATHER BOLA CORDS and handling • 36" Regular -- $6.00 New Jersey residents add 6% 42- Long - S12.00 State Sales Tan DOMED BEAD OR BEAD Check 21i" White Tips -- $6.00 VISA - MasterCard • AMERICAN [3] SQURRE ORNCE FEBRUARY 1986 VOLUME 41, No. -

American Square Dance Vol. 40, No. 8

AMERICAN SQUARE DRNCE AUGUST 1985 Amos] WO Ships Cary 111ao • HOLLY HILLS ROSES SQUARE UP WITH THESE ALWAYS POPULAR A Bouquet set for AUTHENTIC GEMSTONES Square and Round Dancers 0 Buckle Bola Collar Tips BOLA BUCKLE SCARF SLOE COLLAR TIP MOTHER OF PEARL 900 1000 500 El 130 BLACK ONYX 11 00 12 00 700 BOO BLUE ONYX 11 00 12 00 800 10 00 .•-, TIGER EVE 18 00 18 00 900 12 00 $24.00 These delightful sets Come in four styles: per set SPECIAL • AS 0 BLUE ROSE RED ROSE - YELLOW ROSE 2 Piece Set Dedtai 92 00 Roses on Black Piece Set • Deduct 94 00 4 Piece Set • Deduct 58 00 AND FOR YOUR PARTNER Matching Pendants 55.00 AND OON'T FORGET YOUR PARTNER? Matching Earrings 58.00 PENDANTS 40 30 25 . 18 18 . 13 FARB, "POUNDED GOLD" or "POUNDED SILVER MOTHER OF PEARL 600 500 400 6 _Square Dancer Figure Set BLACK ONYX 9 00 700 600 BLUE ONYX B00 R00 500 s ee S24.00 set TIGER EYE 15 00 900 6 (X) Ladies Matching 'TRACK 2" WHISTLES 41:440 Pendant $10.00 S4.00 each a Goldtone Setting Asailable Check • VISA - MasterCard Buckles Fit Western 1,16 Add $1.50 for postage Snap-on Belts l's 2-G2 Holly Lane 11= and handling P.O. Box 233 O Gemstone list on request Tuckerton, N.J. 08087 • Nara Jersey residents add 6' i `_A Member - NSARDS (609) 296-1205 ,64;;4 State Sales Tax....„ ° , t •rIt zollini • ‘....-..... 0 1009,so,cesov, sTnn and CATHIE BURDICH 0 07,9. -

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマットジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 79.5 Predictions BCR047

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマットジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 79.5 Predictions BCR047 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 2,090 https://tower.jp/item/4797162 1773 リターン・オブ・ザ・ニュー RRCRB90103 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 2,300 https://tower.jp/item/2525329 1773 Return Of The New (HITS PRICE) RRCRF120117 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 933 https://tower.jp/item/3102523 2562 The New Today MBIPI5546 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 2,100 https://tower.jp/item/3729257 2562 フィーバー DOUBT1CDJP CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 2,000 https://tower.jp/item/2872650 43670 Love/Life Changes 10410844 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 2,390 https://tower.jp/item/1623907 *Groovy workshop. Emotional Groovin' -Best Hits Mix- mixed by *Groovy workshop. SMCD53 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 1,890 https://tower.jp/item/4624195 100 Proof (Aged in Soul) エイジド・イン・ソウル VSCD023 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 2,800 https://tower.jp/item/244446 100% Pure Poison カミング・ライト・アット・ユー(PS) PCD24428 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 2,400 https://tower.jp/item/3968463 16FLIP P-VINE & Groove-Diggers Presents MIXCHAMBR : Selected & MixedPTRCD24 by 16FLIP <タワーレコード限定>CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 2,000 https://tower.jp/item/3931525 2 Chainz B.O.A.T.S. II Me Time(INTL) 3751328 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 1,890 https://tower.jp/item/3293591 2 Chainz Collegrove(INTL) 4785537 CD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 1,890 https://tower.jp/item/4234390 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) 2-PAC 4-EVER COBY91233 DVD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 3,800 https://tower.jp/item/2084155 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) Live at the house of blues(BRD) ERBRD5051 DVD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 1,890 https://tower.jp/item/4644444 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) Final 24 : His Final Hours MVD4990D DVD SOUL/CLUB/RAP 1,890 https://tower.jp/item/2782460 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) Conspiracy -

Breaking Ground 2017 BOUNDARIES

Sharon Slilaty | Where Water Becomes Ice This edition of Breaking Ground is the collaboration of the Spring 2017 English 175 Class Professor Christopher Origer Paul Archer Abigail Clain Haley Marie Lipps Miranda Moses Alex Plesnar Careline Ramirez Jasmine Thorson As well as the many bright minds of the artists and writers represented within breaking ground 2017 BOUNDARIES SUNY Broome Community College Literary Magazine Binghamton, New York Please direct all correspondence to: Professor Christopher Origer, Editor Breaking Ground Department of English SUNY Broome Community College P.O. Box 1017 Binghamton, NY 13902 email: [email protected] Copyright © 2017 SUNY Broome Literary Magazine Breaking Ground Printed by Bob Carr 2.0 Printing, Binghamton, New York All rights to the works contained here are retained by the individual writers and artists represented in this issue of Breaking Ground. No part may be reproduced without their consent. Acknowledgements Extreme gratitude goes out to Rose Pero and Amanda Truin as assistant editors for all the late nights and numerous hours it took to get this edition of the magazine to completion; also to Josh Lewis for his sharp eyes in proofreading during the spring break; to Michael Bodnar, once again, for his helpful technical assistance; to Abigail Clain and Patrick Mulderig for final work on the cover; to Sandra Cohn and Maureen Schwarz for the technical wizardry in the final hours of production; and to Ciara Cable for sound InDesign advice before going to press. Thanks also to all the wonderful students of the Spring 2017 ENG175 class, who pitched in with enthusiasm in the several weeks of readings it took to sift through the numerous submissions. -

New Release Guide

ada–music.com @ada_music NEW RELEASE GUIDE August 21 August 28 ORDERS DUE JULY 17 ORDERS DUE JULY 24 2020 ISSUE 18 August 21 ORDERS DUE JULY 17 ERASURE The Neon Street Date: 8/21/20 Mute are pleased to announce the release of Erasure’s Depeche Mode, Pet Shop Boys, (Andy Bell and Vince Clarke) 18th studio album, The Neon, FOR FANS OF: Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark to be released August 21 on limited edition neon orange vinyl, standard black vinyl, limited edition CD, and digital Neon Orange LP: 724596995730 platforms. SLRP: 22.98 File Under: Electronic The Neon is a place that lives in the imagination. It could Box Lot: 25 LP Non-Returnable be a night club, a shop, a city, a cafe, a country, a bedroom, NOT FOR EXPORT a restaurant, any place at all. It’s a place of possibility in warm, glowing light and this is music that takes you there. LP: 724596995716 SLRP: 22.98 Written and produced by Erasure, the album’s initial File Under: Electronic sessions saw Vince and Andy reunite to work on the Box Lot: 25 follow up to 2017’s World Be Gone with a fresh optimism LP Non-Returnable NOT FOR EXPORT and energy, in part born from their own recent personal CD: 724596995723 projects. Vince goes on to explain, “Our music is always a SLRP: 14.98 reflection of how we’re feeling. Andy was in a good place File Under: Electronic spiritually, and so was I – really good places in our minds. Box Lot: 30 You can hear that.” NOT FOR EXPORT Taking inspiration from pop music through the decades, Digital UPC: 724596995754 from bands Andy loved as a child through to the present day, he explains, “It was about refreshing my love – TRACKLISTING: hopefully our love – of great pop. -

Downbeat.Com December 2015 U.K. £3.50

DECEMBER 2015 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson,